Angela M. Antonelli

Research Professor and Executive Director

Policy Report 20-02

December 2020

What are the Potential Benets of

Universal Access to Retirement Savings?

An Analysis of National Options to Expand Coverage

In conjunction with

Support for this research was provided by

economics | strategy | insight

The Center for Retirement Initiatives (CRI) at Georgetown University is a research center of the McCourt School

of Public Policy, one of the top-ranked public policy programs in the nation. Through its academic reputation

and ability to engage with policymakers, business leaders, and other stakeholders, the McCourt School attracts

world-class scholars and students who have become leaders in the public, private, and nonprot sectors. The

CRI is dedicated to:

• Strengthening retirement security by expanding access and coverage for the private sector workforce;

• Providing thought leadership and developing innovative new approaches to retirement savings, investment,

and lifetime income;

• Serving as a trusted policy advisor to federal, state, and local policymakers and stakeholders.

600 New Jersey Avenue, NW, 4th Floor

Washington, D.C. 20001

202-687-4901 · https://cri.georgetown.edu/

About the Center for Retirement Initiatives (CRI)

Econsult Solutions, Inc. provides businesses and public policymakers with consulting services in urban

economics, real estate, transportation, public infrastructure, public policy and nance, community and

neighborhood development, planning, and thought leadership, as well as expert witness services for litigation

support. Our technical expertise ranges from Big Data analysis to GIS-based spatial analytics, sophisticated

benet-cost analysis, and pro forma-based project feasibility analysis.

ESI’s government and public policy practice combines rigorous analytical capabilities with a depth of experience

to help evaluate and design eective public policies and benchmark and recommend sound governance

practices. ESI has assisted policymakers at multiple levels of government to design and evaluate programs that

help citizens increase their economic security.

1435 Walnut Street, 4th Floor

Philadelphia, PA 19102

215-717-2777 · https://econsultsolutions.com/

About Econsult Solutions, Inc. (ESI)

The Berggruen Institute’s mission is to develop foundational ideas and shape political, economic, and social

institutions for the 21st century. By providing critical analysis using an outwardly expansive and purposeful

network, we bring together some of the best minds and most-authoritative voices from across cultural and

political boundaries to explore fundamental questions of our time. Our objective is to have an enduring impact

on the progress and direction of societies around the world. To date, projects inaugurated at the Berggruen

Institute have helped develop a youth jobs plan for Europe; fostered a more-open and constructive dialogue

between Chinese leadership and the West; strengthened the ballot initiative process in California; and launched

Noema, a new publication that brings thought leaders from around the world together to share ideas. In addition,

the Berggruen Prize, a $1 million award, is conferred annually by an independent jury to a thinker whose ideas

are shaping human self-understanding to advance humankind.

Bradbury Building

304 S. Broadway, Suite 500

Los Angeles, CA 90013

310-550-70983 · https://www.berggruen.org/

About the Berggruen Institute

© 2020, Georgetown University

All Rights Reserved

iii

What are the Potential Benets of Universal Access to Retirement Savings?© 2020 Georgetown University Center for Retirment Initiatives

Acknowledgments

The Georgetown University Center for Retirement Initiatives (CRI) is grateful to the Berggruen Institute for

the generous support that has made this report possible, and to Econsult Solutions, Inc. (ESI) for a research

collaboration that has allowed the Center’s vision for this report to become a reality. We are honored to partner

with these organizations to advance our shared mission of strengthening retirement security and promoting the

expansion of access to savings options for millions of American workers who currently lack such access.

The CRI also thanks Courtney Eccles, Yakov Feygin, J. Mark Iwry, David John, Michael Kreps, and David Morse

for their helpful consultations and feedback in the preparation of this report. The ndings and conclusions

expressed are solely those of the author and do not represent those of the Berggruen Institute, Econsult

Solutions, Inc., or the Center for Retirement Initiatives.

Suggested Report Citation

Antonelli (2020). What are the Potential Benets of Universal Access to Retirement Savings?

Georgetown University Center for Retirement Initiatives in conjunction with Econsult Solutions, Inc.

© 2020, Georgetown University

All Rights Reserved

iv

What are the Potential Benets of Universal Access to Retirement Savings? © 2020 Georgetown University Center for Retirment Initiatives

Contents

Executive Summary . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1

1. Closing the Signicant Gaps in Access to Retirement Savings . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 9

1.1 Signicant Gaps Remain in Access to Retirement Savings . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 9

Gaps in Private Sector Access Disproportionately Impact Certain Groups . . . . . . . . . . 9

Too Many Have Little Saved for Retirement. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10

An Aging Population Increases the Urgency . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11

1.2 Policy Approaches Taken to Close the Access Gap . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 12

International Models Toward Universal Access . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 13

US Eorts Have Fallen Short of Universal Access . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14

National Proposals for Universal Access . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 17

Analyzing How Dierent Design Options Aect Access and Savings . . . . . . . . . . . . . 19

2. Analyzing the Potential Benets of National Universal Access to Retirement Savings Options . . . 21

2.1 Participation, Savings, and Assets under a Baseline Auto-IRA Scenario . . . . . . . . . . . 21

Starting Sooner and Saving Longer Signicantly Improves Retirement Outcomes . . . . . . . 21

How a Payroll Deduction Auto-IRA Expands Access and Builds Savings . . . . . . . . . . . 23

Protecting Savings is Critical to Asset Growth and Retirement Income . . . . . . . . . . . . 27

2.2 Policy Choices Have Impacts on Coverage and Savings . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 29

Thresholds for Employer Participation Dictate the Remaining Access Gap . . . . . . . . . . 29

Voluntary Employer Contributions Can Increase Participant Savings . . . . . . . . . . . . . 31

Required Employer Contributions Can Increase Employee Returns — with Economic Trade-os . . 33

Analyzing How Policy Choices Aect Participation, Savings, and Asset Building . . . . . . . . 34

3. Long-Term National Impacts from Increased Savings . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 38

3.1 Increased Economic Growth and Tax Revenue . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 38

Enhancing Economic Productivity and Accelerating Growth . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 38

Increased Tax Revenues from Economic Growth . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 40

3.2 Assessing the Impact on Federal Benet Programs . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 41

Federal Benet Program Spending is Anticipated to Rise Signicantly . . . . . . . . . . . . 41

Increasing Retiree Incomes Can Reduce Program Expenditures . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 42

Conclusion . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 44

Endnotes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 45

1

What are the Potential Benets of Universal Access to Retirement Savings?© 2020 Georgetown University Center for Retirment Initiatives

Part 1: Closing the Signicant Gaps in

Access to Retirement Savings

Workers in the United States are being asked to

take responsibility for their nancial well-being in

retirement now more than ever. What used to be

considered the foundation for building a secure

retirement — Social Security, employer-provided

pensions, and personal savings — has been

weakening for decades as traditional dened

benet (DB) pension plans have been replaced by

a dened contribution (DC) system of savings that

was originally meant to supplement, not replace,

traditional pensions.

Most employers today that have retirement plans

only oer DC options. This shift over time from

employer-provided pensions to DC plans has put

greater responsibility on workers to make complex

savings and investment decisions that will aect the

amount of money available in retirement. Americans

who have access to retirement savings accounts

often do not save enough to maintain their quality of

life in retirement.

Making matters worse, while employer-sponsored

retirement plans have become the primary way private

sector workers build retirement savings, employers in

the United States are not required to oer retirement

savings plans. Today, there are an estimated 57

million private sector workers (46%) who do not have

access to a plan through the workplace (see Figure

ES.1). These access gaps are inequitably distributed,

aecting more small businesses, and with larger gaps

among lower-income workers, younger workers,

minorities, and women.

For several years, there have been discussions and

proposals in the United States about how to expand

access to ways to save for retirement. If we look

internationally, there is usually little debate about

the value of universal access to retirement savings,

and several countries require employers to provide a

retirement savings option for their employees. With

all workers covered, dierences can be found in

the design of such options to achieve the levels of

savings needed to boost income in retirement.

Universal access to retirement savings options

would give all workers the opportunity to save, and

evidence from other countries, from individual states,

and from private sector plans suggests that many

would begin to do so, especially when encouraged

using default options, such as automatic enrollment.

Workers would benet from the increased savings

and the additional income in retirement. At the

same time, the economy benets from stronger

savings, investment, and economic growth, and the

nation benets from a reduction in scal pressures

to support an aging population lacking sucient

retirement income.

An Aging Population Increases the Urgency

This lack of access to employer-sponsored

retirement savings plans takes on greater urgency

due to the aging of the US population. Senior

households are growing signicantly in number and

as a share of the population, with the “dependency

ratio” projected to fall from its historic norms of

almost four working age households for each elderly

household to a ratio of closer to two to one (see

Executive Summary

67.3M57.3M

46%

GAP

Figure ES.1: More than 57 Million Employees

Lack Access to a Retirement Savings Plan in their

Workplace (2020)

ESI analysis of Census Bureau Current Population Survey

and BLS National Compensation Survey Data.

Access to coverage at work

Coverage access gap

124.6 M

Private Sector Employees

2

© 2020 Georgetown University Center for Retirment InitiativesWhat are the Potential Benets of Universal Access to Retirement Savings?

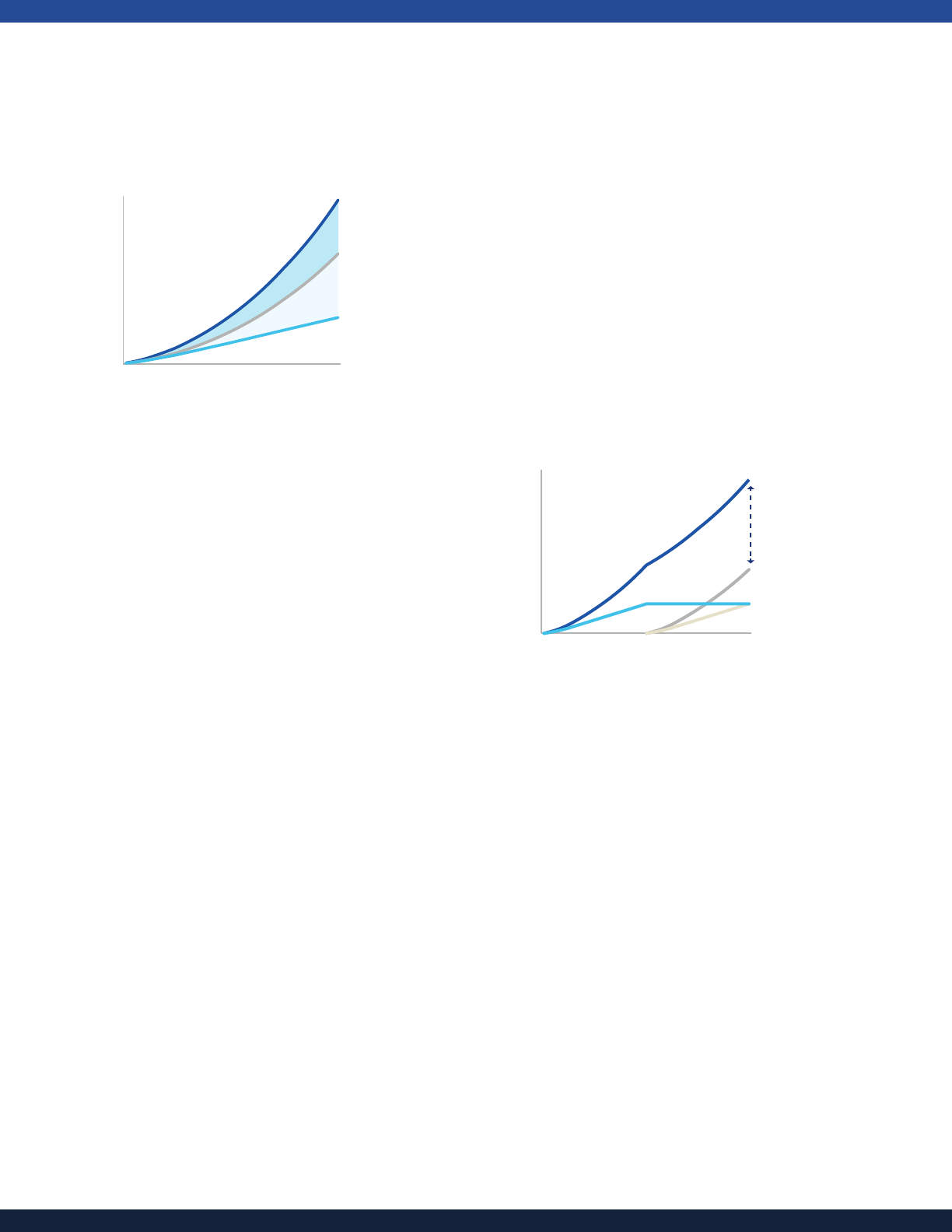

Figure ES.2). Since working age households are

the primary contributors to the tax base, this falling

dependency ratio creates greater scal pressures as

the demand for benet programs increases.

This shift in population composition also underscores

the importance of enabling younger generations

like millennials and Gen Z (which will cover the

prime working ages of 30–60 by 2040) to have

opportunities during their crucial savings years to

build resources to support their nancial futures.

Policy Approaches Taken to Close the Access

Gap

Federal policymakers in the United States have

developed and started to implement reforms

intended to close the gap in private sector retirement

savings access, encourage savings, and strengthen

the retirement readiness of workers. International and

state examples provide models to achieve universal

access that can do much more to expand coverage

and savings levels.

International Models Toward Universal Access

Eorts to expand access, participation, and savings

are not unique to the US. Many countries have

adopted a mix of public and private models to move

toward universal access, often requiring employer

participation and/or the automatic enrollment of

workers who can choose to opt out, that have resulted

in signicant coverage and savings levels. Established

programs in countries like Australia, New Zealand

and the United Kingdom have gained signicant scale

over time, demonstrating the sustainability of these

types of programs to help participants save more for

retirement (see Figure ES.3).

US Eorts Have Fallen Short of Universal Access

Several legislative proposals intended to achieve

national universal access, modeled on international

experience and the innovative design ideas of policy

experts, have been introduced in Congress for more

than a decade and as recently as 2019. To date,

these proposals have not had sucient support to

advance.

In the absence of national action, some states have

started to adopt innovative public-private partnership

models to expand access to their workers. A few

of these new state programs have adopted and

launched an Auto-IRA model, which requires

employers that do not already oer their workers

a retirement savings plan to automatically enroll

their workers in the state program to begin to save

unless the worker opts out. These state programs

are currently providing many employers and their

employees with new ways to save, and the number

of new accounts and assets is now growing at a

steady pace (see Figure ES.4).

1

Recent Congressional action, such as the SECURE

Act (P.L. 116-94), intended to expand the adoption

Figure ES.3: Employer-Based International

Savings Programs

Australia Superannuation Guarantee – 16.7 million

participants

Requires employers to contribute 9.5% of an eligible

employee’s earnings to a retirement savings account.

KiwiSaver – 3 million participants

Workers auto enrolled (can opt out) to contribute ≥

3% of earnings + 3% employer match and a tax credit

contribution.

UK NEST – 9 million participants

Uncovered workers auto enrolled (can opt out) at default

contribution levels of 5% employee + 3% employer.

Figure ES.2: Falling Ratios of Working-Age to

Elderly Households Create Fiscal Pressure

ESI analysis of US Census Bureau data

and University of Virginia Population Projections.

3.9

3.8

3.6

3.6

3.8

3.9

3.7

3.2

2.8

2.5

2.3

2.3

2.3

2040203520302025202020152010200520001995199019851980

3

© 2020 Georgetown University Center for Retirment Initiatives What are the Potential Benets of Universal Access to Retirement Savings?

and improve the design of dened contribution

plans, is another positive step.

2

While these

individual state programs and recent incremental

federal reforms are benecial, these initiatives are

unlikely to achieve a signicant national expansion

of coverage and savings.

Part 2: Analyzing the Potential Benets of

National Universal Access to Retirement

Savings Options

The experience of well-established international

programs and, more recently, the experience of

individual state retirement savings programs point

to the need for serious consideration of national

universal access to retirement savings options to

expand the number of employers who oer their

workers a way to save for retirement. Such options

would require certain employers to provide their

employees with access to a savings option, while

retaining the ability of employees to choose to opt

out of saving. A national, universal access approach

to retirement savings would substantially increase

participation and savings levels, particularly among

low- and middle-income workers.

Drawing on a range of state, national, and

international programs and proposals, this study

analyzes the potential impacts for access, savings,

and retirement security of a “baseline” national

universal access retirement savings option, and

the relative impacts on coverage and savings of

a number of potential policy variations from this

baseline.

The baseline model analyzed is an automatic

enrollment payroll deduction individual retirement

account (Auto-IRA) that is similar to a model

currently being implemented by some states and

included in legislative proposals introduced in

Congress. This streamlined and low-cost approach

uses automatic enrollment, default savings, and

auto-escalation mechanisms, which encourage

participation and savings while leaving participants

with full control over their participation and

contribution levels. In this model, all contributions

are made by the employee with no employer

contribution.

This model is used as the baseline because it is

comprehensive in requiring workplace access,

and simple in its structure and implementation.

Alternatives to this baseline are then analyzed by

adjusting several design features, including:

• Varying the type of savings account used

between a payroll deduction Roth IRA and

Roth 401(k), factoring in dierences in the

administrative requirements and the costs of

such accounts;

• Adding employer size and age thresholds,

exempting the smallest and youngest

businesses from the requirement to provide their

employees with access to retirement savings;

• Including a voluntary employer contribution,

as permitted in 401(k) accounts to give

businesses the discretion to contribute to

employee accounts; and

• Requiring an employer contribution by

adding a new requirement for employers to

provide contributions into an employee’s 401(k)

account, improving the return on investment

for savers but generating additional economic

implications for businesses and workers.

Figure ES.4: Recently Launched State Auto-IRA

Programs

OregonSaves – Launched 2017

Auto-IRA program required for all employers without an

existing qualied plan, 5% default employee contribution

with auto-escalation, and no employer match permitted.

Illinois Secure Choice – Launched 2018

Auto-IRA program required for employers with ≥ 25

employees without an existing qualied plan, 5% default

employee contribution, and no employer match permitted.

CalSavers – Launched 2019

Auto-IRA program required for employers with ≥ 5

employees without an existing qualied plan, 5% default

employee contribution with auto-escalation, and no

employer match permitted.

4

© 2020 Georgetown University Center for Retirment InitiativesWhat are the Potential Benets of Universal Access to Retirement Savings? © 2020 Georgetown University Center for Retirment Initiatives

These policy variations are applied to generate four

modeled scenarios (see Figure ES.5). Most policy

features are retained across the scenarios to isolate

the impact of only those features that have been

adjusted on access, savings, and retirement security

for workers currently lacking access. Modeling and

discussion within this analysis reects the trade-os

among these objectives, the potential challenges for

dierent groups (such as employers and employees),

and some of the technical considerations inherent

in policy eorts of this scale. Policy options are

analyzed through the year 2040, assuming adoption

of a policy in 2021 and a phased implementation

period from 2022–2026.

Analysis of these scenarios shows that national

universal workplace access scenarios could

reduce the access gap and expand retirement

savings coverage by 28 to 40 million workers

(depending on the chosen design features) by

the year 2040, with additional participation from

50 to 70% of private sector workers currently

lacking access. Because employees can choose to

opt out, no scenario will achieve 100% participation

by all eligible workers. Nevertheless, by starting

to save early in their careers, through simple,

automatic, and consistent contributions, and by

capitalizing on incentives to save and compounding

investment returns over an extended time horizon,

millions of additional private sector workers with

typical earnings levels will begin to save and build

substantial private savings that will increase their

retirement incomes.

Starting Sooner and Saving Longer Signicantly

Improves Retirement Outcomes

Because the scenarios analyzed examine the

impact on coverage and savings through the

year 2040, retirees within this time frame only

include the cohort of older savers who will begin

to access retirement savings. However, younger

workers from the millennial and Gen Z cohorts

who will not yet have reached retirement age

within the study period have greater opportunities

to build assets through continued contributions

and additional years of compounding growth.

As a result, future generations of Americans will

see far greater benets from savings than those

quantied as of 2040 within these estimates.

A simple illustration of the additional supplemental

lifetime income at age 65 for a young Roth Auto-IRA

Figure ES.5: Modeled Scenarios Isolate the Impact of Policy Variations on Access and Savings

√

√

√

√

√

√

√

√

√

√

√

√

√

√

5

© 2020 Georgetown University Center for Retirment Initiatives What are the Potential Benets of Universal Access to Retirement Savings?

saver demonstrates the long-term benets to the

youngest workers, who will not have yet reached

retirement age by 2040. A young (25-year-old) saver

with modest earnings levels of around $35,000

per year contributing at the default level (5% auto-

escalating up to a cap of 10%) envisioned in the

baseline scenario would make contributions of

about $110,000 over a 40-year period, and have

an account that grows to more than $262,000 in

assets. If this lump sum is used to purchase an

immediate xed annuity at the age of 65, it would

generate an annual supplemental income stream of

$14,320 over the remainder of the saver’s lifetime

(see Figure ES.6). The returns for this young saver

could be helped even more by making an enhanced,

refundable Saver’s Tax Credit (“Saver’s Credit”)

available that would boost savings to more than

$390,000 and generate an annual supplemental

income stream of $21,300 for the remainder of the

saver’s lifetime.

The benets of starting sooner and saving longer

can produce signicant improvements in retirement

income outcomes and long-term retirement security.

The passage of time and the power of compound

interest boost savings, because future market returns

apply not only to initial contributions, but also to the

market returns already achieved. This compounding

dynamic means that options that encourage savings

at a younger age can have signicant long-term

payos for participants, even in instances where

savers are not able to contribute to their accounts

throughout their entire careers, as balances built

up in early years continue to grow throughout the

duration of a saver’s working years.

Expanding Access to Retirement Savings

The ability to close the access gap and boost

savings will be aected by the design of the savings

option. The type of retirement savings accounts

(IRA and/or 401(k) structure), the employers required

to participate, and the default levels of employee

contributions and any employer contributions over

time are all factors that will drive access, savings,

asset growth, and retirement income.

The Auto-IRA model with no employer threshold

(“Baseline Auto-IRA”) would expand access to

workers at all private sector rms, increasing

participation by more than 40 million workers in

the year 2040 (with the remaining workers gaining

access but choosing to opt-out of saving).

Participation levels fall signicantly if employers

below a certain employee threshold are exempt.

Policy options, whether through an Auto-IRA or

401(k) approach, that exempt smaller and younger

rms from the requirement to provide access would

limit the degree to which the scenarios can close

the access gap. As an example, an exemption of

Figure ES.6: Supplemental Lifetime Income at age 65 for a Young Auto-IRA Saver

(With and Without a Refundable Saver’s Credit)

65

55

453525

Assets w/ Credit: $390,456

Annual Annuity: $21,300

Assets w/o Credit: $262,427

Annual Annuity: $14,320

Contributions: $110,122

$0

$100,000

$200,000

$300,000

$400,000

6

© 2020 Georgetown University Center for Retirment InitiativesWhat are the Potential Benets of Universal Access to Retirement Savings?

rms with fewer than 10 employees or in existence

less than two years would reduce participation by

an estimated 11 million workers by 2040 under an

Auto-IRA model (“Threshold Auto-IRA”), with modest

additional reductions in coverage under 401(k)

approaches because of anticipated variations in the

number of rms and workers likely to participate (see

Figure ES.7).

Encouraging Savings and Asset Growth

While participation levels are lower in models

exempting some employers, those participating

may have higher average contributions and

savings. These dierentials are due in part to the

characteristics of the covered population (with

average participant earnings increasing when

excluding rms below an employer size and age

threshold). Dierences also arise between types of

savings accounts, with a 401(k) model producing

higher average contributions and savings levels

relative to an IRA model for any given employer

threshold level.

Average savings levels increase with a 401(k) model

with discretionary employer contributions (“Voluntary

Employer Contribution 401(k)”) when compared to

the IRA models due to matching or supplemental

contributions from some employers, the eect of

the increased annual contribution limit on a small

sub-set of savers, and lower anticipated levels of

early withdrawals. Savings levels are estimated to

be slightly lower under a 401(k) approach requiring

employer contributions (“Mandatory Employer

Contribution 401(k)” relative to a voluntary employer

contribution 401(k) approach, due in part to the

constraint on wage growth for workers from the

required employer contribution.

Average account balances for participants reaching

age 65 in 2040 grow from $66,300 in the threshold

Auto-IRA scenario to $75,200 under the voluntary

employer contribution 401(k) approach. The tradeo

for the higher balances for some savers is that a

larger number of workers will remain uncovered. The

baseline Auto-IRA model generates a lower average

account balance for participants reaching 65 of

$60,600 due to participation of more low-income

workers, which decreases average balances.

However, the baseline Auto-IRA that covers

all employers has the highest overall level of

savings. While per-participant savings are higher

under alternative approaches, the expansion of

coverage anticipated under the baseline Auto-IRA

scenario with no employer threshold leads to the

largest increase in overall savings among the policy

options modeled.

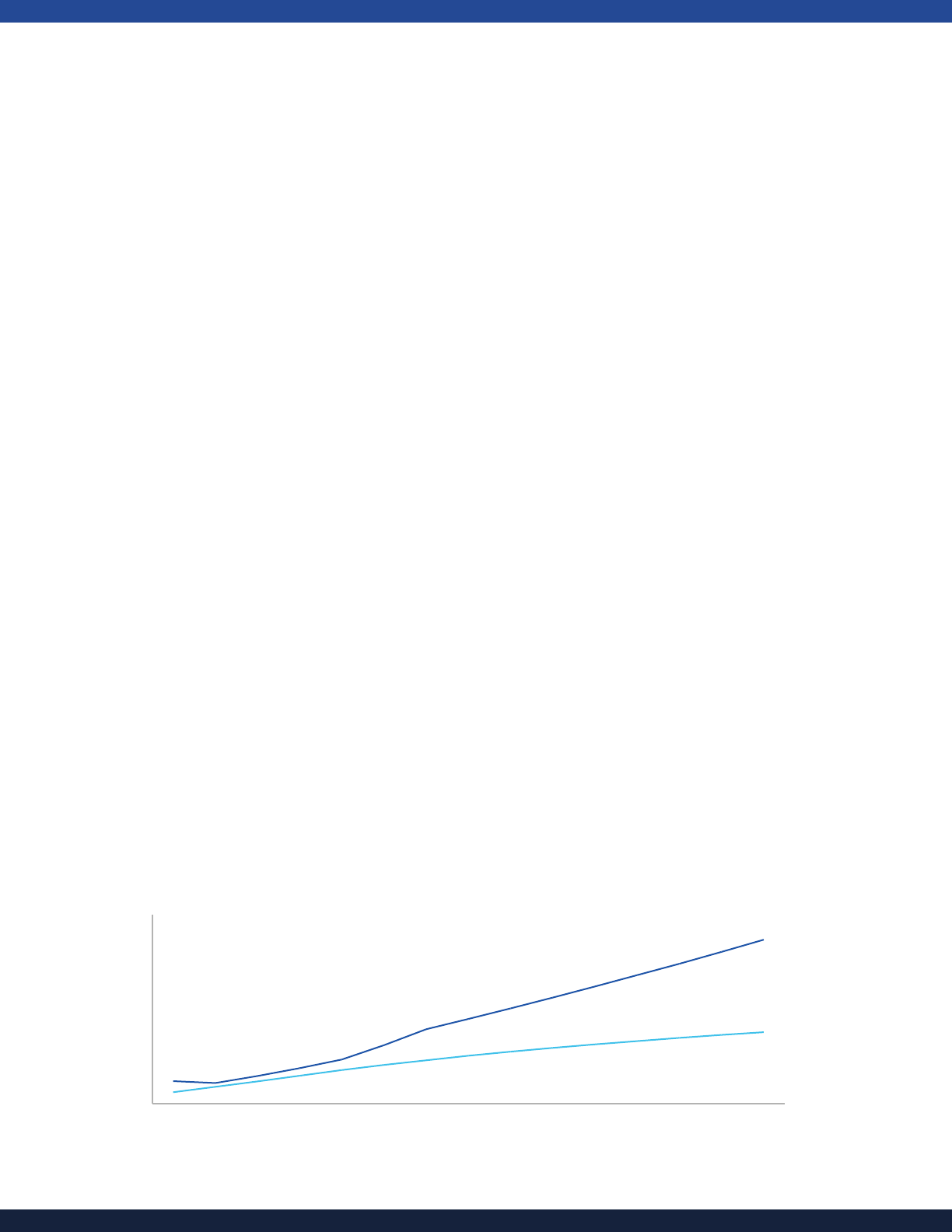

Annual contributions to savings accounts are

estimated to total more than $130 billion by 2040

under the baseline Auto-IRA model, adding up to a

cumulative $1.89 trillion over the analysis period,*

with policy alternatives producing $1.4–$1.5 trillion

in cumulative contributions (see Figure ES.8). Among

options with an employer threshold, the voluntary

employer contribution 401(k) generates slightly

higher savings levels than threshold Auto-IRA model.

These results illustrate potential trade-os for

consideration between payroll deduction IRA and

401(k) options. When analyzed using equivalent

employer thresholds, an IRA model encourages

a higher level of participation by presenting the

lowest barriers to participation for businesses and

savers. However, a 401(k) approach can encourage

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

40.4

29.6

28.3

28.1

Access Gap Among Workers <65 (2040): 58.6M

Figure ES.7: Required Universal Access to

Savings Options Can Increase Participation

by 50 to 70% Among Workers Currently

Lacking Access

Active Program Participants, 2040 (M)

Baseline

Auto-IRA

Mandatory

Employer

Contribution

401(k)

Voluntary

Employer

Contribution

401(k)

Threshold

Auto-IRA

7

© 2020 Georgetown University Center for Retirment Initiatives What are the Potential Benets of Universal Access to Retirement Savings?

higher average levels of contributions and asset

accumulation over time among those who do

participate due to its provisions around contributions

and withdrawals.

If feasible, a voluntary employer contribution

401(k) approach without a threshold for required

participation (similar to the baseline Auto-IRA

scenario) or a mandatory employer contribution

401(k) approach with a more-aggressive employer

contribution level could produce higher levels of

savings than the baseline Auto-IRA model. However,

these approaches and requirements have impacts

on participating businesses and the broader

savings market, and federal 401(k) or IRA legislative

proposals to date have typically contemplated

an employer threshold out of consideration for

the implications for the smallest businesses. The

inclusion of the baseline Auto-IRA scenario is

intended to show how important the decision of

whether to include and where to draw an employer

participation threshold is to overall levels of access,

participation, and savings.

Part 3: Long-Term National Impacts from

Increased Savings

In addition to the impacts on participating savers,

enhancing access, and building retirement savings

would have “downstream” impacts on the broader

economy and the nation’s scal health.

Increased Economic Growth and Tax Revenue

Savings programs have implications for the

everyday decision-making of businesses, workers,

and families. These individual microeconomic

decisions around what job to take, whether to start

a business, and how to spend disposable income

aggregate together to have signicant impacts on

the economy. More-accessible savings options help

the competitiveness of small businesses and the

nancial security of workers, including the self-

employed, encouraging a more-dynamic economy,

while increased savings levels grow the income

that senior households have available to spend in

retirement. In addition to the returns they generate

for individuals, personal savings provide a source of

capital for business investment and growth.

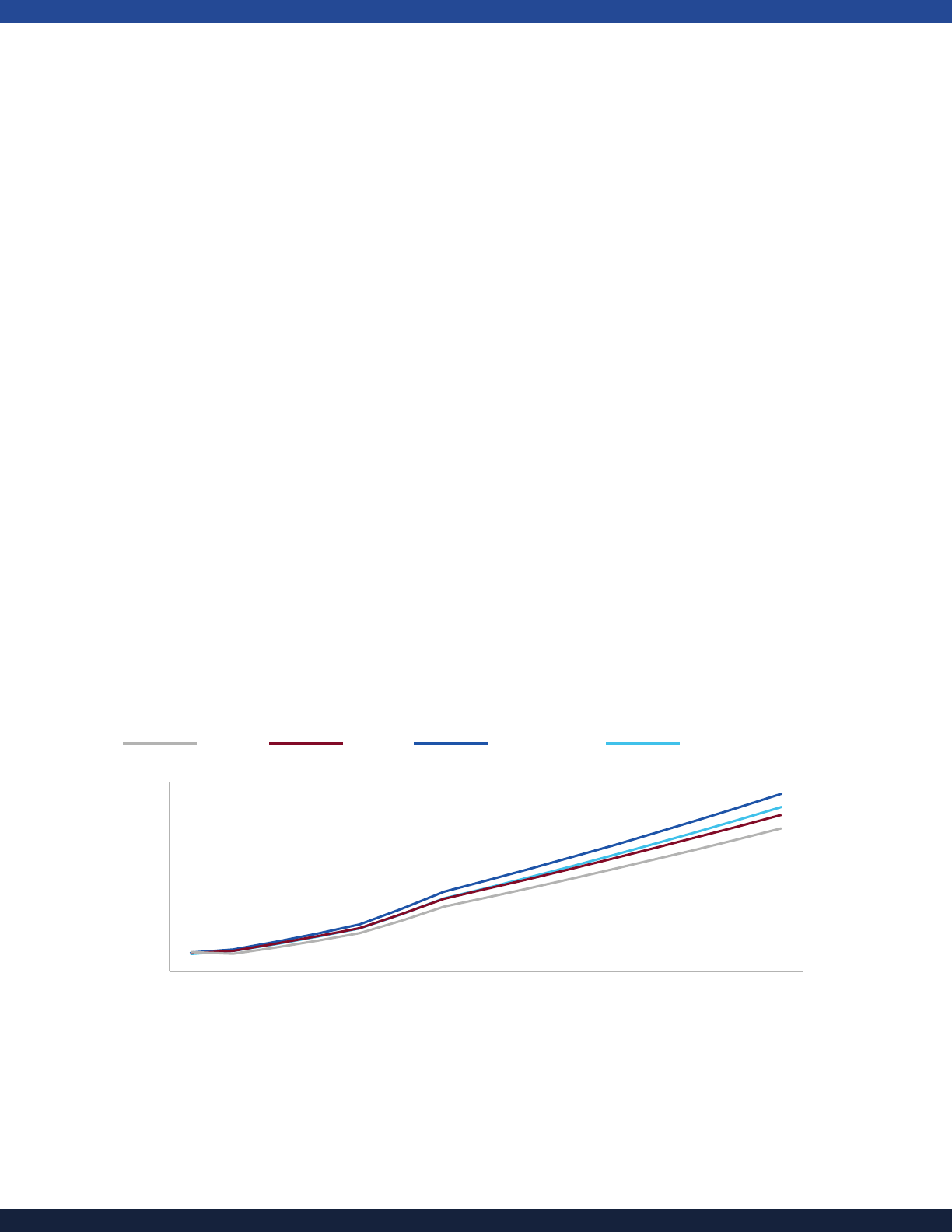

Increased productivity growth from increased

savings and investment accelerates GDP growth.

Expected increases in the growth rate from the

scenarios analyzed would add $72–$96 billion

(depending on program design) to the national GDP

in the year 2040 (see Figure ES.9).

Increases are highest under the baseline Auto-IRA

approach, which generates the largest increase in the

personal savings rates through the highest coverage

levels, thus stimulating the greatest productivity

growth. Among scenarios with an employer

threshold, the voluntary employer contribution 401(k)

generates slightly more growth than the threshold

Auto-IRA, though in either case the tradeo is that

the overall coverage is signicantly lower than the

baseline scenario. Increased economic activity

would also grow the tax base, increasing federal tax

collections in the year 2040 by $11–$14 billion.

*A phased implementation period is assumed from 2022–2026 for a policy

enacted in 2021, with participation in early years consistent with

some voluntary early sign-ups by employers before a phased

implementation of coverage requirements by employer size.

$132

$1.89 T

$1.53 T

$1.48 T

$1.42 T

Cumulative

$0

$30

$60

$90

$120

$150

2040

2035

2030

2025

2022

Total Contributions ($Billions)

Figure ES.8: Cumulative Savings Contributions

are Highest Within the Baseline Auto-IRA Model,

Totaling $1.9 Trillion through 2040

Baseline

Auto-IRA

Threshold

Auto-IRA

Voluntary Employer

Contribution 401(k

)

Mandatory Employer

Contribution 401(k)

8

© 2020 Georgetown University Center for Retirment InitiativesWhat are the Potential Benets of Universal Access to Retirement Savings?

Reduced Benet Program Spending

Reduced demand for government benet programs

is another long-term impact of increasing retirement

security. Several federal programs provide a

range of support resources to elderly Americans

with demonstrated needs, including health care,

nutrition, housing, and supplemental income. Federal

spending on these programs already totals nearly

$100 billion per year and is often supplemented

by state funding. Federal expenditures on these

programs are anticipated to grow by $75 billion

over the next two decades (absent any change in

retirement income trends) as the composition of

the population changes, increasing the demand

from an elderly population and the tax burden on

proportionately smaller generations of future workers.

The modeled universal access scenarios are all

expected to diminish this rate of growth in program

expenditures for low-income seniors over time by

increasing savings and retiree resources. Federal

and state governments share in these savings,

due to the shared nature of many programs. Federal

savings in the year 2040 under the baseline Auto-

IRA scenario are estimated at $6.2 billion and state

savings at $2.5 billion, for a total of $8.7 billion,

while alternative scenarios generate an estimated

combined federal and state program savings of

approximately $7 billion in 2040.

Conclusion

Any eort to signicantly improve retirement

readiness must expand access to ways to save for

retirement to as many workers as possible. The

ability to close the access gap and boost savings

will be aected by the way a program is designed.

The type of retirement savings accounts (IRA and/

or 401(k) structure), the employers required to

participate, and the default levels of employee

contributions and any employer contributions over

time are all factors that will drive access, savings,

asset growth, and retirement income.

Regardless of the model selected, what is clear is

that the benets to savers, retirees, and the nation’s

scal and economic well-being can be enormous.

Depending on the design features, a national

approach to universal access to retirement savings

which would require some or all employers to oer

their workers either an IRA or 401(k) could:

• Increase the number of workers saving for

retirement in the year 2040 by 28–40 million,

with participation from about 50–70% of private

sector workers who currently lack access;

• Help a young worker with a modest income who

starts saving early and follows program defaults

for 40 years to save enough to generate as

much as $14,320 in additional annual income

for retirement, increasing to $21,300 in annual

income if eligible to take advantage of a

refundable Saver’s Credit;

• Increase cumulative total retirement savings by

$1.4–$1.9 trillion by the year 2040; and

• Accelerate economic growth, increasing

national GDP by $72–$96 billion in the year

2040.

Experiences from other countries and the early

evidence from states here in the US demonstrate

that increases in access can be achieved in a simple,

cost-eective way that supports and includes a

private market of providers ready and willing to

compete to provide such options for employers and

their workers.

Additional Annual US GDP ($Billions)

$96 B

$78 B

$76 B

$72 B

$0

$20

$40

$60

$80

$100

$120

Figure ES.9: Increased Savings and Investment

Boost GDP Growth by $72–$96 Billion in

the Year 2040

Baseline

Auto-IRA

Threshold

Auto-IRA

Voluntary Employer

Contribution 401(k

)

Mandatory Employer

Contribution 401(k)

2040

2035

2030

2025

2022

9

What are the Potential Benets of Universal Access to Retirement Savings?© 2020 Georgetown University Center for Retirment Initiatives

1.1 Signicant Gaps Remain in Access to

Retirement Savings

Workers in the United States are being asked to take

responsibility for their nancial well-being in retirement

now more than ever. What used to be considered the

foundation for building a secure retirement — Social

Security, employer-provided pensions, and personal

savings — has been weakening for decades as

traditional dened benet (DB) pension plans have

been replaced by a dened contribution (DC) system

of savings that was originally meant to supplement,

not replace, traditional pensions.

Most employers today that have retirement plans only

oer DC options. This shift over time from employer-

provided pensions to DC plans has put greater

responsibility on workers to make complex savings

and investment decisions that will aect the amount

of money available in retirement. Even Americans

who have access to retirement savings accounts

often do not save enough to maintain their quality of

life in retirement. Making this situation worse is the

reality that almost half of all private sector workers do

not have access to employer-sponsored retirement

savings plans to help them save.

A rapidly aging population and dierences across

generations increase the urgency to address

retirement savings shortfalls. As senior households

grow in both in number and as a share of the

population, there will be fewer working households

to support the needs of the elderly, non-working

population. This demographic shift makes the

ability of elderly households to maintain their living

standards in retirement an important economic and

quality of life issue for all US households.

Over the next decade, for example, the nal wave of

baby boomers will reach retirement age, Generation

X will approach retirement, and millennials and

increasingly Generation Z will be in their prime

working years. This shift in population composition

also underscores the importance of enabling younger

generations like millennials and Gen Z (which by 2040

will cover the prime working ages of 30–60) to have

opportunities during their crucial savings years to

build resources to support their nancial futures.

Gaps in Private Sector Access Disproportionately

Impact Certain Groups

Millions of private sector workers in the United States

lack access to an employer-sponsored retirement

savings plan. Estimates of the size of this “access

gap” range signicantly based on the data source

and method of analysis, ranging from 33% (about

40 million) to 64% (about 80 million) of the roughly

125 million private sector employees in the United

States.

3

Using a blend of data from the Current

Population Survey of the US Census Bureau and

the National Compensation Survey from the Bureau

of Labor Statistics, this analysis estimates that

46% of private sector workers lack access to an

employer-sponsored plan, representing about 57

million workers as of 2020 (see Figure 1.1).

4

This

gure is anticipated to grow to more than 64 million

by 2040 under the continuation of current trends.

Workers are much more likely to save for retirement

if they have access to an employer-sponsored

retirement savings plan. Although workers can

establish their own retirement savings accounts

if they lack such access, they rarely do so in

1. Closing the Signicant Gaps in Access to Retirement Savings

ESI analysis of Census Bureau Current Population Survey

and BLS National Compensation Survey Data.

Access to coverage at work

Coverage access gap

67.3M57.3M

46%

GAP

124.6 M

Private Sector Employees

Figure 1.1: More than 57 Million Employees Lack

Access to a Retirement Savings Plan in their

Workplace (2020)

10

© 2020 Georgetown University Center for Retirment InitiativesWhat are the Potential Benets of Universal Access to Retirement Savings?

practice, with workers 15 times more likely to

save for retirement if they have access to a payroll

deduction savings plan at work.

5

Workers at

rms that provide an employer-sponsored plan

are considered to have access to coverage,

although they may not choose to be participants.

For small businesses, the complexity, cost,

and perceived legal risk reduce the likelihood

they will oer a plan to their employees.

Programs that make access to savings easier

by connecting a worker to a savings account

and including design features such as automatic

enrollment and auto-escalation can signicantly

increase participation and savings levels.

6

The gaps in access to retirement savings plans

are greater among younger workers, women,

minorities, and lower income workers.

7

Access to

retirement savings plans also varies signicantly by

employer size and industry. Larger employers — for

example, those with more than 500 employees, and

in sectors paying higher wages — are more likely

to oer their workers retirement savings plans.

8

These dierences contribute to variations in access

among demographic groups and widen access

gaps among dierent segments of the population.

Too Many Have Little Saved for Retirement

These gaps in access have serious implications,

leaving many ill-prepared nancially for retirement.

While elderly Americans are supported by

Social Security, many elderly households fall

short of the income replacement standards

recommended to maintain the quality of life they

enjoyed during their working years. Even when

considering a generous measure of retirement

savings (net worth), more than three-quarters of

Americans fall short of conservative retirement

savings targets for their age and income level.

9

Putting Social Security in Context

Social Security is one of the key pillars of the

American retirement system, but was never

designed to meet all retirement income needs.

Social Security provides a basic retirement income

oor for retirees and should be supplemented

by employer-based and personal savings. In

2020, the average monthly Social Security retiree

benet was $1,503 per month for an individual,

equivalent to an annual income of just 1.4x the

Federal Poverty Level, or $2,531 for a couple.

10

Unfortunately, a signicant proportion of the retired

population in the US has come to rely on Social

Security for a material proportion, if not all, of their

retirement income. Among elderly Social Security

beneciaries, 70% of unmarried people receive half

or more of their income from Social Security, as do

50% of married couples. About 45% of unmarried

people rely on Social Security for 90% or more of

their income.

11

While a large share (42%) of the

baby boomer cohort expects to rely heavily on

Social Security as a source of income in retirement,

younger generations are expecting lower income

replacement from Social Security and to rely primarily

on self-funded savings for retirement income.

12

Shortfalls in Private Savings

The shift over time from employer-provided

pensions to dened contribution plans has put

greater responsibility on workers to ensure their

nancial well-being in retirement. However, even

Americans who have access to retirement savings

accounts often do not achieve sucient savings

levels to maintain their quality of life in retirement.

Researchers from the Center for Retirement

Research at Boston College report that median

account balances for 55- to 64-year-old working

households with incomes near the median are below

$100,000.

13

For lower income households who are

less likely to have access to retirement savings plans

through their employers, the retirement readiness

gap is even more stark. Among workers nearing

retirement with the lowest 20% of income, 79%

have no retirement account assets whatsoever.

14

Younger generations are also struggling to build

the foundational savings that will help support their

retirement readiness. Young savers face a range of

challenges, such as rising educational costs and

student loan debt burdens, challenges in securing

housing, and a cycle of economic challenges. Amidst

these challenges, two-thirds of working millennials

lack any retirement savings, raising concerns

about their long-term retirement readiness.

15

11

© 2020 Georgetown University Center for Retirment Initiatives What are the Potential Benets of Universal Access to Retirement Savings?

An Aging Population Increases the Urgency

Within this context, a rapidly aging population

and dierences between generations increase the

urgency to address retirement savings shortfalls.

Over the next decade, for example, the nal

wave of baby boomers will reach retirement

age, Generation X will approach retirement,

and millennials and increasingly Generation

Z will be in their prime working years.

The aging of the baby boomers continues a shift

that has been occurring for decades in the balance

between the retiree and working-age population.

The University of Virginia’s Weldon Cooper Center

projects the nation’s elderly population will increase

from 54 million in 2020 to 71 million by 2040, a

growth rate of 32%, about three times the rate of

the non-elderly population.

16

This also aects the

composition of US households, with households

headed by seniors anticipated to grow from 33

million in 2020 to 43 million in 2040, an increase of

more than three times the expected rate of growth

for working age households (see Figure 1.2).

17

As senior households grow in both in number

and as a share of the population, there will be

fewer working households to support the needs

of an elderly, non-working population. Census

Bureau data indicate that the “dependency ratio”

is currently falling rapidly from its historic norms

— from almost four working age households

for each elderly household in 2005 to a ratio of

closer to two to one by 2030 (see Figure 1.3).

Since working age households are the primary

contributors to the tax base, this falling dependency

ratio will create signicant scal pressures as

demand for benet programs increases. This

demographic shift makes the ability of elderly

households to maintain their living standards in

retirement an important economic and quality of

life issue for all US households. While considerable

focus has been placed on the future scal

solvency of Social Security and Medicare, several

means-tested programs like Medicaid and the

Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP)

also will see signicant increases in demand

if elderly households lack sucient income in

retirement. This also portends a lower economic

growth environment, with the workforce growing

at a slower rate than in prior generations.

Structural factors indicate that this shift in the

balance between retiree and younger households

is likely to reect a new normal. Increasing life

expectancy will help to grow the elderly population,

while younger generations show declining birth rates

and are having their rst children later in life (slowing

generational replacement cycles). Figure 1.4 shows

projected changes to the US “population pyramid”

by age and generation over the next two decades.

This shift in population composition underscores

the importance of enabling younger generations

Figure 1.3: ... While Falling Ratios of Working-Age

to Elderly Households Create Fiscal Pressure

ESI analysis of US Census Bureau data

and University of Virginia Population Projections.

3.9

3.8

3.6

3.6

3.8

3.9

3.7

3.2

2.8

2.5

2.3

2.3

2.3

2040203520302025202020152010200520001995199019851980

US Households (Millions)

2020

2040

7.2

44.9

48.4

43.4

6.3

40.0

45.9

32.8

65+45-6425-44<25

Age Group

+13%

+12%

+5%

+32%

Figure 1.2: Senior Households are

Growing as the Population Ages ...

ESI analysis of American Community Survey Data

and University of Virginia Population Projections.

12

© 2020 Georgetown University Center for Retirment InitiativesWhat are the Potential Benets of Universal Access to Retirement Savings?

like millennials and Gen Z to have opportunities to

build resources during their crucial savings years. By

2040, the millennial and Gen Z cohorts will occupy

the prime earnings years of ages 30 to 60 and will be

helping to supporting a larger retiree population than

ever before while trying to ensure their own nancial

futures. Enhancing the ability of these generations

to strengthen their nancial security is crucial to the

nation’s long-term economic health and prosperity.

1.2 Policy Approaches Taken to Close the

Access Gap

Policymakers in the United States have developed

and started to implement reforms intended to

close the gap in private sector retirement savings

access, encourage savings, and strengthen the

retirement readiness of workers. Such eorts are

not unique to the US, with other countries having

already adopted a mix of public and private

models to move toward universal access that

have resulted in signicant savings over time.

National universal access models have been

proposed by academics and policy experts, and

several legislative proposals have been introduced

in Congress over the past decade and as recently as

2019. In the absence of national action, several states

have adopted innovative public-private partnership

models to expand access requiring employers to

provide a retirement savings option for their workers.

A few of these new state programs have launched,

providing many employers and their employees with

new ways to save, and the number of new accounts

and assets are now growing at a steady pace.

18

At

the same time, recent Congressional action, such as

the SECURE Act (P.L. 116-94), intended to expand

the adoption and improve the design of dened

Millennials

and Gen Z

30 - 60

Years

Figure 1.4: Millennials and Gen Z will be in Prime Earnings and Savings Years by 2040

Post-Alpha Alpha Gen Z Millennials Gen X Boomers Silent

ESI analysis of American Community Survey Data and University of Virginia Population Projections

US Population (M)

Age Cohort

85+

80 to 84

75 to 79

70 to 74

65 to 69

60 to 64

55 to 59

50 to 54

45 to 49

40 to 44

35 to 39

30 to 34

25 to 29

20 to 24

15 to 19

10 to 14

5 to 9

0 to 4

2020 2040

13

© 2020 Georgetown University Center for Retirment Initiatives What are the Potential Benets of Universal Access to Retirement Savings?

contribution plans is another positive step.

19

However,

both of these initiatives are unlikely to achieve a

signicant national expansion of coverage and

savings.

International and state examples, as well as national

proposals advanced by legislators and policy experts,

provide several scenarios intended to achieve the

goal of universal access. This section reviews these

approaches and outlines a set of policy scenarios that

are modeled and analyzed in Part 2 of this study to

see how they expand access and boost retirement

income.

International Models Toward Universal Access

Several countries have launched programs to

provide universal workplace access to retirement

savings options. These programs feature a mix of

public and private structures for administration and

contributions. Common elements include automatic

features to help make enrollment and saving easier

for participants, which helps to build scale and

control costs.

Programs in Australia, New Zealand, and the United

Kingdom, for example, have gained signicant

scale over time, with millions of participants

and billions in assets under management (see

Figure 1.5). Their stories demonstrate the

sustainability of these types of programs and

their potential to build signicant wealth.

Australia: Superannuation Guarantee

Launched in 1992, the Superannuation Guarantee

in Australia requires employers to contribute

to a retirement savings account on behalf of

eligible employees. Employers are currently

required to contribute 9.5% of an employee’s

earnings to a superannuation (or “super”) fund

on behalf of workers above certain salary and

hours thresholds.

20

The guaranteed contribution

rate will rise to 12% by July 2025. Contributions

are not required for very-low-wage and part-

time workers. However, contributions made for

low- and middle-income workers are matched

by the national government up to a maximum

amount of $500 annually to help build assets.

21

Although most employees are free to determine

which fund they prefer their employers contribute to,

many allow default investment funds to be applied.

Funds can be organized by a nancial services

company, employer or industry group, or through

self-managed funds for ve people or fewer.

As of 2020, 16.7 million Australians held super-

accounts and super-fund assets totaled $2.9 trillion.

The average account balance of those with savings

in super-funds (non-zero balances) is approximately

$121,000 for women and $169,000 for men.

22

New Zealand: KiwiSaver

Launched in 2007, the KiwiSaver is a publicly

administered dened contribution system in New

Zealand. Participation is voluntary, but its auto-

enrollment feature requires that a worker must

opt out if they choose not to participate. Once an

account is created, it is portable among employers

and requires contributions from both employers

and employees. Employees set a contribution level

of 3% or higher of earnings, employers provide a

contribution of 3% of earnings, and the government

makes an additional “tax credit” contribution.

Early withdrawals are highly restricted before

the retirement age of 65, but employees may

be able to make early withdrawals of part (or

all) of their savings if they are buying a rst

home, moving overseas permanently, suering

signicant nancial hardship, or seriously ill. As

Figure 1.5: Employer-Based International

Savings Programs

Australia Superannuation Guarantee – 16.7 million

participants

Requires employers to contribute 9.5% of an eligible

employee’s earnings to a retirement savings account.

KiwiSaver – 3 million participants

Workers auto enrolled (can opt out) to contribute ≥

3% of earnings + 3% employer match and a tax credit

contribution.

UK NEST – 9 million participants

Uncovered workers auto enrolled (can opt out) at default

contribution levels of 5% employee + 3% employer.

14

© 2020 Georgetown University Center for Retirment InitiativesWhat are the Potential Benets of Universal Access to Retirement Savings?

14

of 2020, KiwiSaver has grown to more than 3

million participants and $62 billion in assets.

23

United Kingdom: National Employment Savings Trust

(NEST)

NEST is a dened contribution savings plan in the

United Kingdom that launched in 2012. It provides

individualized savings accounts to those who do

not have access to an employer-based plan. The

NEST program’s administration is funded through

fees on contributions, and program services

are contracted to private nancial providers by

the NEST board. Employers can participate in

private sector plans or use the NEST program,

which essentially functions as a public option.

NEST is required to take any employer, but the

self-employed are currently not covered.

Workers must be auto enrolled, and they can choose

from a set of investment options, including target

date funds, but there must be a default investment

option and fees are capped at 75 basis points.

Default contribution levels for the plan have grown

over time to 5% of earnings for the employee and

3% of earnings for the employer, totaling 8%. The

overall savings opt-out rate is about 10% and 99% of

participants stay with the default investment option.

As of March 2020, the program had grown to more

than 9 million participants, received $4.8 billion in

contributions, and had $9.5 billion in assets.

24

US Eorts Have Fallen Short of Universal Access

State Eorts to Enhance Savings

Due to the continued failure of Congress to take

action to close the access gap, several US states

are adopting simple, low-cost, easily accessible

ways for more private sector workers to save for

retirement. States are acting out of necessity.

They already understand that they face signicant

budgetary and economic consequences if their

residents retire with insucient retirement income.

As the population ages, states will be increasingly

pressed to deal with dramatic increases in the cost

of social service programs for seniors living at or

below the poverty line — namely, programs related

to healthcare, housing, food, and energy assistance.

ESI studies for task forces examining the issue

of insucient retirement savings in Pennsylvania

and Colorado have shown that the “cost of doing

nothing” for each of these states will amount

to several billion dollars in additional state

expenditures.

25

For a representative household

in Colorado, the study found that additional

savings of just over $100 a month over 30 years

could close the gap and achieve recommended

income replacement levels in retirement.

26

Recognizing the signicant costs of doing nothing,

states across the country have initiated a variety

of eorts aimed at helping private sector rms

overcome the barriers to oering retirement savings

options for their employees. Since 2012, at least 45

states have introduced legislation to either establish

a state-facilitated retirement program for private

sector workers or study the feasibility of establishing

one.

27

States are designing dierent models that

seek to address these issues (see Figure 1.6).

State-facilitated programs seek to establish the

program architecture and administration at a

statewide level, enabling employers to participate

with minimal eort. The state generally appoints a

board to develop program rules and contract with

administrative and investment managers. Program

funding is covered by fees to the participants, and

states do not subsidize the program ongoing or

assume nancial liability for investment outcomes.

There are currently three basic state models with

variations considered:

Auto-IRA: The most common approach for state-

facilitated programs has been a payroll deduction

“Auto-IRA” model. States facilitate a simple and

low-cost IRA program using automatic enrollment,

a voluntary enrollment mechanism where the saver

has complete control over participation in the

program and can opt out at any time or change

the default contribution level. All the employer

must do is provide basic employee information

to the program, and remit payroll deductions.

Employers who do not already have a plan of their

own would be required to facilitate the use of the

state program for their workers. These programs

seek to maximize participation and savings and

15

© 2020 Georgetown University Center for Retirment Initiatives What are the Potential Benets of Universal Access to Retirement Savings?

minimize fees through automatic features, simple

design in investment options, and scale. Active

programs in California (CalSavers), Illinois (Illinois

Secure Choice), and Oregon (OregonSaves)

follow this approach (see Figure 1.7).

Participation in the Auto-IRA programs is typically

required for private rms meeting certain criteria

(such as a size threshold) if they do not already

oer their employees a qualifying alternative.

However, a program also can be structured as a

voluntary payroll deduction option that is voluntary

for both employers and employees, requiring opt-

in. This approach has been adopted, but not yet

implemented, by New York and New Mexico.

Multiple Employer Plans (MEPs): A MEP is

essentially a 401(k) used by several businesses

that join together to oer a common plan to each

employer’s workforce, pooling their resources and

outsourcing plan management. Because 401(k) plans

are ERISA plans, participation by employers must

be voluntary.

28

This scenario is currently operating

in Massachusetts and will soon launch in Vermont.

Marketplace: A marketplace by design is

a voluntary platform that creates a single

“clearinghouse” for private sector providers to

oer plans. It enables small businesses to nd and

compare retirement savings plans in an apples-

to-apples manner. It presents a diverse array of

plans (IRAs and 401(k)s) pre-screened by the state

to ensure certain standards are met. This reduces

search costs for employers, allowing them to rely

on the state to establish certain standards for plans

oered and ensure that the oerings meet those

standards. This model is currently operating in

Washington.

Hybrid: In addition to these three basic models,

states also have considered combining these models

to create a “hybrid” version of a program. New

Mexico is the rst state to adopt a hybrid model

that includes both a voluntary payroll deduction IRA

and a marketplace. Other options considered but

not yet adopted include oering both an Auto-IRA

and a MEP or combining all three approaches.

To date, international experience with the KiwiSavers

program in New Zealand and early state experiences

with MEPs and marketplaces in the US suggest that

it is much more challenging for a voluntary program

to achieve signicant reductions in the access gap.

29

Figure 1.7: Recently Launched State Auto-IRA

Programs

OregonSaves – Launched 2017

Auto-IRA program required for all employers without an

existing qualied plan, 5% default employee contribution

with auto-escalation, and no employer match permitted.

Illinois Secure Choice – Launched 2018

Auto-IRA program required for employers with ≥ 25

employees without an existing qualied plan, 5% default

employee contribution, and no employer match permitted.

CalSavers – Launched 2019

Auto-IRA program required for employers with ≥ 5

employees without an existing qualied plan, 5% default

employee contribution with auto-escalation, and no

employer match permitted.

Figure 1.6: State-Facilitated Retirement Savings Models Adopted to Date

Auto-IRA

(Secure Choice)

Voluntary IRA

Voluntary

Marketplace

Voluntary Open Multiple

Employer Plan (MEP)

California (active)

Illinois (active)

Oregon (active)

Colorado

Connecticut

Maryland

New Jersey

New York Washington (active) Massachusetts (active)

Vermont

New Mexico (hybrid)

16

© 2020 Georgetown University Center for Retirment InitiativesWhat are the Potential Benets of Universal Access to Retirement Savings?

SECURE Act

In December 2019, Congress passed the Setting

Every Community Up for Retirement Enhancement

(SECURE) Act (P.L. 116-94) to allow small business-

es to provide retirement savings options for their

employees using Multiple-Employer Plan (MEP)

and Pooled Employer Plan (PEP) arrangements.

30

A MEP structure allows and makes it easier for

related businesses to join together in a single

retirement plan. MEPs are organized and run by

a sponsoring entity (which may or may not be

a dened membership organization, such as an

industry association) that is responsible for admin-

istrative duties and takes on duciary liability for the

plan. The SECURE Act made this structure easier to

establish and more appealing, by reducing auditing

requirements and eliminating the “one bad apple”

rule, where compliance failures of one employer

could disqualify an entire plan. A PEP structure,

introduced under the SECURE Act, allows unrelated

employers to band together to form a single retire-

ment plan through a 401(k) savings vehicle. This

structure envisions common administration through

a third-party administrator or bundled record-keeper.

These new provisions, eective as of 2021, give

small employers additional options that may reduce

costs to plan participants through increased scale.

A recent analysis by Morningstar found that “MEP

fees decrease and become more predictable as

plans grow,” with decreases in fees per participant as

assets grow outweighing smaller increases in admin-

istrative cost per participant as the number of par-

ticipants grows.

31

This suggests that expanded MEP

and PEP availability could provide better options for

rms that currently operate on single employer plans.

However, fees for MEP plans that fail to achieve

signicant scale often remain high and may lack

transparency due to limited reporting requirements

for smaller plans. While these provisions are con-

structive steps, MEPs and PEPs are unlikely to mate-

rially reduce the access gap if they remain voluntary.

The SECURE Act also includes provisions to help

savers plan for and manage their savings once they

retire, in the form of a monthly income throughout

their lifetimes. The Act requires, for the rst time,

that statements to plan participants include in-

formation about the monthly income their current

savings would generate in retirement. The SECURE

Act also makes it easier from a regulatory stand-

point for plan providers to oer lifetime income

solutions (annuities). These provisions reect an

increasing emphasis on improving dened contri-

bution plans as lifetime income-generating plans

to support a better quality of life in retirement.

In October 2020, House Ways and Means Committee

Chairman, Representative Richard Neal and Ranking

Member, Representative Kevin Brady introduced

the Securing a Strong Retirement Act of 2020 – a

“SECURE ACT 2.0.”

32

This bipartisan bill builds on

the goals of the SECURE Act, with a number of

additional measures to increase options and protec-

tions for savers and retirees. Among its provisions,

it would require certain newly created plans to

automatically enroll eligible employees at automat-

ically escalating contribution levels, with voluntary

employee opt-out of coverage. The legislation

includes nancial incentives for small businesses to

oer retirement plans and expands savings options

for nonprots. Other provisions in SECURE Act 2.0

increase exibility for savers over 60 as they near

retirement and extend the time individuals can save

by increasing the minimum distribution age to 75.

SECURE Act 2.0 also aims to support low-income

earners to save by enhancing the existing Saver’s

Credit — a federal tax credit for contributions to a

retirement plan. While these measures and those in

the original SECURE Act are steps toward improving

access and savings levels, they are not expected

to signicantly reduce the national access gap.

33

Saver’s Tax Credit

The Saver’s Tax Credit (“Saver’s Credit”) was cre-

ated by Congress in 2001 to encourage savings by

low- and moderate-income taxpayers. Structured

as a tax credit on federal income tax liability, the

Saver’s Credit provides an incentive to save through

its value as a “match” to lower-income savers’

retirement contributions. The amount of the current

credit is based on a taxpayer’s income level, with

the lowest-income earners eligible for a 50% match

to their savings contributions and credit amounts

falling to 20%, 10%, and 0% (above the highest

17

© 2020 Georgetown University Center for Retirment Initiatives What are the Potential Benets of Universal Access to Retirement Savings?

income threshold) as income rises. The maximum

credit amount is capped at $1,000 for an individual

or $2,000 for a married couple ling together.

34

Due to its current structure and administration, the

Saver’s Credit has been underused, limiting its po-

tential to aect the savings behavior of lower-income

households. According to a study by AARP, 9.3%

of returns were eligible for the credit in 2013, but

just 5% claimed it.

35

The credit is complex to apply

for, and credit amounts decrease sharply as income

increases, meaning a small increase in a ler’s in-

come can lead to a signicant decrease in their credit

amount. Importantly, because the credit is non-re-

fundable, households must have an income tax

liability to realize the gains, making many of the low-

est-income earners ineligible. According to a 2006

study from the Congressional Budget Oce, 18% of

lers met the income criteria for the credit but were

ineligible because they had no income tax liability.

36

Many policymakers have suggested enhancements

to the credit to increase its impact for lower-income

savers. The Brookings Institution has suggested

increasing matching rates, increasing eligibility

limits, and making the credit refundable.

37

AARP

has suggested making the credit a savings match

into retirement accounts, and restricting the ability

of savers to withdraw those funds, in addition to

simplifying the ling process and increasing the

eligibility limits and match amounts.

38

Broader reform

proposals have linked the saver’s credit to other

components of the tax code, such as the mortgage

interest deduction, proposing a at credit for all sav-

ings.

39

The proposed SECURE Act 2.0 bill includes

an expansion of the credit, including a higher max-

imum credit amount, increased maximum income

eligibility, and single credit rate rather than a tiered

rate structure.

40

The legislation does not, however,

structure the credit as refundable or institute it as a

deposit directly into retirement savings accounts.

Fintech Can Help Remove Barriers

In addition to policy innovations, the private mar-

ket is responding to changes in the landscape

with the creation of more data-driven technol-

ogy companies focused on providing improved

nancial engagement and performance.

Developing the right technology platforms and

the correct messages can help people under-

stand and use customized tools and products.

Surveys suggest that consumers, particularly

millennials and younger generations, are much

more comfortable with technology companies

as a vehicle for acquiring nancial products.

41

Entrepreneurial nancial technology (“ntech”) rms

deploy technology in innovative new ways that reach

all workers more eectively, including previously

underserved communities, to help them save and

invest for their futures. Advances in technology

focused on nancial applications represent another

potential path to lower cost and complexity and

increased retirement security. The best-known com-

ponent of this approach is through “robo advisors”

that use computerized algorithms to provide nancial

advice and manage portfolios. As these technologies

evolve, they have the potential to provide sound

advice about a broader set of nancial management

strategies, including decumulation, at low cost.

42

These approaches can help build on the initial

wave of digitization and behavioral nudges, such

as auto-enrollment, that have helped increase

quality and lower costs within retirement savings

plans. These eorts still face limitations in expand-

ing access, an uncertain regulatory environment,

and challenges in consumer comfort with these

technologies, with many providers moving to-

ward a hybrid robo and in-person approach.