Hastings Communications and Entertainment Law Journal

.+3,$

8

3,!$0 02("+$

Newton v. Diamond: Measuring the Legitimacy of

Unauthorized Compositional Sampling— A Clue

Illuminated and Obscured

Susan J. Latham

.++.52'(1 -# ##(2(.- +5.0*1 2 ':/10$/.1(2.063"' 12(-&1$#3

' 12(-&1".,,$-2+ 5).30- +

02.%2'$ .,,3-(" 2(.-1 5.,,.-1 -2$02 (-,$-2021 -#/.021 5.,,.-1

-#2'$ -2$++$"23 +0./$026 5.,,.-1

9(102("+$(1!0.3&'22.6.3%.0%0$$ -#./$- ""$11!62'$ 5.30- +1 2 12(-&1"'.+ 01'(/$/.1(2.062' 1!$$- ""$/2$#%.0(-"+31(.-(-

12(-&1.,,3-(" 2(.-1 -#-2$02 (-,$-2 5.30- +!6 - 32'.0(7$#$#(2.0.% 12(-&1"'.+ 01'(/$/.1(2.06.0,.0$(-%.0, 2(.-

/+$ 1$".-2 "2 5 -& -&$+ 3"' 12(-&1$#3

$".,,$-#$#(2 2(.-

31 - 2' , Newton v. Diamond: Measuring the Legitimacy of Unauthorized Compositional Sampling— A Clue Illuminated and

Obscured;AB=?<A @>> ?B

4 (+ !+$ 2':/10$/.1(2.063"' 12(-&1$#3' 12(-&1".,,$-2+ 5).30- +4.+(11

119

Newton v. Diamond: Measuring the

Legitimacy of Unauthorized

Compositional Sampling—

A Clue Illuminated and Obscured

by

S

USAN

J. L

ATHAM

*

I. Introduction .......................................................................................121

II. A Brief History .................................................................................122

A. What is Digital Sampling, How Did it Start, and Why is it

Done? ............................................................................................122

B.

Grand Upright Music Ltd. v. Warner Bros. Records, Inc.

:

An

End to the Feast ...........................................................................123

III. Statutory Framework: Two Separate Copyrighted Works.........124

IV.

Newton v. Diamond

: The District Court Illuminates a Clue......127

A. The Facts and Claims....................................................................127

B. The Judgment and Analyses ........................................................128

1. Protectability of the Portion Sampled......................................128

2. Doctrine of De Minimis Use .....................................................132

3. Int

ernational Copyright Infringement and Limitation of

Damages ..........................................................................................134

V.

Newton v. Diamond

: The Court of Appeals Obscures a Clue.....134

A. The Judgment................................................................................134

B. Analysis of the Court

⎯

The Doctrine of

De Minimis

Use .......135

VI. Reality Check ..................................................................................137

A. Which is the Path to Reasonable Determination?....................137

B. The Conundrum of

De Minimis

Use Analysis...........................139

VII. Conclusion ......................................................................................146

*

LL.M. in Intellectual Property, Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law, expected June

2004; J.D., Florida State University College of Law, May 2003. The author expresses her

gratitude to Prof. Justin Hughes of the Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law, Prof.

Frederick Abbott of Florida State University College of Law, Mr. Alvin Deutsch, Esq. of

McLaughlin & Stern, LLP, and Mr. Robert McNeely, Esq. for the knowledge, guidance,

and insight each generously shared through their teaching and consultations.

120 H

ASTINGS

C

OMM

/E

NT

L.J. [26: 119

Appendix.................................................................................................148

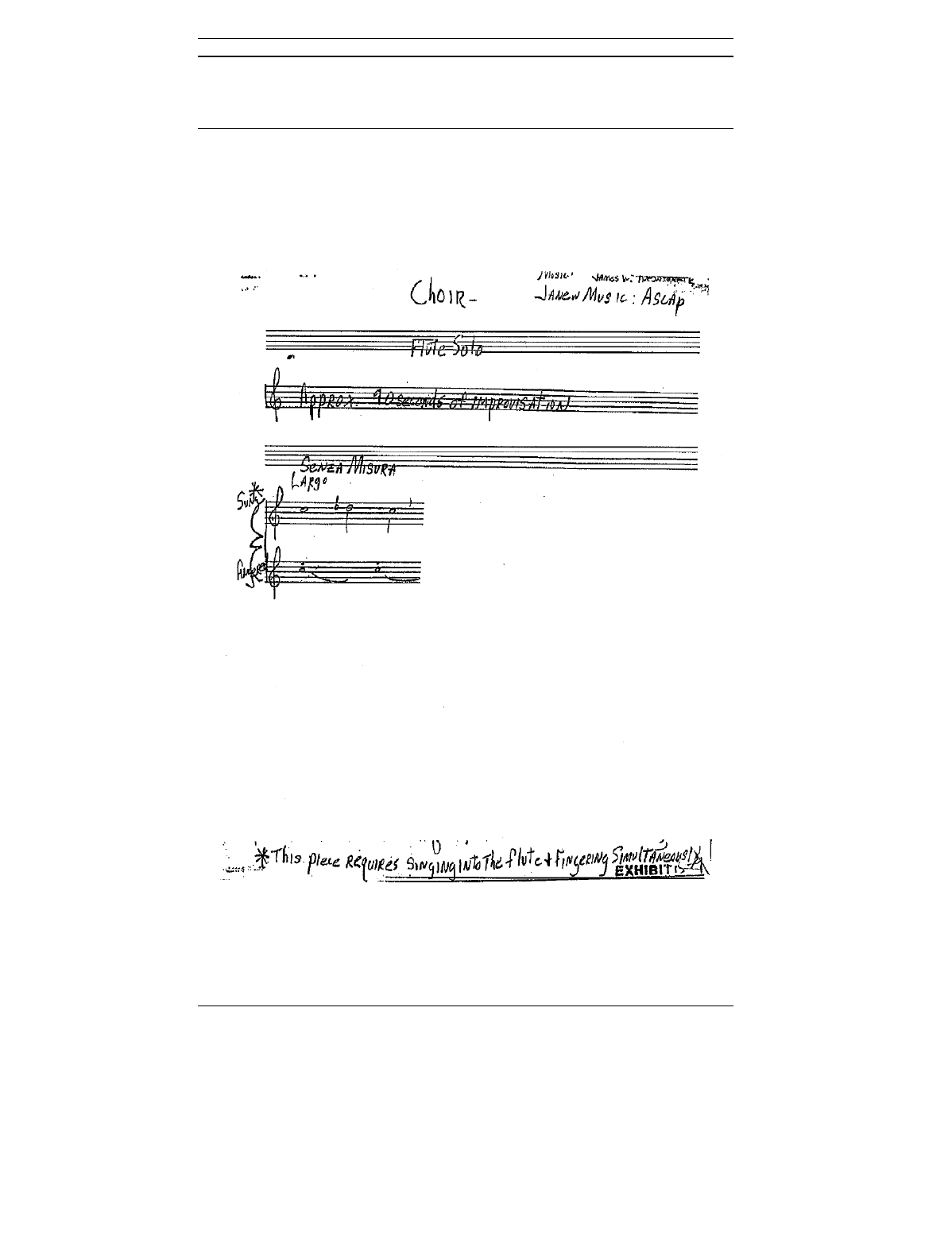

Figure 1:

Choir

: The Musical Score for the Sampled Sequence....148

Diagram #1:

Newton v. Diamond’s

Two Separate Copyrighted

Works.............................................................................................149

Diagram #2:

Newton I

on Analytic Dissection of the Musical

Composition vs. Sound Recording.............................................150

Diagram #3:

Newton I

on the Protectability of a Particular

Segment of a Copyrighted Musical Composition.....................151

Diagram #4:

Newton I’s

De Minimis

Use Analysis ........................153

2003]

N

EWTON V

. D

IAMOND

121

I. Introduction

It seems to be a widely accepted truism that the wealth of

creative works amassed throughout our cultural history serves as a

foundation for each generation of new works.

1

For most of our

copyright history, and despite the occasional overreaching by some

authors of new works, this truism was fairly palatable to most because

it expressed the norms of subtle inspiration and creative

transformation rather than wholesale lifting of original creative

expression. However, with the emergence of the musical genre called

“hip-hop,” a new generation of authors elevated this foundational

concept from a subtle truism to a conspicuous mantra through the

practice of unlicensed digital sampling.

2

And suddenly, many within

the music industry and judicial branch found this modern incarnation

of a previously palatable truism hard to swallow.

3

This article will discuss the ramifications of that sudden distaste

and the current outlook for the future of digital sampling. Part Two

will begin the discussion with a brief history of digital sampling and its

initial legal challenge. Part Three will lay out the statutory framework

underlying musical works as a necessary precursor to an

understanding of the rights involved. Part Four will then delve into a

thorough examination of the district court opinion in

Newton v.

Diamond

4

(

Newton I

), which had the potential to cleanse palates and

help delineate where the buffet line for unlicensed samples may

begin. Thereafter, part Five will review the subsequent Ninth Circuit

opinion in

Newton v. Diamond

5

(

Newton II

). Part Six will compare

the

Newton I

and

II

decisions and evaluate the current state of

de

minimis

use analysis. Finally, part Seven will conclude this article with

a discussion of the implications the

Newton v. Diamond

decisions

have for the future practice of digital sampling.

1

.See

Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music, Inc., 510 U.S. 569, 575-576 (1994); Emerson v.

Davies, 8 F.Cas. 615, 619 (No. 4,436) (CCD Mass. 1845); Carey v. Kearsley, 4 Esp. 168,

170, 170 Eng.Rep. 679, 681 (K.B. 1803).

2

.See

generally

D

ONALD

S. P

ASSMAN

, A

LL

Y

OU

N

EED TO

K

NOW

A

BOUT THE

M

USIC

B

USINESS

(4th ed., Simon & Schuster 2000) (1991); Brett I. Kaplicer, Note,

Rap

Music and De minimis Copying: Applying the Ringgold and Sandoval Approach to Digital

Samples

, 18 C

ARDOZO

A

RTS

& E

NT

. L.J. 227 (2000); Henry Self,

Digital Sampling: A

Cultural Perspective

, 9 UCLA E

NT

. L. R

EV

. 347 (2002).

3

.E.g

., Grand Upright Music Ltd. v. Warner Bros. Records, Inc., 780 F. Supp. 182

(S.D.N.Y. 1991).

4. Newton v. Diamond, 204 F. Supp.2d 1244 (C.D.Cal. 2002).

5. Newton v. Diamond, 349 F.3d 591 (9th Cir. 2003).

122 H

ASTINGS

C

OMM

/E

NT

L.J. [26: 119

II. A Brief History

A. What is Digital Sampling, How Did it Start, and Why is it Done?

Digital sampling is the electronic extraction of a portion of an

existing musical work and its subsequent insertion into a new sound

recording,

6

while its corollary, looping, is the repetitive re-playing of

the sample within the new work.

7

The roots of hip-hop music and the

practice of digital sampling have been attributed to the innovation

occurring among disc jockeys (D.J.s) or “selectors” on the island of

Jamaica between the late 1950s and 1960s.

8

The innovation began as

a bold change from simply announcing selections in between the

music to “talking-over” the records as they played in a chant-like

manner that blended Black American slang with the distinctive West

Indian dialect of Patois.

9

As the practice became popular with live

audiences, D.J.s competed for the respect of fledgling fan bases and

many began commissioning Jamaican-styled instrumentals that

mimicked American “soul” hits.

10

The D.J.s were no longer

inconspicuously serving up music from the background; they had

become part of a blended musical performance and their “talk-overs”

were just as great of a draw as the music itself.

11

In 1974, a transplanted Jamaican D.J. named Clive Campbell,

a.k.a. “Kool Herc,” introduced the “talk-over” technique in New

York and adapted it to the “break dancing” movement rising from

the clubs of the South Bronx.

12

As dancers displayed their dexterity

and flexibility on the dance floor, “Kool Herc” exhibited his dexterity

and flexibility on the turntable by isolating and manipulating the

crucial instrumental breakdowns of various funk records.

13

And, just

6. Oren J. Warshavsky & Jay L. Berger,

Will Case Change Law on Sampling?:

District Court Found That Three-Note Sample Did Not Infringe the Copyright in a

Composition

, N

AT

’

L

L.J., Oct. 14, 2002, at C1.

7. A. Dean Johnson,

Music Copyrights: The Need for an Appropriate Fair Use

Analysis in Digital Sampling Infringement Suits

, 21 F

LA

. St. U. L. R

EV

. 135, 161 n. 174

(1993).

8

.See

Self,

supra

note 2; B

ILL

B

REWSTER

& F

RANK

B

ROUGHTON

, L

AST

N

IGHT A

DJ S

AVED

M

Y

L

IFE

: T

HE

H

ISTORY OF THE

D

ISC

J

OCKEY

(1999); D

AVID

T

OOP

, R

AP

A

TTACK

: A

FRICAN

R

AP TO

G

LOBAL

H

IP

H

OP

(3d ed. 2000); Robert M. Szymanski,

Audio Pastiche: Digital Sampling, Intermediate Copying, Fair Use

, 3 UCLA E

NT

. L. R

EV

.

271, 277 (1996).

9. Self,

supra

note 2, at 348.

10.

Id

.

11.

Id

. at 349.

12.

Id

. at 349-50.

13.

Id

.

2003]

N

EWTON V

. D

IAMOND

123

as had occurred in Jamaica, imitation and innovation among D.J.s

catapulted the genre to widespread popularity.

14

Sampling became digital and ubiquitous in the mid-1980s with

the commercial availability of the musical instrumental digital

interface (MIDI) device.

15

This electronic device allowed hip-hop

producers to easily recreate in the studio what the D.J.s had been

doing by extreme manual dexterity in the clubs.

16

Consequently, the

hip-hop artist was able to gain the use of a distinctive sound with little

expenditure of physical or financial capital and take advantage of any

public appeal the sampled sound had already garnered.

17

B. Grand Upright Music Ltd. v. Warner Bros. Records, Inc.:

18

An End to

the Feast

In the nascent stages of sampling, as artists were feeding off

samples of the distinctive sounds of prior works, the prevalent

attitude was “catch me if you can” and many hip-hop recordings were

being released without any attempt to license either the sound

recording or the musical composition from which the sample was

derived.

19

However, in the same district where the practice began, the

digital gluttony transpiring in hip-hop was brought to an end in 1991

via the terse opinion by District Judge Kevin Thomas Duffy in

Grand

Upright Music Ltd. v. Warner Bros. Records, Inc

.,

20

the first case to

confront unlicensed digital sampling.

In

Grand Upright Music

, the rap artist Biz Markie sampled three

words and a short keyboard riff from the Gilbert O’Sullivan

composition and recording of “Alone Again (Naturally).” However,

the opinion neither addressed the protectability of these elements nor

the substantial similarity of defendant’s use of them.

21

Instead, the

court began and ended its analysis with the first prong of an

infringement claim: ownership of the copyrighted work.

22

Further, by

opening its opinion with the biblical admonishment “thou shalt not

14

. See id.

15. Warshavsky & Berger,

supra

note 6; Kaplicer,

supra

note 2, at 228.

16

.See

Self,

supra

note 2, at 350.

17. Kaplicer,

supra

note 2, at 228.

18. 780 F. Supp. 182 (S.D.N.Y. 1991).

19. P

ASSMAN

,

supra

note 2, at 306-307;

see

Warshavsky & Berger,

supra

note 6.

20. 780 F. Supp. 182 (S.D.N.Y. 1991).

21. Stan Soocher,

Judicial Guidelines Mature for Sampling Copyright Issues

,

in

E

NTERTAINMENT AND

S

PORTS

L

AW IN THE

N

EW

E

CONOMY

(ABA Forum on the

Entertainment and Sports Industries CD-ROM, 2003 Annual Meeting October 10-11,

2003).

22.

Grand Upright Music Ltd.,

780 F. Supp. at 183.

124 H

ASTINGS

C

OMM

/E

NT

L.J. [26: 119

steal”

23

and closing it with a referral of the matter to the U.S.

Attorney for consideration of criminal charges (noting the

defendants’ “callous disregard for the law”),

24

the court struck fear

into the music industry and left behind the impression of a per se bar

to unlicensed digital sampling.

25

Consequently, the pendulum swung

in the direction of extreme caution, or paranoia, and the licensing of

digital samples skyrocketed.

26

Since

Grand Upright Music

, two phenomena have coalesced to

keep the pendulum stuck on the side of extreme caution. First, most

sampling cases continue to be disposed of via settlements between the

parties.

27

Second, despite an evolution of the legal reasoning

employed in digital sampling cases to include the more sophisticated

analyses common among other subjects of civil copyright

infringement actions, the courts have not elucidated guideposts for

lawful digital sampling.

28

Consequently, digital sampling has been

trapped in a discordant culture of social popularity and legal

uncertainty from which artists and record companies have had only

two unsatisfactory means of egress: one, the path of improvidence—

doling out steady streams of preventative payments; the other, the

path of imprudence—daring the copyright holders of sampled works

to “catch me if you can.” What has been missing and sorely needed is

a third path, a path of reasonable determination—via which the risk

of infringement may be reasonably estimated and prudent (rather

than paranoid or careless) decisions regarding the need for a sample

license may be made. In 2002, District Judge Nora M. Manella of the

Central District of California may have finally blazed that trail in

Newton v. Diamond (Newton I)

.

III. Statutory Framework: Two Separate Copyrighted Works

Before delving into

Newton I

, it is important to understand the

statutory framework underlying musical works. For every

embodiment of a musical work in a phonorecord since February 15,

1972, there are two copyrights involved: one protecting the

23

.Id

.

24

.Id

. at 185.

25

.See

Warshavsky,

supra

note 6; P

ASSMAN

,

supra

note 2, at 307.

26

.See

Warshavsky,

supra

note 6; P

ASSMAN

,

supra

note 2, at 307.

27. Soocher,

supra

note 21, at 18.

28.

Id

. at 18-19. The judicial tools employed by courts in the analysis of digital

sampling cases may have matured. However, a premise of this article is that despite the

use of these tools of legal reasoning, the courts have not yet applied those tools in a

manner that clearly delineates boundaries for lawful digital sampling.

2003]

N

EWTON V

. D

IAMOND

125

composition, and the other protecting the sound recording.

29

Notably,

it is generally accepted that nothing in the law requires the copyright

owner of either to allow others to use a digital sample of his or her

work.

30

Section 114(b) of the Copyright Act precludes such a

requirement for sound recordings and Section 115(a)(2) excludes it

from the requirement for musical compositions.

31

First, by clarifying the rights of a sound recording copyright

owner in regard to derivative works, Section 114(b) makes it clear

that the digital sampling of a copyrighted sound recording must

typically be licensed to avoid an infringement. Section 114(b) states

that:

The exclusive right of the owner of copyright in a sound recording

under [the Section 106 right to prepare derivative works] is limited

to the right to prepare a derivative work in which the

actual sounds

fixed in the sound recording

are rearranged, remixed, or otherwise

altered

in sequence or quality.

32

The import of this language is that it does not matter how much a

digital sampler alters the actual sounds or whether the ordinary lay

observer can or cannot recognize the song or the artist’s performance

of it.

33

Since the exclusive right encompasses rearranging, remixing,

or otherwise altering the actual sounds, the statute by its own terms

precludes the use of a substantial similarity test.

34

Thus, the defenses

available to a defendant are significantly limited.

35

Second, the compulsory mechanical license provisions of Section

115 do not provide for the compulsory licensing of digital samples.

Specifically, Section 115(a)(2) states that:

A compulsory license includes the privilege of making a musical

arrangement

of the work

to the extent necessary to conform it to

the style or manner of interpretation of the performance involved,

but

the arrangement

shall not change

the basic melody or

fundamental character of the work

,

and

shall not be subject to

29. 17 U.S.C. § 102(2), (7) (1996).

30

.See

P

ASSMAN

,

supra

note 2, at 307.

31

.

17 U.S.C. §§ 114(b), 115(a)(2) (2003).

32.

Id

. at § 114(b) (emphasis added).

33. Justin Hughes, Copyright Lecture Notes (October 16, 2003) (on file with the

author).

34. Forensic proof will likely be adequate for “unrecognizable” uses.

See

id.

35. There may be the possibility of a

de minimis

use defense, depending on how

strictly the court interprets the “actual sounds” language in the statute. However, a fair

use defense also seems to be limited by § 114(b) to use within noncommercially distributed

educational television and radio programming.

See id.

126 H

ASTINGS

C

OMM

/E

NT

L.J. [26: 119

protection as a derivative work

under this title, except with the

express consent of the copyright owner.

36

This language dictates that those seeking to benefit from the

compulsory licensing of a copyrighted composition for the

manufacture and distribution of phonorecords must abide by three

parameters. They must: (1) use the entire work; (2) not alter the

basic melody or fundamental character of the work in the new

performance;

37

and (3) not seek copyright protection for the

derivative work without the express permission of the composition’s

copyright owner. By nature, however, digital sampling will generally

run afoul of all three parameters by: (a) extracting only select

elements of work rather than using the work as a whole; (b) altering

the fundamental character of the work by rearranging and looping

those select elements (often combining them with still more samples

from other works) into an entirely new work possessing an entirely

different meaning or significance; and finally, (c) making derivative

use of the extracted elements within a new composition and sound

recording for which copyright protection is sought without express

permission from the copyright holder.

Notably, in contrast to the sound recording copyright owner’s

right to prepare derivative works, there has been no tailoring of the

derivative works right available to the copyright owner of a musical

composition to expressly preclude second-comers from rearranging,

remixing, or otherwise altering the composition. Sound recordings are

different animals. While their copyright owners generally have fewer

exclusive rights than copyright owners of other subject matter—such

as musical compositions—when it comes to digital sampling, the

sound recording copyright operates more resolutely. Consequently,

this distinction between sound recordings and musical compositions

places the centrifugal force of the legal uncertainty surrounding

digital sampling squarely within the copyright in the musical

composition.

36. 17 U.S.C. § 115(a)(2) (2003) (emphasis added).

37. For example, the composer of a religious spiritual may argue that recording a

techno dance version of his or her song violates Section 115(a)(2) by altering the song’s

fundamental character. Justin Hughes, Copyright Lecture Notes (Oct. 15, 2003).

2003]

N

EWTON V

. D

IAMOND

127

IV. Newton v. Diamond: The District Court Illuminates a Clue

A. The Facts and Claims

The copyrighted work at the center of the

Newton v. Diamond

digital sampling controversy is a composition for flute and voice

entitled “Choir.” The work was composed and registered with the

United States Copyright Office in 1978 by James W. Newton, a

composer and accomplished flutist. However, in 1981, Mr. Newton

recorded his performance of “Choir” and licensed all his rights in the

sound recording to ECM Records for the sum of $5,000. Thus, ECM

Records became the copyright owner of the sound recording of

“Choir.”

In February of 1992, while preparing their album “Check Your

Head,” a hip-hop group called the Beastie Boys paid ECM Records a

flat, one-time fee of $1,000 in exchange for an irrevocable sample

license. The license granted the Beastie Boys the nonexclusive right

to use portions of the “Choir” sound recording in all versions of their

song “Pass the Mic.” Thus, pursuant to this license, the Beastie Boys

digitally sampled and looped the opening six seconds of the “Choir”

sound recording, so that it actually appears over forty times

throughout various renditions of “Pass the Mic.” The Beastie Boys,

however, did not obtain a license from Mr. Newton.

The sampled six-seconds of the approximately four-and-a-half-

minute “Choir” sound recording consists of a three-note sequence

whereby Mr. Newton fingers a C-note while simultaneously singing

into the flute a C, vocally ascending to a D-flat, then descending back

to a C. This particular sequence appears only once in the musical

composition. Notably, the only elaboration of the musical score for

this sequence are the notations “

senza misura

” (without measure)

and “

largo

” (slowly), along with the footnote: “This piece requires

singing into the flute [and] fingering simultaneously.”

38

Mr. Newton alleged that the Beastie Boys were legally obligated

to obtain a separate license from him for their derivative use of his

musical composition. Thus, because of their failure to do so, Mr.

Newton asserted four separate claims against the Beastie Boys: (1)

copyright infringement; (2) international copyright infringement; (3)

reverse passing off; and (4) misappropriation of identity. Although

the third and fourth claims were dismissed, the claims for copyright

38. A copy of the musical score for the sampled sequence has been included in the

Appendix,

infra

.

128 H

ASTINGS

C

OMM

/E

NT

L.J. [26: 119

infringement survived and became the focus of this opinion on the

parties’ cross-motions for summary judgment.

In defense of the action, the Beastie Boys argued that the sample

was not protectable as a matter of law and that, even if it was

protectable, their use of it was merely

de minimis

and, thus, not

actionable. Further, they argued that since the domestic copyright

infringement claim could not be proved, the international claim must

also fail. Finally, they asserted that since there is a three-year statute

of limitations per 17 U.S.C. § 507(b), any damages would be limited

to only those accruing after April 9, 1998—the date three years prior

to the filing of Mr. Newton’s claim.

B. The Judgment and Analyses

So, were the Beastie Boys obligated to obtain a separate sample

license from the copyright owner of the musical composition

“Choir”? The court did not believe so and granted the Beastie Boys’

motion for summary judgment while denying Mr. Newton’s.

39

Since Mr. Newton was not the owner of the sound recording and

the Beastie Boys had properly licensed the sound recording, the

court’s decision depended upon the resolution of two key issues

underlying Mr. Newton’s general allegation. First, whether the three-

note sequence as embodied in the musical composition, absent the

distinctive sound elements created by Mr. Newton’s performance

techniques, is protectable under copyright law.

40

Second, if the

composed sequence is protectable by copyright, whether the Beastie

Boys’ unauthorized use of it infringed Mr. Newton’s exclusive rights

in the composition.

41

1. Protectability of the Portion Sampled

42

a. Analytic Dissection

As a fundamental matter, the district court held that the portion

of the musical composition sampled by the Beastie Boys is not

protectable as a matter of law.

43

To arrive at this finding, the court

began with an analytic dissection of “Choir” to filter out the elements

39. Newton v. Diamond, 204 F. Supp. 2d 1244, 1245, 1260 (C.D.Cal. 2002).

40

.Id

. at 1249.

41

.Id

. at 1256.

42. To aid the reader in more clearly following the district court’s analysis of the

sample’s eligibility for protection, a flow chart of the court’s analysis is presented in

Diagrams #2 and #3 in the Appendix,

infra

.

43.

Newton

, 204 F. Supp. 2d at 1253, 1256.

2003]

N

EWTON V

. D

IAMOND

129

that are unique to the sound recording and determine the scope of

protection available to the musical composition.

44

The court noted

that a musical composition consists of rhythm, harmony, and melody

expressed in written form.

45

Thus, to the extent those compositional

elements are elaborated within the score, the sounds that would

necessarily result from anyone’s performance of them are protected.

46

In other words, the generic performance of the written composition is

protected. However, to the extent a performer further elaborates

upon the musical composition during his recorded performance, those

unique elements of the sound recording are beyond the scope of

protection for the composition and must be filtered out of the court’s

analysis.

47

Here, the sampled sequence consists of a musical technique

called “vocalization.”

48

However, unfortunately for Mr. Newton, his

experts focused so intently upon convincing the court of the

uniqueness of Mr. Newton’s mastery of this technique that they failed

to appreciate the distinction between the composition and the sound

recording.

49

The plaintiff’s experts testified that Mr. Newton’s unique

approach to vocalization—dubbed the “Newton Technique”—uses a

combination of refined breath control and overblowing to produce

multiple pitches or “multiphonics.” However, none of the

characteristics that the plaintiff’s experts explained as comprising the

Newton Technique were written into the musical score.

Consequently, those specific techniques, unique as they may be, are

protected only by the copyright in the sound recording—not the

copyright in the musical composition.

50

b. Originality

Despite the plaintiff’s argument to the contrary, the court

affirmed that the presumption that attaches to a work upon federal

registration is one of validity of the copyright, not of the originality of

all its individual elements.

51

Instead, the originality of a work’s

individual elements is a matter of law to be decided by the judge.

52

In

44

.Id

. at 1249-52.

45

.Id

. at 1249.

46

.Id

.

47

. See id

. at 1251.

48

.Newton

, 204 F. Supp. 2d at 1250.

49

.Id

. at 1250-52.

50

.Id

. at 1251.

51

.Id

. at 1252.

52

.Id

. at 1253.

130 H

ASTINGS

C

OMM

/E

NT

L.J. [26: 119

making that determination, the court stated it must be cognizant of

the limited amount of raw material (notes and chords) available to

composers and the consequent recurrence of common themes among

various compositions, especially in popular music.

53

Keeping this in

mind, the district court’s analysis explained the divide between

common and original compositional elements.

The court revealed two basic routes to a finding of commonality,

or an absence of non-trivial creative contribution. First, the court

highlighted a line of cases in which the copied portion of the

composition consisted of three notes or less.

54

Along this route, the

court found the facts of

Jean v. Bug Music, Inc

.

55

“strikingly similar.”

56

There, the court held that a three-note sequence (C, B-flat, C) with an

accompanying lyric (“clap your hands”) was not eligible for

protection because it appeared commonly in music, rendering it

unoriginal.

57

Additionally, the lyric standing alone was too common a

phrase to render the otherwise unoriginal three-note sequence

original.

58

Looking to

McDonald v. Multimedia Entertainment, Inc

.,

59

the court observed that a claim of originality in a three-note sequence

taken from a television jingle was found “absurd.”

60

The

McDonald

court held that the sequence was too common in traditional western

music to be original; thus, it was unprotectable.

61

The second route to commonality that the court explained was

paved with generic compositional techniques. The court pointed to

Intersong-USA v. CBS, Inc

.,

62

in which the song’s descending step

motive, like the one in “Twinkle, Twinkle Little Star,” was deemed

too commonly used as a compositional device to be original; thus, it

was unprotectable.

63

Still, the district court noted that there have

been some findings of protectability for short sequences of notes.

64

The court explained that findings of originality for short

compositional sequences also generally occur along two routes:

samples involving greater than three notes and samples involving

53

.Id

.

54

.Newton

, 204 F. Supp. 2d at 1253

.

55. No. 00 Civ 4022 (DC), 2002 WL 287786 (S.D.N.Y. Feb. 27, 2002).

56.

Newton

, 204 F. Supp. 2d at 1253.

57.

Jean

, 2002 WL 287786 at 6-7.

58

.Id

.

59. 20 U.S.P.Q.2d 1372, 1991 WL 311921 (S.D.N.Y. 1991).

60.

Newton

, 204 F. Supp. 2d at 1253.

61. 1991 WL 311921 at 4.

62. 757 F. Supp. 274 (S.D.N.Y. 1991).

63

.Id

. at 282.

64

.Newton

, 204 F. Supp. 2d at 1254.

2003]

N

EWTON V

. D

IAMOND

131

unusual words and/or sounds.

65

Following the first route, the court

pointed to the finding of protectability in

Baxter v. MCA, Inc

..

66

There, the defendant had used the opening six notes of the plaintiff’s

composition to create the theme to the movie “E.T.” Yet, the court

observed that where sequences of less than six notes have been found

to be protectable, qualitative factors, such as: accompanying lyrics;

the heart of the composition; repetitive sequences or lyrics; and/or

common characteristics to both the composition and sound recording

have also been present.

67

Along the second route to originality, the court refuted the

plaintiff’s reliance on

Tin Pan Apple, Inc. v. Miller Brewing Co

.

68

as

supporting protectability for a few words or sounds.

69

Noting that the

defendant in

Tin Pan Apple

copied the words “hugga-hugga” and

“brrr,” the court did not find blanket support but, instead, a

distinguishing factor. The words used in

Tin Pan Apple

were unusual

and, by nature, unusual words and sounds are more distinctive than a

few generic notes.

70

After running the three-note “Choir” sequence through this dual

analysis looking for characteristics of either commonality or

originality, the court held that sample taken by the Beastie Boys is

unprotectable.

71

Here, the evidence showed that the three-note

sequence—C, D-flat, C—was a simple and common building block

extensively employed in twentieth century music by major composers,

especially in the decades preceding Mr. Newton’s use. Moreover, the

generic vocalization device had been recognized in academic

literature before the plaintiff adopted it for his composition, and it

had also been used in several compositions pre-dating the plaintiff’s

song. Consequently, as a matter of law, the court found neither the

three-note sequence nor the vocalization technique, or their

combination, sufficiently original to warrant protection.

72

65.

Id

.

66. 812 F.2d 421 (9th Cir. 1987).

67.

Newton

, 204 F. Supp. 2d at 1254.

68. 30 U.S.P.Q.2d 1791, 1994 WL 62360 (S.D.N.Y. 1994).

69

.See

Newton

, 204 F.Supp.2d at 1254.

70

.Id

.

71

.Id

. at 1254-55.

72

.Id

. at 1255.

132 H

ASTINGS

C

OMM

/E

NT

L.J. [26: 119

2. Doctrine of

De Minimis

Use

73

Although the district court could have been content with

extinguishing the action based on its preliminary determination that

the sampled portion of plaintiff’s composition was not protectable as

a matter of law, it provided an alternate ground for granting the

defendant’s motion for summary judgment. The court determined

that even if the three-note segment of Mr. Newton’s composition had

been found to be protectable, the doctrine of

de minimis

use would

apply to make the Beastie Boys’ sampling of it non-actionable as a

matter of law; thus, they would not be liable for copyright

infringement.

74

The court’s analysis explained that

de minimis

use operates to

prevent a finding of substantial similarity, a requirement for

actionable copying.

75

To explain the standard for

de minimis

use, the

court made reference to three cases:

Sandoval v. New Line Cinema

Corp

.;

76

Jean v. Bug Music, Inc

.;

77

and

Fisher v. Dees

.

78

First, the court

referred to

Sandoval

for the rule that to establish

de minimis

use, “the

alleged infringer must demonstrate that the copying of the protected

material is so trivial ‘as to fall below the quantitative threshold of

substantial similarity.’”

79

Referring to

Jean

, the court noted that

substantial similarity will not be found if only a small, common phrase

is copied, unless the copied portion is especially unique or

qualitatively important.

80

Finally, citing

Fisher

, the court stated that

copying is

de minimis

“if the average audience would not recognize

the misappropriation.”

81

Identifying the practice of digital sampling as involving

fragmented literal similarity,

82

the court stated that the general

approach among courts in analyzing

de minimis

use is to consider

both quantitative and qualitative factors.

83

Consequently, even if the

73. To more clearly follow the district court’s analysis throughout this section, it may

be helpful to refer to Diagram #4 in the Appendix,

infra

.

74.

Newton

, 204 F. Supp. 2d at 1256, 1260.

75

.Id

. at 1256-57.

76. 147 F.3d 215 (2d Cir. 1998).

77

.Jean

, 2002 WL 287786.

78. 794 F.2d 432 (9th Cir. 1986).

79. Newton, 204 F.Supp.2d at 1256.

80

.Id

. at 1256-57.

81

.Id

. at 1257.

82

.Id

. (citing N

IMMER ON

C

OPYRIGHT

§ 13.03 [A][2]).

83

.Id

. (citing N

IMMER ON

C

OPYRIGHT

§ 13.03[A][2]). Notably, the Court does not

cite to any particular cases for this proposition. Further, it is also important to note that

2003]

N

EWTON V

. D

IAMOND

133

amount copied is quantitatively trivial, the threshold of substantial

similarity may still be crossed if the portion used by the defendant is

especially unique or important.

84

The court explained that

quantitative and qualitative analyses focus solely upon the segment’s

significance to the plaintiff’s work, not the defendant’s use of it.

85

Therefore, the court stated that the quantitative or qualitative

importance the portion sampled possesses in the defendant’s new

song is irrelevant.

86

Here, the portion sampled by the Beastie Boys was only 2-

percent of “Choir.” Moreover, the three-note sequence appears only

once within “Choir.” Upon finding this to be quantitatively trivial in

relation to “Choir” as a whole, the court announced that the

plaintiff’s only chance for the sample to cross the threshold of

substantial similarity was via qualitative factors.

87

Although the court recognized that some segments of music may

be qualitatively important even standing alone, it reminded the

parties that—similar to the protectability analysis—what is at issue in

the

de minimis

use analysis is not whether the average listener might

recognize the segment as taken from the sound recording. Instead, it

is whether the average listener might recognize—from a performance

of the composition as written—the plaintiff’s musical composition as

the underlying source.

88

Here, even though the defendants conceded

they took “the best bit of ‘Choir,’” the court found that testimony

referred to the distinctiveness of the performance, not the

composition.

89

Further, the court again noted that in regards to

de

minimis

use, just as in the analysis of originality, the short

compositional sequences that have survived summary judgment have

involved: more than three notes; accompanying lyrics; the heart of

musical compositions; repetitive sequences; and/or sequences that

appear in both the composition and sound recording.

90

Finding none

of these factors present, the court stated that neither the notes nor the

generic vocalization technique—or their combination—imparted any

distinctiveness to the six-second portion sampled by the Beastie

this section of the Nimmer treatise is a discussion of substantial similarity and not

specifically

de minimis

use, a hurdle within its quantitative component.

84

.

Newton, 204 F. Supp. 2d at 1257.

85

.Id

.

86

.Id

.

87

.Id

. at 1258.

88

.Id

.

89

. See Newton

, 204 F. Supp. 2d at 1258-59.

90

.Id

. at 1259.

134 H

ASTINGS

C

OMM

/E

NT

L.J. [26: 119

Boys.

91

Thus, the court held that the plaintiff failed to identify any

factors separate from those attributable to his unique performance

that rendered the three-note sequence qualitatively important to

“Choir.”

92

Consequently, as a matter of law, the digital sampling of

“Choir” by the Beastie Boys was non-infringing due to its

quantitatively and qualitatively trivial nature.

3. International Copyright Infringement and Limitation of Damages

As a result of its determination on the claim under U.S. law, the

court made short shrift of the international copyright infringement

claim. That claim failed as a matter of law because it depended upon

successfully proving that the defendants were liable for at least one

completed act of infringement within the United States.

93

Additionally, the court held that even if the plaintiff’s copyright

claims had not failed, Mr. Newton would have only been entitled to

damages accruing after April 9, 1998.

94

The court’s reasoning is three-

fold. First, beginning with the statute, 17 U.S.C. § 507(b) mandates

that the civil action commence within three years after the claim

accrues.

95

Second, a claim accrues when the act of infringement

actually occurs, not when consequent damages are suffered.

96

Finally,

the plaintiff’s right to damages is limited to those suffered during the

statutory period of limitations regardless of when they may have been

incurred.

97

Thus, since Mr. Newton did not file suit until April 9,

2001, any damages incurred between 1992 and April 9, 1998, were not

eligible for consideration.

98

V. Newton v. Diamond: The Court of Appeals Obscures a Clue

A. The Judgment

On April 7, 2003, Mr. Newton’s appeal of the district court’s

decision was argued and submitted to the Ninth Circuit Court of

Appeals. Seven months later, on November 4, 2003, Chief Judge

Mary M. Schroeder issued the majority opinion affirming the grant of

91

.Id

.

92

.Id

.

93

.Id

.

94

.Newton

, 240 F. Supp. 2d at 1260.

95

.Id

.

96

.Id

.

97

.Id

.

98

.Id

.

2003]

N

EWTON V

. D

IAMOND

135

summary judgment to the Beastie Boys.

99

However, the opinion was

not merely an echo of the decision below.

The court began its opinion by acknowledging the difficulty and

importance of the sampling issue.

100

Yet, despite its recognition of the

district court’s “scholarly opinion,” it announced that—since it was

not required to address each decisional ground relied upon by the

lower court—it was basing its decision solely on the ground of

de

minimis

use.

101

Consequently, the Ninth Circuit ignored the district

court’s primary ground of decision—that as a matter of law, the

sampled sequence of “Choir” lacked sufficient originality to merit

copyright protection. Rather than undertake a review of that

threshold issue, the Ninth Circuit made an implied reversal of the

district court’s protectability holding by

assuming

the sampled

sequence of the composition

is

sufficiently original to merit copyright

protection.

102

B. Analysis of the Court

⎯

The Doctrine of De Minimis Use

Just as the district court had done, the Ninth Circuit began its

de

minimis

use analysis by showing a relationship between

de minimis

use and substantial similarity centered upon the determination of

actionable copying.

103

The court explained that although substantial

similarity between the plaintiff’s and defendants’ works must exist for

unauthorized copying to be actionable, the legal maxim

de minimis

non curat lex

(“the law does not concern itself with trifles”)

recognizes the coordinate principle that trivial copying will not

constitute actionable infringement.

104

However, differing from the district court, the Ninth Circuit

relied solely upon a footnote in its 1986 opinion in

Fisher v. Dees

to

establish the standard for

de minimis

use.

105

There, the court stated

99.

Newton v. Diamond

, 349 F.3d 591, 592 (9th Cir. 2003).

100

.Id

. at 592.

101

.Id

. at 592, 594.

102

. See id

. at 594.

103

. See id

.

104

. See id

.

105

.Id

. Although the standard built by the district court also has flaws, the district

court relied on a broader array of cases,

Sandoval

being primary among them with

Fisher

being referred to last—arguably as an elaboration. Notably, while the district court began

on track with the Second Circuit’s

Ringgold

standard—as expressed via

Sandoval

—

ultimately, it suffers from the same flaws as the analysis of

de minimis

use in

Newton II

.

Therefore, since

de minimis

use was merely a secondary ground of decision in

Newton I

,

the flaws within its

de minimis

use analysis are reserved for discussion via the Ninth

Circuit’s sole ground for decision.

136 H

ASTINGS

C

OMM

/E

NT

L.J. [26: 119

that a taking is considered

de minimis

only if it is so meager and

fragmentary that the average audience would not recognize the

appropriation.

106

Acknowledging that

de minimis

use was rejected as

a

defense

107

in

Fisher

, the court explained that, in

Fisher

, it found that

the defendant’s successful fair use defense—grounded in parody—

precluded finding the use insubstantial or unrecognizable since a

parodist must “‘appropriate a

substantial enough

portion . . .

to evoke

recognition

.’”

108

Building from the

Fisher

standard, the

Newton II

court

enunciated a further link between the tests for substantial similarity

and

de minimis

use by pointing to their common usage of the average

audience, or ordinary observer, to determine infringement.

109

The

court then concluded that, “to say that a use is

de minimis

because no

audience would recognize the appropriation is thus to say that the

works are not substantially similar.”

110

Consequently, after performing

a brief filtering exercise, the Court arrived at what it deemed to be

“the nub” of the

de minimis

use inquiry: “whether the Beastie Boys’

unauthorized use of the composition . . . was

substantial enough

to

sustain an infringement action

.”

111

Thereafter, similar to the district court, the Ninth Circuit

identified digital sampling as a problem of fragmented literal

similarity and stated that its substantiality is determined by

considering the qualitative and quantitative importance of the copied

segment in relation to the plaintiff’s work as a whole.

112

Here, the

evidence showed that, quantitatively, the sample comprised only 2-

percent of Mr. Newton’s composition and appeared only once within

“Choir.” From the qualitative perspective, the court held that the

sample was no more significant than any other section of the

composition because, with the exception of two notes, the entire

composition was made up of notes separated merely by whole and

106.

Fisher

, 794 F.2d at 434 n.2.

107. Whether the doctrine of

de minimis

use constitutes a defense or an element of the

plaintiff’s prima facie case is an open question, which will be discussed in Part VI. B,

infra

.

108.

Newton

, 349 F.3d at 595 (citing

Fisher

, 794 F.2d at 434 n.2) (emphasis added).

109

.Id

. at 594.

110

.Id

.

111

.Id

. at 596 (emphasis added).

112

.Id

. (citing 4 N

IMMER ON

C

OPYRIGHT

§ 13.03 [A][2], at 13-47, 48, n. 97). Once

again, as mentioned in note 83, it is important to realize that this section of the Nimmer

treatise is a discussion of substantial similarity and not specifically

de minimis

use, a hurdle

within its quantitative component.

2003]

N

EWTON V

. D

IAMOND

137

half steps.

113

Moreover, the plaintiff’s expert had described the

sample as a simple neighboring tone figure.

Notably, agreeing with the district court that the particulars of a

defendant’s use are irrelevant, the Ninth Circuit never analyzed the

Beastie Boys’ use of the sample.

114

The court declined to consider the

defendants’ use, stating that a rule requiring it to do so would allow

unscrupulous defendants to copy large or qualitatively significant

portions of a work and escape liability by burying them under non-

infringing material—“

even where an average audience might recognize

the appropriation

.”

115

In this regard, the court seemed to forget (or

discard) the premise with which it began its analysis, its own

Fisher

standard.

Similar to

Newton I

, the

Newton II

court placed the burden of

clearing the hurdle of

de minimis

use upon the plaintiff. Thereafter,

finding the evidence insufficient, the court similarly held that the

plaintiff failed to demonstrate the sample’s quantitative or qualitative

significance.

116

Consequently, the court deemed that Mr. Newton was

in a weak position to argue the presence of substantial similarity

between the works, or that an average audience would recognize the

appropriation.

117

Ultimately, the court’s

de minimis

use analysis led it

to conclude that the Beastie Boys’ use of the sample was insufficient

to sustain a claim for copyright infringement of the “Choir”

composition.

118

VI. Reality Check

A. Which is the Path to Reasonable Determination?

Just as the shortest distance between two points is a straight line,

the surest path to reasonable predictability in the law is a

straightforward, non-circuitous legal analysis. As mentioned earlier,

what has been sorely needed is a path of reasonable determination by

which to escape the persistent legal uncertainty surrounding the

practice of digital sampling. So, did the

Newton

courts finally blaze

that trail—the district court in

Newton I

with its protectability

113

.Id

. at 597.

114

.Id

.

115

.Id

.

116

.Id

. at 597-98.

117

.Id

. at 598.

118

.Id

. (emphasis added).

138 H

ASTINGS

C

OMM

/E

NT

L.J. [26: 119

(originality) analysis and/or the court of appeals in

Newton II

with its

de minimis

use analysis?

Although the factual distinctions it made may initially appear to

be an

ad hoc

consolidation of previous judicial pronouncements, the

Newton I

court seems to have blazed the most straightforward trail of

legal analysis. Thus, this author believes, the

Newton I

approach

could have provided the music industry a path of reasonable

determination. At its most basic level, the

Newton

I

approach can be

described as entailing two steps: filtration

119

and an originality

determination. Notably, no matter what approach one pursues,

filtration must be performed to separate the unique performance

elements of the sound recording from an analysis of the composition.

Thus, the core of the

Newton

I

approach is that, once distilled, the

sample from the composition can be run through a protectability

analysis

120

via a series of relatively straightforward questions, such as:

(1) is the sample comprised of three notes or less and/or a generic

compositional technique; (2) does the sample contain either six notes

or more, or unusual words or sounds; and (3) if the sample is

comprised of less than six notes or generic compositional techniques,

does it also contain (a) accompanying lyrics, (b) the heart of the

composition, (c) a sequence or lyric that is repetitive within the

composition, and/or (d) a sequence that is identically expressed in

both the sound recording and the composition? While not hitching

posts, these questions could be viewed as guideposts to lawful

sampling, which had not been previously elucidated. Consequently, as

a threshold determination, the

Newton I

approach has the potential

advantage of extinguishing claims before the need to undertake more

elaborate analyses arises.

On the other hand, those following

Newton II

may get lost along

its circuitous route. To illustrate its confusing twists and turns, picture

the following: as you begin to travel down the

Newton II

path, you see

a road sign marking the path as “

de minimis

: use too meager and

fragmentary to evoke recognition.” A short distance away, you come

upon another sign marking the path as “substantial similarity: use not

substantial enough to sustain an infringement action.” Thus, you

begin to wonder what test you are to apply and what are its

components. Just then, you arrive at a three-pronged fork in the road.

The first path is marked “significance to the plaintiff’s work.” The

119. For a graphic depiction of the

Newton I

court’s performance of this exercise, see

Diagram # 2 in the Appendix,

infra

.

120. For a graphic depiction of the protectability (originality) analysis, see

Diagram # 3 in the Appendix,

infra

.

2003]

N

EWTON V

. D

IAMOND

139

second path is marked “defendant’s use of the work,” and the third

path is marked “comparison between the plaintiff’s and defendant’s

work.” However, upon glancing down each path, you notice that the

second and third paths are immediate dead-ends. Thus, the only path

for you to walk is the first. Setting out, you turn left to examine the

quantity of the use. Along here, the

Newton II

court has planted a

marker stating, “Please note: under

Fisher

, a successful fair use

defense will prevent you from finding insubstantial or unrecognizable

use.” Next, you turn to the right to examine the qualitative

significance of the copied segment. Once again you are met with dual

markers; side-by-side they instruct, “Watch out for recognizability”

and “Watch out for a sustainable infringement action.” Yet, upon

reaching the end of the path, a final sign blocking egress from the

summary judgment proceeding states: “Proceed to full trial of this

matter

only

upon finding a sustainable infringement action.”

So, was there any consideration of the enunciated

Fisher

“recognizability” factor or was it impliedly subsumed within the

substantial similarity analysis? Moreover, was this a path for

analyzing

de minimis

use or for performing a full substantial similarity

test? It seems that rather than blaze a trail of reasonable

determination, the

Newton II

court has created a conundrum of

de

minimis

use analysis.

B. The Conundrum of De Minimis Use Analysis

Newton II

highlights the problem that a clear standard for

de

minimis

use has not yet been settled upon in the courts.

121

While

there may have already been a few lingering questions surrounding

the concept,

Newton II

surely added to the list. Currently, it seems

the riddle must be solved by answering the following questions: (1)

what is the

de minimis

standard; (2) which party has the burden of

proof; (3) where does the fair use defense fit into the analysis; (4)

what is the proper consideration to be given to the qualitative nature

of the copied portion; (5) does the

de minimis

use analysis merely

provide the means by which to bypass the factfinder on the issue of

substantial similarity; and finally, (6) which works should be

considered: solely the plaintiff’s, solely the defendant’s, or both?

121. Recently, however, the Sixth Circuit issued an opinion in

Gordon v. Nextel

Comms

., 345 F.3d 922 (6th Cir. 2003), which seems to closely follow the

Ringgold

analysis

of

de minimis

use. The

Gordon

court’s analysis focused on the quantitative measure

including consideration of the observability of the copied work within the defendant’s new

work. Notably, the

Gordon

court makes absolutely no mention of a qualitative factor

within its

de minimis

use analysis.

140 H

ASTINGS

C

OMM

/E

NT

L.J. [26: 119

First, what is the

de minimis

use standard? In

Fisher

, the Ninth

Circuit defined it as use “so meager and fragmentary that the average

audience would not recognize the appropriation.”

122

However,

subsequent to

Fisher

, the Second Circuit’s 1997 decision in

Ringgold

v. Black Entertainment Television, Inc

.

123

became the polestar of

de

minimis

use analysis.

Ringgold

formulated

de minimis

use as a

threshold determination on the way to a substantial similarity

analysis.

124

The

Ringgold

court explained that while substantial

similarity has both quantitative and qualitative components, the

de

minimis

concept is relevant to the quantitative component.

125

In this

regard the court stated, “since ‘substantial similarity,’ properly

understood, includes a quantitative component, it becomes apparent

why the concept of

de minimis

is relevant.”

126

Additionally,

Ringgold

established an observability test within

the

de minimis

use analysis.

127

Under the facts presented in

Ringgold

,

that observability test was applied to visual works. There,

observability was measured via characteristics of the defendant’s

work, such as: the length of time the copied portion is observable, the

focus, lighting, camera angles, and prominence.

128

Yet, these

characteristics seem to measure not only observability but also

recognizability. Thus, the observability test within

Ringgold

appears

to echo

Fisher

’s recognizability requirement.

129

Indeed, the

Ringgold

court found:

[I]n some circumstances a visual work . . . might ultimately be

filmed at such a distance and so out of focus that a typical program

viewer would not discern [the] effect that the work of art

contributes to the [new work]. But that is not this case. The

painting component is

recognizable

as a painting . . . .

130

Consequently, after

Fisher

and

Ringgold

, the

de minimis

use standard

could reasonably be understood as being comprised of two

122. 794 F.2d at 434 n.2.

123. 126 F.3d 70 (2d Cir. 1997).

124

. See id

. at 74.

125

.Id

.

126

.Id

. at 75.

127

.Id

.

128

.Id

.

129. Although, this would not be a direct echo since

Ringgold

never mentions or cites

to

Fisher

.

130

.

126 F.3d at 77.

2003]

N

EWTON V

. D

IAMOND

141

considerations: (1) quantitatively trivial portions of the plaintiff’s

work, or (2) unrecognizable use within the defendant’s work.

Second, which party has the burden of proof? Although the

defendants in both

Fisher

and

Ringgold

made the express assertion

that their use of the copyrighted work was

de minimis

, neither court

explicitly addressed the burden of proof on the matter. However, in

1998 the Second Circuit concisely reiterated the

Ringgold

standard in

Sandoval v. New Line Cinema Corp

.

131

and, while doing so, placed the

burden of proof upon the defendant.

132

The

Sandoval

court declared,

“the alleged infringer must demonstrate that the copying of the

protected material is so trivial ‘as to fall below the quantitative

threshold of substantial similarity’.”

133

Yet, in

Newton I

and

II

the

burden of proof was clearly placed upon the plaintiff.

134

Although the Nimmer treatise refers to

de minimis

use as a

defense in a few instances,

135

it does not discuss the burden of proof

on this issue. Yet, its nature as a threshold determination to be made

before the factfinder is bothered to undertake a full substantial

similarity analysis

136

would intimate that it should be characterized as

part of the plaintiff’s prima facie case, thus, burdening the plaintiff.

Further, even if

de minimis

use is properly characterized as an

affirmative defense, the question still might arise as to whether

de

minimis

use can be considered an equitable rule of reason, allowing

the court discretion to shift the burden back to the plaintiff, as

occurred under the analysis of the fourth fair use factor in

Sony Corp.

of America v. Universal City Studios, Inc

.

137

Third, where (if anywhere) does the fair use defense fit into the

de minimis

use analysis?

Ringgold

established that the

de minimis

use

analysis is inappropriate to the issue of fair use;

138

thus, implicitly, fair

use is also inappropriate to the

de minimis

use analysis. Indeed, the

Ringgold

court advised that where the allegedly infringing work

makes a quantitatively trivial use of a copyrighted work, “it makes

more sense to reject the claim on that basis and find no infringement,

131. 147 F.3d 215 (2d Cir. 1998).

132

.Id

. at 217.

133

.Id

.

134.

Newton I

, 204 F. Supp. 2d at 1258-59;

Newton II

, 349 F.3d at 597-98.

135. M

ELVILLE

B. N

IMMER

& D

AVID

N

IMMER

, N

IMMER ON

C

OPYRIGHT

§ 8.01[G],

8-24, 25, 26 (Matthew Bender & Co., Inc. 2003) (1963).

136. Remember, “the law does not concern itself with trifles” (

de minimis non curat

lex

). Arguably, this could be translated into more blunt phrasing, such as: “don’t bother

the court to exert its resources in putting trivial concerns through elaborate legal analysis.”

137. 464 U.S. 417, 451 (1984).

138. 126 F.3d at 75-76.

142 H

ASTINGS

C

OMM

/E

NT

L.J. [26: 119

rather than undertake an elaborate fair use analysis in order to

uphold a defense.”

139

The

Sandoval

court echoed this advice by

holding that it was error for the lower court to have resolved the fair

use claim without first determining whether the alleged infringement

was

de minimis

.

140

So, although a defendant will often present claims

of

de minimis

use and fair use as tandem defenses, a court will not

properly reach the fair use defense until it has resolved the

de minimis

use question. Consequently,

Newton II

’s resurrection of

Fisher

’s

consideration of fair use as precluding a finding of

de minimis

use

appears to be a red herring.

Fourth, what is the proper consideration to be given to the

qualitative nature of the copied portion? When refuting substantial

similarity is made the thrust of the

de minimis

use analysis, it presents

the danger that substantial similarity’s quantitative and qualitative

factors will dominate the process. Moreover, making qualitative

significance a primary factor alongside the quantitative measure

creates the risk that

de minimis

use analysis will, mistakenly, be

equated with the third factor of fair use—the amount and

substantiality of the use in relation to the copyrighted work as a

whole. As mentioned earlier, this would be inappropriate, especially

since

Ringgold

noted the distinction that the third fair use factor

operates along a continuum for which there is no precise threshold.

141

However, a qualitative factor may have value to

de minimis

use

analysis as a sort of “safety- valve” feature—a “double-check.”

142

Judge Graber in his dissent to

Newton II

validly reminds us that,

“even passages with relatively few notes may be qualitatively

significant. The opening melody of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony is

relatively simple and features only four notes, but it certainly is

compositionally distinctive and recognizable.”

143

A qualitative

consideration also seems compatible with the observability (or

recognizability) test, especially since the heart of a copyrighted work

will be inherently more recognizable even if quantitatively smaller

than other parts of the copyrighted work.

Although, a question looms over a

de minimis

use qualitative

factor, which is: if a three-note sequence has already been found

sufficiently original to be protected by copyright law—how much

139

.Id

. at 76.

140. 147 F.3d at 217.

141. 126 F.3d at 76.

142. This proposition finds support in the Nimmer treatise.

See

N

IMMER

,

supra

note

135, § 13.03[A][2] at 13-47.

143.

Newton v. Diamond

, 349 F.3d 591, 598-99 (9th Cir. 2003) (Graber, J., dissenting).

2003]

N

EWTON V

. D

IAMOND

143

more original, or distinctive, does it need to be to clear the hurdle of

de minimis

use?

Newton I

suggests that for quantitatively trivial

sequences to survive summary judgment on

de minimis

use, they must

be somewhat larger than Newton’s three notes and involve either: (a)

accompanying lyrics, (b) the heart of the composition, (c) notes or

lyrics that repeat within the copyrighted work, and/or (d) sequences

that are identically expressed in both the composition and the sound

recording.

144

Newton II

suggests that the plaintiff needs to show that

the copied segment is more significant than any of the other segments

in the copyrighted work.

145

In regards to “Choir,” the

Newton II

court found: “Qualitatively,

this section of the composition is no more significant than any other

section. Indeed, with the exception of two notes, the entirety of the

scored portions of “Choir” consists of notes separated by whole- and

half-steps from their neighbors.”

146

Here, it may be appropriate to

recall the warning given by Justice Holmes in

Bleistein v. Donaldson

Lithographing Co

.:

147

“It would be a dangerous undertaking for

persons trained only to the law to constitute themselves final judges

of the worth of [expressive works], outside of the narrowest and most

obvious limits.”

148

Notably, both

Newton

courts failed to consider the

fact that the sampled sequence is the opening of “Choir” and unique

within the composition rather than repetitive, which may actually

enhance its distinctiveness rather than diminish it. Thus, even though

a qualitative factor may hold value for

de minimis

use analysis, a

court must exercise caution in its application.

Fifth, does the

de minimis

use analysis simply provide the means

by which to bypass the factfinder on the issue of substantial

similarity?

149

In other words, when considering

de minimis non curat

lex

during a summary judgment proceeding, should courts be making

a black and white choice between trivial, non-recognizable use (a

matter of law) and substantial similarity (a question for the

factfinder)?

150

Or should they, instead, decide whether the use of a

copied segment rises above a trivial, non-recognizable use to cross

144. 204 F. Supp. 2d at 1259.

145.

Newton

, 349 F.3d at 597.

146

.Id

.

147. 188 U.S. 239, 251 (1903).

148

.Id

.

149. Could this be substantial similarity analysis in the proverbial “sheep’s clothing?”

150. The relationship between substantial similarity and

de minimis

use seems to have

caused semantic confusion, which in turn has led to legal confusion in regards to its

analysis.

144 H

ASTINGS

C

OMM

/E

NT

L.J. [26: 119

into a gray area where reasonable minds may differ, presenting a

genuine issue of material fact regarding substantial similarity reserved

for the factfinder. This author believes it should be the latter, for

although there is a relationship between trivial use and substantial

similarity, if it is formulated as simply a black and white distinction—

with trivial use merely being the negative of substantial similarity—

courts run the risk of inadvertently eliminating the factfinder from the

determination of substantial similarity. Judge Graber’s dissent in

Newton II

demonstrates this possibility when he states:

[T]he composition, standing alone, is distinctive enough for a jury

reasonably to conclude that an average audience would recognize

the appropriation of the sampled segment . . . Because Newton has

presented evidence establishing that reasonable ears differ over the

qualitative significance of the composition of the sampled material,

summary judgment is inappropriate in this case.

151

Sixth, and finally, which work should be considered—solely the

plaintiff’s, solely the defendant’s, or both? In general, the answer is

both. However, as seems typical of

de minimis

use analysis, that

answer is not as straightforward as it appears on the surface.

Quantitatively,

Newton I

and

II

appear at first glance to correctly

state that the significance of the copied sequence in relation to the

defendants’ work is irrelevant and only the plaintiff’s copyrighted

work should be considered. Yet, this is likely the result of the

aforementioned ease with which the

de minimis

use analysis may be

confused with the third factor of fair use.

Indeed,

Ringgold

directs us to consider not only the quantitative

significance of the copied portion in relation to the plaintiff’s work,

but also the quantitative significance of the copied portion in relation

to the defendants’ work. To notice this directive, one need only look

to

Ringgold

’s observability test. Although “observability” may seem

to connote some sort of qualitative consideration,

Ringgold

deems it a

quantitative consideration.

152

In this regard,

Ringgold

states, “the

quantitative component of substantial similarity also concerns the

observability of the copied work [including] the length of time the

copied work is observable in the allegedly infringing work.”

153

In

Ringgold

, the court examined evidence regarding the

durational aspects of the defendant’s use, noting that all nine

151.

Newton

, 349 F.3d at 598, 600 (Graber, J., dissenting).

152. 126 F.3d at 75.

153

.Id

.

2003]

N

EWTON V

. D

IAMOND

145

instances in which the copyrighted work appeared to any degree

amounted to an aggregate duration of 26.75 seconds.

154

Further, the

court found that the repetitive effect of such use reinforced the effect

of its initial appearance. Thus, the court held:

From the standpoint of a quantitative assessment of the segments,

the principal four-to-five-second segment in which almost all of the

poster is clearly visible, albeit in less than perfect focus, reenforced

[sic] by the briefer segments in which smaller portions are visible,

all totaling 26 to 27 seconds, are not

de minimis

copying.

155

Notably, in discussing fragmented literal similarity, the Nimmer

treatise states; “The practice of digitally sampling prior music to use

in a new composition should not be subject to any special analysis: to

the extent that the resulting product is substantially similar to the

sampled original, liability should result.”

156

Therefore, given the

symbiotic relationship between the concepts of substantial similarity

and

de minimis

use, it is doubtful that—given

Ringgold

’s focus on

visual works—a different quantitative approach should pertain to

other types of works, such as compositions and sound recordings.

Qualitatively,

Newton I

and

II

also deem the defendants’ work to