INCLUSION IN THE RECORDING STUDIO?

EXAMINING POPULAR SONGS

USC ANNENBERG INCLUSION INITIATIVE

@Inclusionists

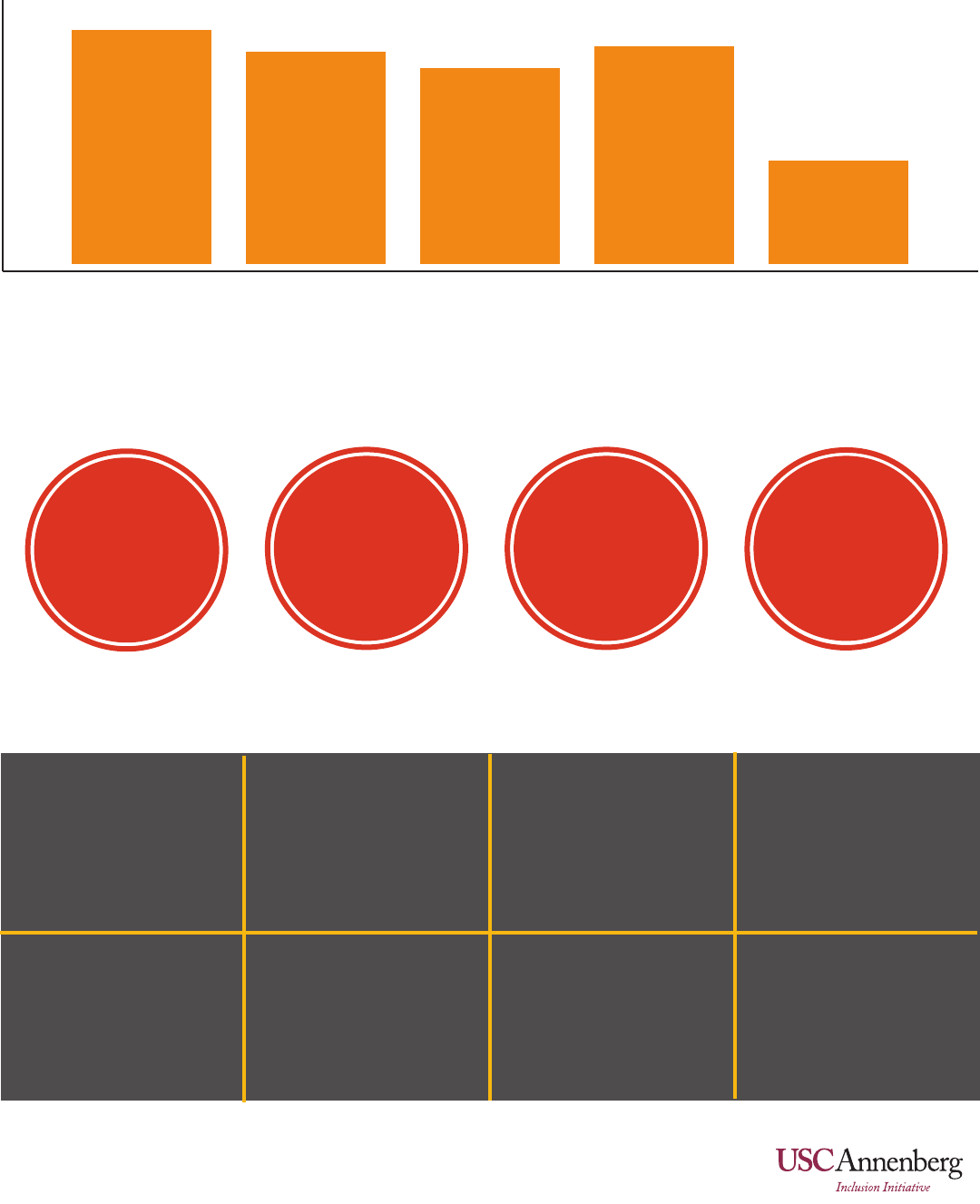

FEMALES ARE MISSING IN POPULAR MUSIC

22.7

21.9

20.9

25.1

28.1

16.8

Prevalence of Female Artists across 700 Songs, in percentages

RATIO OF MALES TO FEMALES

3.6:1

TOTAL NUMBER

OF ARTISTS

1,455

© 2019 DR. STACY L. SMITH

17.1

FOR FEMALES, MUSIC IS A SOLO ACTIVITY

Across 700 songs, percentage of females out of...

31.5

INDIVIDUAL

ARTISTS

DUOS BANDS

21.7

ALL

ARTISTS

4.6 7.5

47

to

1

THE RATIO OF MALE TO FEMALE PRODUCERS

ACROSS 400 POPULAR SONGS IS

FEMALES ARE PUSHED ASIDE AS PRODUCERS

‘12 ‘13 ‘14 ‘15 ‘16 ‘17 ‘18

0

30

60

© 2019 DR. STACY L. SMITH

FEMALES

MALES

WRITTEN OFF: FEW FEMALES WORK AS SONGWRITERS

Songwriter gender by year...

2012 2014 2017

89%

11%

87.3%

12.7%

87.7%

12.3%

TOTAL

87.8%

12.2%

2013 20162015 2018

88.3%

11.7%

86.3%

13.7%

86.7%

13.3%

88.5%

11.5%

38.4

30.7

35.1

48.7 48.4

51.9

55.6

44%

OF ARTISTS WERE

PEOPLE OF COLOR

ACROSS SONGS

FROM

2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018

Percentage of artists of color by year...

VOICES HEARD: ARTISTS OF COLOR ACROSS SONGS

Percentage of women across three creative roles

WOMEN ARE MISSING IN THE MUSIC INDUSTRY

.%

ARE

ARTISTS

.%

ARE

SONGWRITERS

.%

ARE

PRODUCERS

© 2019 DR. STACY L. SMITH

2017

2015

TOTAL

1.8%

98.2%

1.8%

98.2%

2.1%

97.9%

CREATIVE CONSTRAINTS: FEW FEMALE PRODUCERS WORK IN MUSIC

2012

2.4%

97.6%

2018

2.3%

97.7%

8714

PRODUCERS WERE

WOMEN OF COLOR

OUT OF

WOMEN OF COLOR ARE INVISIBLE AS PRODUCERS

20

35

50

65

80

40%

33%

73%

52%

Percentage of underrepresented male and female artists by year...

MEN AND WOMEN OF COLOR CLIMB THE CHARTS

Female

Male

‘12 ‘13 ‘14 ‘15 ‘16 ‘17 ‘18

0

25

50

75

100

© 2019 DR. STACY L. SMITH

CREDITS & DEFICITS: MALES OUTPACE FEMALES IN SONGWRITING

Martin Sandberg (Max Martin)

Aubrey Graham (Drake)

Henry Walter (Cirkut)

Lukasz Gottwald (Dr. Luke)

Savan Kotecha

Johan Schuster (Shellback)

Dijon McFarlane (DJ Mustard)

Michael Williams (Mike WILL Made-it)

THE TOP MALE

WRITER HAS

39

Onika Maraj (Nicki Minaj)

Katheryn Hudson (Katy Perry)

Adele Adkins

Sia Furler

Selena Gomez

Robyn Fenty (Rihanna)

Belcalis Almanzar (Cardi B)

Taylor Swift

Benjamin Levin (Benny Blanco)

39

33

24

22

21

19

18

15

14

18

14

12

9

8

8

8

7

Leading male and female songwriters by number of credits...

CREDITS

THE TOP FEMALE

WRITER HAS

18

CREDITS

ACROSS 700 POPULAR

SONGS FROM

2012-2018

The top 10 male songwriters are responsible for 23% of the 700 most popular songs from 2012 to 2018.

Top Male Songwriters

# of

credits

Top Female Songwriters

# of

credits

10.4%

OF GRAMMY

®

NOMINEES

FROM 2013-2019

WERE FEMALE.

89.6% WERE MALE.

THE GENDER GAP AT THE GRAMMYS

®

IS REAL

Percentage of Female Nominees by Category, 2013-2019

93.4 79.491.8

Record of

the Year

Album of

the Year

Song of

the Year

Best New

Artist

58.9 97.4

Producer

of the Year

6.6 20.68.2 41.1 2.6

Female

Adam Levine 14

Brittany Hazzard (Starrah) 8

Male

© 2019 DR. STACY L. SMITH

BARRIERS FACING FEMALES IN MUSIC

25%

WERE THE

ONLY WOMAN

28%

WERE

DISMISSED

20%

NOTED DRUGS

& ALCOHOL

39%

WERE

OBJECTIFIED

WHAT HAPPENS TO WOMEN IN THE RECORDING STUDIO?

Experiences of 75 songwriters and producers

STRATEGIC SOLUTIONS TO FOSTER SYSTEMIC CHANGE

SHE

IS THE

MUSIC

P&E

INCLUSION

INITIATIVE

SPOTIFY EQL

RESIDENCY

PROGRAM

SET TARGET

INCLUSION

GOALS

FOR THE

RECORD

COLLECTIVE

MENTORSHIP

PROGRAMS

INCLUSION

RIDER

COLLECTIVE

ACTION

43%

39%

36%

40%

19%

Skills

Discounted

Stereotyped

& Sexualized

Male-Dominated

Industry

Navigating

the Industry

Financial

Instability

Experiences of 75 songwriters and producers

Inclusion in the Recording Studio?

Gender & Race/Ethnicity of Artists, Songwriters, & Producers

across 700 Popular Songs from 2012-2018

Dr. Stacy L. Smith, Marc Choueiti, Dr. Katherine Pieper, Hannah Clark, Ariana Case, & Sylvia Villanueva

Annenberg Inclusion Initiative

USC

with assistance from Angel Choi, Kevin Yao and Adaeze Ene

The aim of this study was to examine the quantitative and qualitative realities of working in the recording

studio. Quantitatively, we assessed gender and race/ethnicity of artists, songwriters, and producers on

the Hot 100 year-end Billboard Charts from 2012-2018. Grammy® nominees over the same time frame

were also reviewed, focusing on demographics within the following categories: record of the year, album

of the year, song of the year, best new artist, and producer of the year. Qualitatively, the investigation

takes a deeper dive into barriers and opportunities women experience in the recording studio. We

conducted 75 in-depth interviews with female songwriters and producers to gather information on the

impediments they face in music as well as potential solutions to create change.

Artists, Songwriters & Producers on Billboard Charts

Artists

. A full 1,455 artists were credited across the sample of 700 songs. In 2018, 82.9% of artists on the

year end charts were male and 17.1% were female. This computes into a gender ratio of 4.8 male artists

to every one female artist. 2018 (17.1%) was not different from 2017 (16.8%) in terms of female

participation. These two years featured the lowest percentages of females on the Hot 100 list across the

seven years evaluated.

In 2018, females only represented 26.2% of credited solo artists which was not different than 2017 but

was 9.6 percentage points lower than 2012. Not one woman in a duo or band appeared on the Hot 100

chart of 2018. 2018 was substantially lower than 2012 for female participation in duos and bands.

For males, the range of credits was from 1-33. Drake held the top spot with 33 solo credits across the

sample time frame, followed by Justin Bieber (13 songs) and Chris Brown (13 songs). The range of credits

for females was a bit narrower (1-21), with Rihanna the top performer followed by Nicki Minaj (20 songs)

and Taylor Swift (12 songs).

Across 1,455 artists, 56% were white and 44% were from underrepresented racial/ethnic groups. A

majority of artists (55.6%) on the 2018 charts were people of color which is well above U.S. Census

(39.3%). The percentage of artists of color in 2018 was not different from 2017, but the proportion was

meaningfully higher (>5 percentage points) than 2012 (+17.2) and every other year in the sample.

In 2018, the percentage of women of color on the charts was at a seven year high. A full 73% of female

artists were from underrepresented racial/ethnic groups in 2018 which is 23 percentage points higher

than 2017 and 40 percentage points higher than 2012. For underrepresented males, 2017 (52%) and

2018 (52%) did not differ. However, the percentage of male artists of color on the charts in 2018 was

significantly higher (12 percentage points) than 2012 (40%).

Songwriters.

A total of 3,330 songwriters were credited on the seven-year sample. A full 87.7% were

males and 12.3% were females. This calculates into a gender ratio of 7.1 male songwriters to every one

female. No changes in the percentage of female songwriters were observed between 2017 (11.5%) and

2018 (12.2%), nor did either of these years vary meaningfully from 2012 (11%).

Of the 411 female songwriters assessed, 43.3% were from underrepresented racial/ethnic groups and

56.7% were white. However, marked variation was observed over time. 59.4% of female songwriters

were underrepresented in 2018 which was higher than 2017 (53.5%). Only 29.8% of female songwriters

were women of color in 2012, a percentage substantially lower than 2018.

Differences emerged by gender among the top performing songwriters. The top male songwriter had

over two times as many credits (Max Martin, 39 credits) as the top female songwriter on the year-end

charts (Nicki Minaj, 18 credits). The top 10 male songwriters wrote or co-wrote just under a quarter

(23%) of all songs in the sample.

Out of 633 songs, 48 songs (7.6%) were written by at least one female songwriter who did not work with

a female artist on the song. A total of 90 songs (14.2%) featured at least one female artist and at least one

female songwriter. This is a 6.6 percentage point gain. Female artists may be the key to increasing

women’s access and opportunity to write in the music industry. This is imperative, as females face an

epidemic of invisibility penning songs. Of the 633 songs, 360 or 57% lacked the presence of a female

writer. In stark contrast, only 3 or <1% lacked any male songwriters.

Producers

. Across 400 songs, 871 producers, co producers and vocal producers were credited. 97.9% of

producers were male and only 2.1% were female. There has been no change over the four years

evaluated, with a gender ratio of 47.4 male producers to every one female producer.

We removed the 14 songs that repeated across the charts in the time frame examined (4 years), bringing

the sample to 386. After this, the total number of female producers reduced to 15 individual women and

17 credits. Eleven of these producers were white and 4 were from underrepresented racial/ethnic

groups. Only two women worked twice as producers across the songs evaluated.

Grammys

. 1,064 individuals received a Grammy Award® nomination in 5 select categories from 2013 to

2019. A full 89.6% were male and 10.4% were female, a gender ratio of 8.6 males to every one female.

The percentage of female nominees in 2019 was significantly higher than 2018 and 2013. Despite this,

2018 was not different than 2015 or 2016 in the percentage of women nominated.

While males were the majority of nominees in each category, females were most likely to be nominated

for Best New Artist, followed by Song of the Year. In the Record and Album of the Year categories, fewer

than 10% of nominees were women. For the first time in the seven years analyzed, a woman (Linda Perry)

was nominated for Producer of the Year.

For female nominees, race/ethnicity was analyzed. Overall, 36.9% of female nominees were women of

color. The largest number of underrepresented females received nominations for Album of the Year,

followed by Record of the Year and Best New Artist—the latter category grew by 16.1 percentage points

from last year’s total.

Qualitative Trends

Interviews with 75 female songwriters and producers were conducted to examine the impediments

facing women in the music industry. Spontaneous and prompted answers were analyzed for recurring

themes that pointed to the existence of a career barrier. Below, major findings as well as solutions are

presented.

General Career Barriers.

40% percent of interviewees stated that they face difficulty navigating the

industry, including breaking into the business, making connections, and getting into different rooms.

Second, the financial instability associated with a music career was mentioned by 19% of women. They

described the lack of royalties available to songwriters and producers, the changing nature of the industry

due to streaming services, and the difficulties associated with supporting oneself on the income

generated from songwriting or producing.

Women’s Skills and Abilities are Discounted.

A full 43% of interviewees stated that two main issues

confronted them as songwriters and producers. First, they were dismissed or not taken seriously—their

abilities, competence, and knowledge in the role of songwriter or producer were doubted or were

undercut by their colleagues. A second and related issue was that they had to prove their competence to

individuals who might work with them.

In a separate follow-up question, 92% of women said their leadership or vision had been resisted by a

colleague. Women reported that they were ignored or discounted (43%) such that their contributions

were either not seen as important or not recognized. Nearly one-third (29%) stated that they were

demeaned, or that others argued, embarrassed them or undermined their input. A further 19% said that

women taking on leadership threatened men, while 16% stated that stereotyping about their gender was

used to dismiss their work or their abilities.

Sexualized & Stereotyped.

39% of participants provided spontaneous answers that illuminated that

women’s careers are inextricably tied to expectations about their gender and sexual availability. Women

reported being sexualized (21%), which included being the subject of innuendo, undesired attention,

propositioned, valued for their appearance, and even an awareness or fear of being personally unsafe in

work situations.

Interviewees also answered a question that specifically asked whether any aspect of the environment of

the recording studio had ever made them feel uncomfortable or uneasy. More than three-quarters (83%)

of participants said that they or other women experienced discomfort in the studio. 39% stated that they

had been objectified, and 25% pointed to being the lone female or one of few women in environments

populated by males. Third, 28% were uncomfortable due to having their contributions, knowledge, or

expertise dismissed, or due to facing hostile language from others. Fourth, 20% of interviewees noted

that drugs, alcohol, and sexualized women were part of studio culture. Finally, 11% of respondents

provided other reasons for their uneasiness.

One-quarter (25%) of interviewees spontaneously stated that gender stereotypes guided others’

expectations about their behavior, treatment, or opportunities they were given. The responses in this

category illuminate that simply being a woman in music can serve as a barrier to career success. Across

interview responses, 12% of participants also gave unprompted responses indicating that the qualities

associated with producing were associated with males—and that the job itself was not viewed as

something women could do. In other words, when individuals think producer, they think male.

Male-Dominated Industry.

36% of participants gave unprompted answers regarding a barrier that

occurred as the result of being a statistical minority in the music business. A full 29.3% (n=22) of

interviewees in this category stated that the music industry was male-dominated or functioned as the

proverbial ‘boy’s club.’ This category also included responses (12%, n=9) who stated that there were few

females in songwriting and production, including few female role models, and the handful of responses

(4%, n=3) indicating that women were competitive with each other.

Solutions for Change

The report also highlights several opportunities for creating industry change. These include creating

environments where women are welcome and generating opportunities for women to use their skills and

talents. Other solutions suggested are to ensure that role models and mentorships are available to

women, and for the industry to commit to considering and hiring more women. The report also

illuminates the work of different organizations or initiatives that seek to address the barriers identified in

the study. The goals and activities of She Is The Music, Spotify’s EQL Residency Program, For The Record

Collective, and others are discussed.

Inclusion in the Recording Studio?

Gender & Race/Ethnicity of Artists, Songwriters, & Producers

across 700 Popular Songs from 2012-2018

Dr. Stacy L. Smith, Marc Choueiti, Dr. Katherine Pieper, Hannah Clark, Ariana Case, & Sylvia Villanueva

Annenberg Inclusion Initiative

USC

with assistance from Angel Choi, Kevin Yao and Adaeze Ene

The aim of this study was to examine the quantitative and qualitative realities of working in the recording

studio. Quantitatively, we assessed gender and race/ethnicity of artists, songwriters, and producers on

the Hot 100 year-end Billboard Charts from 2012-2018. Longitudinally, a total of 5,656 credits were

scrutinized for their demographic information. The Grammy® nominees over the same time frame were

also reviewed, focusing on demographics within the following categories: record of the year, album of the

year, song of the year, best new artist, and producer of the year.

Qualitatively, the investigation takes a deeper dive into barriers and opportunities women experience in

the recording studio. We conducted 75 in-depth interviews with female songwriters and producers to

gather information on the impediments they face in music as well as potential solutions to create change.

The interviews were conducted during the summer and fall of 2018 and serve to illuminate the lived

experiences of female artisans in this employment space.

Below, the report features four major sections. First, we overview the current state of the recording

studio by gender and underrepresented racial/ethnic status of artists. Second, we focus on the

Grammys® and representation among nominees. Third, we offer thematic results of our qualitative

interviews with female songwriters and producers regarding their work in the recording studio. The

report concludes with a summary of the major findings and specific solutions for change.

Quantitative Assessment of Artists

Credited artists and songwriters were examined for gender and race/ethnicity across the 700 top songs

from 2012-2018. A subset of this sample (400 songs) was evaluated for producer demographic attributes:

2012, 2015, 2017, and 2018. In this section, we first present the results for 2018 and then provide

comparisons to 2017 and 2012 (on select measures). Only ±5 percentage point differences were

discussed to avoid making noise about meaningless deviations (1-2 percentage points). For information

on our methodology and decision making, please see the footnotes of last year's report.

Gender

. A full 1,455 artists were credited across the sample of 700 songs.

1

In 2018 (see Table 1), 82.9% of

artists on the year end charts were male (n=179) and 17.1% were female (n=37). This computes into a

gender ratio of 4.8 male artists to every one female artist. 2018 (17.1%) was not different from 2017

(16.8%) in terms of female participation. These two years featured the lowest percentages of females on

the Hot 100 list across the seven years evaluated. Such figures are surprising, given that females

comprise 50% of the U.S. population

as well as

roughly half of music buyers and streamers in the

audience.

2

Table 1

Artist Gender by Year

Artist Gender

2012

2013

2014

2015

2016

2017

2018

Total

Males

77.3%

(n=153)

78.1%

(n=168)

79.1%

(n=178)

74.9%

(n=146)

71.9%

(n=138)

83.2%

(n=178)

82.9%

(n=179)

78.3%

(n=1,140)

Females

22.7%

(n=45)

21.9%

(n=47)

20.9%

(n=47)

25.1%

(n=49)

28.1%

(n=54)

16.8%

(n=36)

17.1%

(n=37)

21.7%

(n=315)

Gender Ratio

3.4 to 1

3.6 to 1

3.8 to 1

3 to 1

2.5 to 1

4.9 to 1

4.8 to 1

3.6 to 1

Besides gender, we also evaluated

genre

and

performer type

. Focusing first on genre, every song in the

sample was labeled using the iTunes distinction. Then, the genre label was applied across all the

performers and artists on each song.

3

As such, the results are presented at the performer level and not

the song level. Table 2 illuminates that males worked primarily in Pop (35.4%), Hip-Hop/Rap (28.7%) and

Alternative (15.8%). The majority of females worked in Pop (61.6%) and a much lower percentage in Hip-

Hop/Rap (15.2%).

Table 2

Song Genre by Artist Gender

Genre

Males

Females

Gender Ratio

Pop

35.4%

(n=404)

61.6%

(n=194)

2.1 to 1

Hip-Hop/Rap

28.7%

(n=327)

15.2%

(n=48)

6.8 to 1

Alternative

15.8%

(n=180)

5.7%

(n=18)

10 to 1

Country

6.4%

(n=73)

6.7%

(n=21)

3.5 to 1

R&B/Soul

5.4%

(n=62)

2.9%

(n=9)

6.9 to 1

Dance/Electronic

8.3%

(n=94)

7.9%

(n=25)

3.8 to 1

While these findings reflect within gender breakdowns, it is important to look at the chart

share

within

each genre. We did this by looking at the proportion of performing credits held by males and females per

song category. By examining the gender ratio column, it is obvious that male artists dominated every

employment opportunity with ratios ranging from 2 to 1 in Pop (low) to 10 to 1 in Alternative (high).

The

type of credit

was evaluated next. Artists were grouped into individual performers, duos, and bands.

Over half of all artists were individual performers (59.7%, n=869), followed by members of bands (32.9%,

n=478) and duos (7.4%, n=108). Featuring artists on songs were included in this breakdown, within

specific type.

4

In 2018, females only represented 26.2% of credited solo artists which was not different

than 2017 but was 9.6 percentage points lower than 2012 (see Table 3). Not one woman in a duo or band

appeared on the Hot 100 chart of 2018. 2018 does not differ meaningfully from 2017 for females

working in groups. However, 2018 was substantially lower than 2012 for female participation in duos and

bands. Because so few females were featured in duos or bands across the seven-year time line, these

findings should be interpreted with caution.

Table 3

Percentage of Female Artists by Type of Credit

Type of Artist

2012

2013

2014

2015

2016

2017

2018

Total

Individual

35.8%

(n=39)

33.3%

(n=37)

35.8%

(n=43)

30.8%

(n=41)

35.2%

(n=43)

25.6%

(n=34)

26.2%

(n=37)

31.5%

(n=274)

Duo

16.7%

(n=1)

10%

(n=2)

0

10%

(n=1)

0

4.5%

(n=1)

0

4.6%

(n=5)

Band

6%

(n=5)

9.5%

(n=8)

4.6%

(n=4)

13.5%

(n=7)

22.9%

(n=11)

1.7%

(n=1)

0

7.5%

(n=36)

Note: Bands refer to any group featuring three or more performers under one moniker. For the percentage of male

artists by year and credit type, subtract the cell percentage from 100. Featuring credits were included within specific

credit type. Columns do not add to 100%.

While the previous analyses focused on all artists, we now turn our attention to how often the

same

performers

appeared across the seven-year sample. To this end, we first had to remove any duplicate

songs that appeared more than once in the sample time frame (n=67). Then, we reduced each performer

to a single line of data and tallied up how many times s/he appeared with a solo or featuring credit. The

total sample of 1,455 artists was reduced by 64% (n=782 repeat appearances). The total number of

individual or unique artists across seven years of Hot 100 charts was 529. Now, we look to see who is

routinely working by gender within credit type (i.e., individual, duo, band).

The results for solo artists can be found in Table 4. Despite being fewer in number, female artists seem to

be punching at the same weight as male artists with one, three, four, and six or more credits across the

sample. The only meaningful differences emerged with males more likely to have two credits than their

female counterparts whereas the opposite trend (females>males) emerged for five credits.

Table 4

Number of Songs by Artists with Solo Credits by Gender

#

of Songs

Male Artists

Female Artists

Total

# of

Artists

%

# of

Artists

%

# of

Artists

%

1

132

57.6%

47

55.9%

179

57.2%

2

36

15.7%

8

9.5%

44

14.1%

3

19

8.3%

9

10.7%

28

8.9%

4

14

6.1%

4

4.8%

18

5.7%

5

4

1.7%

7

8.3%

11

3.5%

≥6

24

10.5%

9

10.7%

33

10.5%

Total

229

100%

84

100%

313

100%

Note: For presentational purposes, the range of 6 or more songs was grouped into one level. Individual artists'

credits were ascertained using their name and/or pseudonym on solo or featuring credits.

However, the range of credits differed by gender. For males, the range of credits was from 1-33 (see

Table 5). Drake held the top spot with 33 solo credits, followed by Justin Bieber (13 songs) and Chris

Brown (13 songs). The range of credits for females was a bit narrower (1-21), with Rihanna the top

performer followed by Nicki Minaj (20 songs) and Taylor Swift (12 songs).

Table 5

Top Individual Artists of Songs by Gender

Top

Males

#

of Songs

Top

Females

#

of Songs

Drake

33

Rihanna

21

Justin Bieber

13

Nicki Minaj

20

Chris Brown

13

Taylor Swift

12

Calvin Harris

11

Ariana Grande

11

Kendrick Lamar

11

Selena Gomez

9

The Weeknd

10

Katy Perry

8

Bruno Mars

9

Cardi B

8

Future

9

Adele

8

Turning to duos, a total of 25 performing pairs were credited across the sample. Twenty one duos were

male only (84%), 12% (n=3) featured a male and female pair and only 1 (4%, i.e., Icona Pop) contained

two female performers. The top performing duo had 7 song credits across seven years (Florida Georgia

Line), followed by The Chainsmokers (5 songs) and Macklemore and Ryan Lewis (5 songs). There were 45

bands in sample, 71.1% (n=32) featured all males, 24.4% involved males and females (n=11), and only two

(4.4%, Fifth Harmony, Pistol Annies) were all females. The top performing bands were Maroon 5 (13

songs), Imagine Dragons and Migos (8 songs each), and One Direction (6 songs).

Taken together, the results of this section reveal pronounced gender differences on the Hot 100 year-

end charts from 2012-2018. While females comprised under a third of individual performers, their

presence in duos and bands was in the single digits. Further, no female within a duo or band appeared

across the 100 top songs of 2018. We now turn our attention to examine another demographic

characteristic on the Billboard year end charts, race/ethnicity.

Race/Ethnicity

. Every artist also was coded as underrepresented or not (white).

5

Across 1,455 artists, 56%

(n=815) were white and 44% (n=640) were from underrepresented racial/ethnic groups. As shown in

Table 6, a majority of artists (55.6%) on the 2018 charts were underrepresented which is well above U.S.

Census (39.3%).

6

The percentage in 2018 was not different from 2017, but the proportion was

meaningfully higher (>5 percentage points) than 2012 (+17.2) and every other year in the sample.

Table 6

Underrepresented Artists by Year

Performers

2012

2013

2014

2015

2016

2017

2018

Total

Not

Underrepresented

61.6%

(n=122)

69.3%

(n=149)

64.9%

(n=146)

51.3%

(n=100)

51.6%

(n=99)

48.1%

(n=103)

44.4%

(n=96)

56%

(n=815)

Underrepresented

38.4%

(n=76)

30.7%

(n=66)

35.1%

(n=79)

48.7%

(n=95)

48.4%

(n=93)

51.9%

(n=111)

55.6%

(n=120)

44%

(n=640)

Total

198

215

225

195

192

214

216

1,455

Similar to gender, we examined how underrepresented status (no, yes) varied with

gender

,

genre

, and

credit type

(individual, duos, bands). The intersection of

gender

and underrepresented status is shown in

Figure 1. In 2018, the percentage of underrepresented females was at a seven year high. A full 73% of

female artists were from underrepresented racial/ethnic groups in 2018 which is 23 percentage points

higher than 2017 and 40 percentage points higher than 2012. For underrepresented males, 2017 (52%)

and 2018 (52%) did not differ. However, the percentage of underrepresented male artists on the charts in

2018 was significantly higher (12 percentage points) than 2012 (40%).

Figure 1

Underrepresented Male & Female Artists Over Time

Pivoting to

genre

, Table 7 reveals that song type is related to artist underrepresented status.

Underrepresented artists were more likely to be credited with Hip-Hop/Rap or R&B/Soul songs than their

Caucasian peers. White artists were more likely to have songs from Pop, Alternative, Country, and

Dance/Electronic than underrepresented artists.

In addition to gender and genre, we were interested in whether

performer type

was associated with

underrepresented status. As shown in Table 8, the vast majority of solo artists were from

underrepresented racial/ethnic groups in 2018 (70.2%). This percentage does not differ from 2017 but is

substantially higher than 2012 (54.1%). A very different story emerged with duos, with only 20% of

performers underrepresented in 2018 which was significantly lower than 2017 (27.3%) and 2012 (66.7%).

Given small cell sizes, these results should be interpreted cautiously. The percentage of UR band

members was 29.2% in 2018, which was not different than 2017 (30.5%) but higher than 2012 (15.7%).

40%

30%

38%

52%

46%

52%

52%

33%

32%

23%

39%

54%

50%

73%

0%

20%

40%

60%

80%

2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018

UR Males

UR Females

Table 7

Song Genre by Underrepresented Artists

Genre

Underrepresented

Artists

Not Underrepresented

Artists

Pop

32.7%

(n=209)

47.7%

(n=389)

Hip-Hop/Rap

50.2%

(n=321)

6.6%

(n=54)

Alternative

1.4%

(n=9)

23.2%

(n=189)

Country

<1%

(n=3)

11.2%

(n=91)

R&B/Soul

10%

(n=64)

<1%

(n=7)

Dance/Electronic

5.3%

(n=34)

10.4%

(n=85)

Table 8

Percentage of Underrepresented Artists by Credit Type

Credit Type

2012

2013

2014

2015

2016

2017

2018

Total

UR Solo

Artists

54.1%

(n=59)

51.3%

(n=57)

52.5%

(n=63)

56.4%

(n=75)

60.7%

(n=74)

65.4%

(n=87)

70.2%

(n=99)

59.1%

(n=514)

UR Artists in

Duos

66.7%

(n=4)

15%

(n=3)

38.9%

(n=7)

70%

(n=7)

18.2%

(n=4)

27.3%

(n=6)

20%

(n=2)

30.6%

(n=33)

UR Artists in

Bands

15.7%

(n=13)

7.1%

(n=6)

10.3%

(n=9)

25%

(n=13)

31.3%

(n=15)

30.5%

(n=18)

29.2%

(n=19)

19.5%

(n=93)

Note: For the percentage of white artists by year and credit type, subtract the cell percentage from 100. Featuring

credits were included within specific credit type.

Table 9

Number of Songs by Underrepresented Artists with Solo Credits

#

of Songs

UR Artists

Not UR Artists

Total

# of

Artists

%

# of

Artists

%

# of

Artists

%

1

96

54.5%

83

60.5%

179

57.2%

2

26

14.8%

18

13.1%

44

14.1%

3

17

9.7%

11

8%

28

8.9%

4

12

6.8%

6

4.4%

18

5.7%

5

7

4%

4

2.9%

11

3.5%

≥6

18

10.2%

15

10.9%

33

10.5%

Total

176

100%

137

100%

313

100%

Note:

For presentational purposes, the range of 6 or more songs was grouped into one level. Individual artists'

credits were ascertained using their name and/or pseudonym on solo or featuring credits.

To look at unique or solo performers, we applied the same sift to the data as noted above with gender. A

total of 313 unique artists worked across 700 songs (see Table 9). One difference emerged in Table 9,

with white artists (60.5%) more likely to have a single credit across the sample than underrepresented

artists (54.5%). Just under a sixth (14.1%) of performers had two credits in the sample, 18.2% had three

to five credits. One-tenth of the artists had six or more credits across seven years.

Table 10

Top Individual Artists by Underrepresented Status

Top

UR Artists

#

of Songs

Top

Not UR Artists

#

of Songs

Drake

33

Justin Bieber

13

Rihanna

21

Taylor Swift

12

Nicki Minaj

20

Ariana Grande

11

Chris Brown

13

Calvin Harris

11

Kendrick Lamar

11

Adele

8

The Weeknd

10

Katy Perry

8

Ed Sheeran

8

The top performing solo artists by underrepresented status can be found in Table 10. The top under-

represented artist was Drake, with 33 songs in the sample time frame. Drake had two and a half times

more solo credits than the top white artist (Justin Bieber, 13 songs). Further, two of the top three

underrepresented artists were women (Rihanna, 21 songs, Nicki Minaj, 20 songs) who also had more hits

than any white artist on the list.

Besides solo credits, we also explored underrepresented artists’ participation in duos and bands. Of the

25 performing pairs, 9 or 36% were underrepresented and 3 (12%) featured underrepresented and white

artists. Just over half of all duos were white (52%). The top performing underrepresented duos were Rae

Sremmurd (4 songs) and LMFAO (2 songs) whereas the top performing white duos were Florida Georgia

Line (7 songs), The Chainsmokers (5 songs), and Macklemore and Ryan Lewis (5 songs).

Of the 45 bands, only 8.9% (n=4) featured all underrepresented members, 14 featured (31.1%) a mix of

underrepresented and white performers and 27 (60%) were white only. The top performers were Maroon

5 (13 songs), Migos (8 songs), and Imagine Dragons (8 songs).

In total, the findings reveal that underrepresented artists dominated a great deal of the Billboard charts.

In 2018 alone, underrepresented performers accounted for over half of the artists on the Hot 100 year-

end chart. Women of color comprised over 70% of female artists in 2018. The top three performers

across the entire study were each from underrepresented racial/ethnic groups. Unlike other forms of

entertainment (e.g., TV, film), underrepresented performers are thriving in the music business.

Songwriters & Producers

Songwriters and Producers were also evaluated demographically. Here, we assessed gender for all

content creators and underrepresented status for females only. For songwriters, the full seven-year

sample was evaluated whereas only four years were assessed for producers. Given that so few females

have access and opportunity to produce, a smaller sample was sufficient to establish trends.

Songwriters

. A total of 3,330 songwriters were credited on the seven-year sample.

7

A full 87.7%

(n=2,919) were males and 12.3% (n=411) were females (see Table 11). This calculates into a gender ratio

of 7.1 male songwriters to every one female. No changes in the percentage of females were observed

between 2017 (11.5%) and 2018 (12.2%), nor do either of these years vary meaningfully from 2012

(11%).

Table 11

Songwriter Gender by Year

Writer Gender

2012

2013

2014

2015

2016

2017

2018

Total

Males

89%

(n=380)

88.3%

(n=355)

87.3%

(n=404)

86.3%

(n=415)

86.7%

(n=424)

88.5%

(n=445)

87.8%

(n=416)

87.7%

(n=2,919)

Females

11%

(n=47)

11.7%

(n=47)

12.7%

(n=59)

13.7%

(n=66)

13.3%

(n=65)

11.5%

(n=58)

12.2%

(n=69)

12.3%

(n=411)

Gender Ratio

8.1 to 1

7.5 to 1

6.8 to 1

6.3 to 1

6.5 to 1

7.7 to 1

7.2 to 1

7.1 to 1

Note: The gender of three writers was not ascertainable. Another 8 writers on songs were listed as "unknown."

These eleven were not included in the above analysis.

Three additional measures were evaluated for female songwriters. The first was

race/ethnicity

. Each

female songwriter was evaluated for underrepresented status (no, yes). Of the 411 females assessed,

43.3% were from underrepresented racial/ethnic groups and 56.7% were white. However, marked

variation was observed over time. As shown in Table 12, 59.4% of female songwriters were

underrepresented in 2018 which was higher than 2017 (53.5%). Only 29.8% of female songwriters were

women of color in 2012, a percentage substantially lower than 2018.

Table 12

Percentage of Underrepresented Female Songwriters

2012

2013

2014

2015

2016

2017

2018

Total

% UR Females

29.8%

36.2%

32.2%

39.4%

46.1%

53.5%

59.4%

43.3%

Total #

47

47

59

66

65

58

69

411

Note: The percentage of white female songwriters can be obtained by subtracting a particular

cell from 100%.

Besides underrepresented status, we also assessed the

genre

of female songwriters. The majority of

female songwriters were in Pop (58.6%) followed by Hip-Hop/Rap (17.8%) and Dance/Electric (9.5%). Few

were writing lyrics and melodies in the R&B/Soul (5.8%), Alternative (4.4%), and Country (3.9%) space.

Similar to performers, we also scrutinized writing credits by gender (see Table 13). There were no

meaningful differences (±5 percentage points) in the number of credits for males and female songwriters

in the sample evaluated. Thus, female songwriters were punching at the same weight as their male peers

but were afforded fewer opportunities.

Table 13

Number of Songs by Songwriter Gender

#

of Songs

Male Songwriters

Female Songwriters

Total

# of

Writers

%

# of

Writers

%

# of

Writers

%

1

894

68%

131

70.8%

1,025

68.3%

2

190

14.5%

19

10.3%

209

13.9%

3

75

5.7%

7

3.8%

82

5.5%

4

32

2.4%

8

4.3%

40

2.7%

5

32

2.4%

8

4.3%

40

2.7%

≥6

92

7%

12

6.5%

104

6.9%

Total

1,315

100%

185

100%

1,500

100%

Note: Percentages were calculated within gender. The range of 6 or more was collapsed for presentational

purposes.

Where differences emerged by gender was among top performing songwriters (see Table 14). As shown,

the top male songwriter had over two times as many credits (Max Martin) as the top female songwriter

on the year-end charts (Nicki Minaj). The top 10 male songwriters wrote or co-wrote just under a quarter

(23%) of all songs in the sample.

Table 14

Top Individual Songwriters by Gender

Top Male Songwriters

# of

Songs

Top Female Songwriters

# of

Songs

Martin Sandberg (Max Martin)

39

Onika Maraj (Nicki Minaj)

18

Aubrey Graham (Drake)

33

Robyn Fenty (Rihanna)

14

Benjamin Levin (Benny Blanco)

24

Taylor Swift

12

Henry Walter (Cirkut)

22

Katheryn Hudson (Katy Perry)

9

Lukasz Gottwald (Dr. Luke)

21

Adele Adkins

8

Savan Kotecha

19

Sia Furler

8

Johan Schuster (Shellback)

18

Belcalis Almanzar (Cardi B)

8

Dijon McFarlane (DJ Mustard)

15

Brittany Hazzard (Starrah)

8

Michael Williams II (Mike WILL Made-it)

14

Selena Gomez

7

Adam Levine

14

The final question addressed in this section is this: do female artists support and work with women

songwriters? To answer this query, we only looked at non-duplicating songs in the sample to avoid

double counting. Thus, our sample size reduced to 633. Then, we examined each song for the gender of

the artist and the songwriter. 21.3% (n=135) of the songs in the sample were by female singer-

songwriters with no additional non-performing female writers. These women do not provide employment

opportunities for other women and predominantly worked with male writers and other male artists.

Out of 633 songs, 48 songs (7.6%) were written by at least one female songwriter who did not work with

a female artist on the song. A total of 90 songs (14.2%) featured at least one female artist and at least one

female songwriter. This is a 6.6 percentage point gain. Female artists may be the key to increasing

women’s access and opportunity to write in the music industry. This is imperative, as females face an

epidemic of invisibility penning songs. Of the 633 songs, 360 or 57% lacked the presence of a female

writer. In stark contrast, only 3 or <1% lacked any male songwriters.

Producers

. For producers, our investigation only focused on a subset of songs. Here, we examined the top

400 songs of 2012, 2015, 2017, and 2018. Across 400 songs, 871 producers, co producers and vocal

producers were credited.

8

An individual receiving multiple producing credits on a song was only counted

once. A total of 853 or 97.9% of producers were male and only 2.1% were female (n=18). The yearly

breakdown is revealed in Table 15. There has been no change over the four years evaluated, with a

gender ratio of 47.4 males to every one female.

Table 15

Producer Gender by Year

Gender

2012

2015

2017

2018

Total

Males

97.6% (n=200)

98.2% (n=217)

98.2% (n=221)

97.7% (n=215)

97.9% (n=853)

Females

2.4% (n=5)

1.8% (n=4)

1.8% (n=4)

2.3% (n=5)

2.1% (n=18)

Ratio

40 to 1

54.3 to 1

55.3 to 1

43 to 1

47.4 to 1

We removed the 14 songs that repeated across the charts in the time frame examined, bringing the

sample to 386. After this, the total number of female producers reduced to 15 individual women and 17

credits. Eleven of these producers were white and 4 were from underrepresented racial/ethnic groups.

Only two women worked twice as producers across the songs evaluated.

The results for songwriters and producers point to the continued exclusion of women from these

positions. The percentages in 2018 reflect that there has been no change in hiring practices related to

women behind the scenes in these roles. As songwriters, women of color were 59.4% of the females

writing popular music in 2018, and 43.3% of female songwriters overall. Female producers of color,

however, do not fare as well. Only 4 women of color have producing credits across the 400 songs

analyzed. In the next section, we move to exploring differences by gender and race/ethnicity in critical

acclaim.

Grammy Awards®: 2013-2019

The goal of this section is to understand how critical and industry honors vary by gender and to update

our previous analysis on the Grammy® nominations. Seven years (2013-2019) of selected categories of

Grammy® nominations were analyzed.

9

These were: Record of the Year, Album of the Year, Song of the

Year, Best New Artist, and Producer of the Year. We identified every individual who received a

nomination in these categories from the 55

th

to the 61

st

Grammy Awards®, including the individual

members of groups. The results below are discussed by year and by category. The final analysis overviews

gender differences in the frequency of nominations.

1,064 individuals received a Grammy Award® nomination in the select categories from 2013 to 2019. A

full 89.6% were male and 10.4% were female, a gender ratio of 8.6 males to every one female. Table 15

reveals that the percentage of female nominees in 2019 was significantly higher than 2018 and 2013.

Despite this, 2018 was not different than 2015 or 2016 in the percentage of women nominated. One

explanation for this increase is the expansion of nominees in several categories, allowing for a numerical

increase in both women and men over prior years.

Table 15

Grammy® Nominations by Gender and Year

2013

2014

2015

2016

2017

2018

2019

Total

Males

92.1%

(n=105)

91.8%

(n=156)

85.9%

(n=134)

88.5%

(n=138)

93.6%

(n=190)

92%

(n=92)

83.6%

(n=138)

89.6%

(n=953)

Females

7.9%

(n=9)

8.2%

(n=14)

14.1%

(n=22)

11.5%

(n=18)

6.4%

(n=13)

8%

(n=8)

16.4%

(n=27)

10.4%

(n=111)

Note: The gender of one producing group could not be identified and was not included in this analysis.

Gender differences across categories are depicted in Table 16. While males were the majority of

nominees in each category, females were most likely to be nominated for Best New Artist, followed by

Song of the Year. In the Record and Album of the Year categories, fewer than 10% of nominees were

women. For the first time in the seven years analyzed, a woman (Linda Perry) was nominated for

Producer of the Year.

Table 16

Grammy® Nominations by Gender and Category

Record of

the Year

Album of

the Year

Song of

the Year

Best New

Artist

Producer of

the Year

Total

Males

91.8%

(n=259)

93.4%

(n=520)

79.4%

(n=104)

58.9%

(n=33)

97.4%

(n=37)

89.6%

(n=953)

Females

8.2%

(n=23)

6.6%

(n=37)

20.6%

(n=27)

41.1%

(n=23)

2.6%

(n=1)

10.4%

(n=111)

Note: The gender of one producing group could not be identified and was not included in this analysis.

For female nominees, race/ethnicity was analyzed. Overall, 36.9% (n=41) of female nominees were

women of color. Differences in nominations for women of color by category are shown in Table 17. The

largest number of underrepresented females received nominations for Album of the Year, followed by

Record of the Year and Best New Artist—the latter category grew by 16.1 percentage points from last

year’s total.

Table 17

Female Grammy® Nominations by Underrepresented Status and Category

Record of

the Year

Album of

the Year

Song of

the Year

Best New

Artist

Producer of

the Year

Total

UR

34.8%

(n=8)

51.3%

(n=19)

18.5%

(n=5)

34.8%

(n=8)

100%

(n=1)

36.9%

(n=41)

Not UR

65.2%

(n=15)

48.7%

(n=18)

81.5%

(n=22)

65.2%

(n=15)

0

63.1%

(n=70)

The final analysis examines the frequency with which men and women were nominated. The list of overall

nominees was reduced to 608 individuals who were nominated for one or more Grammys in select

categories over the past seven years. Of these, 87.5% were male and 12.5% were female. This translates

to a ratio of 7 males to every 1 female.

For both men and women, the distribution of nominations was similar, save one category. Most

individuals received just one nomination between 2013 and 2019, though men were more likely to

receive five or more nominations than women were. For men, the range of nominations was 1 to 17 (Tom

Coyne) while for females it was 1 to 7 (Taylor Swift).

Table 18

Number of Grammy® Nominations by Gender

No. of Nominations

Males

Females

1

69.2% (n=368) 71.1% (n=54)

2

15.8% (n=84)

18.4% (n=14)

3

5.3% (n=28) 7.9% (n=6)

4

3.2% (n=17)

1.3% (n=1)

≥5

6.6% (n=35) 1.3% (n=1)

Total

532

76

Note: Columns total to 100%.

For women, we also examined nomination frequency by race/ethnicity. Of the 76 individual women,

61.8% (n=47) were white and 38.2% (n=29) were women of color. Again, there were no differences in the

frequency of nominations for white women and women of color. Most (72.4%=white vs. 70.2%=UR)

received only one nomination. Only two women over the last seven years have received more than three

nominations: Taylor Swift (7) and Beyoncé (4).

This section reveals that there is more progress to be made at the Grammys for women. Overall, 10% of

nominees in major categories over the last few years were female, with a slight improvement from 2018

to 2019. Notably, for the first time in the seven years we evaluated, a woman was nominated for

Producer of the Year. These promising changes reveal that the industry can take steps toward change, but

that progress must be accelerated.

Barriers Facing Female Songwriters & Producers in Music

Across seven years and 700 popular songs, 12.3% of songwriters and 2% of producers were female. These

figures beg the question: why? The purpose of this investigation was to understand the reasons for the

low numbers of women participating behind the scenes in the music industry. To that end, we conducted

a series of qualitative interviews to learn the impediments facing women in two positions: songwriting

and producing.

In the summer and fall of 2018, 75 interviews were conducted with female songwriters and producers.

10

Interviewees spanned genres and experience levels in music; 47% indicated they were songwriters, 9%

were producers, and 44% held both roles. The average age of participants was 33 (range=21-59). In terms

of racial/ethnic identification, 71% were white and 29% from an underrepresented racial/ethnic group.

Finally, 16% of participants worked outside the U.S.

Each participant was asked what barriers have you faced as a songwriter or producer in music? Responses

were spontaneous, with some receiving additional prompts. Answers were analyzed for similar themes

which pointed to the existence of a career impediment.

11

In their answer, individuals could indicate that

they had personally faced the barrier in question, could state that other women they knew faced the

barrier, or describe general situations they had heard about in the music industry. Each barrier is

described in this section alongside research that explains how it relates to career paths.

Figure 2

Barriers Facing Female Songwriters and Producers in Music

General Career Barriers

The first two spontaneous barriers indicated by participants were not gender-specific. More than one-

third (40%, n=30) of interviewees stated that they face difficulty navigating the industry, including

breaking into the business, making connections, and getting into different rooms. Given the complexities

of launching a creative career in a decentralized industry like the music business, this barrier is not

surprising.

A second impediment women stated was the financial instability associated with a music career.

Nineteen percent (n=14) of women described the lack of royalties available to songwriters and producers,

the changing nature of the industry due to streaming services, and the difficulties associated with

supporting oneself on the income generated from songwriting or producing. While financial uncertainties

associated with artistic careers are certainly difficult and noteworthy, they do not provide a full

explanation of why women work less than men. The problems associated with financial instability in

music can face both males and females, particularly as revenue models change.

43.0%

39.0%

36.0%

4.0%

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

Skills Discounted Stereotyped & Sexualized Male-Dominated Industry Work/Life Balance

Apart from these two categories, 11% (n=8) of interviewees stated that their age created a barrier. An

additional 11% (n=8) provided a series of other reasons why they faced impediments in music, which

were not related to their gender.

Women’s Skills and Abilities are Discounted

The first major barrier that faced female songwriters and producers was the consistent and persistent

dismissal of their work and contributions. A full 43% (n=32) of interviewees stated spontaneously that

two main issues confronted them as songwriters and producers. First, they were dismissed or not taken

seriously—their abilities, competence, and knowledge in the role of songwriter or producer were

doubted or were undercut by their colleagues. A second and related issue was that they had to prove

their competence to individuals who might work with them.

These two barriers—that women’s contributions are dismissed and that they must repeatedly prove

themselves to their male colleagues—create challenges in two ways. If women’s creative input is not

valued or doubted this could have an economic impact on the revenue they derive from their profession.

It also affects the experiences women have of bringing a creative product to fruition. When women must

prove their abilities to others before they are considered for employment or to ensure their contributions

are recognized, this might also impact their professional trajectory.

The dismissal of women’s contributions fits into a larger pattern of research on the perception of

women’s knowledge or ability by others. For example, evidence suggests that men and women use

gender as a reference when determining expertise.

12

Women may be perceived to hold less expertise or

competence than men, particularly in a stereotypically masculine domain.

13

The results of challenging

others in the workplace might also influence perceptions of women, who may even be punished for

violating gender norms.

14

When it comes to proving themselves, women may face a more difficult road than males, as they could

be subject to differing standards of competence or excellence.

15

In one study, researchers found that the

minimal competence standard for a female job applicant was lower than for a male.

16

However, the

female applicants faced higher standards than male applicants when the level of their ability was

considered. While women may be able to get their foot in the door, they may be plagued by the idea that

they are “good for a girl” rather than being seen as equally proficient at a task as their male colleagues.

At the crux of this barrier is the idea that men may resist women’s influence more than women resist

men’s influence. To more deeply probe this idea, we asked women a follow-up question about whether

their leadership or vision had been resisted by a colleague. 92% of women answered yes.

Women once again reported that they were ignored or discounted (43%, n=32) such that their

contributions were either not recognized or not taken seriously. Nearly one-third (29%, n=22) stated that

they were demeaned, or that others argued, embarrassed them or undermined their input. A further 19%

(n=14) said that women taking on leadership threatened men, while 16% (n=12) stated that stereotyping

about their gender was used to dismiss their work or their abilities. This could include individuals making

assumptions about women’s ability to lead or their technical proficiency.

While creative work may be shaped through the exchange of ideas and compromise between

collaborators, women’s experiences in music suggest this is not always the case. Instead, women

songwriters and producers work in environments and with individuals who dismiss their ideas, do not

acknowledge their abilities, and ignore their contributions. This sets up a system in which women must

continually prove their competence, talent, and skills to be considered and hired for work—particularly

when they are the only person of their gender in the room.

Sexualized & Stereotyped

The second impediment, reported by 39% (n=29) of participants in unprompted responses, was that

women’s careers are inextricably tied to expectations about their gender and sexual availability. Women

reported being sexualized (21% n=16), which included being the subject of innuendo, undesired

attention, propositioned, valued for their appearance, and even an awareness or fear of being personally

unsafe in work situations. One-quarter (25%) of interviewees (n=19) stated that gender stereotypes

guided others’ expectations about their behavior, treatment, or opportunities they were given. The

responses in this category illuminate that simply being a woman in music can serve as a barrier to career

success.

How do gender stereotypes influence career outcomes? According to one theorist, the stereotypes we

hold about gender can overlap or diverge from qualities associated with leadership.

17

In particular,

qualities associated with being female, such as being warm, supportive, or kind, are often not the traits

that describe successful leaders. In contrast, attributes that are typically viewed as masculine (e.g.,

ambitious, dominant, assertive) tend to align well with perceptions of leadership. There are at least two

potential consequences that emerge. One is that women may not be projected into leadership roles

because they are perceived to lack leadership qualities. The second is that women who hold leadership

positions may be punished if they behave in ways that are in line with more masculine leadership traits

and violate female gender roles. Women must walk a very fine line in order to both make career gains

and escape backlash.

In the music industry, this leadership paradox for women may be particularly difficult to negotiate when

the role of producer is considered. Across spontaneous interview responses, 12% (n=9) of participants

stated that the qualities associated with producing were associated with males—and that the job itself

was not viewed as something women could do. In other words, when individuals think producer, they

think male. This bias about who has the skills, background, or fits the cognitive profile of a producer

excludes women and may limit their career prospects. This finding aligns with a large body of global

research that suggests that when people “think manager, they think male.”

18

Stereotyping is not the only gender-based hurdle women face. The responses in this category also

indicated that women experience objectification by their colleagues and the wider industry.

19

According

to theorists, objectification occurs when an individual is viewed not as a whole person but instead as a

body and valued on the basis of how the body can be used or consumed. There are several consequences

of diminishing women to mere objects—both to the work context and to women themselves.

Research demonstrates that when women are objectified, they contribute less to groups and perform

less well on tasks, and that harassment can effect speech fluency.

20

Additionally, at least one study has

shown that focusing on a woman’s appearance (but not a man’s) can reduce perceptions of her warmth

and competence.

21

As noted earlier, perceptions related to both women’s fulfillment of gender roles

(e.g., warmth) or competence could lead to backlash or dismissal of her contributions.

When objectified (either by self or others), women’s state of “flow,” a focused state of working, can be

interrupted.

22

One example of this occurs when women must negotiate the objectifying gaze or potential

advances of a male colleague while simultaneously trying to accomplish creative work. Objectification

also has potential consequences for women’s psychological health. The internalization of objectification,

a process called self-objectification, affects some women situationally and others habitually. Self-

objectification can lead to other adverse mental health outcomes, such as body shame.

23

Apart from spontaneous answers that pointed to sexualization and stereotyping, interviewees also

answered a question that specifically asked whether any aspect of the environment of the recording

studio had ever made them feel uncomfortable or uneasy. More than three-quarters (83%) of

participants said that they or other women experienced discomfort in the studio, with 68% specifying that

they themselves had felt this way. Further comments on the question were coded into categories that

represent the reasons participants felt uneasy in the studio.

More than one-third of interviewees (39%, n=24) stated that they had been objectified, hit on, or

experienced sexual innuendo while working. Women recounted experiences in which their safety was a

concern, from attending sessions in remote studios or someone’s home, late at night or with strangers. A

second category of responses (25%, n=19) pointed to being the lone female or one of few women in

environments populated by males. The third source of discomfort (28%, n=21) was having their

contributions, knowledge, or expertise dismissed or even facing hostile language from others. Fourth,

20% (n=15) of interviewees noted that drugs, alcohol, and sexualized women were part of studio culture,

and that being surrounded by intoxication fostered nervousness. Finally, 11% (n=8) of respondents

provided other reasons for their uneasiness, such has feeling under pressure to create a good song,

particularly while others were watching.

The recording studio and the music industry more broadly are sites where women feel that their

appearance and gender mark them for unwanted attention. Additionally, gender stereotypes thwart

women’s ability to participate across the music business in all roles. It is clear that women in music face a

work environment in which their gender makes them primarily valuable for one thing—and it is not their

talent.

Male-Dominated Industry

The third major barrier stated in their initial response by 36% of participants (n=27) occurred as the result

of being a statistical minority in the music business. A full 29.3% (n=22) of interviewees in this category

stated that the music industry was male-dominated or functioned as the proverbial ‘boy’s club.’ This

category also included responses (12%, n=9) who stated that there were few females in songwriting and

production, including few female role models, and the handful of responses (4%, n=3) indicating that

women were competitive with each other.

That music is predominantly created by males—particularly popular music—can be objectively verified,

and has been by reports such as this one. Yet, it is more than the numerical disparity between men and

women that creates a barrier for female songwriters and producers. Being outnumbered by men can

affect women in multiple ways.

The experience of being alone in a group is what researchers have termed solo status.

24

The negative

effects of solo status for women may include decreased task performance and among some, changing

response style to less detailed language.

25

If women are, as we note above, already at risk for being

dismissed or discounted then this may be amplified when they are the only woman in the workgroup.

A second risk to women which is borne out by the spontaneous and prompted answers above, is either

real or threatened forms of gender-based or sexual harassment. Research has shown that these

behaviors are more likely to occur when women have greater contact with males in the workplace.

26

Additionally, sexual or gender-based harassment may be more likely to occur to women who embody

more masculine traits—or who work in more male-dominated environments.

27

To further understand women’s solo status or isolation, we explored quantitative data. After removing

duplicate songs from the sample outlined earlier, we examined 633 popular songs from 2012 to 2018.

Across these songs, 56.9% did not feature even one female writer. When women are present, they are

often alone—31.6% of songs had just one female writer involved. A mere 11.5% of songs had 2 or more

female writers credited. At most, a song had 6 female writers involved. In contrast, up to 16 men were

involved with a song. Only 3 songs in the sample, or less than 1% of 633 songs, did not feature a male

songwriter. Males are also solo contributors to just 9.6% of songs. Thus while women are excluded or

alone on 88.5% of the most popular songs over the last 7 years, men face solo status or erasure on only

10% of these tracks.

Beyond often working alone, a secondary barrier related to working in a male-dominated industry cited

by participants was the lack of role models in songwriting and producing. Women stated that there were

not robust examples of women doing these jobs or shown in other aspects of the music industry such as

playing instruments or working as engineers. However, not all role models are created equal. Research in

computer science reveals that for young women, stereotypical role models of either gender are likely to

repel interest and perceived success in the field. The same is true of environments; when young women

encounter environmental cues that are evocative of computer stereotypes, they are less likely to pursue

the major.

This evidence suggests that expanding women’s interest in music production and songwriting entails

more than ensuing that role models exist. It is imperative that role models do not evoke negative

stereotypes that may decrease interest.

28

At least one other investigation examined how women’s career

aspirations can be influenced by experiencing stereotype threat, or the fear of confirming a negative

stereotype about their gender.

29

In this context, women who were skilled mathematically opted for fields

that were more in line with stereotypically feminine occupations, such as journalism, communication, or

writing instead of technical fields such as engineering or accounting.

One way stereotyping may be communicated is through the pervasive sexualization of women in music.

As noted earlier, women face a climate of objectification in the recording studio. Song lyrics themselves—

especially those with male artists—include references to women’ bodies or sexual activities,

30

making not

only the workplace but the work product a source of objectification. An awareness of these stereotypes

may decrease the likelihood that women will want to pursue a career in the field.

Work and Life Balance

The difficulty of balancing both professional and personal demands was also explored. Few participants

overall (4%, n=3) spontaneously mentioned that work and life balance created a career impediment. We

further probed this topic with a focused question: “To what extent is balancing work and family life an

issue in your career?” This revealed that 70.7% (n=53) of participants personally find this challenging and

an additional 13.3% (n=10) indicated while it might not be a problem for them, other women across the

business might see this as a barrier.

Over half (54.7%, n=41) of participants indicated that their relationships suffered as a result of the

demands of work. These relationships included ties to romantic partners, family members, or friendships.

Interviewees stated that they did not have the time to invest or nurture these bonds, that working in

music put pressure on relationships, or that they chose not to foster these connections. In line with this

category, 25.3% (n=19) of participants indicated that they prioritized their career over relationships or

other aspects of their lives.

A few other issues emerged that created challenges or illuminated how participants strive to create

balance. Roughly ten percent (10.7%, n=8) of participants said that they faced mental or physical health

issues due to the demands of the field. Gender roles and industry biases that make balancing professional

and personal demands a greater burden for women to bear were commented on by 20% (n=15) of

participants. Eight percent said that their family life impacted their career and/or they felt guilt about

their choices. Seven respondents (9.3%) indicated that they put off having children in order to focus on

their careers. Finally, 25.3% (n=19) of those interviewed indicated they did not have children at present.

The challenge of balancing demanding careers with personal relationships and family life is not unique to

music. It has emerged in studies related to females behind the camera in film,

31

and having children or

caring for older relatives affects women to a larger extent than men, even interfering with work

responsibilities.

32

Despite this reality, the need to balance personal and professional concerns may

restrict the opportunities women are able to take, but is not sufficient to explain the low percentages of

women in the field overall.

Women of Color Face Unique Impediments

While few of the individuals (3%, n=2) interviewed stated that being from an underrepresented

racial/ethnic group created an impediment to their careers, a follow up question yielded more

information. More than 80% (82.3%, n=14) of the women from underrepresented racial/ethnic

backgrounds prompted on the topic (n=17 of 21) indicated either directly or indirectly that their

race/ethnicity created a barrier to their work in music.

These women reported that they were not considered (58.8%, n=10) for certain projects when their

identity was clear before they met someone, that they were rejected for certain opportunities, or not

taken seriously, and that they were not seen as marketable. Additionally, 29.4% (n=5) said they were

stereotyped in terms of the genre in which they could work. Similarly, 29.4% (n=5) said they did not

receive support in the form of acceptance, praise, or that they were only respected within their in-group.

Finally 29.4% (n=5) stated that they were hired based on their token status or that they were the only

person of color in the room.

Research supports the idea that women of color face greater hurdles than their white female

counterparts across industries. Studies show that women from underrepresented racial/ethnic

backgrounds are disadvantaged for promotions, may experience a larger wage gap, and feel that they lack

access to mentorship, informal relationships with co-workers, role models, and assignments that bring

visibility.

33

In other facets of entertainment, women of color are far less likely that their white female

colleagues to work as film or TV directors, film producers, executives, in notable below-the-line positions,

and as film critics.

34

In a previous study on barriers facing underrepresented film directors, women of

color indicated that the influence of both their gender and race limited their career opportunities.

35

As

noted above, only 4 women of color worked as producers across 400 songs from 2012 to 2018—

providing further evidence that in music women of color confront obstacles that their white female peers

do not.

Additional Barriers

In addition to what is described above, a small percentage of women described additional barriers that

they faced. Each will be described briefly.

Nine percent (n=7) of women stated that there were internal barriers that created difficulties for them in

their work in the music industry. This included lacking confidence, knowledge, or perceiving that their

own abilities were limited. While women may legitimately feel that they need to enhance their skills,

knowledge or abilities in their chosen field, other factors may be at work. Research suggests that

individuals may self-stereotype, particularly if their gender identity is more salient.

36

After working in a

business rife with gender stereotypes, women may be more likely to view themselves as their industry

sees them.

Eleven percent (n=8) of participants indicated that the music industry was more difficult for women

generally, without offering additional information on how or why that might be the case. Finally, 4% (n=3)

of participants stated that to find success they pursued work on their own terms. By choosing to operate

outside of closed networks, they were able to create opportunities.

The results of the qualitative analysis provide an explanation for the lack of women in music. Through

women’s own words and experiences, it is clear that the way they are viewed and treated in the industry

prevents more women from exploring careers in music. What follows are closing thoughts on the data

presented here and solutions to remedy the ongoing exclusion of women in songwriting and producing.

Conclusion

The purpose of this study was twofold. First, we updated our initial study on the prevalence of women

and people of color working as artists, songwriters and producers in popular music. The results revealed

that little has changed in the last year. Second, we explored the reasons why so few women work as

songwriters and producers in the industry. Through interviews with 75 individuals employed in this

capacity, the experiences of women in music illuminated the impediments women face.