Vienna International Centre, P.O. Box 500, A-1400 Vienna, Austria

Tel: (+43 1) 26060-0, Fax: (+43 1) 26060-5866, www.unodc.org

Printed in Slovakia

SWEDEN’S SUCCESSFUL DRUG POLICY:

A REVIEW OF THE EVIDENCE

FEBRUARY 2007

cover_sweden2.qxd 2/14/2007 2:00 PM Page 1

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PREFACE........................................................................................................................................4

PREFACE........................................................................................................................................5

INTRODUCTION...........................................................................................................................7

PART 1: THE SWEDISH DRUG CONTROL POLICY ............................................................9

THE EMERGENCE OF DRUG ABUSE IN SWEDEN .....................................................................9

TOWARDS A NATIONAL DRUG CONTROL POLICY .................................................................9

The Narcotics Drug Committee................................................................................................9

The 1969 ten-point anti-drugs programme.............................................................................10

Drugs on prescription-the Stockholm experiment ..................................................................11

The role of Nils Bejerot in shaping Swedish drug control policy ...........................................12

The introduction of methadone maintenance therapy ............................................................13

Sweden’s role in the negotiations of the 1961 and 1971 United Nations drug control

conventions .............................................................................................................................13

SETTING THE VISION OF A DRUG-FREE SOCIETY.................................................................14

A progressively restrictive policy ...........................................................................................14

Changes in the treatment system ............................................................................................15

The introduction of needle exchange programmes.................................................................16

Drug use becomes a punishable offence.................................................................................16

REAFFIRMING THE VISION OF A DRUG-FREE SOCIETY ......................................................17

The 1998 Drugs Commission..................................................................................................17

The National Action Plan on Drugs .......................................................................................18

SWEDISH DRUG POLICY IN PERSPECTIVE ..............................................................................20

PART 2: THE DRUG SITUATION IN SWEDEN ....................................................................23

AMPHETAMINE - THE MAIN PROBLEM DRUG........................................................................23

Development of amphetamine use from 1940 to date.............................................................24

DRUG USE IN SWEDEN SINCE 1970............................................................................................26

The expansion of drug abuse in the 1990s..............................................................................27

Downward trend in drug abuse from 2001/02 to 2005/06 .....................................................31

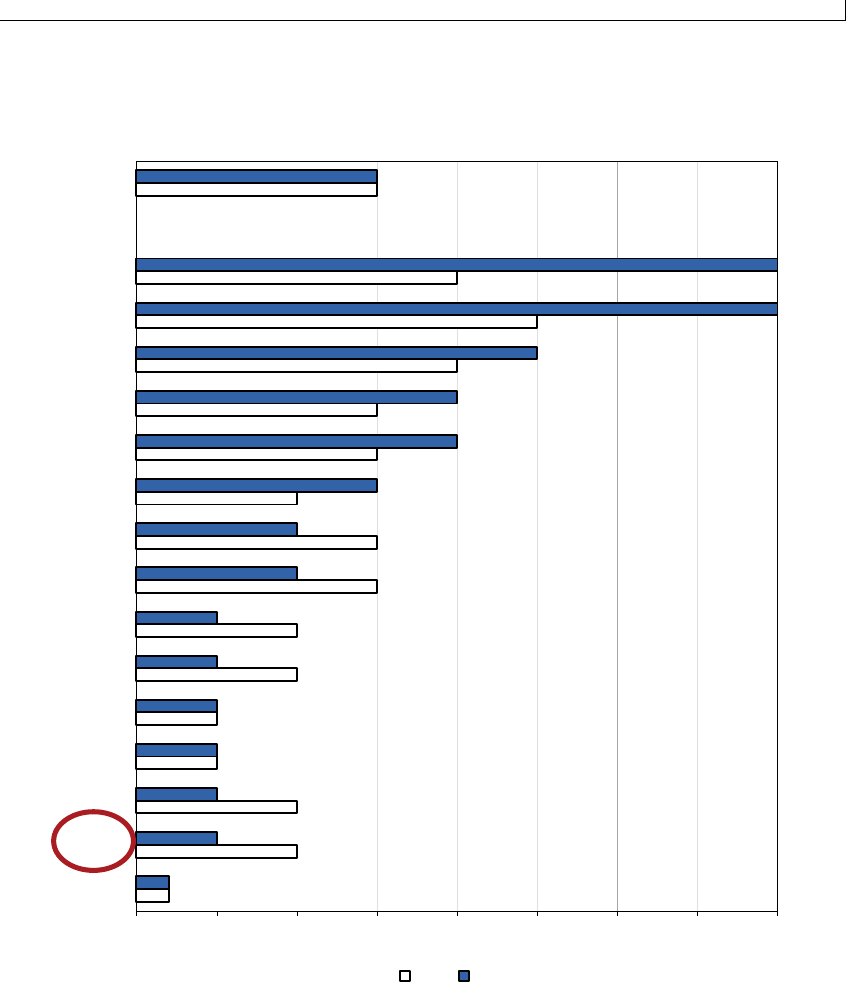

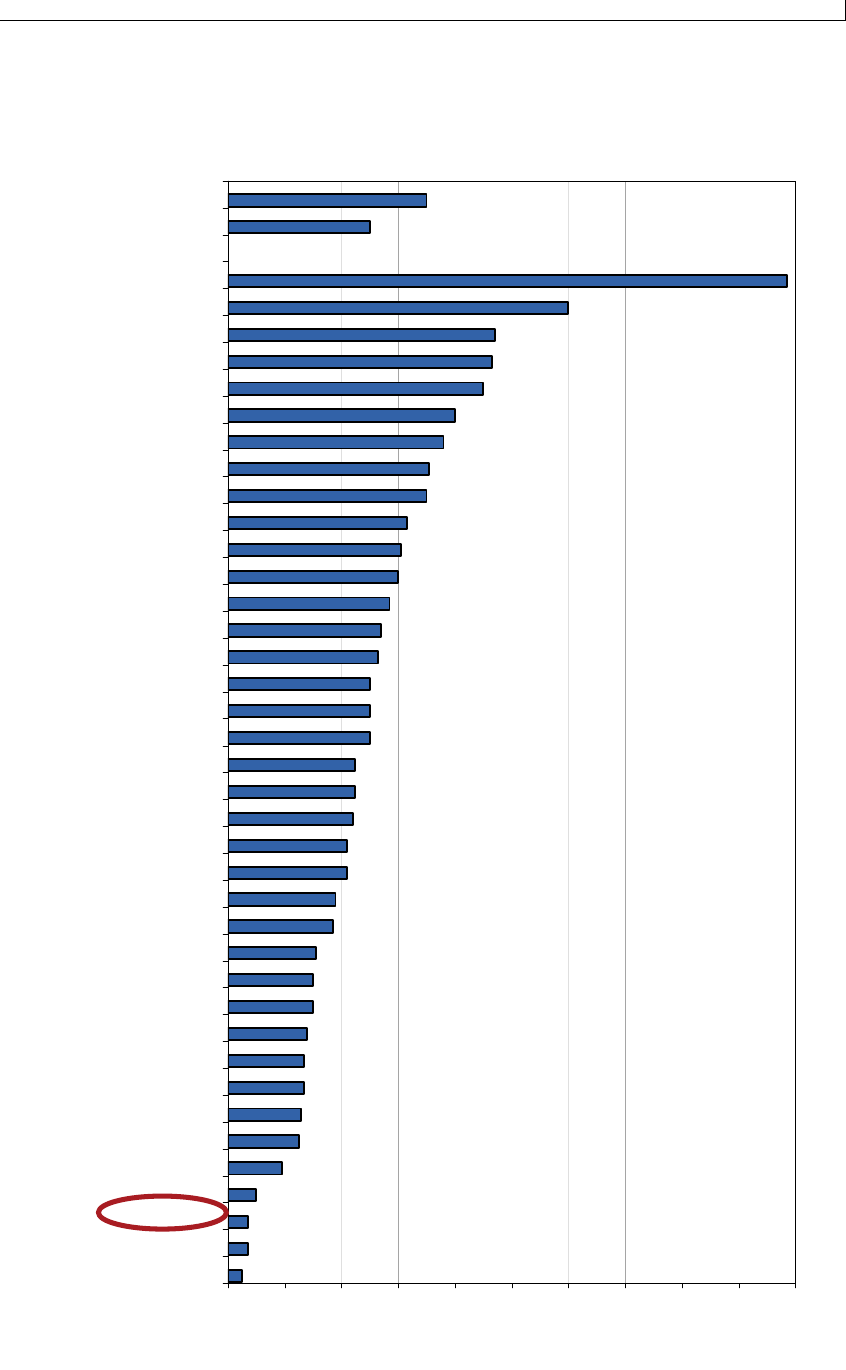

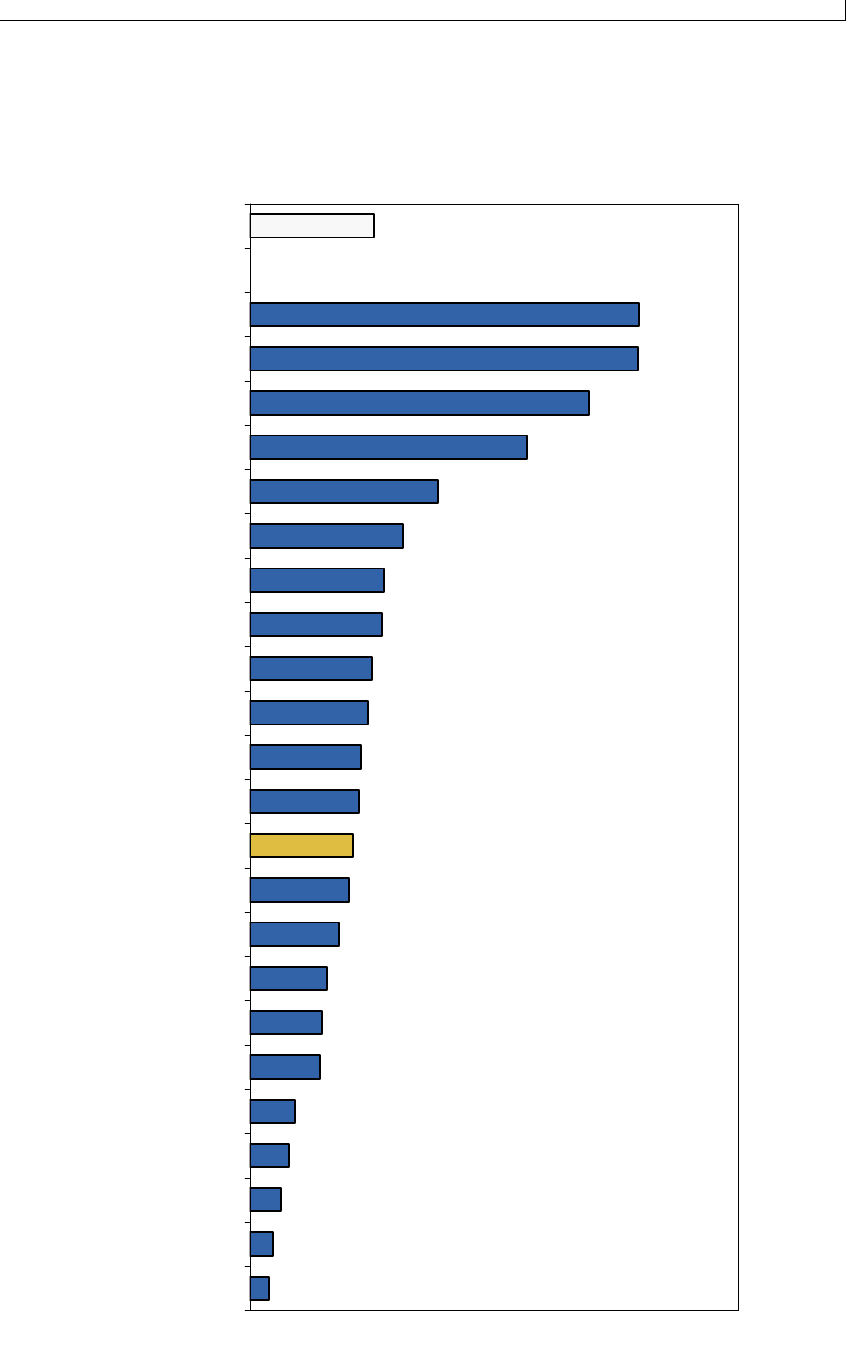

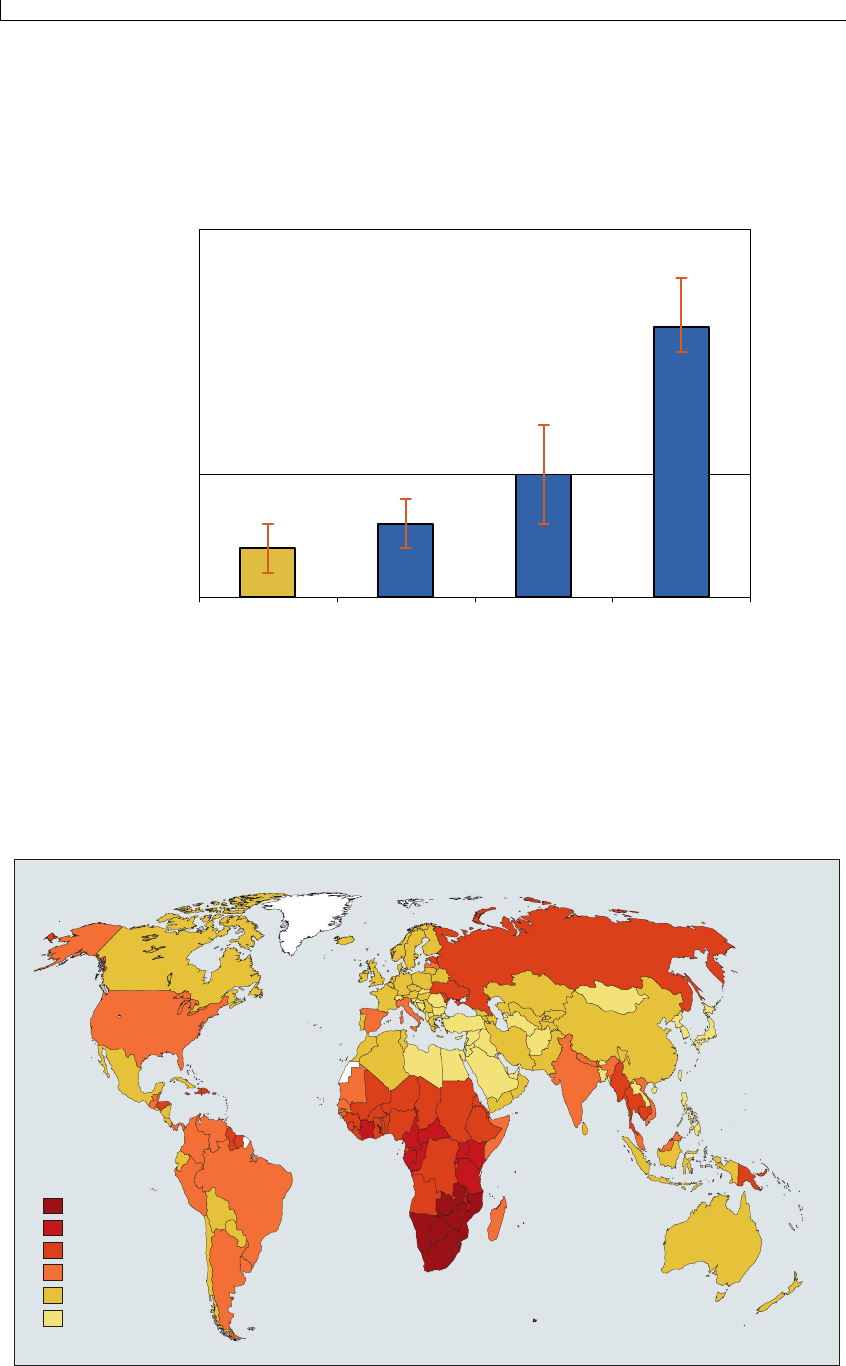

THE DRUG SITUATION IN SWEDEN - AN INTERNATIONAL COMPARISON .....................36

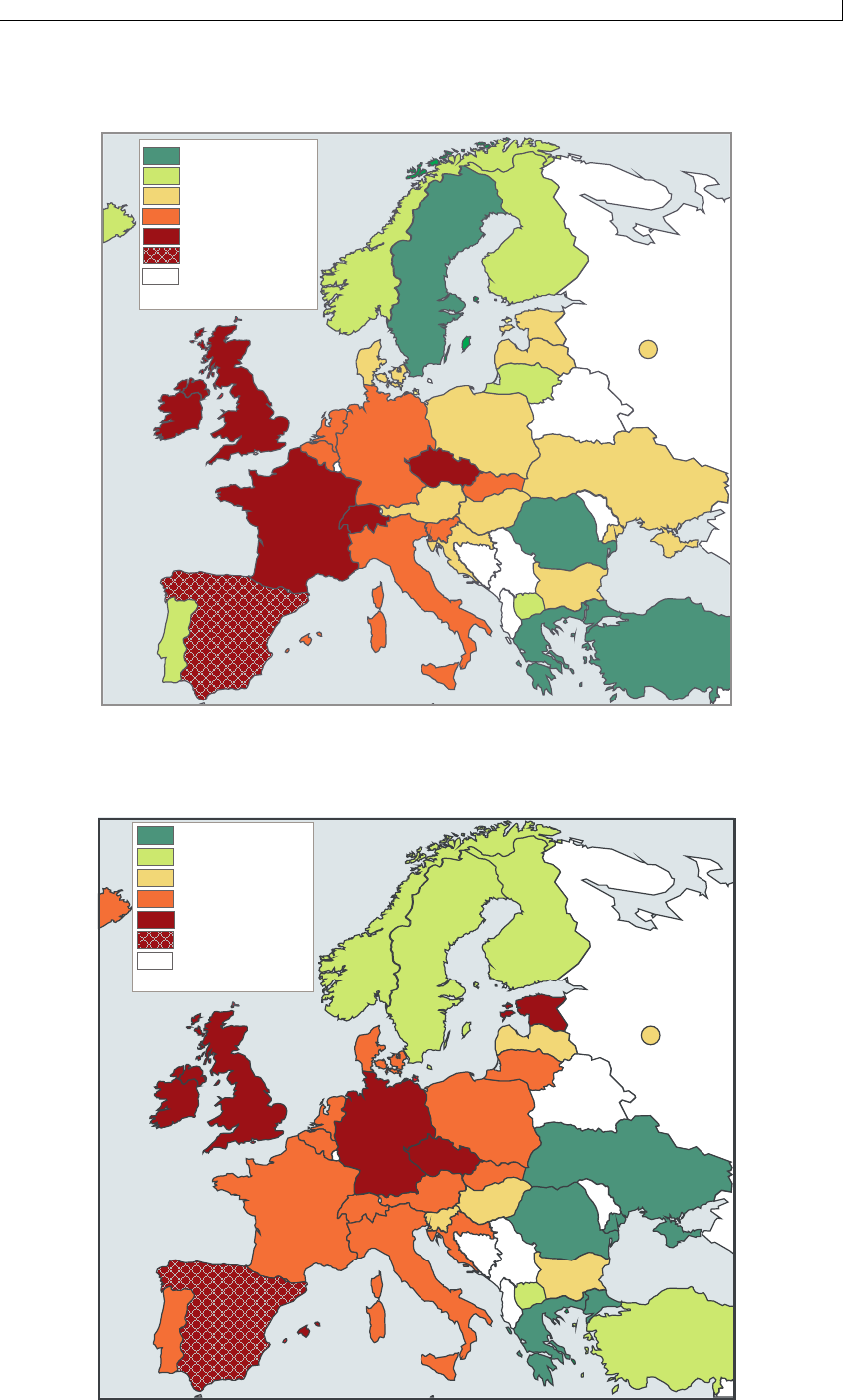

Life-time prevalence of drug use among students...................................................................36

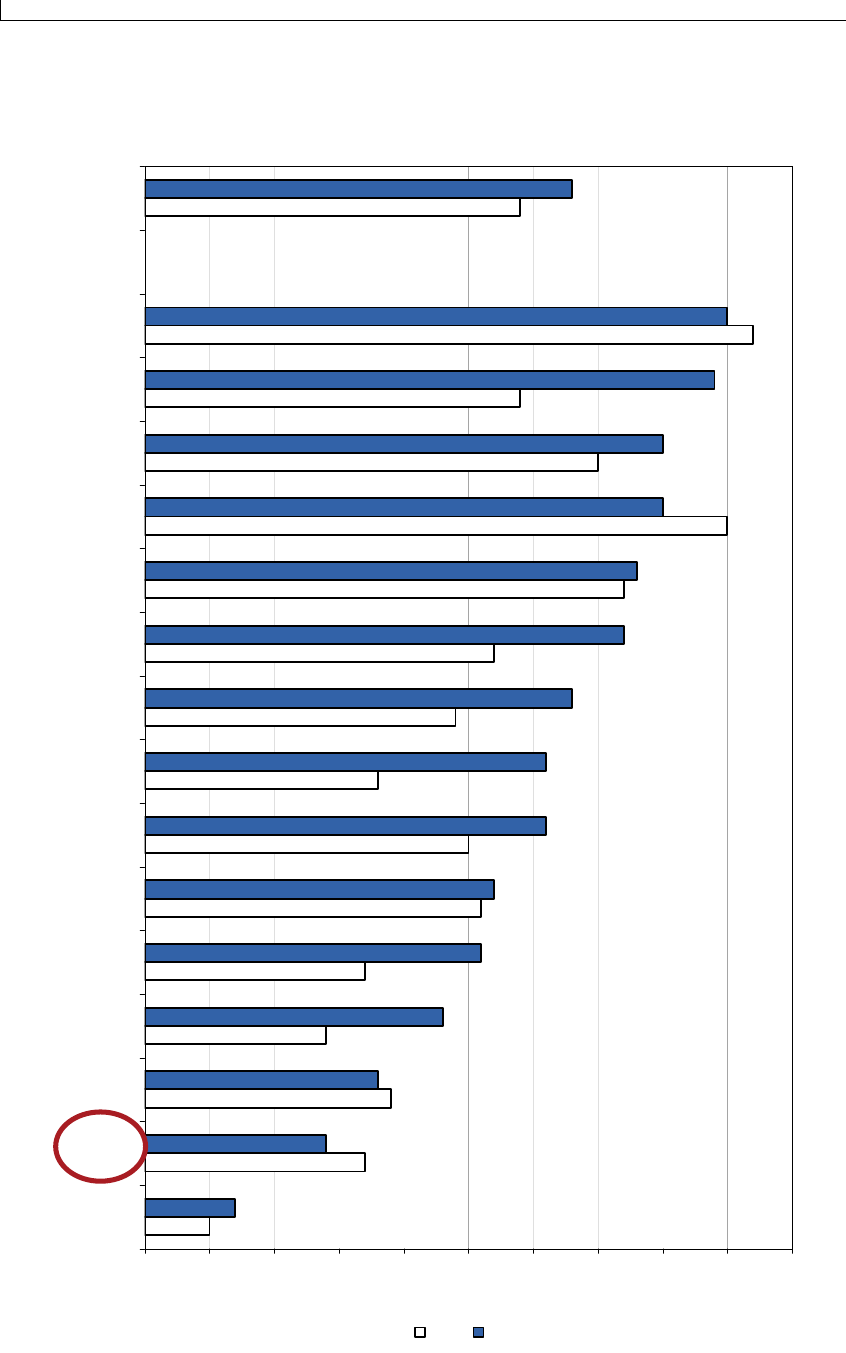

Regular drug use ....................................................................................................................38

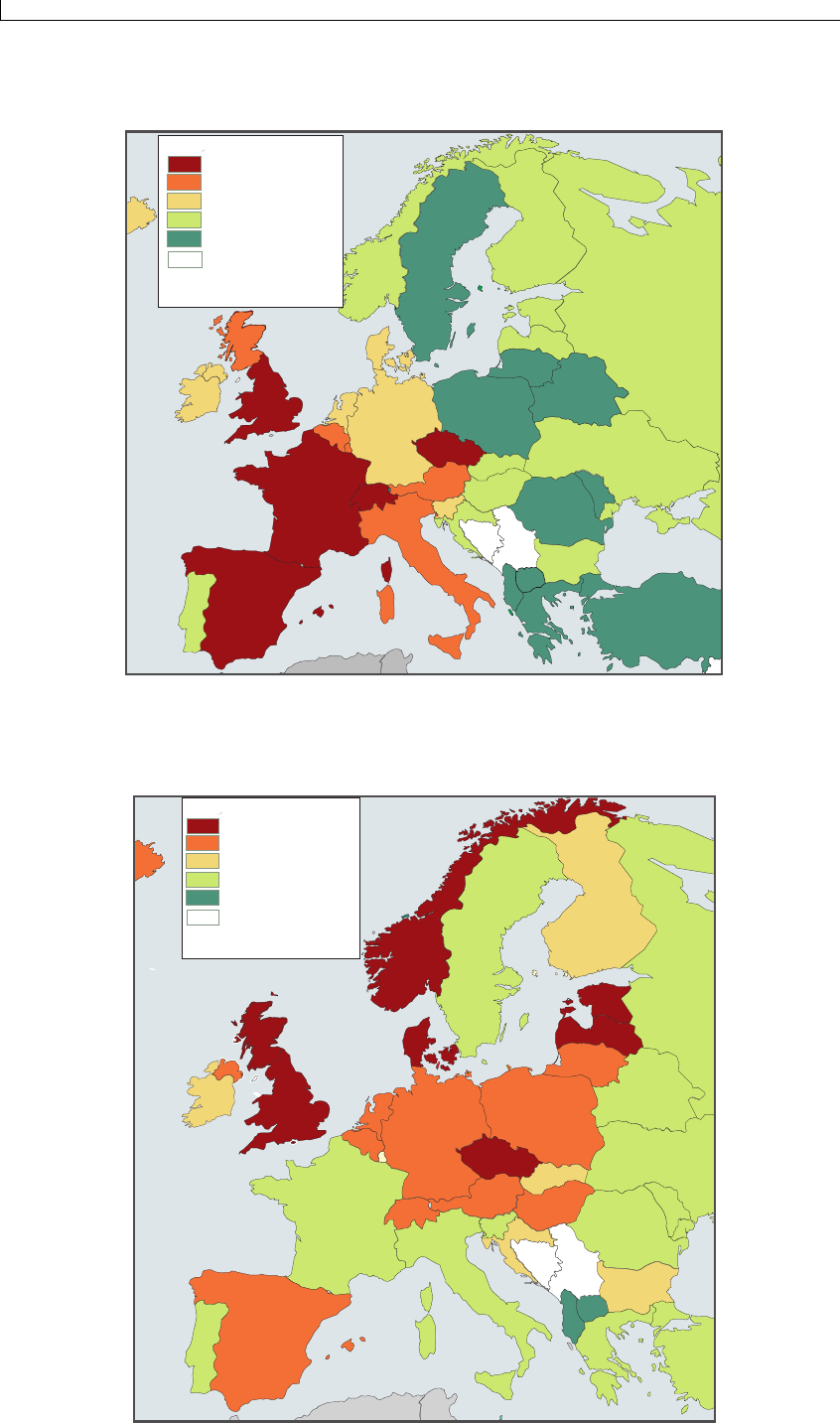

Perceived drug availability.....................................................................................................44

Perceived risk of drug use ......................................................................................................46

Experiences with visible drug scenes......................................................................................48

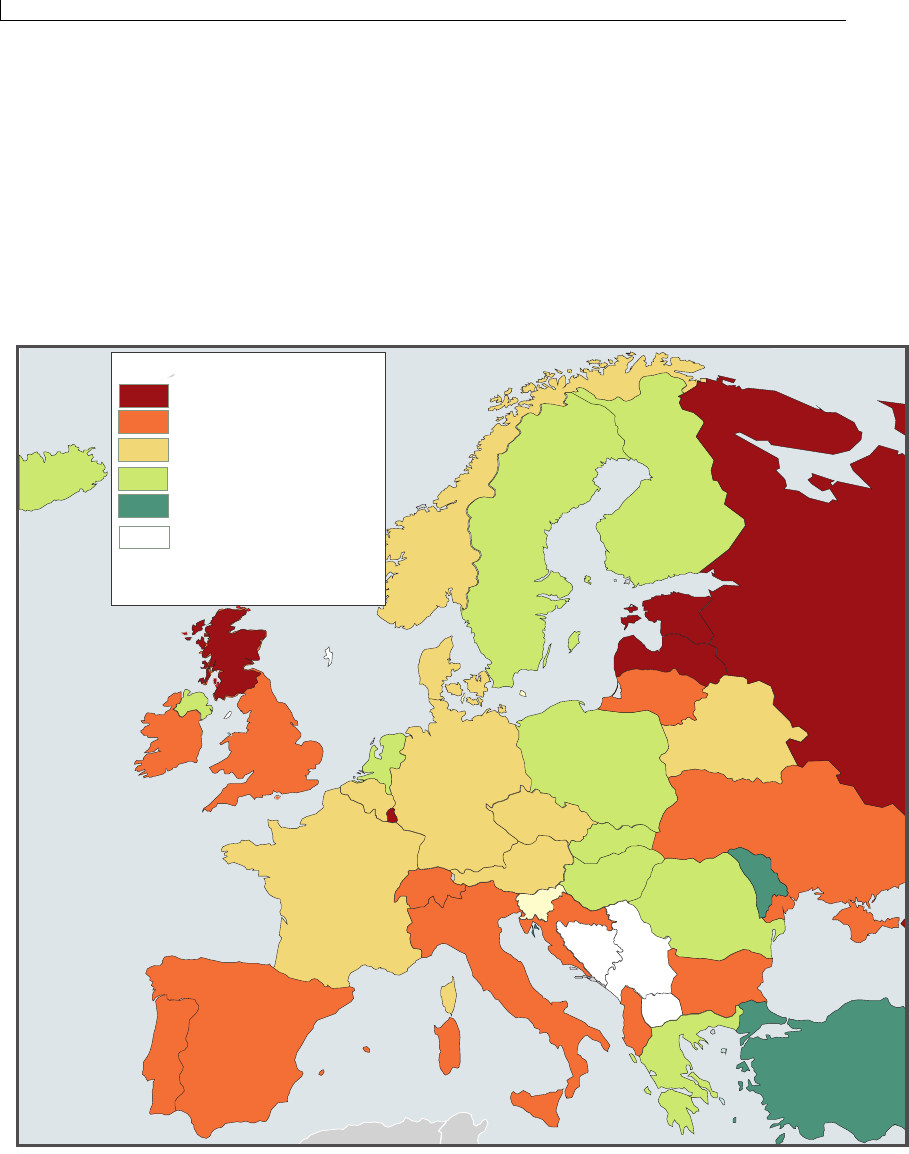

Problem drug use estimates....................................................................................................49

Intravenous drug use and HIV/AIDS......................................................................................50

CONCLUSION .............................................................................................................................51

STATISTICAL ANNEX...............................................................................................................53

LONG-TERM DRUG USE TRENDS IN SWEDEN ........................................................................53

INTERNATIONAL COMPARISONS..............................................................................................56

YOUTH SURVEYS..................................................................................................................56

Surveys among 15-16 year old students .................................................................................56

Surveys among 15-24 year olds..............................................................................................62

GENERAL POPULATION SURVEYS............................................................................................69

PERCEIVED RISK OF DRUG USE.................................................................................................78

OTHER DRUG ABUSE RELATED DATA.....................................................................................82

INTRAVENOUS DRUG ABUSE AND HIV/AIDS.........................................................................84

4

PREFACE

The supply and abuse of drugs effects every country all over the world in one way or another. The

Swedish vision is that drug abuse shall remain as a marginal phenomenon in the society. Solidarity

with disadvantaged and vulnerable members of society, not least, demand as such. People are

entitled to a life of dignity and a society which safeguards health, prosperity, security and safety of

the individual. The vision is that of a society free from narcotic drugs.

The overriding task of our drug policy is to prevent abuse. Preventive measures shall strengthen

the determination and ability of the individual to refrain from drugs.

Young peoples’ attitude towards drugs demands special attention. At the same time we must

emphasize the importance of an interaction between control measures, other preventive efforts and

treatment. This interaction is essential if the fight against narcotics is to be successful.

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime has decided to present a report on the Swedish drug

policy and its implementation. I am of course proud that the overall judgement is positive, even if

there also are critical remarks. We have far from solved the drug problem, perhaps we never will,

but the political commitment will remain very strong from both the Parliament and the

Government. I am convinced that the path we have chosen and the steps we have taken are in the

right direction even if there is much more to do.

As the report points out it is difficult to establish a direct and causal relationship between policy

measures and results. Our experience is that in times where we have thought that the problems

where more or less under control and the drug problem was given less priority, we could see an

increase in drug consumption among young persons. We learned that we have to convince every

generation.

I am convinced that it is possible to tackle the drug problem, but we need strong commitment from

society and support from the general public. We have today a political consensus and support from

the public for a comprehensive and restrictive drug policy, based on the UN conventions, which

include both supply- and demand reduction.

Maria Larsson

Minister for Elderly Care and Public Health

5

PREFACE

Drug use in Europe has been expanding over the past three decades. More people experiment with

drugs and more people become regular users, with all the problems this entails for already strained

national health systems. There are thus suggestions, at the European level, that drug policies have

failed to contain a widespread problem.

Sweden is a notable exception. Drug use levels among students are lower than in the early 1970s.

Life-time prevalence and regular drug use among students and among the general population are

considerably lower than in the rest of Europe. In addition, bucking the general trend in Europe,

drug abuse has actually declined in Sweden over the last five years. This is an achievement that

deserves recognition.

I am personally convinced that the key to the Swedish success is that the Government has taken

the drug problem seriously and has pursued policies adequate to address it. Both demand reduction

and supply reduction policies play an important role in Sweden. In addition, the Government

monitors the drug situation, examines the policy from time to time and makes adjustments where

they are needed.

Sweden, of course, has had some advantages in addressing the drug problem. Sweden is not

located along major drug trafficking routes. Income inequalities, which often go hand in hand with

criminal activities including drug trafficking, are low. Unemployment, including youth

unemployment, is below the European average. This reduces the risks of substance abuse.

International surveys show that the Swedish population is particularly health-conscious, so less

prone to large-scale drug use. There is a broad consensus that production, trafficking and abuse of

drugs must not be tolerated. Thus a clear and unequivocal message is given to the general public,

notably to the country’s youth. Last but not least, with its strong economy, Sweden has the

wherewithal to devote adequate resources to dealing with the drug problem. Increases in the drug

control budgets in recent years went hand in hand with lower levels of drug use.

It is my firm belief that the generally positive situation of Sweden is a result of the policy that has

been applied to address the problem. The achievements of Sweden are further proof that,

ultimately, each Government is responsible for the size of the drug problem in its country.

Societies often have the drug problem they deserve.

Antonio Maria Costa

Executive Director

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime

7

INTRODUCTION

The present report reviews the evolution of the drug control policy in Sweden, one of the most

widely examined and debated drug control policies in the world.

The Swedish drug control policy is guided by the vision and the ultimate goal of achieving a drug-

free society and the unequivocal rejection of drugs, their trafficking and abuse is considered

somewhat unique. This is particularly so when the drug policy in Sweden is compared to drug

control policies in other countries of the European Union. Over the years, the drug control policy

in Sweden has been subject to scrutiny numerous times, either at the national level, mostly by

expert Commissions established specifically for that purpose, or by scientific researchers both in

Sweden and internationally.

As part of its ongoing series on drug control policies at local and national level, UNODC has

decided to review the Swedish drug control policy that has evolved over the past forty years. It is a

rapid assessment, based on open-source documents, supplemented by Government documents and

information obtained from Government officials. While the report does not aim to be

comprehensive or exhaustive, an attempt has been made to thoroughly review the available

evidence, including data on drug abuse, dating back to the 1940s.

The document examines important junctures in Swedish drug control policy, including the often-

discussed Stockholm experiment of drug prescription, the introduction of methadone maintenance

programmes and, of course, the vision of a drug-free society. An analysis of the drug control

situation in Sweden over the years accompanies the document and shows how the drug control

situation has evolved over time.

It is difficult to establish a direct and causal relationship between specific policy measures and the

resulting drug situation. Nevertheless, in the case of Sweden, the clear association between a

restrictive drug policy and low levels of drug use is striking. Few people in Sweden are likely to

take drugs in their lifetime, and even less likely to use drugs regularly. Attitudes towards drugs

and their abuse is clearly negative. Preliminary calculations for the UNODC Illicit Drug Index, a

single measure of a country’s overall drug problem, show a very low value for Sweden which

indicates that its drug problem is small, compared to that of other States. However, the relatively

high proportion of heavy drug use among drug abusers remains a concern that has been difficult to

address. This document cannot provide definite answers to questions about how the levels of drug

abuse are influenced by policy measures. It can only present the facts and leave the readers to

draw their own conclusions.

Part 1: The Swedish Drug Control Policy

9

PART 1: THE SWEDISH DRUG CONTROL POLICY

The emergence of drug abuse in Sweden

Drug abuse was virtually unknown in Sweden until the 1930s. Excessive use of drugs was first

reported in 1933 but was a very limited phenomenon. An enquiry in 1940 to all state- and

municipally-engaged physicians gave a total of 70 known cases of drug abuse, mainly of opiates.

1

The introduction of amphetamines in about 1938, however, resulted in drug abuse becoming more

widespread. Soon, large sections of the Swedish population, were occasional or even regular users

of amphetamines. Countermeasures did not lead to a sustained reduction in use. The introduction

of prescription requirements for amphetamines, in 1939, for example, only brought about a short-

lived stabilization of sales. Soon after, sales skyrocketed as people found ways to circumvent

existing restrictions. In 1943, almost 10 million tablets of amphetamines were consumed annually

and the number of estimated users was 200,000 (4.6 per cent of the population age 15-64).

In 1943, the National Medical Board of Health of Sweden issued a warning on the risk and abuse

of stimulants. This measure resulted in a sharp drop in the sales of the substances. However, the

market recovered and abuse continued to spread. The introduction of new central-nervous system

stimulants of the amphetamine-type enlarged the market considerably.

Dexamphetamine and phenmetrazine were used as weight-reducing agent, while methylphenidate

was marketed as a lower-risk version of amphetamine. The increasing diversity in the number of

psychoactive substances on the market made the drug abuse problem more difficult to control.

In the first years of the emerging drug problem, authorities in Sweden usually took measures that

restricted the availability of a specific drug in question. This could be done by introducing

prescribing requirements for the drugs or, by further restricting prescribing practices. In addition,

the National Medical Board issued circulars which alerted the medical profession that these drugs

were particularly liable to abuse.

These policy measures usually had the desired effect. Immediately after their introduction, the

level of sales would decline. This was the case for amphetamines in 1943. Similarly, in 1962,

subsequent to a warning from the National Board on the dangers of certain groups of drugs and

restrictions for doctors to prescribe amphetamines, the number of prescriptions for these

substances declined significantly.

2

Towards a national drug control policy

The Narcotics Drug Committee

So far, the two main drug policy measures in Sweden were the introduction of prescription

requirements and the issuance of warnings on health-related consequences of the drugs in

question. As drug use further expanded in the 1960s, it became clear that these actions, limited to

a small number of specific drugs, were no longer sufficient to address the growing drug problem.

In response to a parliamentary question, the Minister of Social Affairs of Sweden announced in

May 1965, that an Expert Group on Narcotics Drug Abuse to review the problem would be set up

within the National Medical Board.

Two months later, on 1 July 1965, the group started its work. In January 1966, the group was

reorganized and enlarged to form a Narcotics Drug Committee, comprising five subcommittees,

on legislative aspects, on therapeutic approaches, on technical-diagnostic problems, on social

medical aspects and on methods of prevention.

The mandate of the Narcotics Drug Committee was wide-ranging and the Committee was

requested to study problems involved in the abuse of narcotic drugs from medical, legal and social

aspects, focusing on the following issues:

Sweden’s successful drug policy: A review of the evidence

10

(i) a fact-finding survey to give a picture of the strata of the population involved, the

number, age and characteristics of drug abusers, and their background, to define the

character of the abuse;

(ii) a study on treatment, survey existing methods of diagnosis and possible effects of the

individual and on society of the abuse on narcotic drugs;

(iii) to investigate the legislative angles;

(iv) to review methods of prevention from medical, legal and social points of view and to

elucidate possible causal relationships and their importance for the origin of drug

abuse and its spread in society.

The results of the Committee were published in 1967 and represent the first comprehensive study

on the drug problem in that country. The first report (SOU 1967:25), on drug abuse, showed the

results of surveys on the extent and patterns of drug abuse in various segments of the population,

discussed the forms of treatment of drug abuse and made recommendations, inter alia, to maintain

a central registry of drug abusers.

3

The second report (SOU 1967: 41) focused on the legal aspects of drug control. It also called for

systematic monitoring of prescriptions for some drugs, including central-nervous system

stimulants, narcotic drugs and depressants in order to follow the development of a problem and to

be able to detect sudden changes at an early stage.

4

The body of evidence obtained by the Committee was the basis for the adoption of legislation

dedicated to address the drug problem. The Narcotic Drugs Act (

Narkotikastrafflag (1968:64)) was

adopted in April 1968. The Act made the transfer, unlawful manufacture, acquisition and

possession of drugs a punishable offence and lays down penalties for drug-related crime.

The 1969 ten-point anti-drugs programme

In December 1968, a meeting of all the regional chiefs of police in Sweden was convened in

Stockholm and presided over by the National Police Commissioner. At the close of the meeting, it

was decided that the efforts of the Swedish police against illicit traffic in drugs

should be given

the highest priority

. The Swedish Government was notified of the decision and given information

regarding developments in illicit drug traffic.

5

Subsequently, in 1969, the Government of Sweden approved a ten-point programme for

increasing public efforts against the drug problem. It aimed at the following:

1. Strengthening the resources of the police and customs to cope with the drug problem;

2. Closer co-operation between the police and customs, both nationally and internationally;

3. The right of the police, subsequent to a court decree, to use wire-tapping to uncover those

who profit from the misuse of drugs by financing, smuggling and "pushing" or peddling,

on a grand scale;

4. Stiffening the maximum punishment from four to six years for serious narcotics

violations;

5. Improvement and co-ordination of social detection activities, emergency treatment and

after-care;

6. Rendering legislation regarding treatment more effective;

7. Summoning a conference of youth organizations in order to disseminate information

among young people concerning the dangers involved in using drugs;

8. Information to the public in general concerning the dangers of drug abuse;

9. Increased Swedish activity at the international level - above all, in the United Nations

Commission on Narcotic Drugs - in order to secure international legislation in the matter

of psychotropic substances, primarily amphetamine, phenmetrazine etc.,

Part 1: The Swedish Drug Control Policy

11

10. Creation of a joint committee with, among others, the heads of the National Police Board,

the Office of the Chief Public Prosecutor and Prosecutor of the Supreme Court, the

National Social Welfare Board, the National Board of Customs and the National Board of

Education.

6

In line with the prevailing view of the drug problem at the time, the ten-point programme is heavy

on law enforcement measures. Nevertheless, it also covers demand reduction issues, particularly

the provision of treatment services to drug abusers and the prevention of drug abuse.

Drug abuse prevention was one of the main tasks of the joint committee which was formed in

January 1969, pursuant to point 10 of the 10-point programme. One of the results was the

establishment of a demand reduction programme operated by youth organizations. In 1969, a

collection of facts about drugs ("Fakta om narkotika") was disseminated. At the same time, an

advertising campaign was conducted in the newspapers concerning the risks in the misuse of

drugs.

These demand reduction activities were accompanied by a further stiffening of penalties. As

foreseen in the programme, the maximum penalty for serious narcotics offences under the

Narcotic Drugs Act was increased from four to six years, and at the same time, the police were

allowed to wire-tap - subsequent to a court decision in each individual instance - in order to

uncover perpetrators of serious narcotics offences.

Sweden also stepped up its activities at the international level to bring about effective international

control of psychoactive substance. In January 1970, Sweden participated in the first special

session of the United Nations Commission on Narcotic Drugs in Geneva, and gave its firm support

to the Draft Protocol on Psychotropic Substances.

Drugs on prescription-the Stockholm experiment

In 1965, an experimental project was launched for the legal prescription of drugs, the idea being to

limit the harmful effects of drug use, both on society and individual abusers.”

7

The project was

launched by the National Medical Board and run by a small number of doctors. Both opiates and

amphetamines were prescribed for oral as well as intravenous use.

8

The project was not a scientific experiment, as it had no control group or a planned design. It was

based on a “liberal and non-authoritarian view” on drug prescription, which meant, that, although

patients were under medical supervision, they were in practice free to decide on their own

dosages. If they had finished with their prescriptions, they could easily request more drugs.

The number of patients participating in the scheme increased from about 10 in 1965 to more than

150 in 1967.

9

On average, 82 patients were being treated at any point in time. Altogether, some

3,300,000 dosages of amphetamines (about 15 kilograms) and 600,000 dosages of opiates (about

3.3 kilograms) were prescribed in the two-year period from April 1965 to May 1967.

10

It was

widely known that many patients supplied friends and acquaintances with considerable quantities

of narcotic drugs obtained on prescription.

11

Problems became apparent soon after the experiment had started. As the legally prescribed drugs

were increasingly diverted to the illicit market, the project drew criticism from the police and the

drug prosecutor.

12

In one case, preliminary investigations against three individuals suspected of

drug offences revealed information that one drug addict had used part of his prescription to inject

other drug abusers.

13

The proportion of arrested people showing signs of intravenous drug use

rose in Stockholm from 20 per cent in 1965 to 33 per cent in 1967.

14

By 1967 almost all doctors in the project had stopped prescribing drugs, with the exception of Dr.

Åhstrom, the doctor in charge of it. In February 1967, a report from the pharmaceutical bureau of

the National Board containing an account of the prescriptions in the project was sent to the

Disciplinary Committee of the National Medical Board. After investigation, the Disciplinary

Committee concluded that there was well-founded reason to assume that Dr. Åhstrom “had

misused his right to prescribe narcotic drugs. This is reason for withdrawing his right to prescribe

such drugs. However, because of the difficulty to provide adequate care for his patients, this shall

not take force immediately.”

15

For a transition period, a specially designated pharmacy had the

Sweden’s successful drug policy: A review of the evidence

12

right to dispense prescriptions for patients on a list provided by the National Medical Board. Dr.

Åhstrom was advised to refer his patients to psychiatric care at a hospital. It was estimated that the

ambulant prescription activities should be closed by 30 April 1967. Dr. Åhstrom appealed the

decision but the Government did not alter its decision.

The matter came to a head with, in April 1967, the overdose death of a 17-year old woman on

morphine and amphetamine which was shown to have been procured through the project received

wide media coverage. It is often assumed that the public outcry accompanying this tragic event led

to the closing down of the project. This is, however, not the case. The decision to stop the project

had been taken much earlier. The project finally closed down on 1 June 1967, obviously not

having achieved its intended goal.

As the curtailment of the project did coincide with the issuance of the reports of the Committee, a

link has sometimes been made between the curtailment of the project and the subsequent and

progressive restrictiveness of the Swedish drug control policy. However, a review of the

documents at the time does not support a clear association.

What is true, however, is that wide reporting on the experiment, particularly long after the

experiment had been terminated, continued. Over the years, it has come to symbolize a bygone era

of drug policy, embodying a more permissive attitude towards drug abuse. It has also been used

both as an illustration of how well-intended harm reduction measures can spin out of control and,

occasionally, even to show that the well-being of some participants in the project improved. As a

non-scientific experiment, it cannot serve as evidence for either argument.

A personal perspective of the “drugs on prescription” experiment

I was then working at the Solna Police Authority, which is now a part of the Stockholm County Police Authority.

We had three (!) known abusers in our area who lived in one-room apartments. They knew us, we knew them and

we used to visit them in their homes.

The situation changed dramatically soon after the trials started. There were sometimes 10-20 people, all under the

influence of drugs, and plenty of illegally prescribed drugs in these apartments, and there was nothing we could do

about it. A few months later there were hundreds of abusers in the area and the police had totally lost control of

them and the extent of drug abuse in the district. After a couple of deaths involving legally prescribed drugs, the

trials were suspended.

During the trial period, the number of drug offences dropped to almost zero, simply because personal use and

possession for personal use were not reported. However, there was a rise in nearly all other types of crime. The

police were basically unable to take action against street-level drug offences.

Source: Remarks by Detective Superintendent Eva Brännmark of the National Police Board of Sweden

at the International Policing Conference on Drug Issues in Ottawa, August 2003

The role of Nils Bejerot in shaping Swedish drug control policy

The theoretical foundation of Sweden’s restrictive drug policy of the 1970s and 1980s appears to

be largely based on the work of Nils Bejerot, who is sometimes referred to as the founding father

of Swedish drug control policy. A deputy social medical officer at the Child and Youth Welfare

Board of the City of Stockholm, Bejerot diagnosed first cases of juvenile intravenous drug use in

Stockholm in 1954, much earlier than in most other towns in Europe.

In 1965, Bejerot initiated a study at the Stockholm Remand Prison to monitor the spread of

intravenous drug abuse in Stockholm, which confirmed his scepticism of the consequences of

legally prescribing amphetamine to amphetamine users.

In 1969, Bejerot founded the ‘Association for a Drug-Free Society’ (RNS), which played an

important role in shaping Swedish drug policies.

16

He warned of the consequences of an

‘epidemic addiction’, prompted by young, psychologically and socially unstable persons who,

usually after direct personal initiation from another drug abuser, begin to use socially non-

accepted, intoxicating drugs to gain euphoria. He was particularly concerned with the highly

psycho-social contagiousness of drug use and considered contagion to be a function of

susceptibility of the individual and exposure to drugs.

Part 1: The Swedish Drug Control Policy

13

One key precondition for the spread was availability. While susceptibility of the individual was

difficult to influence, exposure could be limited through drug policy. Therefore, Bejerot concluded

that society had to have a restrictive drug policy to limit general exposure to illicit drugs. He also

argued that drug policy had to target the drug user, since the drug user was the irreplaceable

element in the drug chain while drug dealers could be easily replaced in the event of being

arrested. In addition, he saw the need for a broad popular support to be achieved through a broad

political agreement and massive information campaigns, leading to something like a popular

uprising against drug epidemics. The practical implications – which over the years were put into

practice – were: (i) to increase prevention and treatment activities as well as to criminalize not

only drug trafficking but also drug use, (ii) to target cannabis use as the first drug in the chain

towards drug abuse (based on the ‘gateway’/‘stepping stone’ hypotheses) and (iii) to create a

national consensus on drug policies across party lines, supported by civil society pressure groups.

The introduction of methadone maintenance therapy

As the prescription of amphetamines and opiates was failing in Stockholm, scientists in the nearby

town of Uppsala investigated new methods of treating heroin addicts. Reports on the clinical trial

with methadone maintenance, published in the Journal of the American Medical Association in

1965, created considerable interest in Sweden and the following year, in 1966, a Swedish National

Methadone maintenance programme was opened at the Psychiatric Research Center in Uppsala.

Sweden thus became the first country in Europe to carry out methadone maintenance treatment,

long before it became an established and accepted form of drug abuse treatment and despite the

fact, that the most “problematic” drugs in terms of treatment demand were amphetamines and not

opiates. The National Methadone Maintenance Programme operated in Sweden under the same

conditions for 23 years and was the longest-running in Europe. The programme was rather

extensive, in relation to the small population of heroin addicts, even in comparison to such

programmes in other countries known to be favourable towards harm reduction policies.

17

The

programme has generally been judged as being very successful. Among the positive results are: an

average yearly retention rate of 90 percent; a significant decrease in drug abuse, criminality and

prostitution compared with the situation before treatment and a dramatic reduction in mortality of

those staying in treatment.

18

Sweden’s role in the negotiations of the 1961 and 1971 United Nations drug

control conventions

At the international level, Sweden has always been an active participant in bringing about

international drug control. Already in the early 60s, it was party to most international drug control

treaties in force at the time, with the exception of the 1936 Convention for the Suppression of

Illicit Traffic in Drugs. Sweden had even become party to the controversial 1953 Opium Protocol,

which restricted opium production to only seven States in the world.

In 1961, Sweden was one of 73 States represented at the Plenipotentiary Conference for the

Adoption of the United Nations Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs and became a signatory to

the Convention. Sweden ratified the 1961 Convention in 1964.

Concerted international action against stimulants was a major concern for the Swedish

Government. Stimulants were not restricted in many countries in Europe where these substances

were manufactured, making all national efforts to curb their abuse difficult. Specialized traders

developed a brisk business supplying non-medical demand in countries with more restrictive

regulations, mostly in Scandinavia. Taking the lead in Scandinavia, Sweden urged manufacturing

States to cooperate.

19

In 1965, Sweden called on the World Health Organization’s drug

committees “to impose controls on stimulants and depressants.”

20

In 1970, Sweden participated in the first special session of the United Nations Commission on

Narcotic Drugs and assumed an active role in promoting the control of psychoactive substances.

During the negotiations for the Convention on Psychotropic Substances, Sweden, together with

other Scandinavian Governments and Soviet bloc countries, formed what drug policy researcher

McAllister called a “strict control” coalition that argued for stringent limitation of all classes of

Sweden’s successful drug policy: A review of the evidence

14

psychotropic substances.”

21

The provisions of the Convention that was eventually adopted in

1971, were in some respects weaker than what Sweden had hoped for, mainly due to the efforts of

the pharmaceutical industry which enlisted the help of former United Nations officials to ensure

that their products escaped control. The Convention did, however, succeed in placing stringent

controls over amphetamines, which continued to be Sweden’s prime concern in terms of abuse.

Sweden was not only advocating additional control measures at the international level. On the

contrary, in the run-up to the adoption of the 1972 Protocol amending the 1961 Convention, it was

Sweden that proposed a weakening of the penal provisions of the 1961 Convention, suggesting

that measures of treatment, rehabilitation and social integration should be offered to drug abusers

as an alternative to conviction or punishment or in addition to punishment.”

22

Sweden also proposed that the amended Convention should have a separate article requiring

parties to take all practicable measures for the prevention

of abuse of drugs and for the early

identification, treatment, education, after-care, rehabilitation and social reintegration of the

persons involved.

In introducing the amendments, the representative of Sweden stated that

“meaningful action against drug abuse must be directed both against supply and demand. There

must, in other words, be a proper balance between control measures, law enforcement etc. on the

one hand, and therapeutic and rehabilitative activity on the other. ”

23

Both amendments were

accepted and became articles of the 1961 Convention, as amended by the 1972 Protocol.

Setting the vision of a drug-free society

A progressively restrictive policy

At the national level, the 70s saw an increase in heroin abuse, resulting, as in other European

countries, in a higher mortality among drug abusers.

24

The Narcotics Drugs Act was amended

again, in 1972, with the maximum penalties for serious offences raised to 10 years. At the same

time, however, drug abusers were protected from prosecution. From 1972 onwards, prosecutors

could waive charges for possession of amounts equalling up to one week’s use.

Nevertheless, drug abuse continued unabatedly which, possibly, led to changed attitudes within

society. Very soon, some thought society had a duty to intervene against individual abusers whose

lives were in acute danger and to take more vigorous action against all forms of drug trafficking.

25

A parliamentary bill was therefore introduced in 1978 (Prop. 1977/78:105) which proposed to

raise the standards for drug control policy efforts. The standard should be to eliminate drug abuse

not simply lower it. The bill stated that: “The struggle against drug abuse may not be limited only

to reducing its existence but must aim at eliminating drug abuse. Drug abuse can never be

accepted as a part of our culture.”

26

The bill was approved by Parliament and endorsed the guiding

principles of the drug policy: “The basis for the struggle must be that society cannot accept any

other use of narcotic drugs than what is medically motivated. All other use is abuse and must

forcefully be opposed.”

27

Thereafter, policy was further tightened. In 1980, new directives to prosecutors ruled out any

waiver of charges unless the amount possessed for personal use was so small that it could not be

subdivided, that is, at most one dose of cannabis or one dose of central nervous system stimulants.

Moreover, charges for possession of heroin, morphine, opium or cocaine, should, in principle,

never be waived at all. One year later, the penalties for drug offences were raised again; the

maximum prison terms for non-serious offences were raised from 2 to 3 years; in addition

minimum sentences for serious offences were raised from one to 2 years. In 1982, the Social

Services Act was amended and permitted the State to coerce adult drug abusers into treatment.

October 1984 saw the adoption of another Government bill (Prop. 1984/85:19) on a “coordinated

and intensified drug policy”, which spelled out the aim of Swedish drug policy as a drug-free

society: “The goal of society’s efforts is to create a drug-free society. This goal has been

established by Parliament and has strong support among citizens’ organizations, political parties,

youth organizations and other popular movements.”

28

The bill encouraged people to play an

Part 1: The Swedish Drug Control Policy

15

active role, stating that “everybody who comes in contact with the problem must be engaged, the

authorities can never relieve [individuals] from personal responsibility and participation. Efforts

by parents, family, friends are especially important. Also schools and non-governmental

organizations are important instruments in the struggle against drugs.”

29

This vision of a drug-free society still remains the overriding vision. The ultimate aim is a society

in which drug abuse remains socially unacceptable and drug abuse remains a marginal

phenomenon. In this visionary aim, drug-free treatment is the preferred measure in case of

addiction and prosecution and criminal sanctions are the usual outcome for drug-related crime.

30

Changes in the treatment system

Following the proclamation of a drug-free society, the focus was increasingly on the abuser. Drug

abusers could be coerced into treatment. The Social Services Act (1980:620) made it possible to

commit adult abusers of alcohol or drugs within the social services to coercive care.

A compulsory care order in Sweden can only be issued if certain legal conditions are met. The two

conditions are: (a) that the person is in need of care/treatment as a result of ongoing abuse of

alcohol, narcotics and volatile solvents and that (b) the necessary care cannot be provided under

the Social Services Act. The first option for the substance abuser is always voluntary treatment

under the Social Services Act. The social welfare committee, which works on the prevention and

countermeasures of abuse of alcohol and other addictive substances, acts in consensus with the

individual, according to Section 11 of the Act. The modalities of coercive care were laid down in

the Care of Abusers (Special Provisions) Act (1981:243), which entered into force in 1982, at the

same time as the Social Services Act. The introduction of compulsory treatment brought about an

increase in the number of patients treated.

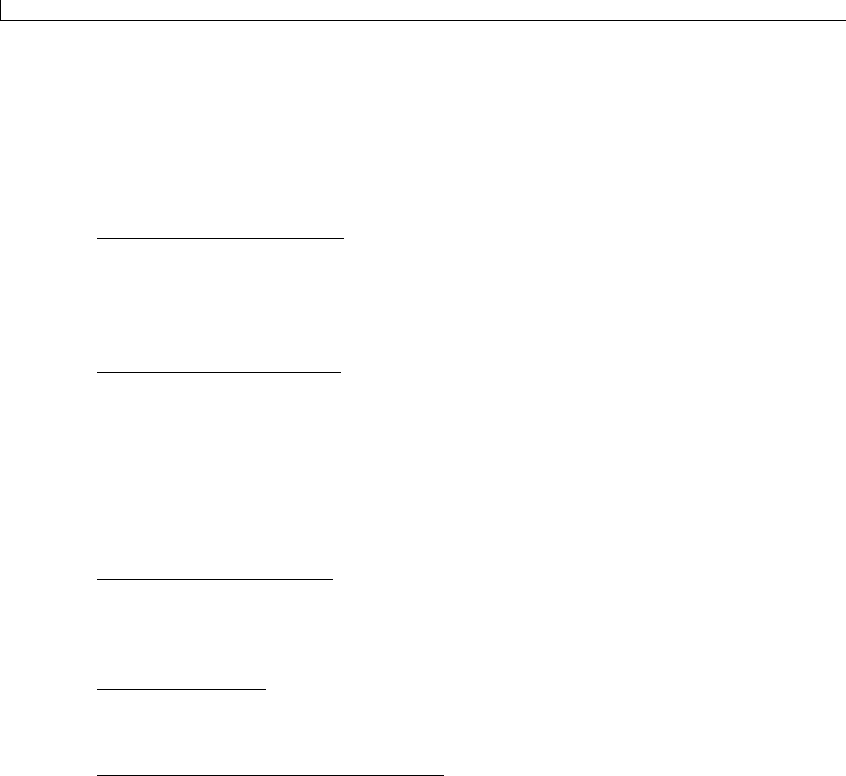

Figure 1: Number of patients discharged after compulsory treatment in Sweden, 1982-1988

0

50

100

150

200

250

1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988

Number of patients

Source: Adapted from Mats Ramstedt, The drug problem in Sweden in 1979-1997 according to official statistics, in Håkan

Leifman and Nina Edgren Henrichson (eds), Statistics on alcohol, drugs and crime in the Baltic Sea region, Nordic Council for

Alcohol and Drug Research, Publication Nr. 37, Helsinki, 2000

Conditions for coercive care were modified in 1988. The maximum coercive care period was

extended from two to six months and the target group was extended to include abusers of solvents.

The Care of Alcoholics, Drug Abusers and Volatile (Special Provisions) Act (1988:870) aims to

motivate drug abusers so as to induce them to “collaborate in continued treatment and accept

support to discontinue” abuse.

31

The conditions that have to be met include not only “running an

obvious risk of destroying his life”

32

but also when “it can be feared that he will inflict serious

damage on himself or on someone with whom he has a close relationship.”

33

The concept of compulsory care may be seen as a logical consequence of the pursuit of the

objective of a drug free society. But it is not unique to Sweden. It has also been applied in a

number of other countries, including in countries such as the Netherlands

34

which have a different

vision.

Sweden’s successful drug policy: A review of the evidence

16

In the 1990s, the number of patients admitted to residential care, both voluntary and coercive,

decreased, mainly due to budgetary constraints in the early years of the decade. Subsequently,

priority was given to persons who were willing to undergo treatment. Thus, as of 1 November

2005, only 6 per cent of all substance abusers in residential treatment within the social services

system were in coercive care.

Other factors may have also played a role. With the advent of HIV in Sweden, the concept of

“Offensive Drug Abuser Care” was developed which emphasizes outreach activities and aims at

motivating drug abusers for treatment. As of 1986, so-called drug abuser care bases were

established in the main municipalities and in the social welfare districts of the larger cities. A

number of new residential treatment centres were opened and numerous joint projects were started

by social services and prison and probation authorities. Budgetary constraints in the early 1990s

led, however, to a reduction in some of these activities. As the budget situation improved in recent

years, the main trend has been to develop open care options

.

The introduction of needle exchange programmes

In 1985, the number of newly registered HIV positive persons among injecting drug users was 142

(45 per cent of all reported cases) and in the following year, when 204 additional cases of HIV

infection were recorded, a debate flared up. Should drug-free treatment continue to be the main

policy of treating drug abusers or should the policy instead be aimed at limiting the social and

medical damages? It was decided that both were possible. The strict line was maintained while

harm reduction measures were implemented in areas where they were needed.

Needle exchange programmes started, on a project basis, in Malmö and Lund in 1987 and 1986

respectively. In Malmö, some 1000 people are involved in the programme annually.

35

Along with

the Netherlands, Sweden was one of the first countries in Europe to introduce these programmes.

In April 2006 the Swedish Parliament endorsed a Government Bill proposing a new law (Lag

(2006:323) allowing needle exchange programmes across the country on certain conditions. The

National Board of Health and Welfare may issue a permit to a regional health authority to run

needle exchange programmes provided that the application has been endorsed by the local

community. The programmes should be organised to motivate drug abusers to seek treatment and

the applicant health authority must describe how it is going to meet the needs for detoxification

and treatment. The new law took effect on 1 July 2006.

Drug use becomes a punishable offence

Drug abuse became a punishable offence in 1988. At the time, it was argued that this was

necessary “in order to signal a powerful repudiation by the community of all dealings with

drugs.”

36

In addition, it was felt that criminalizing personal consumption would have a preventive

effect, particularly among youths. Further emphasis was placed on the importance of adopting a

uniform approach within the Nordic countries- drug use was already an offence in Norwegian and

Finnish legislation. The most severe punishment was a fine.

In 1993, the law was further tightened by introducing imprisonment into the scale of punishments

(1992/93:142). Police were now empowered to undertake a bodily examination in the form of

urine or blood specimen test where there are reasonable grounds to suspect drug use. The purpose

of the more severe provision was to “provide opportunities to intervene at an early stage so as to

vigorously prevent young persons from becoming fixed in drug misuse and improve the treatment

of those misusers who were serving a sentence.”

37

However, in an evaluation of the criminal

justice system measures, the National Council for Crime Prevention of Sweden concluded that

“based on available information on trends in drug misuse there are no clear indications that

criminalization and an increased severity of punishment has had a deterrent effect on the drug

habits of young people or that new recruitment to drug misuse has been halted.”

38

On the contrary,

the Council found that drug experimentation among young people, increased throughout the

1990s, a trend, which was similar in Sweden to that in other countries.

Swedish drug control policy also changed by introducing stricter legislation for drug-related

offences:

Part 1: The Swedish Drug Control Policy

17

Progressive tightening of Swedish drug laws (1968-1993)

1968 Narcotics Drugs Act (Narkotikastrafflag (1968:64) adopted

1969 Maximum sentence for serious offences raised to 4 years imprisonment

1969 Maximum sentence for serious offences raised to 6 years imprisonment

1972 Maximum sentence for serious offences raised to 10 years imprisonment

1980 Circular of Prosecutor-General on certain questions regarding the handling of narcotics

cases: dropping of prosecutions for drug offences should be limited to cases involving

only possession of indivisible amounts of drugs

1981 Maximum sentence for non-serious offences raised to 3 years imprisonment

1981 Minimum sentence for serious offences raised from 1 to 2 years imprisonment

1981 Introduction of coercive care for drug abusers

1985 Prison term for minor drug offences raised to maximum of 6 months

1988 Drug use becomes punishable offence, punishable with fine

1988 Act on Treatment of Alcoholics and Drugs Misusers (1988:870)

1993 Drug use becomes imprisonment offence (1992/93:142)

Reaffirming the vision of a drug-free society

The 1998 Drugs Commission

During the economic crisis of the 90s, major cuts were made at the local level. Municipalities

were not allowed to raise taxes and this meant that resources were directed towards care of the

elderly and the disabled. Resources for social services were kept at more or less constant level but

were directed to areas other than the care and treatment of drug abusers. According to the National

Board of Health and Welfare, the costs of addiction care expressed as a proportion of social

services cost decreased gradually from 1995. Heavy drug abusers suffered most from the funding

cuts. Outreach work for drug abusers became a rarity. The funding cuts coincided with an

increase of drug abuse and drug-related problems.

The renewed drug problems resulted in the appointment of a Special Commission - the Drugs

Commission - in 1998. The six-expert Commission had the mandate to revise, discuss and propose

all possible options to improve governmental action toward the goal of a society free of drugs.

The report of the Commission was issued in 2001, ominously entitled “Crossroads - the drug

policy challenge.”

The Commission identified major deficiencies in the field of drug control and found that “the

present state of drug policy is above all due to a demotion of the drug issue as a political

priority.”

39

The absence of political concern, the Commission continued, is reflected in “reduced

funding of the public authorities and other sectors of the community which have to deal with

narcotic drugs and their consequences. During recent years, all sectors of society in this field have

experienced heavy cutbacks, simultaneously with the problem itself becoming severer and more

widespread.”

40

However, the overall goal of aiming for a society free from drug abuse was not put in question. On

the contrary, pronouncing itself on the general direction of the policy, the Drugs Commission

stated that “Sweden’s restrictive policy on drugs must be sustained and reinforced. The

Commission finds no arguments or facts to suggest that a policy of lowering society’s guard

against drug abuse and drug trafficking would do anything to improve matters for individual

abusers or for society as a whole.”

41

Sweden’s successful drug policy: A review of the evidence

18

This is not to say that the Commission did not find fault with the national drug policy at all. The

Commission was most critical of activities, or the lack of sustained activities, taken to reduce the

demand for illicit drugs. In its report, the Drug Commission put forward suggestions aimed at

creating coherence and balance and at strengthening, renewing and developing the restrictive

policy on drugs. Some of the main findings of the Commission concerned:

• Stronger political leadership:

The Commission noted a need for stronger prioritization,

clearer control and better follow-up of drug policy and recommended the appointment

of a minister specifically charged with the direction of drug control activities. The

Government responded by creating the post of a National Coordinator on Drugs who

took office in January 2002.

• Measures to combat demand

: The Commission noted that much of the preventive work

that was done was characterized by temporary measures and projects which are often

incapable of impacting on regular activities. The Commission also found grave

deficiencies in the design of drug abuser care, added to which, the volume of such care

is not commensurate with actual needs. Focusing on prevention, the Commission noted,

that for preventive measures to succeed, they must be “included in a system of measures

restricting availability, and there must be clear rules which include society’s norms and

values, as well as effective care and treatment.

• Measures to combat supply

: The Commission did not find any real deficiencies in the

legislation or the working methods used by the authorities in the control sector.

Cooperation between the authorities worked. Nevertheless, it called for further resources

with a view to reducing the supply of drugs.

• “Criminal welfare”:

The Commission saw an urgent need for resources to be allocated

to the prison and probation system, particularly for the intensification of its measures to

combat drug abuse.

• Competence development and research:

The Commission called for improvement of

knowledge of the drug situation, of laws and control measures, of methods relating to

prevention and treatment and of the effects of preventive measures and measures of

treatment.

The National Action Plan on Drugs

The findings of the Drugs Commission were the basis for the formulation of the National Action

Plan on Drugs that the Government adopted in January 2002. The National Action Plan on Drugs

(2002-2005) set out three main objectives: (1) to reduce the number of persons who engage in

illicit drug use, (2) to encourage more drug abusers to give up the habit and (3) to reduce the

supply of drugs.

In order to implement the vision of a drug free society, it was deemed necessary that

• more people are to become involved in the work;

• more people are to say ‘no’ to drugs;

• more people are to know about the medical and consequences of drugs;

• fewer people should start using drugs (to be achieved by reducing the desire of young

people to experiment with drugs and by breaking up environments and cultures that

attract and stimulate trying drugs for the first time);

• more abusers are to obtain help to a life free of criminality;

• the availability of drugs is to be reduced.

Activity areas, foreseen in the Action Plan, include, inter alia, new school-based programs;

interventions aimed at vulnerable groups; appropriate assistance for drug addicts; 10 million Euros

for prison and probation service; and information campaigns.

Part 1: The Swedish Drug Control Policy

19

The Action Plan foresees, however, a stronger goal orientation, with better coordinated measures

at the local, regional and national level to limit both supply and demand. For this purpose, a

National Drug Policy Coordinator was appointed by the Government with the task to implement

and follow up the National Action Plan. The main duties have been

• to develop cooperation with authorities, municipal and county councils, NGOs, etc.;

• to shape public opinion;

• to undertake a supporting function for municipal and county councils in the

development of local strategies;

• to initiate the development of methods, development and research;

• to serve as the Government spokesperson on drugs issues;

• to evaluate the action plan; and

• to report regularly to the Government (at least once a year).

The plan also spelled out that intensified measures were needed to make drug issues a strong

political priority, to improve cooperation among authorities and between authorities and private

sector organizations, to improve prevention and treatment through method & competence

development and research, to develop the treatment perspective within the correctional system, to

render the measures in the control area more effective, to improve the methods to monitor the

development in the drugs area as well as society’s responses, and to increase international

cooperation.

A total of SEK 325 million (about US$ 44 million) was allocated over a period of four years to

implement the plan. In actual fact, some SEK 405 million were invested in the implementation of

the plan (more than US$50 million or more than €40 million at 2006 exchange rates). A large

portion was spent on supporting research in order to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of

measures taken. The budget signaled additional resources, since the Drug Policy Coordinator did

not take over the responsibilities of other national authorities or authorities at the regional or local

level.

The Government provided additional resources for the development of local prevention policies

by providing earmarked grants that could be used for the development of prevention activities at

the local level, including the hiring of local coordinators of substance abuse prevention on a 50:50

per cent funding basis. As a consequence, a majority of all municipalities in Sweden has such

coordinators now. Coordinators work on substance abuse issues (alcohol and drugs), based on

Sweden’s public health model of integrated community based prevention activities.

The National Drug Policy Coordinator’s Office has been operating as a catalyst and agent for

mobilizing society at all levels towards a common goal: reducing drug use to come closer to the

ultimate vision of a drug-free society. By doing this, the National Drug Coordinator serves another

purpose: giving a human face to some abstract policies. This had been missing in Sweden’s drug

policy up to that time: a national anti-drug advocate and coordinator, who was responsible for the

implementation of the drug policies.

The implementation of most policies is aided if championed by an individual who exercises

leadership in his or her area of competence. While in the 1970s and 1980s this role was taken by

people such as the late Nils Bejerot who succeeded in mobilizing broad sections of the population,

a vacuum had been created in the 1990s. It has now been filled in a – seen from an institutional

perspective – far more rational manner than before.

The Office of the Drug Policy Coordinator has been successful in raising awareness of the drug

issue and a greater interest across society. It has also served as a signal to the local levels to take

the drug issue seriously.

The current policy model was successful and has therefore been maintained. The new Swedish

Anti-Drug Strategy (2004-2007) is in line with the restrictive drug policy. This involves no

Sweden’s successful drug policy: A review of the evidence

20

tolerance to drug abuse. Drug-related crime should always lead to prosecution and criminal

sanctions, and drug-free treatment is seen as a priority measure in response to addiction.

A new National Action Plan on Drugs was unanimously endorsed by Parliament in April 2006.

All parties agreed that the overall goal of the Swedish drug policy remains to strive for a drug-free

society. Parliament also underlined the importance of a holistic view. Drug policy initiatives

should target both supply and demand. There is a wide consensus about the overall goal of the

drug policy, namely the drug-free society and its objectives: to reduce the recruitment of young

people to drug abuse; to enable drug abusers to stop their drug abuse, and to reduce the availability

of illicit drugs. There is also consensus that a balanced approach is required.

42

The goal is outlined as follows: The drug policy is based on the right to a life with dignity in a

society that guards the needs of the individual to feel safe and secure. Narcotic drugs should never

be allowed to threaten the health, the quality of life and the security of the individual nor the

general welfare or the development of democracy. The goal is a society free of drugs.”

43

Swedish drug policy in perspective

The Swedish policy is fully in line with the three United Nations Conventions on drugs: the 1961

Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs, the 1971 Convention on Psychotropic Substances and the

1988 United Nations Convention Against Illicit Traffic in Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic

Substances. The International Narcotics Control Board, the independent, quasi-judicial expert

body responsible for monitoring the implementation of treaties by Governments, carried out a

mission to Sweden in 2004 and commended the Government for its commitment and efforts in the

fight against drug abuse and illicit trafficking, in line with the international drug control treaties.

44

Drug control legislation in Sweden, is in many respects stricter than what is required by the

treaties which do not, for example, require that drug use (as opposed to possession) be punished.

At the same time, such provisions are permissible and many Governments provide for stricter

sanctions in their national legislation than those required in the Conventions.

The vision of a drug-free society is not unique to Sweden but used to be shared by many of its

Nordic neighbours. The Action Plan to Combat Drug- and Alcohol-related Problems, adopted by

the Government of Norway in 2002, spells out that the “main vision forming the basis for the

Norwegian drug control policy is a society free from drugs and substance abuse.”

45

Finland, in

2002, was reported to have as its main goal of national drug control “to prevent drug use and the

proliferation of drugs so as to reduce the detrimental effects on individuals and the costs entailed

by drug abuse.”

46

Similarly, for several years, Iceland carried out a programme called “Drug-free

Iceland 2002”, under which several drug prevention activities were carried out and which is

considered a success in mobilizing the general public against drug abuse.

47

Only Denmark has always adopted a slightly different view. Already back in 1994, a joint policy

paper authored by the Ministries of Justice, Social Affairs and Health entitled “fight against drug

abuse-elements and problems”, states that “a drug-free society is seen as probably unrealistic”.

The same attitude is reflected in the 2003 Action Plan Against Drug Abuse, adopted by the Danish

Government in October of the same year which reads, in part, as follows: “It is evident that a

society without any drug abuse at all would be desirable, but from a realistic point of view this

must be considered as an unattainable goal. And no Government in any country has been able to

“solve” the problem of drugs.”

48

Nevertheless, the plan continues, one would be “totally mistaken

to assert that society’s efforts against drug abuse over several decades have failed, also because

unlimited resources have at no time been available for these efforts.”

49

Over the last few years, some Nordic countries seem to have adopted a similar approach,

especially those which are European Union members or associated members. Finland, for

example, now takes the view that “a drug free society is not a realistic objective for anti-drug

campaigns.”

50

The current main policy document makes no reference to the ideal of a drug-free

society and its objective is now to “bring about a permanent change for the better in the drug

situation in Finland.

51

Norway also appears to be moving away from the goal of a drug-free

society, especially with the introduction of drug injection rooms. According to the Government,

Part 1: The Swedish Drug Control Policy

21

drug injection rooms were in fact, also established to “facilitate an evaluation of the effect of

exemption from punishment for possessing and using drugs in a specifically delimitated area.”

52

At the level of the European Union, drug control strategies are very general in nature, leaving

much room for Member States to carry out their national policies. Neither the current EU Action

Plan on Drugs (2005-2008) nor the EU Strategy (2005-2012) make reference to a society free

from drug abuse, let alone, describe it as a guiding vision or principle.

The debate about the Swedish drug policy intensified after Sweden (as well as Austria and

Finland) joined the European Union in 1995. Of all three new European Union members, Sweden

was arguably pursing the most restrictive drug policy. Given its low rate of drug abuse compared

to other European Union Member States, the policy of Sweden was seen as successful and there

were repeated references to the Swedish model in drug policy discussions.

53

However, this

development was not welcomed by all. While the statement of one researcher that Sweden’s entry

into the European Union “paralyzed the general trend towards liberalism that had been

developing,”

54

is probably an overstatement, it is true that a harmonized European Union drug

policy remains an elusive goal. Nonetheless, States members of the European Union are parties to

the United Nations treaties and thus bound by their provisions.

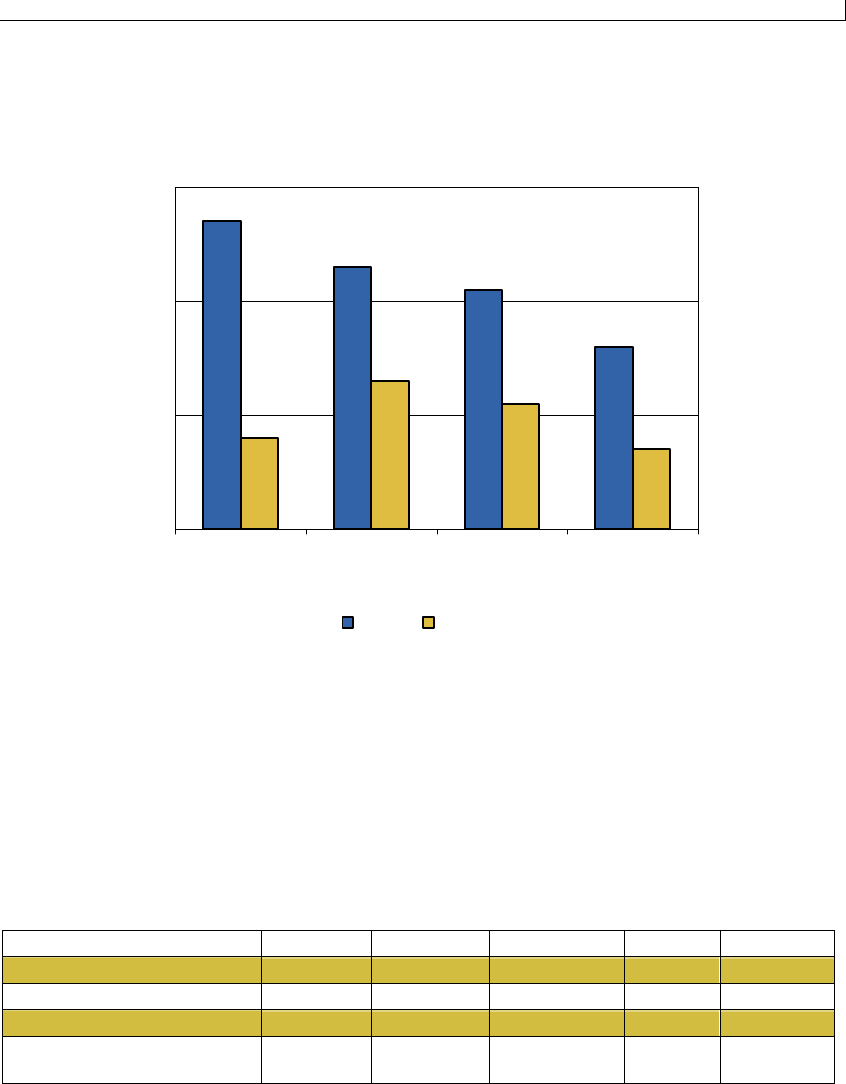

As regards investment into drug control policies, a study by the European Monitoring Centre on

Drugs and Drug Addiction showed that, after the Netherlands, Sweden has the highest drug-

related expenditure per capita in EUR and as percentage of GDP.

Table 1: Drug- related expenditure per capita in EUR and as percentage of GDP

Per capita % of GDP

Netherlands 139 0.66

Sweden 107 0.47

UK 68 0.35

Luxembourg 54 0.15

Ireland 49 0.27

Finland 31 0.15

Belgium 18 0.09

Austria 18 0.08

France 16 0.08

Denmark 14 0.05

Italy 11 0.06

Portugal 9 0.10

Spain 9 0.07

Germany 9 0.04

Greece 2 0.02

N/A = not available

Austria: 8,114,000 population and GDP of €181,937 million; Belgium: 10,214,000 population and GDP of €214,961

million; Denmark: 5,319,000 population and GDP of €148,975 million; Finland: 5,171,000 population and GDP of

€107,900 million; France: 59,099,000 population and GDP of €1,244,312 million; Germany: 82,087,000 population

and GDP of €1,870,714 million; Greece: 10,553,000 population and GDP of €106,742 million; Ireland: 3,745,000

population and GDP of €67,861 million; Italy: 56,952,000 population and GDP of €1,011,082 million; Luxembourg:

431,000 population and GDP of €15,410 million; Netherlands: 15,754,000 population and GDP of €332,513 million;

Portugal: 9,983,000 population and GDP of €92,031 million; Spain: 39,418,000 population and GDP of €492,989

million; Sweden: 8,868,000 population and GDP of €201,024 million; UK: 59,333,000 population and GDP of

€1,165,057 million

Source: adapted from Public expenditure on drugs in the European Union 2000-2004, EMCDDA, 2004

Part 2: The Drug Situation In Sweden

23

PART 2: THE DRUG SITUATION IN SWEDEN

The development of the drug problem at the national level will be reviewed in more detail to see

to what extent changes in drug policy have had an impact of drug use levels in Sweden.

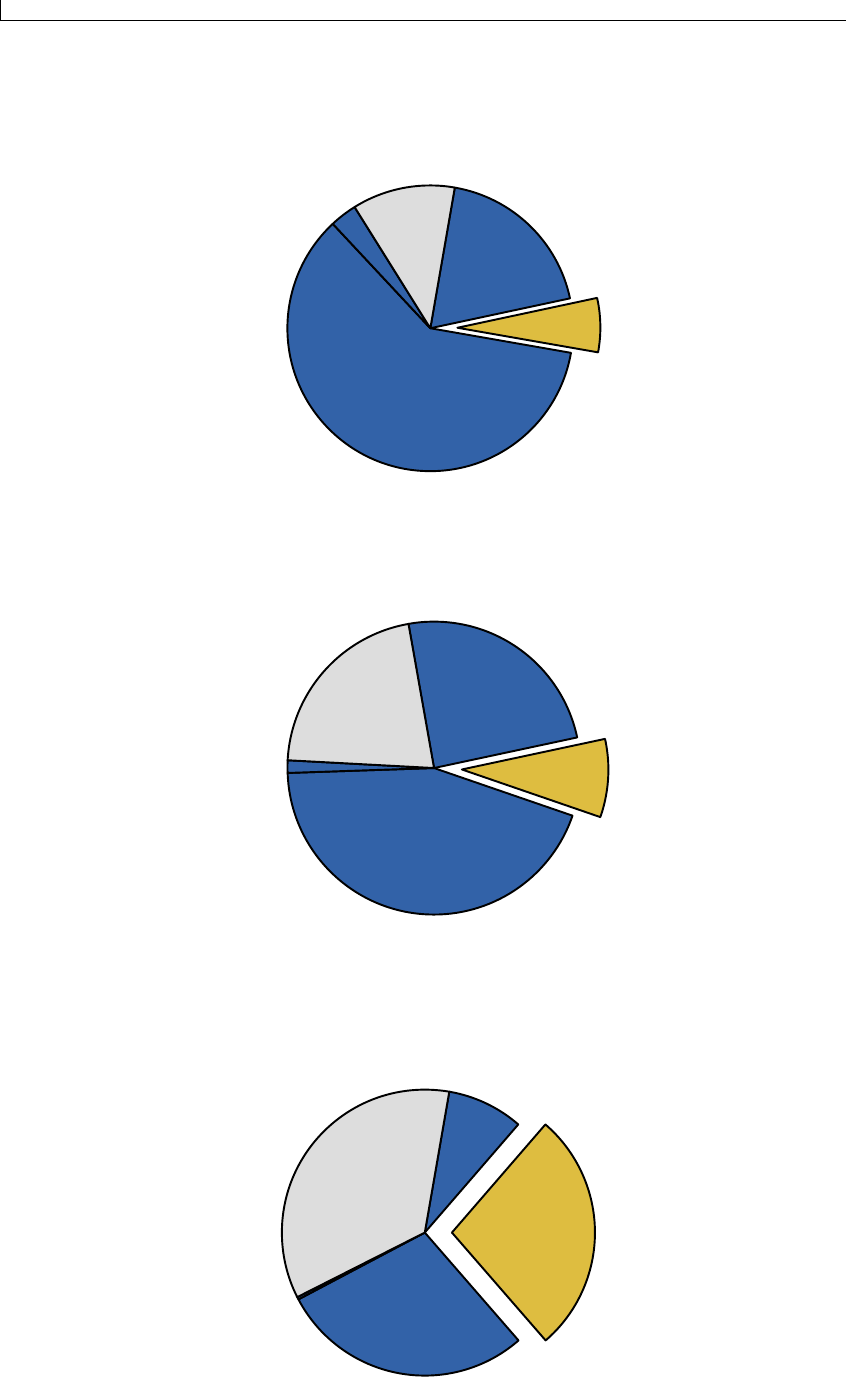

Amphetamine - the main problem drug

Unlike most European countries, the main problem drug in Sweden is not heroin but intravenously

administered amphetamine. As outlined above, Sweden was among the first countries in Europe to

experience a major amphetamine epidemic, dating back to the 1930s. Despite progress made in

curbing amphetamine use, amphetamine is still the main problem drug in the country.

Heroin, the main problem drug in Europe, was not known in Sweden until the late 1960s. While

its abuse has expanded over the years, heroin ranks second as a problem drug in Sweden. Cocaine

and ecstasy are of limited importance. As in most countries around the world, cannabis is the most

widely used drug among youth and the general population.

Data for treatment demand clearly show the predominant role of amphetamine abuse in Sweden.

Amphetamine (35.1 per cent) outranks opiates (31.5 per cent), with cannabis in third place (19.5

per cent). The proportion of amphetamine in treatment is in Sweden four times larger than in

Europe as a whole.

Figure 2: Drug-related treatment demand in Sweden, 2003

Amphetamines

35.1%

Ecstasy

0.5%

Cannabis

19.5%

Other

2.4%

Sedatives

9.0%

Cocaine

2.0%

Opiates

31.5%

Source: UNODC, Annual Reports Questionnaire Data.

Sweden’s successful drug policy: A review of the evidence

24

Figure 3: Drug related treatment demand in Europe, 2000-04

Opiates

58.5%

Cannabis

15.9%

Ecstasy

1.1%

Other

7.0%

Sedatives

2.5%

Cocaine

6.5%

Amphetamines

8.5%

Source: UNODC, 2006 World Drug Report

Development of amphetamine use from 1940 to date

The introduction of amphetamines, primarily benzedrine and methamphetamine (marketed as

pervitin), in about 1938 marked the beginning of a drug abuse problem in Sweden. Drugs were

heavily advertised (one popular slogan was “Two pills are better than a month’s vacation”), sold

freely and subsequently used by large sections of the population. Representative enquiries into

student behaviour in Sweden found a few years after their introduction into the Swedish market

that 70-80 per cent of students were occasional users of ‘pep pills’.

55

Although figures are not

directly comparable, in 2003, life-time prevalence of amphetamines among 15-16 year olds ini

Sweden was estimated at 1 per cent (2003 ESPAD study).

56

The introduction of a prescription requirement for amphetamine in 1939 did not lead to a sustained

reduction in use. Sales were halted only for about a year before skyrocketing again as people

collected prescriptions through third parties. The use of amphetamine began to rise continuously

and in 1943, almost 10 million tablets were consumed annually. At that time, the number of

amphetamine users was estimated at 200,000 users, equivalent to 4.6 per cent of the population

age 15-64.

The sales of amphetamine plunged, however, when the National Medical Board of Health issued a

warning on the risk and abuse of stimulants in April 1943. The decline, which has been estimated

at between 40 to 60 per cent, was caused, inter alia, by restrictive prescription practices.

Soon after 1943, the market for amphetamines recovered and abuse continued to spread. By the

late 50s, abuse of methylphenidate, a central-nervous system stimulant, was a great concern.

Dexamphetamine and phenmetrazine were also widely used as weight-reducing agents.

In 1959, the total number of amphetamine users peaked at 313,000 people or 6.4 per cent of the

population age 15-64, which is extremely large, even by today’s global standards. (The highest

level of amphetamines use worldwide is currently reported from the Philippines with an annual

prevalence rate of 6 per cent, followed by Australia with 3.8 per cent).

57

However, by 2000/2003, the total number of amphetamines users in Sweden was only a fraction of

what it had been in 1959, some 25,000 persons (UNODC estimate

58

) or 0.4 per cent of the

population age 15-64. The Swedish drug policy seems to have contributed to this decline.

Part 1: The Swedish Drug Control Policy

25

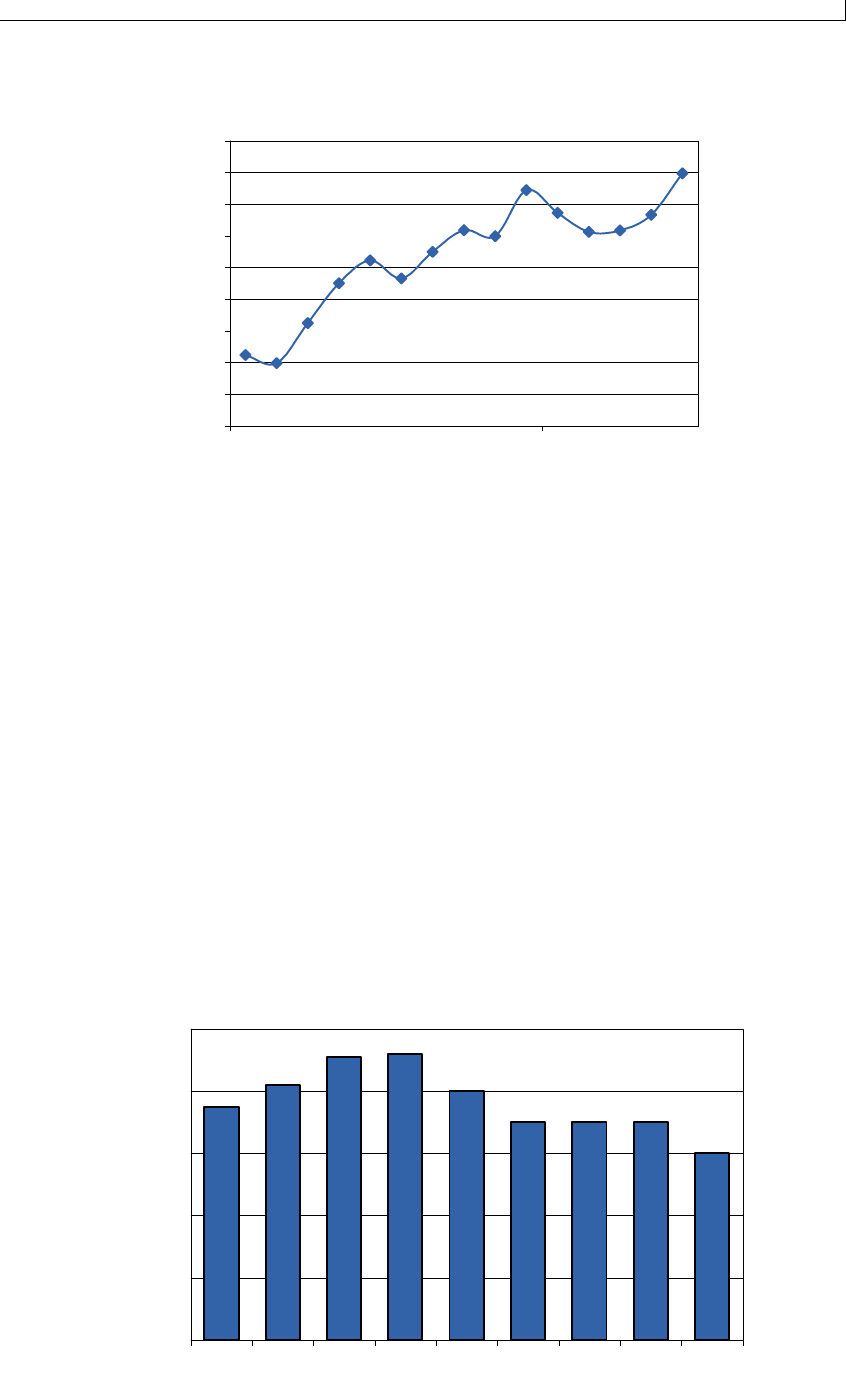

Figure 4: Amphetamine use in Sweden among the general population (age 15-64), 1943-

2003

4.6%

6.4%

1.7%

0.4%

3.2%

4.3%

1.2%

0.2%

0.0%

1.0%

2.0%

3.0%

4.0%

5.0%

6.0%

7.0%

1943 1959 1965 2000/03

all amphetamine use (incl. problem drug use)

occasional & regular use / annual prevalence

Sources: Börje Olsson, Narkotikaproblemets bakgrund – Användning av och uppfattningar om narkotika inom svensk medecin

1839-1965 (The Background of the Drug Problem – Use of and Conceptions about Narcotic Drugs in Swedish Medicine, 1939-

1965), Stockholm 1994; and UNODC, Annual Reports Questionnaire Data.

The massive decline in overall amphetamine use since the late 1950s, however, does not appear to

have been sufficient to reduce problematic use of amphetamines. An ever larger proportion of

amphetamine users eventually became dependent on the substance, partly linked to a trend

towards injecting amphetamine.

Estimates of the number of heavy amphetamine abusers were still rather low in 1959, at some

3,300 persons or 0.07 per cent of the population age 15-64). By 1965, this number had increased

to some 4,000 persons, despite stricter prescription requirements. Offering drugs, notably

amphetamines, to drug abusers, as was done in the Stockholm experiment, could not reverse this

trend. By 1969, the number of problem drug users had increased to 10,000. Given the fact that the

overwhelming majority used amphetamines, the number of amphetamine abuser is estimated at

8,000 persons.

The gradual restriction of the Swedish drug control policy after 1968 is associated with a fall in

both overall amphetamine use and problematic amphetamine use. In 1979, the number of problem

drug users was estimated at between 10,000-14,000 persons, of which an estimated 5,600 were

amphetamine abusers, equivalent to 0.11 per cent of the population age 15-64 - much lower than

in 1969.

No estimates on problem drug use are available for the 1980s, but it is generally assumed that

there was not much of an increase as rising drug budgets meant that ever more drug addicts

benefited from treatment.

This changed in the 1990s. By 1992, the overall number of problem drug users was estimated to

have increased to 17,000 (14,000-20,000), rising further to 26,000 by 1998 and 28,000 by 2001.

The proportion of amphetamine as the prime drug among problem drug users, however, continued

to decline, from 47 per cent in 1979 to 32 per cent in 1998.

59

Applying the ratio of 32 per cent to

the number of problem drug users in 2001, calculations suggest that there were some 9,000

amphetamine related problem drug users in Sweden, or 0.16 per cent of the population age 15-64.

Less than 26,000 persons were estimated to be problem drug users in 2003, which, assuming a

constant proportion of amphetamine in overall problem drug use, gives an estimate of 8,200

persons or 0.14 per cent of the population age 15-64 in 2003. This would be still more than

amphetamine-related problem drug use in 1959, 1965 or 1979 though at similar levels as estimates

for 1969.

Sweden’s successful drug policy: A review of the evidence

26

Drug use in Sweden since 1970

As shown above, Sweden experienced significant increases in amphetamine use in the 1940s and

1950s. This period was followed by major successes in curbing amphetamine use, notably over the

1959-65 period (more than 70 per cent), mainly by addressing the prescription practices of

medical doctors. Thus, within a five to six year period, Sweden’s extensive amphetamine use

levels have been on the way towards a gradual elimination. However, a number of new drugs

emerged and existing ones, notably cannabis and LSD, became widespread within short periods of

time.

Epidemiological data in Sweden has been collected systematically since the 1970s. The best

available data to monitor the impact of the drug policy are the regularly undertaken national

school surveys and the surveys on military recruits in Sweden.

Life-time prevalence of drug use among 15-16 year old students declined from 15 per cent in 1971

to 3 per cent in 1989. Past month prevalence rates showed an even steeper decline, falling by 90