Handbook

for

Armed Private Security

Contractors in Contingency

Operations

23 February 2010

U

C

O

M

S

J

F

UNITED STATES

JOINT FORCES

COMMAND

Joint Warfighting

Center

Joint Doctrine

Suffolk, Virginia

Joint Concept

Development and

Experimentation

Suffolk, Virginia

U.S. Joint Forces Command

JOINT WARFIGHTING CENTER

116 LAKE VIEW PARKWAY

SUFFOLK, VA 23435-2697

DAN W. DAVENPORT

Rear Admiral, U.S. Navy

Director, Joint Concept Development

& Experimentation, J9

STEPHEN R. LAYFIELD

Major General, U.S. Army

Director, J7/Joint Warfighting Center

MESSAGE TO THE JOINT WARFIGHTERS

As US Joint Forces Command (USJFCOM) continues to interact with the other combatant

commands and Services, we recognize there is no universal solution in dealing with the

complexity of issues associated with armed private security contractors (APSCs) in the joint

force commander’s operational area. Over the last several years, the United States Government

(USG) has done a great deal to address the policy, legal, and contracting issues for improved

oversight and accountability of all contractor services, specifically APSC operations.

Consequently, we developed this pre-doctrinal handbook based upon US Department of Defense

(DOD) instructions, joint doctrine, policies, and contracting language to support joint force

planning, management, and oversight of APSCs now and in future conflicts.

The US military plays an instrumental role in supporting and improving a collaborative

environment between USG agencies, host nation intergovernmental and international

organizations, and private sector companies employing APSCs. The US Office of Secretary of

Defense (OSD) established new polices on managing contractors in support of contingency

operations. New DOD Instructions expanded coverage over defense contractors, their employees,

and all sub-contractors to include US and non-US personnel working under contract with

DOD. In accordance with Fiscal Year 2008 National Defense Authorization Act, DOD

coordinated a memorandum of understanding with the US Department of State (DOS) and the

US Agency for International Development (USAID) to work together in controlling contracting

and contractors in Iraq and Afghanistan.

The APSC project identified, correlated, and assessed relevant DOD trends for utilization

of APSCs. Key stakeholders from the OSD, Joint Staff, DOS, USAID, Department of Justice,

other combatant commands, and military academia worked in concert with USJFCOM to develop

an experimentation campaign. The baseline assessment included research on current practices,

current and proposed doctrine, lessons learned, peer reviewed journals, and other related materials.

Stakeholders validated and supported a limited objective experiment to test the utility of the

handbook in addressing scenarios encountered by the joint force in contingency operations.

The resulting handbook revision applies a whole-of-government effort and identifies solutions

to deconflict, integrate, and in some cases synchronize the joint force and APSC operations.

This handbook also provides examples of “best practices” for establishing and maintaining

coordination, cooperation, and understanding of APSC activities.

Understanding how APSC activities affect joint operations and the evolving effort for

improved communication, management, and coordination between DOD and APSC operations

is vital to the joint force commander. I encourage you to use the information contained within

this handbook and provide feedback to help us capture value-added ideas for incorporation in

emerging joint doctrine.

i

PREFACE

1. Scope

This handbook is a pre-doctrinal publication on planning, integrating, and managing

the employment of “Armed Private Security Contractors” (APSCs) by a joint force

commander (JFC) and staff for a contingency operation. It provides a single collection of

current (2009) work to address the policy, contract, and legal concerns of a joint force

commander and staff.

2. Content

This handbook examines joint doctrine and the current policies, techniques, and

procedures as practiced in the operational theaters. There is continual evolution on this

subject as requirements, procedures, agreements, and best practices adapt to the joint

and interagency community’s needs. This handbook helps bridge the gap between

current practices in the field and existing doctrine. It also offers some considerations for

the future development of APSC-related joint doctrine, training, materiel (logistics),

leadership, education, and facility planning.

3. Development

Development of this handbook was based on information from joint and Service

doctrine, conferences, trip reports, and experimentation. Additional research was

conducted through the wider body of knowledge in civilian and military academic products,

training, and lessons learned. US Government agencies contributed through the whole-

of-government approach to handbook development. Coordination with the leading experts

on policy formulation, understanding legal authorities, contracting, and interagency views

provided the most current direction in this field. Critical stakeholders validated the

experimentation plan, supported the experiment effort, and agreed with the findings.

4. Application

This handbook is not approved doctrine. It is a non-authoritative supplement to

currently limited doctrine to assist JFCs and their staffs in planning and executing activities

involving APSCs. The information herein can also assist the joint community in

developing doctrine and maturing concepts and methods.

5. Contact Information

Comments and suggestions on this important topic are welcome. The USJFCOM

Joint Concept Development and Experimentation Directorate point of contact (POC) is

Maj Arnold Baldoza, USAF, at 757-203-3698 and email: [email protected]. The

Joint Warfighting Center, Doctrine and Education Group, POCs are Lieutenant Colonel

Jeffrey Martin, USAF, at 757-203-6871 and email: jeffrey[email protected]; and Mr. Ted

Dyke at 757-203-6137 and email: [email protected].

ii

Preface

Armed Private Security Contractors in Contingency Operations

Intentionally Blank

iii

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PAGE

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................... v

CHAPTER I

THE JOINT FORCE COMMANDER'S CHALLENGES

• The Contractor Challenge ........................................................................................... I-1

• Management and Coordination of Armed Private Security Contractor Operations ....... I-2

• Issues Addressing Liability for Personnel Misconduct and Incident Management ...... I-3

• Contract Enforcement and Management of Contractors .......................................... I-6

CHAPTER II

LAWS AND POLICIES GOVERNING ARMED PRIVATE SECURITY

CONTRACTORS

• Laws and Policies ..................................................................................................... II-1

• Statutory Requirements ............................................................................................ II-1

• Legal Jurisdiction over Armed Private Security Contractors ................................... II-4

• Combatant Commander Responsibilities .................................................................. II-4

• Area-specific Requirements ..................................................................................... II-6

CHAPTER III

ARMED PRIVATE SECURITY CONTRACTOR PLANNING,

INTEGRATION AND MANAGEMENT

SECTION A. PLANNING FOR THE EMPLOYMENT OF ARMED PRIVATE

SECURITY CONTRACTORS ............................................................... III-1

• Overview and Context ............................................................................................. III-1

• Planning for the Employment of Armed Private Security Contractors .................... III-2

• Establishing Planning Requirements for Armed Private Security

Contractor Support ................................................................................................. III-3

• Contract Support Integration Plan .......................................................................... III-5

• Contractor Management Plan ................................................................................. III-6

• Development of the Armed Private Security Support Contract .............................. III-7

• Department of Defense Operational Contract Support Enablers ............................ III-8

SECTION B. OPERATIONAL INTEGRATION OF ARMED PRIVATE

SECURITY CONTRACTORS ............................................................... III-8

• General ..................................................................................................................... III-8

• Armed Private Security Contractor Integration Initiatives Developed

by United States Central Command ........................................................................ III-9

• Assessing and Balancing Risk to Forces Support................................................ III-11

• Balancing Contracting Best Business Practices with Operational Needs ............ III-11

iv

Table of Contents

Armed Private Security Contractors in Contingency Operations

SECTION C. MANAGEMENT OF ARMED PRIVATE SECURITY

CONTRACTORS ............................................................................... III-12

• Overview ............................................................................................................... III-12

• Primary Responsibilities for Providing Military Management and Oversight ...... III-12

CHAPTER IV

JOINT FORCE COMMANDER COORDINATION WITH NON-DOD ARMED

PRIVATE SECURITY CONTRACTORS

• General ..................................................................................................................... IV-1

• Coordinating Mechanisms ...................................................................................... IV-1

APPENDIX

A Legal Framework for the Joint Force and Armed Private Security

Contractors ...........................................................................................................A-1

B Armed Private Security Contractor Compliance with Joint Force

Commander and Host Nation Requirements ........................................................ B-1

C United States Central Command Contractor Operations Cell

Coordination Procedures ...................................................................................... C-1

D Common Military Staff Tasks When Employing Armed Private

Security Contractors ............................................................................................. D-1

E Standard Contract Clauses That Apply to Armed Private

Security Contractors ............................................................................................. E-1

F Example Military Extraterritorial Jurisdiction Act Jurisdiction

Determination Checklist ....................................................................................... F-1

G References ............................................................................................................ G-1

GLOSSARY

Part I Abbreviations and Acronyms ................................................................... GL-1

Part II Terms and Definitions ............................................................................... GL-5

FIGURES

I-1 Trend of Armed Private Security Contractors in Iraq by Nationality ................ I-2

I-2 Trend of Armed Private Security Contractors in Afghanistan by Nationality .. I-2

II-1 Sample of USCENTCOM Rules for the Use of Force ....................................... II-5

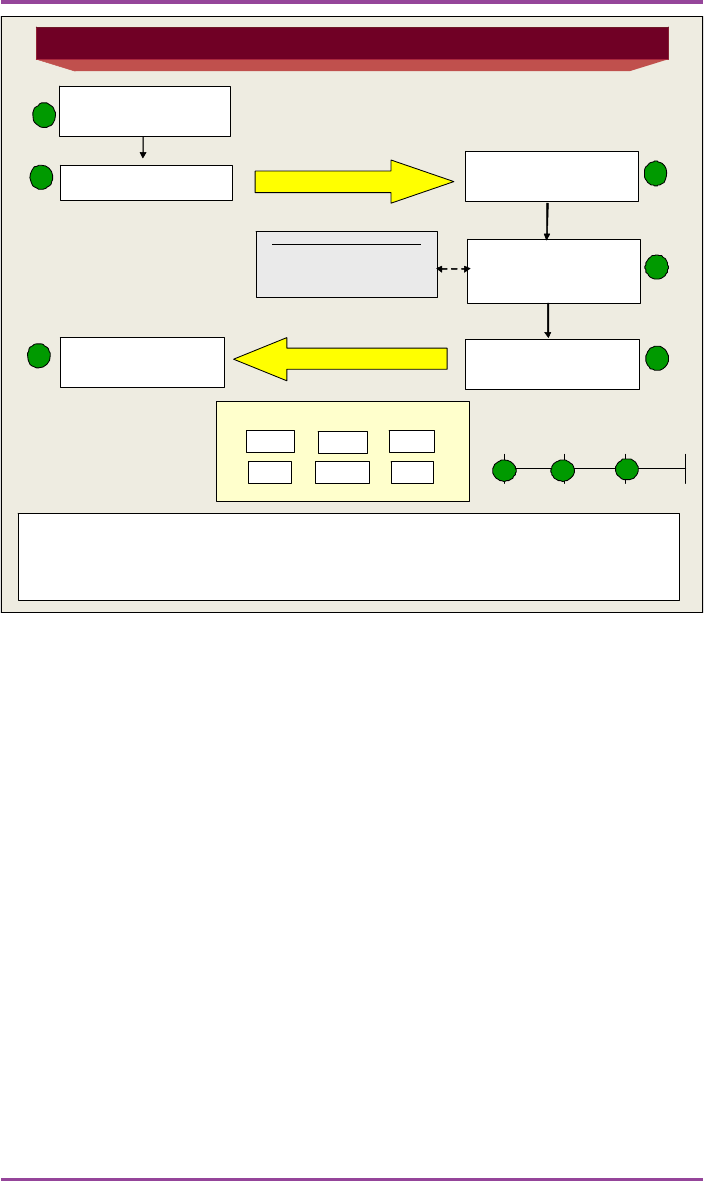

IV-1 DOD Coordination with APSCs in an Operational Area .................................. IV-2

C-1 Contractor Operations Cell Task Organization ................................................. C-2

C-2 Mission Request Form Submission Process .................................................... C-5

C-3 Serious Incident Reporting Process Used in Iraq............................................. C-6

C-4 Serious Incident Report Format ........................................................................ C-7

F-1 Military Extraterritorial Jurisdiction Act Jurisdiction

Determination Checklist ....................................................................................F-1

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

COMMANDER’S OVERVIEW

v

Overview

• Discusses the background, definitions, and status of Armed

Private Security Contractors (APSCs)

• Describes current Department of Defense (DOD) initiatives to

improve the management of APSCs in support of contingency

operations

• Identifies organizations, processes, and procedures for APSC

planning, management, and oversight

This handbook provides

joint force commanders

with needed guidance on

the planning,

employment,

management, and

oversight of armed

private security

contractors (APSCs)

Commanders at all levels

have experienced

challenges in

management,

accountability, incident

management, and

contract enforcement

regarding APSCs.

Recent enactment of laws

and DOD guidance has

established new policies

for managing APSCs in

support of contingency

operations.

This handbook provides the joint force commander (JFC)

and staff with an understanding of laws and policy related

to the planning, employment, management, and oversight

of Armed Private Security Contractors (APSCs) during

contingency operations. While the focus of this handbook

is on contingency operations, most of the limitations and

challenges presented concerning APSCs are applicable

universally.

APSCs are currently supporting US and coalition military

forces by performing critical security functions integral to

the success of US foreign policy objectives and military

operations. However, our ongoing experience with

employing APSCs has revealed a number of continuing

challenges for commanders at all echelons as follows:

• Management of APSC operations to include the

accountability of APSC personnel.

• Incident management procedures and liability for

personnel misconduct.

• Contract enforcement.

The National Defense Authorization Acts (NDAA) of 2007

and 2008 and implementing guidance promulgated in DOD

directives and instructions have revised and established

new policies on the management of contractors, to include

APSCs, in support of contingency operations.

Laws and Policies

JFC Challenges

Armed Private Security Contractors in Contingency Operations

vi

Executive Summary

DOD issuances provide

policy, assign

responsibilities, and

establish procedures for

selecting, training,

equipping, and

accounting for personnel

performing private

security functions.

The JFC and staff should

be familiar with

statutory, legal, and

command requirements

when employing APSCs.

APSCs must not only

comply with the terms of

their contract, but also

all applicable US and

international laws.

The JFC can employ

various management

tools to include

establishment of cross-

functional staff

organizations and the

Of specific interest and application, DODD 3020.41,

Contractor Personnel Authorized to Accompany the U.S.

Armed Forces, defines policy and assigning responsibilities

for program management, DODI 3020.50, Private Security

Contractors Operating in Contingency Operations,

establishes policy, responsibilities, and procedures for

selecting, training, equipping, and accountability of

personnel performing private security functions. DODI

3020.50 also provides procedures for incident reporting,

use and accountability of equipment, guidelines for the use

of force by armed contractors, and a process for

administrative action to punish misconduct by APSC

personnel. This latter Instruction also expands DOD

oversight to include all APSCs operating under United States

Government (USG)-funded contracts during contingency

operations in an area of combat operations, as designated

by the Secretary of Defense.

When employing APSCs, the JFC and the staff should have

a general familiarity with the statutory requirements

regarding the activities and conduct of APSCs, legal

jurisdiction over APSCs, and command-specific requirements

and responsibilities.

Dependent on the terms and conditions of the contract;

processes to plan, manage, and oversee APSCs are designed

to align tasks and performance with the performance work

statements. As contractors, APSCs must be prepared to

perform all tasks stipulated in the contract and comply with

all applicable US and/or international laws.

Combatant commanders regularly update plans to reflect

changes in the operational situation. For contract support

requirements, this process includes the need to recognize

and define the evolving requirements in contractors’

statements of work, awarding of contracts, and supervising

contract execution. In most cases, this will not be a single

service or single function. Rather, it impacts all of the

involved DOD, interagency, and multinational partners.

The JFC can employ various tools to establish organizations,

systems, and mechanisms to assist in various aspects of

managing the activities of APSCs. These management

options range from a joint contractor coordination board as

a policy making body, to a contractor operations cell to

manage daily operations. The roles and contributions of

Planning, Management, and Oversight

vii

Executive Summary

the joint force staff and contracting officers are also a

consideration for JFC management and oversight of APSCs

and their operations.

To improve coordination with non-DOD, USG contracted

APSCs, the JFC must seek the cooperation of a broad range

of parties. The Chief(s) of Mission (COMs) in an

operational area play a key role in organizing non-DOD,

USG participants and is often involved in the planning,

management, and oversight of non-DOD, USG contracted

APSCs. When it comes to non-DOD, USG contracted APSC,

the JFC must work with the COM and country team to

understand respective roles and limitations.

A civil-military operations center provides an option for the

JFC and staff to acquire visibility and situational awareness

of non-USG contracted APSCs present in the operational

area. It also permits the JFC and staff to initiate direct

coordination between controlling entities to plan and

manage mutual APSC support requirements.

This JFC handbook is designed to assist the JFC and staff

in establishing operational and functional relationships with

APSCs within a mutual security environment, and to the

extent possible, provide options to deconflict, synchronize,

and integrate activities for operational success.

detailed assignment of

staff member

responsibilities to

monitor and control the

activities of APSCs.

The JFC must coordinate

with the pertinent Chief

of Mission for the

management and

oversight of non-DOD,

USG APSCs.

The JFC and staff can

employ a civil-military

operations center to

obtain visibility and

situational awareness of

non-USG contracted

APSCs.

This handbook will assist

the JFC and staff in

establishing operational

and functional

relationships with

APSCs.

JFC Coordination with Non-DOD APSCs

Conclusion

Armed Private Security Contractors in Contingency Operations

viii

Executive Summary

Intentionally Blank

I-1

CHAPTER I

THE JOINT FORCE COMMANDER'S CHALLENGES

1. The Contractor Challenge

a. While private contractors have accompanied US forces since the Revolutionary

War, in the past 20 years, there has been an exponential growth in the contractor force.

This change has been most significantly realized in US Central Command (USCENTCOM),

which by the end of the first quarter, fiscal year (FY) 2009, reported its employment of

approximately 259,000 DOD contractor personnel. Of these contractors, nearly 12,000

provided armed security services.

b. Private security contractors can provide significant operational benefits to the

US government (USG). Contractors can often be hired and deployed faster than a similarly

skilled and sized military force. Because security contractors can be employed as needed,

using contractors can allow federal agencies to adapt more easily to changing environments

around the world. In contrast, adapting the military force structure or training significant

numbers of Department of State (DOS) civilian personnel can take months or years.

Security contractors also serve as a force multiplier for the military, freeing up uniformed

personnel to perform combat missions or providing the DOS with the necessary security

capabilities when DOS civilian security forces are unable to cover all commitments. In

some cases, security contractors may possess unique skills that the government workforce

lacks. For example, local nationals hired by USG agencies working overseas may provide

critical knowledge of the terrain, culture, and language of the region. Contractors can be

hired when a particular security need arises and be let go when their services are no

longer needed. Hiring contractors only as needed can be cheaper in the long run than

maintaining a permanent in-house capability.

c. In the past, small numbers of armed private security contractors (APSC) operating

in combatant commander’s (CCDR’s) an area of responsibility (AOR) have not been a

problem. In recent years, however, new problems have arisen with the significant increase

in the number of APSCs. A September 2009 Congressional Research Study, “The

Department of Defense’s Use of Private Security Contractors in Iraq and Afghanistan:

Backgrounds, Analysis and Options for Congress,” summarized the current challenge.

According to DOD, as of June 2009, there were 15,279 private security contractors in Iraq

of which 13,232 were armed (87%). Nearly 88% were third country nationals (TCNs), 8%

were local nationals, the remainder were US citizens. These figures do not include the

thousands of APSCs working for non-DOD agencies, the host nation (HN),

intergovernmental organizations (IGOs) and other international organizations, and private-

sector organizations to include multinational corporations (MNCs). In Iraq there are

reportedly more than 50 private security companies (PSC) employing more than 30,000

armed employees (Figure I-1). In Afghanistan, there are reportedly about 40 licensed

private security companies employing over 20,000 personnel, with another 30 companies

applying for a license. Estimates of the total number of security contractors in Afghanistan

(Figure I-2), including those that are not licensed are as high as 70,000. According to

DOD, since September 2007, local nationals have made up 95% or more of all armed

security contractors in Afghanistan.

I-2

Chapter I

Armed Private Security Contractors in Contingency Operations

d. APSCs differ in significant ways from armed military forces. Military forces are

state employed and controlled by a chain of command and their home nation. APSCs are

privately employed and controlled by contracts. A commander’s ability to direct or

control APSC personnel is limited primarily by the terms of the contract. Only the

Figure I-1. Trend of Armed Private Security Contractors in Iraq by Nationality

Figure I-2. Trend of Armed Private Security Contractors in Afghanistan by

Nationality

I-3

The Joint Force Commander’s Challenges

contracting officer representative (COR) or contracting officer (KO) can direct the

contractor to take any specific action. HN, US federal, and international law also provide

some constraints and restraints, which the commander may leverage to regulate APSC

personnel conduct, but the principal vehicle for the commander to exercise control is the

contract. PSCs operate for capital gain and their employees work for a paycheck. Normally,

neither is guided by US foreign policy objectives.

e. As missions have grown in numbers and complexity, APSC operations have

expanded as well. In addition to providing training for foreign security forces, APSCs are

often engaged in the following security support activities and functions in unsecured

areas:

(1) Static security to protect military bases, housing areas, reconstruction

work sites, etc.

(2) Personal security and protection.

(3) Convoy security.

(4) Provide security for internment operations.

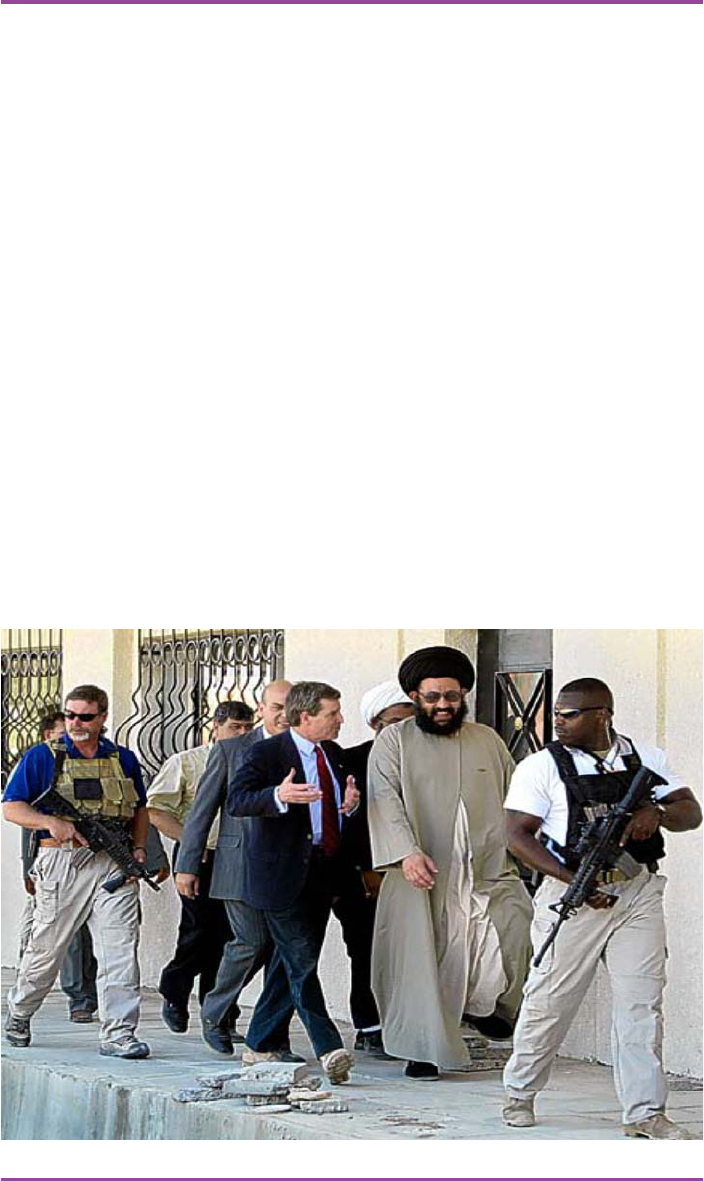

f. With the initiation of Operation IRAQI FREEDOM (OIF), challenges associated

with the management of APSCs have been on the rise. One turning point in particular was

the historically important 2007 incident that involved the APSC organization “Blackwater

Private Security Detail in Iraq

I-4

Chapter I

Armed Private Security Contractors in Contingency Operations

Security” in Nisoor Square in Baghdad, Iraq. An APSC personal security detail that was

escorting a convoy of DOS vehicles, perceived a threatening situation. Confusion led to

escalating the use of force and ended with seventeen Iraqi civilians killed. Local nationals

blamed the Coalition for the shooting. This echoed in the international press coverage

condemning the US for excessive and reckless use of deadly force. This incident illustrates

how the actions of a non-DOD APSC can impact and adversely affect joint force operations.

The “Blackwater” incident further illustrates the lack of oversight the USG has had over

APSCs operating in a JTF commander’s joint operating area and the negative effects that

contractor conduct can have on friendly operations. As a result, the USG undertook a

major effort to create a system to manage APSCs and their conduct, ensure APSCs are

responsive to the needs of their USG sponsors, and ensure the USG has jurisdiction to

prosecute APSCs when necessary.

g. Continuing APSC challenges for commanders at all echelons include:

(1) Management and coordination of APSC operations, including APSC

personnel accountability.

(2) Incident management procedures and liability for personnel misconduct.

(3) Contract oversight.

h. In Iraq, two agencies are responsible for the security of USG employees and

contractors: (1) the US military, which has responsibility for the security of all personnel

under direct control of the CCDR and (2) the DOS, which is responsible for all USG and

nongovernment personnel under Chief of Mission’s (COM’s) authority. With regard to

DOS responsibility, authority is delegated to Embassy Baghdad’s Regional Security Office,

which establishes security policies and procedures. Together, the military and DOS

share responsibility for providing general oversight and coordination of their respective

APSCs, regardless of whether the APSCs perform their services through direct contracts

with the USG or subcontracts with its implementing partners.

2. Management and Coordination of Armed Private Security

Contractor Operations

The JFC must have visibility over all friendly forces operating in the operational

area, including USG and non-USG sponsored APSCs. While the joint force commander

(JFC) can coordinate with the COM to establish common procedures for the registration

of APSC personnel and the management of APSC movements, the JFC has no authority

over non-USG APSCs and only limited authority over non-DOD contracted APSCs. For

establishing visibility over USG-affiliated APSCs, the JFC can establish a contractors

operations cell (CONOC). Described in Chapter III, “Armed Private Security Contractor

Planning, Integration, and Management,” a CONOC functions as a coordinating body,

which identifies and addresses operational concerns regarding movement coordination,

identification procedures, and fratricide avoidance. The CONOC also can work with a

civil military operations center (CMOC) to facilitate establishing visibility over non-USG

APSCs activities.

I-5

The Joint Force Commander’s Challenges

3. Issues Addressing Liability for Personnel Misconduct and Incident

Management

Recently introduced Federal statutes and implementing DOD policy guidance have

significantly expanded the JFC’s investigatory and criminal prosecution authority over

misconduct by individual employees of DOD affiliated APSCs. When combined with

specific contract language addressing general standards of conduct for APSC employees,

the JFC has a far broader range of measures that can be employed to enforce individual

behavioral standards and even penalize the contractor for individual misdeeds. As

described in Chapter II, “Laws and Policies Governing Armed Private Security

Contractors,” these initiatives have provided JFCs with leverage to punish specified

contractor misconduct. However, these statutes and policies only apply to DOD

contractors. For non-DOD APSCs, the JFC must rely on the laws of the respective

contracting nation and the HN to punish misconduct. At a minimum, the JFC should

establish incident management and reporting procedures for the command, which under

the terms of DOD contracts, apply to the APSCs.

4. Contract Enforcement and Management of Contractors

a. A commander’s ability to direct or control APSC personnel is limited by the terms

of the contract. At a minimum, an APSC contract will advise the contractors on the laws

and regulations governing the import of their weapons into the country. It will specify

the contractor’s responsibilities to instructions from the chain of command (usually

published in the form of fragmentary orders (FRAGORDs)), require APSC employees to

understand and accept terms for carrying weapons when on- and off-duty, describe the

types of weapons that can be carried, stipulate how an APSC is allowed to carry their

weapons, provide guidance on the use of force, and remind contractors that MEJA and/

or the UCMJ apply to specified acts of misconduct. Ideally the JFC should obtain the

contracts of all the DOD-affiliated contractors in the operational area through the theater

contracting organization structure. Familiarity with the terms of an APSC’s contract will

facilitate the management of DOD affiliated contractors by the command’s KOs and

CORs. For non-DOD, USG affiliated APSCs, specific information on the contract provisions

can usually be obtained by coordination with the American Embassy (AMEMB),

specifically the regional security officer (RSO).

b. The goal of a well-written contract and its supporting enforcement/coordination

mechanism is to ensure the activities of DOD contracted APSCs are integrated in and

synchronized with joint operations and there are established standards for the training

and conduct of APSCs. At a minimum, when dealing with APSCs employed by non-USG

entities, the JFC can seek to use the US model as a suggested standard for adoption by

those third parties.

I-6

Chapter I

Armed Private Security Contractors in Contingency Operations

Intentionally Blank

II-1

CHAPTER II

LAWS AND POLICIES GOVERNING ARMED PRIVATE

SECURITY CONTRACTORS

“Armed Private Security Contractors are first and foremost contractors who must

comply with all Department of Defense requirements concerning visibility,

deployment, and redeployment requirements; they must adhere to theater

management procedures; and must abide by applicable laws, regulations, policies,

and international agreements.”

Report of the Special Inspector General for the Reconstruction of Iraq

August 2008

1. Laws and Policies

A number of federal laws and implementing DOD Directives (DODD) and Instructions

(DODI) provide specific guidance on the employment of contingency contractors and

APSCs. (Note: Additional detail is provided in Appendix A, “Legal Framework for the

Joint Force and Armed Private Security Contractors.”) While the staff judge advocate

and contracting organizations have expertise in dealing with specific issues relating to

the contract and the application of US federal law to individual APSC employees, the JFC

and staff should have a general familiarity with the following: statutory requirements

regarding the activities and conduct of APSCs; the extent of their legal jurisdiction over

individual APSC’s conduct; theater-specific requirements and command responsibilities

that have been established by the CCDR; and AOR-specific requirements and command

responsibilities established by the CCDR and supplemented, as required, by the

subordinate JFC.

2. Statutory Requirements

The following federal laws and DODD/DODI provide the JFC with guidance to plan

and manage APSC contracts.

a. FY 2008 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA), Section 861. The Act

requires DOD, DOS, and USAID, the leading agencies that employ APSC abroad, to

establish a memorandum of understanding (MOU) addressing contracting procedures

and contractors in Iraq and Afghanistan. In July 2008, DOD, DOS, and USAID agreed

and signed the required MOU specifying each agency’s roles and responsibilities

concerning contracts in the two countries; established responsibilities, procedures, and

coordination for movements of APSCs in the two countries; and agreed to a common

database for contract information. DOD developed the Synchronized Pre-deployment

and Operational Tracker (SPOT) and designated it as the contractor management and

accountability system to provide a central source of contingency contractor information

to fulfill this last requirement.

b. FY 2008 NDAA, Section 862. This section requires DOD and DOS to develop

regulations for the “selection, training, equipping, and conduct of personnel performing

II-2

Chapter II

Armed Private Security Contractors in Contingency Operations

private security functions under a covered contract in an area of combat operations.”

These regulations are normally incorporated as specific requirements in the APSC’s

contract and include:

(1) A process for registering, processing, accounting for, and keeping

appropriate records of personnel performing APSC function in an area of combat

operations.

(2) A process for authorizing and accounting for weapons carried by personnel

providing private security functions.

(3) A process for registration and identification of armored vehicles, helicopters,

and other vehicles used by APSCs.

(4) An incident reporting procedure.

(5) A process for independent review of incidents.

(6) Requirements for qualification, training, and screening, including

background checks.

(7) Knowledge of the rules for the use of force (RUF).

(8) Development of specific contract clauses to require compliance with these

goals and objectives.

c. DODI 3020.41, Contractor Personnel Authorized to Accompany the US Armed

Forces, October 3, 2005 (under revision). This DODI provides the overarching policy

for DOD to:

(1) Implement appropriate contractor planning, visibility, deployment, and

redeployment requirements; adhere to theater management procedures; abide by

applicable laws, regulations, policies, and international agreements; and use contractor

support only in appropriate situations consistent with the Defense Federal Acquisition

Regulation Supplement (DFARS).

(2) Implement DODI 3020.41 in operations plans (OPLAN) and operations

orders (OPORD) and coordinate any proposed contractor logistic support arrangements

that may affect the OPLAN/OPORD with the affected geographic combatant commanders

(GCCs).

(3) Ensure contracts clearly and accurately specify the terms and conditions

under which the contractor is to perform, describe the specific support relationship between

the contractor and DOD, and contain standardized clauses to ensure efficient deployment,

visibility, protection, authorized levels of health service and other support, sustainment,

and redeployment of contingency contractor personnel.

(4) Develop a security plan for protection of contingency contractor personnel

in locations where there is not sufficient or legitimate civil authority and the commander

II-3

Laws and Poicies Governing Armed Private Security Contractors

decides it is in the interests of the USG to provide security, because the contractor cannot

obtain effective security services, such services are unavailable at a reasonable cost, or

threat conditions necessitate security through military means.

(5) Ensure that contracts for security services shall be used cautiously in

contingency operations where combat operations are ongoing or imminent. Authority

and armament of contractors providing private security services will be set forth in their

contracts.

(6) Maintain by-name accountability of all APSC personnel and contract

capability information in a joint database. This database shall provide a central source of

personnel information and a summary of services or capabilities provided by all external

support and systems support contracts. This information shall be used to assist planning

for the provision of force protection, medical support, personnel recovery, and other

support. It should also provide planners an awareness of the nature, extent, and potential

risks and capabilities associated with contracted support in the operational area. Note:

In January 2007, SPOT was designated as the DOD database to serve as the central

repository for all information for contractors deploying with forces and contractor

capability information.

d. DODI 3020.50, Private Security Contractors Operating in Contingency

Operations, July 22, 2009. This is the latest guidance that directly applies to APSCs

employed in contingency operations outside the United States. DOD policy:

(1) Requires the selection, training, equipping, and conduct of APSC personnel

including the establishment of appropriate processes to be coordinated between the

DOD and DOS.

(2) Requires GCCs to provide APSC guidance and procedures tailored to the

operational environment in their (AOR. Specifically, they must establish the criteria for

selection, training, accountability, and equipping of such APSC personnel; establish

standards of conduct for APSCs and APSC personnel within their AOR; and establish

individual training and qualification standards that shall meet, at a minimum, one of the

Services’ established standards. Additionally, through the contracting officer, ensure

that APSC personnel acknowledge, through the APSC’s management, their understanding

and obligation to comply with the terms and conditions of their covered contracts.

Furthermore, issue written authorization to the APSC identifying individual APSC

personnel who are authorized to be armed. RUF, developed in accordance with Chairman

of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Instruction 3121.01B shall be included with the written

authorization.

(3) Recognizes that the relevant COM is responsible for developing and

issuing implementing instructions for non-DOD APSCs and their personnel consistent

with the standards set forth by the GCC. The COM has the option to instruct non-DOD

APSCs and their personnel to follow the guidance and procedures developed by the GCC

and/or subordinate JFC. Note: Interagency coordination for investigation, administrative

penalties, or removal from the theater of non-DOD affiliated APSCs for failure to fulfill

their contract requirements may be included in these instructions.

II-4

Chapter II

Armed Private Security Contractors in Contingency Operations

(4) Additionally, DODI 3020.50 requires GCCs to develop and issue

implementing procedures for the selection, training, accountability, and equipping of

such APSC personnel and the conduct of APSCs and APSC personnel within their AOR.

In consultation with the COM in designated areas of combat operations, these requirements

also are shaped by considerations for the situation, operation, and environment.

3. Legal Jurisdiction over Armed Private Security Contractors

There are four ways that an individual contractor can be prosecuted for misconduct:

a. Where the HN has a functioning legal infrastructure in place and in the absence

of a SOFA that includes protections for DOD affiliated APSCs, the civil and criminal laws

of the HN take precedence. If the HN waives jurisdiction, then US laws regarding criminal/

civil liability will have precedence.

b. With the passage of Section 552, “Clarification of Application of Uniform Code of

Military Justice During a Time of War,” of the John Warner National Defense Authorization

Act (NDAA) for Fiscal Year 2007, commanders are authorized court martial jurisdiction

over certain offenses committed outside of the Continental United States by contractors

employed by or accompanying US forces in a declared war or contingency operation.

c. If an APSC employee has not been prosecuted under the HN’s legal system or

under the Uniform Code of Military Justice (UCMJ), that person, after being brought to

the US, can be tried in US Federal Court under the “Military Extraterritorial Jurisdiction

Act” (MEJA), 18 United States Code, Section 3261. MEJA allows a JFC to bring criminal

charges against US contractors working for DOD or in support of a DOD mission; however,

it only applies to felonies - offenses punishable by at least one year in prison.

d. Certain US federal statutes have extraterritorial application regardless of the

application of MEJA or the UCMJ. For example, certain acts of war profiteering, torture,

certain false statements by a US citizen, theft of federal property by US citizens abroad,

and certain fraud, human trafficking, counterfeiting, and forgery offenses can subject the

alleged offender to the jurisdiction of the US courts regardless of the seriousness of the

offense.

4. Combatant Commander Responsibilities

a. CCDRs have responsibility for geographic areas or specific worldwide functions.

While DOD has published DODIs and DODDs establishing general requirements, the

CCDRs must tailor their implementing regulations, orders, directives, and instructions to

fit their unique requirements for contingency operations and the employment of APSCs.

b. CCDR Responsibilities

(1) Registering and Accounting for Personnel. When the CCDR considers

using APSCs, there is a requirement to register and account for personnel assigned to the

various contracts implemented within the AOR. The current SPOT system allows the

command to register and track personnel as they in-process through a centrally controlled

II-5

Laws and Poicies Governing Armed Private Security Contractors

deployment center, and issue documentation that will establish that individual’s status

and authorize government support for each individual associated with the GCC’s forces

in a theater. SPOT provides a web-based database tool to track all types of contractor

personnel and contractor expertise and capabilities within a theater. This system also

tracks contractor operated armored vehicles, helicopters, and other vehicles. Contracting

officers (KOs) must keep track of, and account for, contractor personnel while deployed

in support of the force.

(2) Verifying Eligibility and Granting Permission to Arm Contractors. When

there is a requirement to arm contractor personnel, a review by the staff judge advocate

(SJA) ensures the agreement follows US and HN law and DOD policies. At a minimum

contractors will be required to be trained on specifically authorized weapons to Service

established standards before they are granted authorization to carry weapons. Contractor

weapons training will include the command’s established procedures for reporting of

suspected incidents.

(3) Establishing RUF. Established at the combatant command level, RUF

require a certain amount of restraint. As a result, APSC personnel must be thoroughly

familiar with the application of RUF in various scenarios. RUF need to be developed and

implemented in the contract and are usually modified as the situation changes. The JFC,

through the KOs, will certify that APSCs are following the RUF. Figure II-1 is an example

of USCENTCOM RUF for APSCs in Iraq.

Figure II-1. Sample of USCENTCOM Rules for the Use of Force.

SAMPLE OF USCENTCOM RULES FOR THE USE OF FORCE

USCENTCOM

RULES FOR THE USE OF FORCE BY CONTRACTED

SECURITY IN IRAQ

NOTHING IN THESE RULES LIMITS YOUR INHERENT

RIGHT TO TAKE ACTION NECESSARY TO DEFEND

YOURSELF

1. CONTRACTORS: A re nonc om batan ts, you may n ot e ngage in offe nsi ve

operat ions with Co al ition Forces. You alwa ys retain y our ab ility to exerc ise sel f-

defense against hostile acts or demonstrated hostile intent.

2. CONTRACTED SECURITY FORCES: Cooperate with Coalition

an d Ir aqi Pol ic e/Secu rity Forc es and comp ly wit h th eater forc e p rot ecti on pol ic ie s.

Do not av oi d or ru n Co al it ion or Iraqi Po li ce/S ecu ri ty Forc e che ckpoi nts. If

authorized to carry weapons, do not aim them at Coalition or Iraqi Police/Security

Forces.

3. USE OF DEADLY FORCE: Deadly force is that force, which one

reasonably believes will cause death or serious bodily harm. You may use

NECESSARY FORCE, up to and including deadly force against persons in the

fo ll owi ng c irc um st ance s:

a. In self-defense,

b. In defense of facilities and persons as specified in your contract,

c. To prevent life threatening offenses against civilians,

d. In defe ns e o f C oal itio n- appr ove d p rope rty spec ified i n y ou r cont ract

4. GRADUATED FORCE: You will use the reasonable amount of force

ne cessa ry. The f ollo win g are som e tec hn iqu es you ca n u se, if t he ir u se wil l no t

unnecessarily endanger you or others.

a. S HOUT : v erbal wa rn ings to HA LT in na tiv e lan guag e

b. S HOW: yo ur wea p on an d d em onstrat e inten t t o us e i t.

c. SHOOT: to remove threat only when necessary

USCENTCOM

RULES FOR THE USE OF FORCE BY CONTRACTED

SECURITY IN IRAQ

NOTHING IN THESE RULES LIMITS YOUR INHERENT

RIGHT TO TAKE ACTION NECESSARY TO DEFEND

YOURSELF

5. IF YOU MUST FIRE YOUR WEAPON:

a. Fi re o nly aime d s ho ts,

b. Fire with due regard for the safety of innocent bystanders,

c. Immediately report the incident and request assistance.

6. CIVILIANS: Treat Civilians with Dignity and Respect

a. Make every effort to avoid civilian casualties,

b. You m ay s top, d etain , se arc h, and d is arm c ivi li an perso ns if req uire d fo r

your safety or if specified in your contract,

c. Civilians will be treated humanely,

d. Detained civilians will be turned over the Iraqi Police/Security or Coalition

Forces as soon as possible.

7. WEAPONS POSSESSION AND USE: Possession and use of

weapons must be authorized by USCENTCOM and must be specified in your

contract.

a. You must carry proof of weapons authorization,

b. You wi ll mai nta in a cu rre nt wea pon s tr ai ni ng rec or d,

c. You may possess and use only those weapons and ammunition for which

you are qualified and approved,

d. You m ay not j oi n C o al ition Forces in co mbat op erat ion s,

e. You must follow Coalition weapons condition rules for loading and cleaning.

II-6

Chapter II

Armed Private Security Contractors in Contingency Operations

(4) ROE and RUF should not be used interchangeably. Generally, ROE refers

to rules of force during military combat operations while RUF usually refers to the use of

force required while conducting security or noncombat operations.

(a) ROE is the authority to use up to lethal force to engage an enemy of

the State, and the source of authority is a State’s inherent right to defend itself and

provide national security. For the US military, ROE must be approved by the chain of

command, commencing with the President and Secretary of Defense. Subordinate

commanders may further limit the rules, but may not expand them, and in no case can the

rules deprive military personnel of their inherent right of self defense.

(b) RUF is the term applied to personnel who are authorized to use force

to accomplish their mission to enforce laws, maintain peace and security, and protect the

civilian population. The source of this authority is the duty of the State to protect its

citizens.

(c) ROE apply only to military operations under proper orders from the

SecDef through the chain of command. RUF apply to security type operations; therefore,

if the APSC is performing law enforcement operations, then the RUF would apply. Under

a typical RUF the right of self-defense is inherent and may be resorted to for protection

from a hostile act or the display of a hostile intent indicating an imminent attack.

Additionally, absent a hostile act or intent, the right of self-defense does not authorize

the use of force to protect government property, and the assistance of security forces

should be sought. Furthermore, the use of force must be proportional to the threat in

intensity, duration, and magnitude based on facts known, with due care for third parties

in the vicinity.

(d) Contractors may be used for a variety of missions, many of which do

not involve the likely use of force to accomplish a mission but are nonetheless high risk.

These activities include supporting field operations, conducting surveillance programs,

providing police training and mentoring, and providing corrections/border patrol training.

In high risk situations, these contractor personnel may be authorized to carry arms for

self-defense.

(e) Contractors should not be asked or offer to assume inherently military

missions just because they may be armed or because they have particular knowledge or

skills outside those called for in the scope of their contracts, as it is not a proper delegation

of such duties. For example, a security team with the mission to protect a contractor,

should not ask the contractor to lead a convoy or man one of the weapons other than for

the purpose of self-defense.

5. Area-specific Requirements

a. In contingency operations, JFCs are responsible for ensuring, through contract

management teams, that contractors comply with orders, directives, and instructions

issued by the CCDR and the JFC especially those relating to force protection, security,

health, safety, and relations and interaction with local nationals. In circumstances where

DOD contractor personnel are authorized to be armed, commanders and contracting

II-7

Laws and Poicies Governing Armed Private Security Contractors

officials are responsible for ensuring they comply with specific CCDR and subordinate

JFC guidance for the operational area, including ROE and RUF, use of weapons in self-

defense, and local license requirements. Additional information is included in Appendix

B, “Armed Private Security Contract Compliance with Joint Force Commander and Host

Nation Requirements.”

b. While most AOR-specific contract requirements will have been identified early in

the planning process for inclusion in the base contract, the contract also should provide

a vehicle for updating/modifying requirements as the situation dictates. The JFC should

coordinate procedures with the respective KOs to develop and promulgate these changes

to the affected contractors. For example in the USCENTCOM AOR, the command uses

FRAGORDs to effect changes. As discussed in the following chapter, JFCs should

ensure promulgation of appropriate requirements for arming contract security personnel

and investigate use of force incidents.

II-8

Chapter II

Armed Private Security Contractors in Contingency Operations

Intentionally Blank

III-1

CHAPTER III

ARMED PRIVATE SECURITY CONTRACTOR PLANNING,

INTEGRATION, AND MANAGEMENT

SECTION A. PLANNING FOR THE EMPLOYMENT OF

ARMED PRIVATE SECURITY CONTRACTORS

1. Overview and Context

a. The 2008 Congressional Research Service (CRS) Report to Congress, Private

Security Contractors in Iraq: Background, Legal Status, and Other Issues, 25 August

2008, identified the following key issues and concerns influencing APSC planning,

integration, and management:

(1) The United States is relying heavily on private firms to supply a wide

variety of services…including security. From publicly available information, this is

apparently the first time that the United States has depended so extensively on contractors

to provide security in a hostile environment.

(2) Private contractors contribute an essential service to US and international

efforts to bring peace. Nonetheless, the use of armed contractors raises several concerns,

including transparency and accountability.

(3) The lack of public information on the terms of the contracts, including their

costs and the standards governing hiring and performance, make evaluating their efficiency

difficult. The apparent lack of a practical means to hold contractors accountable under

US law for abuses and other transgressions, and the possibility that they could be

prosecuted by foreign courts, is also a source of concern.

b. This CRS report further explains that questions often arise when a federal agency

hires private persons to perform “inherently governmental functions,” which Congress

in 1998 defined as “so intimately related to the public interest as to require the performance

by Federal government employees (FAIR Act of 1998). DOD implementation of DFARS

does not prohibit the use of contractors for security, but limits the extent to which contract

personnel may be hired to guard military institutions and provide personnel and convoy

security. DOD subsequently clarified and amended DFARS to authorize APSCs to use

deadly force “only when necessary to execute their security mission to protect assets /

persons, consistent with the mission statement contained in their contract.” This rule

establishes that:

“It is the responsibility of the combatant commander to ensure that the private

security contract mission statements do not authorize the performance of any

inherently Governmental military functions, such as preemptive attacks, or any

other types of attacks. Otherwise, civilians who accompany the US Armed Forces

lose their law of war protections from direct attack if and for such time as they take

a direct part in hostilities.”

c. Acknowledging, “without private contractors, the US military would not have

sufficient capabilities to carry out operations,” the CRS Report recognizes “potential

III-2

Chapter III

Armed Private Security Contractors in Contingency Operations

downsides to (this) force multiplier argument.” Citing important concerns, it questions

whether the use of private security contractors may adversely affect:

(1) Military force structure suggesting that a competing private sector could

deplete the military of highly trained security personnel.

(2) US military missions when APSCs disregard the sensitivities of and

consequences for the people of the HN.

(3) Military flexibility as commanders do not exercise command and control of

APSCs.

(4) Reliability and quality of APSCs as the demand for security services

increases.

d. The following considerations are integral to the basic relationship between the

commander and the APSCs, and provide general guidance when drafting the overall

terms of a contract:

(1) APSCs are required to perform all tasks identified within the performance

work statements and all provisions defined in the contract. As contractors, APSCs must

be prepared to perform all tasks stipulated in the contract and comply with all applicable

US and/or international laws.

(2) APSC employees may be subject to court-martial jurisdiction in time of war

or while participating in a contingency operation.

(3) Even though APSCs are armed, when deployed, the JFC has a continuing

obligation to provide or make available force protection and support services

commensurate with those authorized by law.

(4) APSCs accompanying the US Armed Forces may be subject to hostile

actions. If captured, an APSC’s status will depend upon the APSC’s precise activity at

the time of capture, the applicability of the Geneva Convention Relative to the Treatment

of Prisoners of War (GC III), the Geneva Convention Relative to the Protection of Civilian

Persons in Time of War (GC IV), the type of conflict, applicability of other bodies of

international law and any relevant international agreements, and the nature of the hostile

force (state-based armed force, irregular force, paramilitary force, terrorist group, etc.).

2. Planning for the Employment of Armed Private Security

Contractors

a. For each APSC mission area, effective planning and integration significantly

improves the potential to successfully manage and implement APSC operations. APSCs

typically support four mission areas:

(1) Static security to protect military bases, housing areas, reconstruction

work sites, etc.

III-3

Armed Private Security Contractor Planning, Integration, and Management

(2) Personal security and protection.

(3) Convoy security.

(4) Security for internment operations.

b. It is worth noting that the fourth mission area is a relatively recent and expanding

role for APSCs. These contracts for custodial security, support for detention operations,

riot control, and related missions, significantly impact associated APSC performance

work statements and RUF.

c. Qualified and well-trained CORs and KOs need to be involved from the beginning

of the JFC planning processes to identify the requirements for APSC support. Involvement

of the joint force SJA or legal counsel is crucial and fundamental to effective planning for

APSC support. Early participation in JFC mission analysis yields a clearer understanding

of contract requirements and more efficient allocation of JFC and APSC personnel and

resources.

d. In accordance with DODI 3020.50, CORs need to be identified for US government

private security contractors operating in a designated area of combat operations. This

DODI prescribes the selection, accountability, training, equipping, and conduct of

personnel performing private security functions under a covered contract in a designated

area of combat operations for both DOD and DOS APSCs. It also prescribes incident

reporting, use of and accountability for equipment, RUF, and a process for the discipline

or removal, as appropriate, of USG private security contractor personnel. The DODI

responds to requirements of section 862 of the FY 2008 NDAA.

3. Establishing Planning Requirements for Armed Private Security

Contractor Support

a. The CCDR provides specific guidance on arming contractor personnel and private

security contractors in the AOR through DOD and theater-specific policies, FRAGORDS,

and other authoritative guidance.

b. During the mission analysis, the following general conditions and requirements

regarding contracts and contractor personnel should be considered:

(1) Private security contractor personnel are not authorized to participate in

offensive operations and must comply with specific RUF. Under these RUF, private

security contractor personnel are authorized to use deadly force only when necessary in:

self-defense, defense of facilities/persons as specified in their contract; prevention of

life-threatening acts directed against civilians; or defense of JFC-approved property

specified within their contract. The JFC will issue, to approved private security contractor

personnel, a weapons card authorizing them to carry a weapon. This weapons card also

contains the guidance for the RUF and the contractor personnel’s signature acknowledging

the difference between the RUF and ROE.

(2) Private security contractor personnel must be properly licensed to carry

arms in accordance with HN law and must receive JFC approval of their operations.

III-4

Chapter III

Armed Private Security Contractors in Contingency Operations

(3) In addition to properly authorized Status of Forces Agreements (SOFAs),

the status of Stationing Agreements (SA) can be discussed between the United States

and a HN. A stationing agreement can establish joint committees to review existing APSC

policies and to develop new policies and procedures. Committee members include

representatives from the HN Ministry of Interior and the AMEMB. These committees can

discuss and implement the following:

(a) Licensing of contractors.

(b) Registration of firearms and personal security weaponry.

(c) Vehicle registration.

(d) Licensing of pilots and aircraft related to personnel and security

operations.

(e) Customs, duties, tariffs, taxation and inspections.

(f) Entry, exit procedures and use of DOD assets to transport members of

the US Forces, DOD civilian component, US contractors, AMEMB personnel, and other

members of the Coalition.

(g) DOD contractor personnel armed by DOD authorities must report

any use of force, including the firing of a weapon. This requirement and the required

information to be submitted, or references imposing the specific requirements, are identified

within the terms of the contract.

Note: By incorporating these requirements in the contract’s basic provisions (or subsequent

amplifying directives), the JFC can minimize the opportunities for problems related to contractor

performance and/or misconduct.

c. APSC requirements also shape specific measures of performance and resulting

performance work statements (PWS) to include the duration of support, and the USG’s

requirements to provide subsistence and care for APSCs. Ultimately, the result of this

process yields an actual cost-benefit analysis of proposed APSC support, which serves

to appropriately scope and determine the worth of APSC costs/effort to continue with the

contract.

d. Contracting for APSC support incurs higher-than-average levels of risk given the

potentially profound consequences of their actions. Other considerations include: the

appearance or perception of APSCs as mercenaries; RUF and the escalation of force

issues; back-up plans for corrective action should a contractor default; questions of

human trafficking; and how to synchronize, integrate, essential services, and manage the

APSCs (as described in JP 4-10, Operational Contract Support, Chapter IV).

e. During mission analysis, establishment of a working group is recommended to

consider the employment of APSCs. This working group should include the following

joint force staff representatives or members:

III-5

Armed Private Security Contractor Planning, Integration, and Management

(1) J-1, Personnel Directorate;

(2) J-2, Intelligence Directorate;

(3) J-3, Operations Directorate;

(4) J-4, Logistics Directorate;

(5) J-5, Plans and Policy Directorate;

(6) J-6, Command, Control, and Communications Directorate;

(7) SJA;

(8) Provost Marshal Office (PMO);

(9) Civil Affairs (CA);

(10) PA;

(11) Security Manager;

(12) Staff Surgeon;

(13) Applicable contracting authorities; and

(14) Resource Manager or Comptroller.

f. With known contract support requirements and the subsequent development of

each PWS, the contract planning process needs to recognize and define evolving

requirements that may affect a contractor’s PWS along with the procedures to award the

contract and supervise its execution.

Note: Planning considerations for APSC support explained in JP 4-10 includes the development

of the contract support integration plan (CSIP).

4. Contract Support Integration Plan

a. In all operations where there will be a significant use of contracted support, the

supported GCCs and their subordinate commanders and staffs must ensure that this

support is properly addressed in the appropriate OPLAN/OPORD. Accordingly, a CSIP is

developed by the logistics staff contracting personnel, assisted by the lead Service (if a

lead Service is designated). Additionally, each Service component should publish its

own CSIP seeking integration and unity of effort within the supported GCC’s CSIP. The

CSIP defines key contract support integration capabilities to include command and control

(C2) relationships, cross functional staff organization (e.g., board, center, cell) requirements,

theater business clearance policies, etc., necessary to execute subordinate JFC contract

support integration requirements. Using the guidance provided in the CSIP, requiring

III-6

Chapter III

Armed Private Security Contractors in Contingency Operations

activities have the basis for defining, vetting and prioritizing joint force requirements, to

include the need for APSC support.

b. Normally, the CSIP is developed by the J-4 contracting personnel, but this effort

may be assisted by the lead Service (if a lead Service is designated). Additionally, each

Service component should publish its own CSIP seeking integration and unity of effort

within the supported GCC’s CSIP. Close coordination with J-3, J-5, CA, financial

management, and legal support is essential to the development of the CSIP. JP 4-10

provides a detailed discussion of the CSIP development process and a contracting support

planning checklist can be found in its Appendix E.

5. Contractor Management Plan

a. While the CSIP is focused on how we will acquire and manage contracted support,

contractor management planning is focused on the government obligations under the

terms and conditions of the contract to provide support (e.g., accountability, force

protection, government furnished equipment (GFE)) to contractor personnel. This

includes developing policies and procedures required to ensure proper integration of

contractor personnel into the military operations.

b. IAW DOD policy, the supported GCC and subordinate JFC must identify operation

specific contractor management policies and requirements for inclusion in the OPLAN/

OPORD. These requirements include, but are not limited to:

(1) Compliance with operationally specific contracting polices to include

Service, multinational, and HN requirements and guidance;

(2) Contractor-related deployment, theater reception, accountability, and

strength reporting;

(3) Operations security plans and restrictions, force protection, and personnel

recovery;

(4) Contractor personnel services support;

(5) Medical support; and

(6) Redeployment requirements.

c. For each operation, the GCC should publish a contractor management plan

(CMP). The CMP identifies the theater’s specific contractor personnel and equipment

requirements for the JFC(s), Service components, joint theater support contracting

command (if established), special operations forces, and Defense Logistics Agency to

incorporate into applicable contracts as required. Supporting the GCC’s CMP, the JFC(s)

and Service components should prepare CMPs that provide added, specific details.

III-7

Armed Private Security Contractor Planning, Integration, and Management

d. While the subordinate JFC-level CSIP is coordinated and written by the J-4 or

designated lead Service contracting staff, there is no single primary or special staff officer

responsible to lead the contractor management planning effort. By its very nature,

contractor management integration-related planning responsibilities cross all primary

and special staff functional lanes. To address this situation, the JFC should consider

establishing a contractor management integration working group to ensure the various

contractor management challenges are addressed and synchronized across all primary

and special staff lines.

6. Development of the Armed Private Security Support Contract

a. The culmination of the requirements process leads to the development of the

terms of the contract. While each AOR will develop a contract tailored to their particular

circumstances, the tasks will generally include supplementing internal operations at entry

control points, manning perimeter towers, securing selected facilities, providing convoy

security, providing personal protection for select individuals, providing armed escorts

for local national laborers, maintaining a liaison cell at selected headquarters sites, and

any other internal security services as determined by the command. It will always contain

a specific prohibition against engaging in offensive operations. A current example of an

APSC contract is USCENTCOM’s “Theater Wide Internal Security Services” (TWISS).

b. The USCENTCOM TWISS contains detailed requirements for the training and

qualifications of APSC individual employees. For example, it specifies that:

(1) The security contract companies will be expected to supply guards,

explosive ordnance detection dog handlers (and working dogs), screeners, interpreters,

supervisors, medical officer, and other managerial personnel.

(2) The security guards must be at least 21 years old and speak English well

enough to give and receive situational reports. They may be expatriates or local nationals.

They must be qualified on 9mm, 5.56 and 7.62 caliber weapons, and be able to fulfill work-

weeks of not more than 72 hours.

(3) Employees will be expected to fully understand the differences between

the law of war (a.k.a, law of armed conflict (LOAC)), RUF, and ROE.

(4) Contractors will obtain a signed written acknowledgement from each of

their employees authorized to bear weapons that they have been briefed on the law of

war, RUF, and the differences between ROE and RUF. The TWISS also makes it clear that

RUF controls the use of weapons by contractors employed the USG and that the

contractor may NOT use ROE at any time for use of force decisions.

c. The TWISS is a very detailed document that covers all aspects of the APSC’s

relationships with the USG. The terms of the TWISS are used by the KO and the COR

when determining the contractor’s compliance with the terms of the contract – non-

III-8

Chapter III

Armed Private Security Contractors in Contingency Operations

compliance usually results in a range of penalties. Example of the TWISS’s contract

language can be found in Appendix E, “Standard Contract Clauses that Apply to Armed

Private Security Contractors.”

7. Department of Defense Operational Contract Support Enablers

a. The NDAAs of 2007 and 2008, mandated that DOD develop joint policies

addressing the definition of contract requirements and establishing coherent contingency

management programs. Implementing actions by DOD included establishing the Joint

Contingency Acquisition Support Office (JCASO), and co-locating fourteen joint

operational contract support planner (JOCSP) positions with select combatant commands

to improve operational contract support. The JCASO and JOSCP could also be leveraged

to assist in planning, integrating, and managing APSCs. These enablers should be

utilized by JFCs and joint force staff planners early, often, and throughout the planning

process.

b. JCASO

(1) The JCASO, assigned to the Defense Logistics Agency, facilitates

orchestrating, synchronizing, and integrating program management of contingency

acquisition support across combatant commands and USG agencies, during combat,

post-conflict, and contingency operations. Once the JCASO attains full operational

capability at the end of FY 2010, its deployable teams can augment a CCDR’s staff to

assist in providing oversight and program management at the operational-level over the

array of contracts and contractors throughout the AOR.

(2) The deployable teams are multifunctional with expertise in engineering,

logistics planning, contracting, and acquisition. The forward team will have reachback to

other JCASO team members at Fort Belvoir, VA, for legal, financial, and other support

capabilities; including a liaison to interagency partners to assist with the whole-of-

government approach to shaping and managing a contingency operation.

c. JOCSPs are assigned to the geographic combatant commands, USSOCOM and

USJFCOM. The JOCSPs assist CCDR and their staffs in identifying the requirements for

contractor services, as well as the performance standards. The requirements will

incorporate DOD and the CCDR’s policies and standards regarding contractor performance

and the provision of life support and other services for military personnel and contractor

personnel in forward areas. The JOCSPs work with operations, logistics, and contracting

planners to develop contracting support annexes and contractor management annexes.

SECTION B. OPERATIONAL INTEGRATION OF ARMED

PRIVATE SECURITY CONTRACTORS

8. General

a. The CSIP prepared for APSC support is designed to enable the supported GCC

and subordinate JFCs to properly synchronize and coordinate all the different contracting

III-9

Armed Private Security Contractor Planning, Integration, and Management

support actions planned for and executed in an operational area. While joint doctrine and

DOD guidance for the employment of contractors and specifically armed contractors

contains detailed guidance on the employment of contractors, in the absence of governing

federal law, the language of the contract rules. Commanders do not command contractors,

nor can they direct actions outside the work stipulated in the contract itself.

b. Factored into planning and integration for APSC support is the DOD-wide use of

SPOT. Combatant commands are continuing to transition from manual accounting of

contractor personnel to a this web-based, database tool to track contractor personnel

and contractor capability in theater. SPOT has a number of features that facilitate individual

contractor management. For example, USCENTCOM is using SPOT to generate Letters

of Authorization that are required for contractors receiving government furnished support

in the AOR. Additionally, SPOT allows for the scanning of identification cards to track

the movements of contractor personnel and equipment through key life-support and

movement nodes.

9. Armed Private Security Contractor Integration Initiatives

Developed by United States Central Command

a. The following organizations, systems, and mechanisms are initiatives that have