Oxford Review of Education

ISSN: (Print) (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/core20

Pathways from the early language and

communication environment to literacy outcomes

at the end of primary school; the roles of language

development and social development

Jenny L. Gibson, Dianne F. Newbury, Kevin Durkin, Andrew Pickles, Gina

Conti-Ramsden & Umar Toseeb

To cite this article: Jenny L. Gibson, Dianne F. Newbury, Kevin Durkin, Andrew Pickles, Gina

Conti-Ramsden & Umar Toseeb (2021) Pathways from the early language and communication

environment to literacy outcomes at the end of primary school; the roles of language

development and social development, Oxford Review of Education, 47:2, 260-283, DOI:

10.1080/03054985.2020.1824902

To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/03054985.2020.1824902

© 2020 The Author(s). Published by Informa

UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis

Group.

Published online: 11 Nov 2020.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 5450

View related articles View Crossmark data

Citing articles: 4 View citing articles

Pathways from the early language and communication

environment to literacy outcomes at the end of primary

school; the roles of language development and social

development

Jenny L. Gibson

a

, Dianne F. Newbury

b

, Kevin Durkin

c

, Andrew Pickles

d

,

Gina Conti-Ramsden

e

and Umar Toseeb

f

a

Faculty of Education, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK;

b

Department of Biological and Medical

Sciences, Oxford Brookes University, Headington Campus, Oxford, UK;

c

Department of Psychology,

University of Strathclyde, Glasgow, UK;

d

Department of Biostatistics, Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology and

Neuroscience, King’s College London, London, UK;

e

School of Health Sciences, The University of Manchester,

Manchester, UK;

f

Department of Education, University of York, York, UK

ABSTRACT

The quality of a child’s early language and communication environ-

ment (ELCE) is an important predictor of later educational out-

comes. However, less is known about the routes via which these

early experiences inuence the skills that support academic

achievement. Using data from the Avon Longitudinal Study of

Parents and Children (n = 7,120) we investigated relations between

ELCE (<2 years), literacy and social adjustment at school entry

(5 years), structural language development and social development

in mid-primary school (7–9 years), and literacy outcomes (reading

and writing) at the end of primary school (11 years) using structural

equation modelling. ELCE was a signicant, direct predictor of social

adjustment and literacy skills at school entry and of linguistic and

social competence at 7–9 years. ELCE did not directly explain var

-

iance in literacy outcomes at the end of primary school, instead the

inuence was exerted via indirect paths through literacy and social

adjustment aged 5, and, language development and social devel

-

opment at 7–9 years. Linguistic and social skills were both predic-

tors of literacy skills at the end of primary school. Findings are

discussed with reference to their potential implications for the

timing and targets of interventions designed to improve literacy

outcomes.

KEYWORDS

Literacy; social relationships;

language; linguistics;

communication; longitudinal

Children’s early oral language skills are positively associated with later academic out-

comes (Bleses et al., 2016; Roulstone et al., 2011). This applies to many aspects of

academic performance but it is especially relevant to achievement in literacy (Durkin

et al., 2009). One reason for this is that oral language competencies in areas such as

phonology, vocabulary, syntax, non-literal language and story-telling can form a secure

foundation for reading comprehension and decoding (Bishop & Snowling, 2004; Bowyer-

CONTACT Umar Toseeb [email protected] Department of Education, University of York, York YO10 5DD,

UK

OXFORD REVIEW OF EDUCATION

2021, VOL. 47, NO. 2, 260–283

https://doi.org/10.1080/03054985.2020.1824902

© 2020 The Author(s). Published by Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/

licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly

cited.

Crane et al., 2008). Reading skills in turn facilitate children’s engagement with texts and

production of their own writing, on which formal academic assessment often depends. In

addition, linguistic skills enable a child to benet from direct instruction from a teacher,

which is typically delivered using linguistic means of communication.

There may also be inuences on literacy outcomes via the relations between oral

language skills and social development. Like oral language competence, early social

competence has been linked to later academic achievement, in this case via positive

school adjustment and engagement in collaborative learning with peers (Denham &

Brown, 2010; Taylor et al., 2004; Von Salisch et al., 2015). Moreover, social competence

has a close link to oral language competence (St Clair et al., 2011; Mok et al., 2014).

Linguistic and social competencies have a mutually inuential impact in early child

development. A child’s rst words emerge in the context of early caregiver interactions

(Carpenter et al., 1998). Later in toddlerhood and beyond, more advanced linguistic skills

give children tools to make friends and engage in play (Fujiki et al., 1999; Ho, 2006; Hoyte

et al., 2014; Rakoczy et al., 2006). In turn, these social competencies may enable children to

engage in peer learning opportunities (such as conversation or collaborative problem

solving), which are associated with more positive educational outcomes (Mercer & Howe,

2012; Vrikki et al., 2019).

Both language development and social development are not only inuenced by

individual dierences in underlying abilities but also by proximal and distal environmen

-

tal factors. Oral language development is dependent on the nature, frequency and quality

of early communicative experiences provided by the main caregiver and others

(Huttenlocher et al., 2010; Romeo et al., 2018). These proximal inuences on early

linguistic development comprise a diverse and complex range of factors such as the

activities and support that caregivers provide to scaold early communication (e.g.,

talking to, reading or playing with, or singing to a child), alongside consideration of the

economic resources that families put into communication-relevant activities, for example,

books, toys or visits to the library (Roulstone et al., 2011). Reecting the reciprocal

inuences discussed above, high-quality early environments have also been shown to

be good predictors of social skills development (Rose et al., 2018), while parental beha

-

viours that support language development also support social development.

Given that provision of a high-quality early learning environment draws on both

temporal and nancial resources, the construct should also be considered with reference

to socioeconomic status (SES). Deleterious eects of poverty have been consistently

observed for children’s language development and social development (Bradley &

Corwyn, 2002; Ho, 2003; Law et al., 2019) as well as for literacy outcomes (Feinstein,

2003; Jerrim et al., 2015). Even so, a recent analysis has shown that while SES is an

inuential factor, good quality early learning environments can be created even in

resource-limited families (Law et al., 2019). That is: while the availability of resources is

signicant, good use of whatever is available is more important (Ho, 2003).

An array of factors, then, including environmental quality, SES and material resources,

individual dierences in the pace of linguistic and social development, bear on the skills

a child has at the time of entry to school and contribute to ‘school readiness’. The construct

of school readiness captures the extent to which a child is ready to thrive in the context of

formal schooling (Snow, 2006). It can be viewed across several domains, including academic

competences such as literacy and numeracy, and so-called ‘non-cognitive’ or ‘learning

OXFORD REVIEW OF EDUCATION 261

readiness’ skills such as social awareness, self-regulation, independence and persistence in

problem-solving (Blair & Raver, 2015; Carton & Winsler, 1999; Denham, 2006; Fink et al.,

2019).

Findings regarding the relative contributions of these dierent skill domains at school

entry have been mixed. Konold and Pianta (2005) found that children characterised by

a high level of social skill at school entry tended to do better than most other groups on

academic outcomes measured after the rst year of school. On the other hand, a meta-

analysis of six longitudinal cohort studies (drawn from Canada, UK and USA), using school

entry assessments as predictors of academic achievement, found moderate eects for early

number skills, small eects for early literacy and language skills and null eects for early

social skills (Duncan et al., 2007). Interestingly, however, a replication of this meta-analysis in

the Canadian data, using multiple imputation to account for missing datapoints, found that

social adjustment at school entry did in fact predict academic achievement (Romano et al.,

2010). Furthermore, the original Duncan study aggregated outcome measures from quite

a wide age range from age 7–8 years to 13–14 years, depending on the available data in

each cohort. Therefore, some of the variability across domains may be due to the age of

assessment; theorists have suggested that the inuences of social competencies on learning

may increase as children get older (Denham & Brown, 2010). In light of these mixed ndings,

there is still work to be done in understanding how the skills in dierent domains that

children have at school entry develop in concert over time, and in identifying the pathways

via which early environmental factors exert inuence over the later linguistic and social

competencies that ultimately aect academic outcomes.

The current study

In the current study, we used a large cohort dataset, the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents

and Children (ALSPAC), to investigate the relative importance of linguistic and social

inuences on achievement in literacy at the end of primary school. Our thesis is that

a positive early language and communication environment (ELCE) initiates a ‘virtuous

cycle’ whereby early social and communicative experiences boost individual development

in these domains, thus supporting school readiness. We consider the features of a positive

early language and communication environment to be parental resources and behaviours

that provide optimal conditions for child language development (Bradley & Corwyn, 2002;

Son & Morrison, 2010). This might include parental sensitive and contingent responding,

engaging the child in play and other one-to-one activities, and emotional warmth (Son &

Morrison, 2010). In turn, skills at school entry enable children to capitalise on opportunities

in the school environment, further promoting linguistic and social development and

ultimately supporting academic attainment at the transition to high school.

We need also further evidence to address the fascinating possibility that, as children

progress through primary school, learning may be increasingly inuenced by dierent

domains of development or that the impact of development in dierent domains upon

learning may vary over time. Oral structural language skills (i.e. expressive and receptive

competence in morphosyntax and semantics) have been traditionally linked to literacy

achievement but their relative importance when compared to social inuences on literacy

at dierent stages of development is not clear. Therefore, we plan to compare the relative

inuence of oral structural language skills with the inuence of social competences upon

262 J. L. GIBSON ET AL.

literacy outcomes. Given that performance in reading is strongly linked to decoding skills

(Castles et al., 2018), we include this, along with performance IQ, in our model even though

they are not variables of primary interest to the current study. Note that in the current study

we use the term ‘literacy outcomes’ as a shorthand for academic performance in reading

and writing.

To achieve these aims we adopt a longitudinal, community-based cohort approach.

Modelling of children’s development and achievement over time allows us to address the

following predictions:

We expect to nd a direct eect of early environmental inuences on academic and

social school readiness at school entry, on linguistic and social development in middle-

primary school and also on literacy attainment at age 11 years. We also expect that

indirect paths from linguistic and social abilities may dierentially impact on academic

performance in literacy outcomes at the end of primary school. Based on the weight of

previous evidence, we predict stronger eects of linguistic ability, compared to social

abilities, on literacy outcomes.

Materials and methods

Ethical approvals

Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents

and Children (ALSPAC) Ethics and Law Committee and the Local Research Ethics

Committees. Ethical approval for the secondary analysis of existing ALSPAC data was

obtained from the University of York Education Ethics Committee (reference: 18/5).

Study sample

Data from the ALSPAC sample were used in this study (Boyd et al., 2013; Fraser et al., 2013).

All pregnant women in the old administrative region of Avon, whose estimated delivery was

between April 1991 to December 1992, were eligible to participate. The ALSPAC enrolled

sample consisted of 15,454 pregnancies, which resulted in a total number of 15,589 children

(including multiple births). Of these, 14,901 were alive at 1 years of age. Parents and children

provided biological samples, questionnaire data, and took part in direct assessments. Full

details of the cohort are reported elsewhere. The study website contains details of all the

data that are available and provides a fully searchable data dictionary and a variable search

tool (http://www.bristol.ac.uk/alspac/researchers/our-data/).

A number of exclusionary criteria were applied: second-born children, those who did

not take part in the speech and language session at age 8 years, and those with

a performance IQ below 60 were removed (n = 8,325). This resulted in a nal sample

size of 7,120 (50% boys).

Measures

Early language and communication environment (ELCE, 18–24 months)

When the child was aged 18–24 months, ELCE was assessed using a measure previously

used by Roulstone et al. (2011). Higher scores on the measure are indicative of richer

OXFORD REVIEW OF EDUCATION 263

home environmental support for language and communication. The ELCE measure

includes ve subscales: mother-child direct teaching (e.g., mum teaches songs), mother-

child activities (e.g., frequency mum has physical play with child), child’s interactions with

others (e.g., child sung to), resources (e.g., number of toy vehicles a child has at home),

and other activities (e.g., frequency child taken to park). The composite sum scores from

these ve subscales were used to create a continuous latent variable within a structural

equation modelling (SEM) framework (CFI =.952, TLI = .904, RMSEA = .063, SRMR = .028).

Full details of the measure are provided in Appendix A.

Early socio-economic status (SES)

A composite measure of socioeconomic status was taken from Roulstone et al. (2011) and

adapted (car ownership question removed because 95% of the sample owned a car). The

measure consisted of a number of parent-report questions, which were taken at 8- and 32-

weeks gestation. They were coded as described in Roulstone et al. (2011). Responses were

coded on a binary scale for paternal occupation (0 = manual, 1 = non manual), maternal

education (0 = lower than A level, 1 = A level or higher), house tenure (0 = not owned,

1 = owned), home overcrowding (0 = more than one person per room, 1 = less than one

person per room), and nancial diculties (0 = nancial diculties reported, 1 = no nancial

diculties reported). These binary variables were then summed to create an early SES score

ranging from 0 to 5. Higher scores indicate higher SES.

School entry measures (4–5 years)

Children in the UK usually begin school by starting in ‘Reception’ class in the September

following their fourth birthday and then transition into formal schooling in ‘Year 1ʹ during

their fth year of life. Although at the time the ALSPAC children reached Reception-age

there were no statutory assessments, the local region had its own school entry assess

-

ments, and these were used in the current study. We have used these assessments as

teacher-rated school readiness indicators in the domains of social adjustment and literacy.

Each assessment area was teacher-rated on a scale of 2–7 with higher scores indicating

greater competence. Assessments were carried out in the rst half-term following entry

once teachers were satised the children were settled. Two measures from these assess

-

ments were used in the analyses reported here:

Literacy at school entry. This latent variable (described in the statistical analyses section)

comprises early reading and writing skills as rated during the reception year.

Social adjustment at school entry. This observed variable is the teacher assessment of

the child’s social adjustment in the rst half-term after school-entry.

Mid-primary school measures (7–9 years)

At the mid-point of primary school, measures of linguistic and social development were

taken. These were a combination of in-clinic assessments and parent-report:

Language development at age 8 years. This was based on measures of expressive and

receptive language skills. These skills were measured using subtests from the Weschler

Objective Language Dimensions (WOLD; Rust, 1996) and were carried out via direct

264 J. L. GIBSON ET AL.

assessment with each child. The expressive language task was a 10-item picture naming

task and the receptive language task involved being shown a complex picture, listening to

a paragraph about it, and subsequently being asked 16 comprehension questions about

what the child had heard. For both tests, incorrect responses were scored as 0 and correct

responses were scored as 1. Scores were then summed to create a score ranging from 0 to

10 for expressive language and 0 to 16 for receptive language. Composite sum scores for

both measures of language development were used to create a latent variable for

language ability (as described in the statistical analyses section).

Social development. This was based on three measures: play skills, prosociality and

pragmatic language, which were combined to generate a latent variable (as described

in the statistical analyses section).

Play skills at 7 years. Parents were asked to rate their child’s social play skills such as

sharing toys and easily taking turns in a game. There were eight items and the responses

to each item were recoded onto a two-point scale (1 = yes but not well, 2 = yes can do well)

and a mean score was calculated. Scores ranged between 1 and 2, with higher scores

indicating higher levels of skill in play-based interactions.

Prosociality at 7 years. The prosociality scale was based on parental ratings on the

Strengths and Diculties Questionnaire (SDQ) prosocial subscale (Goodman, 1997),

which consists of ve statements rated on a three-point scale (0 = not true, 1 = somewhat

true, 2 = certainly true). Scores ranged from 0 to 10 with higher scores showing higher

levels of prosociality.

Pragmatic language at 9 years. The Children’s Communication Checklist (Bishop, 1998)

was used to assess pragmatic language. This is a parental rating of child communication

skills. The following subscales were summed to form the pragmatic score: inappropriate

initiation, coherence, stereotyped conversation, use of conversational context, and conversa

-

tional rapport. Higher scores indicate greater pragmatic language ability. The pragmatic

scale was included in the social development latent variable as it involves the social use of

language (for example, in a conversation) rather than the more traditional ‘structural’

measures of comprehension and expression indexes in the language development variable.

Of course, pragmatics also relies on linguistic skills and the distinction is not absolute; for this

reason, we co-varied the language development and social development latent variables in

our model (see statistical analyses section).

Performance IQ at age 8 years. The Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children (WISC:

Wechsler, 1991) was used to assess performance IQ (PIQ). To generate a performance IQ

score, the ve performance subtests were used: picture completion, coding, picture

arrangement, block design, and object assembly. The raw scores were standardised

using the WISC manual to generate an age-appropriate score for each child. Higher scores

indicated higher performance IQ.

Decoding skills at age 9 years. This was assessed face-to-face by asking the child to read

out 10 words and 10 non-words. Both types of words were taken from a larger battery of

words (Nunes et al., 2003). Incorrect responses were coded as 0 and correct responses

were coded as 1. These were summed to create a score out of 10 for words and the same

for non-words with higher scores indicating better reading ability. These two scores were

OXFORD REVIEW OF EDUCATION 265

then combined to generate a latent variable for decoding skills (as described in the

statistical analyses section).

End of primary school literacy outcomes (11 years)

The literacy outcomes measures are based on statutory national assessments that all

children in England complete at the end of primary school (key stage 2). The ALSPAC

study team obtained data from the National Pupil Database (NPD, the English national

record of educational achievement for children in state schools) and linked it with the

data for each child. In the present study, we used scores from key stage 2 reading and

writing assessments to compute a latent variable, literacy outcomes.

Statistical analyses

A SEM approach was used to address the research questions. Prior to implementing the

SEMs, a theoretical model specifying the relations and pathways we expected to see

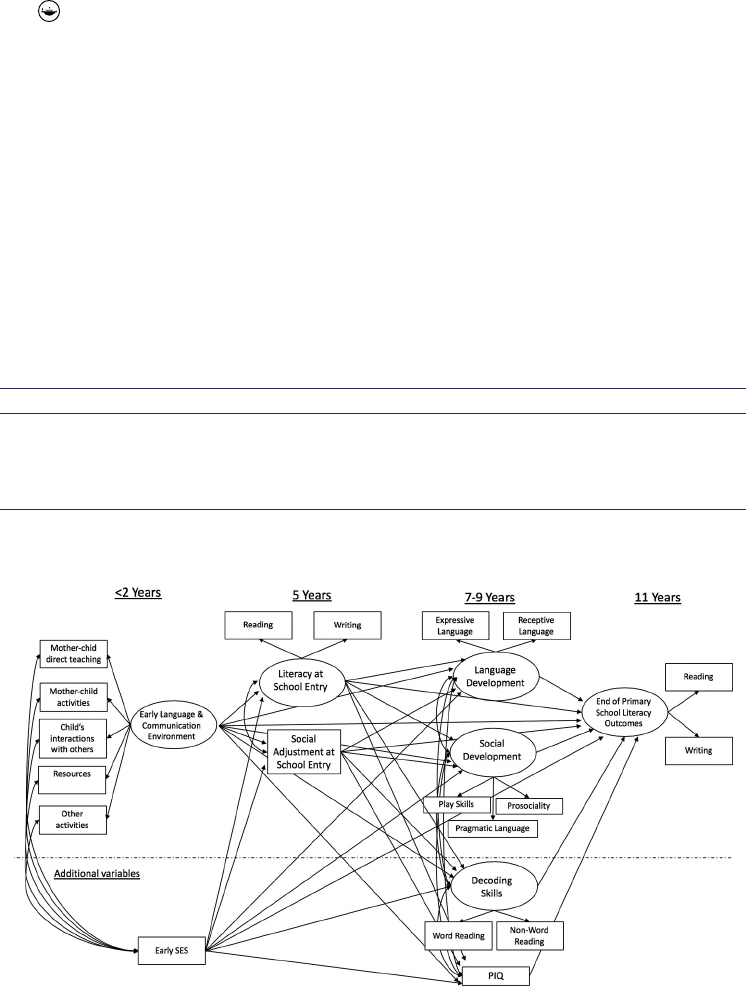

between the study variables was constructed (see Figure A1 in Appendix).

The SEM model was specied in Mplus version 7.3 (Muthen & Muthen, 2012). All other

analyses were run in Stata/MP 16 (StataCorp, 2019). Pathways between the ELCE and end

of primary school literacy outcomes were investigated. This included direct paths and also

indirect paths via social school readiness (4–5 years) and a number of latent variables:

literacy at school entry (4–5 years), language development (8 years), and social develop

-

ment (7–9 years). We also included direct and indirect paths via covariates such as

performance IQ (8 years) and decoding skills (9 years). Latent variables can be interpreted

in the same way as composite sum scores but with less measurement error. This is

because the extent of the associations between the subscales and the continuous latent

variable can vary, whereas with a composite sum score this is not possible. Taking the

example of the ELCE, in a composite sum score, it is assumed that all ve subscales

contribute equally to ELCE. In a latent variable, if one of the subscales is more important

for ELCE then this is accounted for in the model.

SEM models allow for a measurement (i.e., the latent factor modelling) and structural

model (i.e., the path analysis) to be run concurrently within a single model. The measure

-

ment model allows for an account to be taken of measurement errors that would

otherwise downwardly bias the apparent strength of association between the predictor

and outcome. Individual items were not loaded directly onto the latent factors. Instead,

a method known as parcelling was used. To do this, rst, composite sum scores were

created for each of the constituent variables for any given latent variable and these scores

were treated as observed variables for the purposes of the latent factor loadings. In total,

there were six latent variables in the SEM; ELCE (mother-child direct teaching, mother-

child activities, child’s interactions with others, resources, and other activities), literacy at

school entry (reading and writing), language development in mid-primary school (expres

-

sive and receptive language), social development in mid-primary school (play skills,

prosociality, and pragmatic language), decoding skills (word reading and non-word read

-

ing), and end of primary school literacy outcomes (reading and writing).

The MLR estimator, which is robust to non-normality, was used in the SEM. Residual

variances for all latent variables at age 5 years and 7–9 years were correlated with all

others at the same time point to account for the overlap between the constructs. The

266 J. L. GIBSON ET AL.

MODEL INDIRECT command was used to test for indirect paths between ELCE and end of

primary school literacy outcomes. All indirect paths were tested rather than just when

there was a signicant main eect; the indirect paths were calculated post-hoc using the

delta method. This is in line with other literature that uses a similar approach and allowed

potential suppressor eects to be revealed (St Clair et al., 2015; MacKinnon, 2000).

Missing data

Given the nature of longitudinal studies, sample attrition is almost inevitable. The ALSPAC

sample was no exception as there was sample attrition and thus missing data. We

compared children who took part at both age 1 and also at the end of primary school.

There was no signicant gender dierence in sample attrition (χ

2

(1, N = 14,854 = .13,

p = .723) between the sample at 1 years old and those with literacy outcomes data at the

end of primary school. For those who dropped out, socioeconomic status was lower (t

(13,957) = 6.61, p < .001) compared to those who continued to participate at the end of

primary school. For the SEM, the full information maximum likelihood method was used

to deal with missing data.

Results

Pairwise correlations between all variables of interest and descriptive statistics are

shown in Tables 1 and 2, respectively. The nal SEM is shown in Figure 1 (CFI = .965,

TLI = .949, RMSEA = .033, SRMR = .033). A full list of coecients for all paths and factor

loadings are provided in Table 3 and the indirect eects are shown in Table 4. For

precision, the path coecients in this section, and in Tables 3 and 4, are reported to

three decimal places.

The eect of ELCE on school readiness at school entry, language development and

social development in the middle-years of primary school

As shown in Table 3, ELCE was associated with literacy at school entry (β = .225, 95% CI:

.193, .256) and social adjustment at school entry (β = .090, 95% CI:.053, .127); as well as

language development (β = .118, 95% CI: .086, .150), social development (β = .247, 95% CI:

.208, .286), performance IQ (β = .039, 95% CI: .003, .055), and decoding skills (β = .087, 95%

CI: .058, .116) in the middle years of primary school. In short, a richer ELCE was associated

with more favourable school readiness in literacy and social adjustment, language devel

-

opment and social development, and performance IQ and decoding skills in the middle

years of primary school.

As expected, higher pre-natal socioeconomic status was associated with better literacy

(β = .312, 95% CI: .286, .338) and social adjustment at school entry (β = .157, 95% CI: .127,

.188) as well as better language development (β = .196, 95% CI: .168, .225) and social

development (β = .128, 95% CI: .090, .167), and performance IQ (β = .139, 95% CI: .117,

.162) and decoding skills (β = .149, 95% CI: .125, .173) in the middle years of primary

school. Therefore, early socioeconomic status and ELCE each make a unique contribution

to subsequent outcomes at school entry and middle years of primary school.

OXFORD REVIEW OF EDUCATION 267

Table 1. Pairwise correlations between all variables of interest.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18

1. Mother-child direct teaching 1

2. Mother-child activities .36*** 1

3. Child’s interactions with others .30*** .45*** 1

4. Resources .09*** .18*** .26*** 1

5. Other activities .16*** .25*** .25*** .20*** 1

6. Early socioeconomic status (< 2 years) .07*** .10*** .20*** .17*** .15*** 1

7. Reading (5y) .13*** .10*** .19*** .09*** .10*** .25*** 1

8. Writing (5y) .12*** .10*** .15*** .05** .10*** .19*** .55*** 1

9. Social adjustment at school entry (5y) .07** .05* .11*** .05* .10*** .14*** .49*** .47*** 1

10. Receptive language (8y) .06*** .07*** .11*** .10*** .06*** .19*** .21*** .15*** .15*** 1

11. Expressive language (8y) .10*** .10*** .19*** .10*** .07*** .24*** .30*** .24*** .18*** .40*** 1

12. Play skills (7y) .07*** .11*** .12*** .08*** .05*** .09*** .12*** .11*** .14*** .07*** .12*** 1

13. Prosociality (7y) .10*** .12*** .11*** .02 .05*** .00 .05** .08*** .13*** .03* .04** .34*** 1

14. Pragmatic language (9y) .07*** .10*** .15*** .11*** .08*** .20*** .18*** .18*** .20*** .13***

.19*** .26*** .20*** 1

15. Performance IQ (8y) .08*** .05*** .13*** .13*** .08*** .24*** .29*** .26*** .19*** .24*** .35*** .13*** .03** .17*** 1

16. Word reading (9y) .11*** .09*** .17*** .07*** .08*** .22*** .26*** .24*** .18*** .23*** .37*** .13*** .03 .23*** .27*** 1

17. Non-word reading (9y) .08*** .07*** .13*** .07*** .04** .17*** .20*** .18*** .13*** .17*** .29*** .10*** .01 .17*** .23*** .72*** 1

18. Reading (11y) .14*** .11*** .22*** .08*** .14*** .32*** .40*** .35*** .29*** .35*** .48*** .16*** .07*** .29*** .42*** .61*** .49*** 1

19. Writing (11y) .11*** .10*** .18*** .04** .13*** .27*** .36*** .35*** .27*** .21*** .34*** .12*** .08*** .25*** .31*** .53*** .45*** .67***

*** p < .001, **p < .01, * p < .05.

268 J. L. GIBSON ET AL.

Direct pathways from ELCE, early SES, and language development and social

development to end of primary school literacy outcomes

There was a direct eect from early socioeconomic status to end of primary school literacy

outcomes (β = .057, 95% CI: .037, .076). There was not, however, a residual direct eect

between ELCE and end of primary school literacy outcomes (β = −.009 95% CI: −.032,

Table 2. Summary statistics for all variables of interest.

n Mean (SD) Range

Early language and communication environment (18–24 months)

Mother-child direct teaching 6,425 8.05 (1.56) 0–10

Mother-child activities 6,409 32.84 (3.22) 14–40

Child’s interactions with others 6,234 28.10 (2.07) 5–30

Resources 6,230 21.53 (2.16) 6–24

Other activities 6,408 8.38 (1.92) 2–15

Early socioeconomic status (< 2 years) 6,765 8.38 (1.92) 0–5

School entry measures (5 years)

Reading 4,787 5.25 (.85) 2–7

Writing 4,788 5.04 (.84) 2–7

Social adjustment 2,459 5.57 (1.02) 2–7

Mid-primary school measures (7–9 years)

Receptive language 7,113 7.49 (1.94) 2–15

Expressive language 7,091 7.47 (1.80) 0–10

Play skills 5,830 1.74 (.19) 1–2

Prosociality 5,715 8.21 (1.71) 0–10

Pragmatic language 5,557 151.32 (7.16) 98–162

Performance IQ 7,120 99.98 (16.71) 60–151

Word reading 6,371 7.63 (2.38) 0–10

Non-word reading 6,368 5.29 (2.47) 0–10

End of primary school literacy outcomes (11 years)

Reading 6,047 31.36 (8.29) 0–49

Writing 6,049 27.81 (7.85) 2–50

Figure 1. Pathways to end of primary school literacy outcomes. Dot-dashed lines depict non-

significant paths. Solid lines depict significant direct paths at p <.05 or lower. Bold solid lines depict

significant indirect pathways at p <.05 or lower. Note. The covariance arrows between all the

mediators at age 5 and 7–9 years have been removed to make the figure clearer. The coefficients

for these covariances are shown in Table 3.

OXFORD REVIEW OF EDUCATION 269

Table 3. Coefficients for structural equation model.

Standardised β coefficients [95% Confidence

Intervals]

Latent variable factor loadings

Mother-child direct teaching → ELCE .473 [.448,.498]

Mother-child activities →ELCE .664 [.640,.688]

Child’s interactions with others →ELCE .691 [.662,.719]

Resources →ELCE .326 [.297,.355]

Other activities →ELCE .382 [.358,.405]

Reading → literacy at school entry .771 [.753,.790]

Writing → literacy at school entry .709 [.690,.728]

Receptive language →language development .529 [.510,.548]

Expressive language →language development .751 [.732,.771]

Play skills → social development .589 [.544,.633]

Prosociality → social development .472 [.430,.514]

Pragmatic language → social development .533 [.484,.583]

Word reading → decoding skills .942 [.931,.952]

Non-word reading → decoding skills .769 [.757,.780]

Reading → end of primary school literacy outcomes .902 [.893,.911]

Writing → end of primary school literacy outcomes .746 [.735,.758]

Path coefficients

ELCE → literacy at school entry .225 [.193,.256]

ELCE → social adjustment at school entry .090 [.053,.127]

ELCE → language development .118 [.086,.150]

ELCE → social development .247 [.208,.286]

ELCE → performance IQ .039 [.003,.055]

ELCE →decoding skills .087 [.058,.116]

ELCE → end of primary school literacy outcomes −.009 [−.032,.014]

Early SES → literacy at school entry .312 [.286,.338]

Early SES → social adjustment at school entry .157 [.127,.188]

Early SES → language development .196 [.168,.225]

Early SES → social development .128 [.090,.167]

Early SES → performance IQ .139 [.117,.162]

Early SES →decoding skills .149 [.125,.173]

Early SES → end of primary school literacy outcomes .057 [.037,.076]

Literacy at school entry → language development .461 [.402,.520]

Literacy at school entry → social development .145 [.072,.217]

Literacy at school entry → performance IQ .371 [.324,.418]

Literacy at school entry → decoding skills .357 [.307,.407]

Literacy at school entry → end of primary school literacy outcomes .235 [.191,.278]

Social adjustment at school entry → language development −.092 [−.149, −.035]

Social adjustment at school entry → social development .155 [.084,.226]

Social adjustment at school entry → performance IQ −.079 [−.127, −.032]

Social adjustment at school entry → decoding skills −.068 [−.119, −.018]

Social adjustment at school entry → end of primary school literacy

outcomes

−.016 [−.056,.024]

Language development → end of primary school literacy outcomes .278 [.244,.313]

Social development → end of primary school literacy outcomes .076 [.044,.108]

Performance IQ → end of primary school literacy outcomes .085 [.065,.105]

Decoding skills → end of primary school literacy outcomes .452 [.427,.477]

Residual correlations

Mother-child direct teaching with early SES .099 [.075,.124]

Mother-child activities with early SES .142 [.113,.171]

Child’s interactions with others with early SES .274 [.241,.308]

Resources with early SES .171 [.148,.194]

Other activities with early SES .154 [.131,.177]

Literacy at school entry with social adjustment at school entry .630 [.600,.661]

Language development with social development .140 [.089,.190]

Language development with performance IQ .320 [.293,.348]

Language development with decoding skills .372 [.340,.403]

Social development with performance IQ .108 [.074,.141]

Social development with decoding skills .156 [.112,.201]

Performance IQ with decoding skills .166 [.142,.189]

270 J. L. GIBSON ET AL.

Table 4. Coefficients for mediated effects in structural equation model.

Standardised β coefficients

[95% Confidence Intervals]

Proportion of effect

explained (%)

Indirect paths

ELCE → literacy at school entry→ end of primary school literacy outcomes .053 [.040,.065] 26%

ELCE → social adjustment at school entry → end of primary school literacy outcomes −.001 [−.005,.002] n/a

ELCE → language development → end of primary school literacy outcomes .033 [.023,.043] 16%

ELCE → social development → end of primary school literacy outcomes .019 [.010,.027] 9%

ELCE → performance IQ → end of primary school literacy outcomes .002 [.000,.005] 1%

ELCE → decoding skills → end of primary school literacy outcomes .039 [.026,.053] 19%

ELCE → literacy at school entry→language development → end of primary school literacy outcomes .029 [.022,.035] 14%

ELCE → literacy at school entry →social development → end of primary school literacy outcomes .004 [.002,.001] 2%

ELCE → literacy at school entry →performance IQ→ end of primary school literacy outcomes .002 [.001,.004] 1%

ELCE → literacy at school entry→decoding skills → end of primary school literacy outcomes .036 [.029,.044] 17%

ELCE → social adjustment at school entry→ language development →end of primary school literacy outcomes −.002 [−.004, −.001] 1%

ELCE → social adjustment at school entry→ social development →end of primary school literacy outcomes .001 [.000,.002] 0%

a

ELCE → social adjustment at school entry→ performance IQ →end of primary school literacy outcomes −.001 [−.001,.000] n/a

ELCE → social adjustment at school entry→ decoding skills →end of primary school literacy outcomes −.003 [−.005,.000] n/a

The last column is only populated for indirect effects that were significant.

a

the value here is 0.485, which is rounded down to 0%.

OXFORD REVIEW OF EDUCATION 271

.014). Both language development (β = .278, 95% CI: .244, .313) and social development

(β = .076, 95% CI: .044, .108) predicted end of primary school literacy outcomes but the

eect of language development was stronger (χ

2

(1, N = 7,120) = 7.12, p = .008)

Indirect pathways from ELCE to end of primary school literacy outcomes

As shown in Table 4, there were a number of indirect pathways between ELCE and literacy

outcomes at the end of primary school. At school entry, there was a signicant indirect

pathway via literacy (β = .053, 95% CI: .040, .065) but not social adjustment (β = −.001, 95%

CI: −.005, .002). There were also signicant indirect pathways via language development

(β = .023, 95% CI: .023, .043), social development (β = .019, 95% CI: .010, .027), perfor

-

mance IQ (β = .002, 95% CI: .000, .005), and decoding skills (β = .039, 95% CI: .026, .053) in

the middle-primary school years. Language development was not a stronger mediator

than social development of the relationship between ELCE and end of primary school

literacy outcomes (χ

2

(2, N = 7,120) = .55, p = .758). In sum, a richer ELCE was associated

with better academic and social school readiness, as measured by literacy and social

adjustment at school entry, but only academic school readiness was subsequently asso

-

ciated with better literacy outcomes at the end of primary school. Similarly, a richer ELCE

was associated with higher levels of language development and social development in

the middle years of primary school which, in turn, are associated with better literacy

outcomes at the end of primary school.

In addition to the independent indirect pathways from ELCE to end of primary school

literacy outcomes via literacy at school entry and language development and social

development in middle-primary school years, there were also further eects. There was

a signicant indirect eect from ELCE to end of primary school literacy outcomes via

literacy at school entry and language development in middle-primary school (β = .029,

95% CI: .022, .035). This was also the case for literacy at school entry and social develop

-

ment in middle-primary school years (β = .004, 95% CI: .002, .004). These ndings reveal

that a richer ELCE is associated with better literacy skills at school entry, which in turn are

associated with better language development and social development in the middle

years of primary school, which in turn are associated with better literacy outcomes at the

end of primary school.

The equivalent eects were also observed for social adjustment at school entry. There

was a signicant indirect eect from ELCE to end of primary school literacy outcomes via

social adjustment at school entry and language development in middle-primary school

(β = −.002, 95% CI: −.004, −.001). This was also the case for social adjustment at school

entry and social development in middle-primary school years (β = .001, 95% CI: .000, .002).

Therefore, a richer ELCE is associated with better social skills at school entry, which in turn

are associated with better language development and social development in the middle

years of primary school, which in turn are associated with better literacy outcomes at the

end of primary school.

We had anticipated that the indirect pathway from the ELCE via literacy at school entry

and language development aged 7–9 years to literacy outcomes at the end of primary

school would be stronger than the indirect pathway from the ELCE via social adjustment

at school entry and language development in middle-primary years to literacy outcomes

at the end of primary school. We found no evidence to support this expectation, χ

2

(2,

272 J. L. GIBSON ET AL.

N = 7,120) = 1.74, p = .419. Similarly, we expected that the indirect pathway from the ELCE

via literacy at school entry and social development in middle-primary years to literacy

outcomes at the end of primary school would be stronger than the pathway from the

ELCE via social adjustment at school entry and social development in middle-primary

years to literacy outcomes at the end of primary school. Again, we found no evidence to

support this expectation (χ

2

(2, N = 7,120) = .12, p = .40). These results do not support our

hypothesis that academic school readiness in literacy may exert stronger indirect eects

via support for later language development.

There was a signicant indirect eect from ELCE to end of primary school literacy

outcomes via literacy at school entry and performance IQ in middle-primary school

(β = .002, 95% CI: .001, .004). A signicant eect was not observed, however, when we

examined the relationship between social adjustment at school entry and performance IQ

in middle-primary school years (β = −.001, 95% CI: −.001, .000). Similarly, there was

a signicant indirect eect from ELCE to end of primary school literacy outcomes via

literacy at school entry and decoding skills in middle-primary school (β = .036, 95% CI:

.029, .044), but not for social adjustment at school entry and decoding skills in middle-

primary school years (β = −.003, 95% CI: −.005, .000).

Discussion

The ndings from the present study shed new light on pathways to literacy outcomes at

the end of primary school. We rst discuss the direct inuence of the early factors

measured (early SES and ELCE) before going on to explore the implications of the various

direct and indirect inuences on academic achievement in reading and writing.

Notably, this study illustrates the direct, enduring and wide-ranging inuence of

socioeconomic factors present in early life. Signicant, direct paths from early SES to all

predictor variables and to the academic outcome measure were observed. This comple

-

ments the ndings of Law et al. (2019), who reported similar SES eects on language

development at age 2 years in the ALSPAC dataset; we now provide evidence of such

eects extending into later childhood. The present results extend previous ndings to

demonstrate that early SES inuences upon literacy outcomes remain even when

a number of other factors are taken into consideration: social adjustment and literacy

skills at age 5 years, and PIQ, decoding skills, and language development and social

development aged 7–9 years and literacy outcomes aged 11 years.

Furthermore, this study conrms that the quality of the ELCE is inuential over and

above early SES eects. This adds to mounting evidence that quality of ELCE makes

a dierence even in otherwise adverse circumstances. To give some examples, mitigating

eects of higher quality ELCE have been reported for early language development (Law

et al., 2019), early cognitive development (Melhuish, 2010; Melhuish et al., 2008), and even

on academic achievement at GCSE and A level (Sammons et al., 2018). Our ndings are

also congruent with research beyond the UK, including studies from Australia, Germany

and USA. For example, Rodriguez and colleagues found both early learning environment

and SES eects on school readiness (Rodriguez & Tamis-Lemonda, 2011), while other

studies have emphasised the role of early communication and literacy activities with

caregivers in inuencing school readiness in literacy (Aikens & Barbarin, 2008; Neuman

et al., 2018; Niklas & Schneider, 2013; Niklas et al., 2015). In the present study, we see that

OXFORD REVIEW OF EDUCATION 273

direct eects of ELCE extend to school readiness in literacy and social domains aged

5 years, and beyond, to inuence oral language skills and social development in middle-

primary school (ages 7–9 years).

Interestingly, and unlike the ndings for early SES, there was no direct path from ELCE

to the end of primary school outcomes measure. Instead, the inuence is indirect, with

signicant routes via literacy at school entry, and, oral language skills and social ability at

the middle-primary school time point. At school entry, the literacy measure, based on an

assessment of reading and writing skills, was found to be much more inuential upon

literacy achievement at the end of primary school than the school-entry social adjustment

variable. This nding is consistent with the meta-analysis by Duncan and colleagues

(Duncan et al., 2007) but not with the later reanalysis of the Canadian data, as discussed

in the Introduction (Romano et al., 2010). The present study elucidates this issue by

revealing that it is slightly later in development (aged 7–9 years) when social skills

begin to impact signicantly on end of primary school literacy outcomes, in that this

can explain unique variance in outcomes. This ts with the general developmental pattern

that peer-based, social learning is a sophisticated skill that develops throughout middle

childhood and into adolescence (Baines & Howe, 2010; Howe, 2009; Mercer & Howe,

2012). It may be the case that, once the basic building blocks of reading and writing skills

are in place, children are better able to take advantage of their developing social

competence for the purposes of academic learning. For example, a child with secure

comprehension of a text may be more condent and able to discuss it with her peers,

a level of social interaction which then helps her to engage with new perspectives and

refer back to the text as appropriate.

Concerning the question of the relative importance of social development vs language

development on the path to literacy outcomes, we found diering amounts of variance

explained by these variables. The results underscore the role that oral language develop

-

ment plays in supporting academic outcomes in the domain of literacy (Snow, 1991). Higher

oral language ability at 7–9 years was associated with better literacy outcomes at primary

school leaving age and was the nal step on an indirect pathway from ELCE to literacy

outcomes, via literacy and social adjustment at school entry, as well as being directly linked

to ELCE. These ndings bolster existing links in the literature connecting early vocabulary

skills to academic achievement (Bleses et al., 2016) and demonstrate that structural oral

language skills, (i.e., language development in areas such as syntax, morphology and

semantics), continue to be important throughout the primary school years. The magnitude

of the direct eects on the end of primary school literacy outcomes (from 7 to 9 years to

outcomes at 11 years) was stronger for oral language development compared to social

development. For indirect paths (ELCE->5 years->7-9 years-> literacy outcome at 11 years),

however, the eects were not found to be signicantly greater for oral language compe

-

tence than for social competence. This supports our hypothesis of dierential inuences of

social and linguistic factors.

School-entry social adjustment was associated with relatively weaker eects. Social

adjustment at age 5 was predictive of social development aged 7–9 years, and signicant

direct eects were also observed for later oral language development. Interestingly,

although no signicant indirect pathways from school-entry social adjustment were

found, at 7–9 years there was a signicant, direct pathway from social development to

literacy outcomes. Taken together with the ndings of mixed evidence for dierential

274 J. L. GIBSON ET AL.

pathways discussed above, we suggest these results show that both social and linguistic

domains of development should be given due consideration when supporting children’s

academic progress in the later primary school years.

Alongside the variables associated with the main research questions motivating the

present study we also included measures that have already been linked to literacy

outcomes: performance IQ and decoding skills (Castles et al., 2018; Tiu et al., 2003).

Findings from these measures support previous research, demonstrating that each of

these constructs explains variance in literacy outcomes. Importantly, the ndings

reported here add the information that ELCE has a direct inuence on decoding skills

in particular.

Strengths and limitations

The present study has many strengths, including the large sample size and, unusually for

a large cohort sample, direct measures of expressive and receptive language. There are

also some limitations and caveats to be considered. One issue is that the sample was less

ethnically and economically diverse than the UK population in general. This limits the

potential generalisability of the study and we recommend replication of eects in diverse

samples in the UK and beyond. Further, we did not have a measure of the home language

and communication environment during the primary school years, nor ongoing measures

of SES. These factors have been shown to be inuential beyond the early years, as family

circumstances can change for many reasons (Jeynes, 2002; Toth et al., 2020). In addition to

this, the sample size for the measurement of social adjustment at school entry was much

lower than that for literacy skills. Although the sample size for social adjustment was still

substantial, this should be noted in interpreting the results and it would be desirable to

address this issue in future research.

It is also a strength that this study contains measures of both structural language skills

and pragmatic language skills. However, we recognise that not all language researchers

would agree with the choice to include pragmatics as part of the social development

latent variable rather than creating a generic linguistic variable. We made this decision

a priori, taking a broad view of pragmatics as the act of putting language to use in social

situations, in line with other studies that have made this distinction (Law et al., 2015; Law

et al., 2014). To account for the inevitable dependence between the two, we allowed our

measures of language development and social development to co-vary.

Finally, as we did not have access to objective test data to measure skills at school

entry, we cannot assess teacher report measures for accuracy. Nevertheless, the school

entry measures do behave as expected in the model and are associated with later

outcomes in the predicted fashion.

Implications for policy and practice

The ndings have implications for policy and practice in early childhood and in education.

Firstly, the ndings underscore the importance of policy responses to poor achievement

in reading and writing that address distal social causes, alongside those that might focus

on proximal environments or individual skills. Improving early family SES indicators such

as education and income would likely have a direct impact on child outcomes throughout

OXFORD REVIEW OF EDUCATION 275

primary schools. Further, as positive ELCE was observed to have an inuence on later skills

and outcomes even in the presence of early SES challenges, the present results provide

yet additional support for the importance of early childhood interventions (Law et al.,

2019; Melhuish, 2010; Sammons et al., 2004).

The lack of direct paths from the ELCE to literacy outcomes at the end of primary school

illuminates that there are other possible routes to supporting academic development in

those children who did not have optimal early learning experiences. There are implica

-

tions for the timing and targets for interventions during the middle childhood period.

At school entry, the ndings point to greater likely benets for literacy outcomes from

targeting early literacy skills, rather than social skills. Our ndings also underscore the

important role of decoding skills in literacy achievement (cf. Castles et al., 2018) and

therefore we advocate that this should be a continued aspect of policy approaches to

improving literacy outcomes.

Nevertheless, our ndings show that social school readiness inuences social and

linguistic factors in the mid-primary school years and that these are in turn associated

with improved literacy outcomes. Hence, there are good grounds for maintaining and

strengthening educational strategies that combine both linguistic and social elements in

order to support those students at risk of poor outcomes. Social interventions may not

‘pay o’ immediately in terms of literacy but aord a developmental context that can be

drawn upon increasingly as the child’s reading and writing skills advance.

Finally, we note that the social domain of development found to be signicant for literacy

outcomes in the present study may provide concrete and enjoyable intervention targets for

7–9 year olds. For example, educators could consider providing opportunities for practice of

pragmatic language skills and social skills via supported collaboration and conversational

engagement in classroom activities and in play and games with peers. This aligns with

recent studies demonstrating the success of dialogic teaching strategies that take a social-

constructivist approach to using talk in groups to promote learning (Mercer & Howe, 2012).

The present study demonstrates the importance of the early language and commu-

nication environment in supporting development of the skills that underpin children’s

achievement in reading and writing. Oral language comprehension and expression are

important predictors of variance in literacy outcomes, while social competences, includ

-

ing pragmatics, prosociality and social play, also play an important role and should

continue to receive attention in the mid-primary school years.

Acknowledgments

We are extremely grateful to all the families who took part in this study, the midwives for their

help in recruiting them, and the whole ALSPAC team, which includes interviewers, computer and

laboratory technicians, clerical workers, research scientists, volunteers, managers, receptionists

and nurses. We would also like to acknowledge the contributions of Peter Clough, Witold Orlik,

and Ciara Broomeld. The U.K. Medical Research Council and Wellcome (Grant 102215/2/13/2)

and the University of Bristol provide core support for the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and

Children (ALSPAC). This publication is the work of the authors Gibson, Newbury, Durkin, Pickles,

Conti-Ramsden, and Toseeb who will serve as guarantors for the contents of this article.

A comprehensive list of grant funding is available on the ALSPAC website (http://www.bristol.

ac.uk/alspac/external/documents/grant-acknowledgements.pdf). The analysis undertaken in this

article was specically funded by the Economic and Social Research Council (Grants ES/P001955/1

276 J. L. GIBSON ET AL.

and ES/P001955/2). G. C.-R. is supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR)

Manchester. A. P. is partially supported by NIHR NF-SI-0617-10120 and the Biomedical Research

Centre at South London and Maudsley National Health Service Foundation Trust and King’s

College London. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of

the National Health Service, the NIHR, or the Department of Health and Social Care. J. G. is

partially supported by the LEGO Foundation and by the Arts and Humanities Research Council

(Grant AH/N004671/1).

Disclosure statement

No potential conict of interest was reported by the authors.

Funding

This Arts and Humanities Research Council [AH/N004671/1] was supported by the Economic and

Social Research Council [ES/P001955/1 and ES/P001955/2]; Medical Research Council [102215/2/13/

2]; National Institute for Health Research [NF-SI-0617-10120]; LEGO Foundation; Wellcome Trust

[102215/2/13/2]; Arts and Humanities Research Council [AH/N004671/1].

Notes on contributors

Jenny Gibson is a Senior Lecturer in Psychology and Education at the University of Cambridge. She

is also a qualied speech and language therapist. Jenny’s research interests lie in the interplay

between linguistic and social development from childhood through to adolescence.

Dianne Newbury is a Reader in Medical Genetics and Genomics at Oxford Brookes University.

Dianne’s research centres around genetic contributions to speech, language and communication

disorders.

Kevin Durkin is Research Professor of Psychology at the University of Strathclyde. Kevin specialises

in social and communicative development.

Andrew Pickles is a Professor of Biostatistics and Psychological Methods at Kings College London.

Andrew’s research interests lie in the developing and applying statistical methods to mental health

and neurodevelopmental data.

Gina Conti-Ramsden is Emeritus Professor of Child Language and Learning at the University of

Manchester. Gina’s research focusses on the development of children and young people with

developmental language disorder and the associated strengths and diculties.

Umar Toseeb is a Senior Lecturer in Psychology in Education at the University of York. Umar’s

research interests lie at the intersection of neurodevelopmental diversity and mental health during

childhood and adolescence.

ORCID

Jenny L. Gibson http://orcid.org/0000-0002-6172-6265

Dianne F. Newbury

http://orcid.org/0000-0002-9557-268X

Kevin Durkin http://orcid.org/0000-0002-6167-3407

Andrew Pickles

http://orcid.org/0000-0003-1283-0346

Gina Conti-Ramsden

http://orcid.org/0000-0003-0235-7209

Umar Toseeb

http://orcid.org/0000-0002-7536-2722

OXFORD REVIEW OF EDUCATION 277

References

Aikens, N. L., & Barbarin, O. (2008). Socioeconomic dierences in reading trajectories: The contribu-

tion of family, neighborhood, and school contexts. Journal of Educational Psychology, 100(2),

235–251. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.100.2.235

Baines, E., & Howe, C. (2010). Discourse topic management and discussion skills in middle childhood:

The eects of age and task. First Language, 30(3–4), 508–534. https://doi.org/10.1177/

0142723710370538

Bishop, D. V. M. (1998). Development of the Children’s communication checklist (CCC): A method for

assessing qualitative aspects of communicative impairment in children. Journal of Child

Psychology and Psychiatry, 39(6), 879–891. https://doi.org/10.1111/1469-7610.00388

Bishop, D. V. M., & Snowling, M. J. (2004). Developmental dyslexia and specic language impairment:

Same or dierent? Psychological Bulletin, 130(6), 858–886. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.130.

6.858

Blair, C., & Cybele Raver, C. (2015). School readiness and self-regulation: A developmental psycho-

biological approach. Annual Review of Psychology, 66(1), 711–731. https://doi.org/10.1146/

annurev-psych-010814-015221

Bleses, D., Makransky, G., Dale, P. S., Højen, A., & Ari, B. A. (2016). Early productive vocabulary predicts

academic achievement 10 years later. Applied Psycholinguistics, 37(6), 1461–1476. https://doi.org/

10.1017/S0142716416000060

Bowyer-Crane, C., Snowling, M. J., Du, F. J., Fieldsend, E., Carroll, J. M., Miles, J., Götz, K., & Hulme, C.

(2008). Improving early language and literacy skills: Dierential eects of an oral language versus

a phonology with reading intervention. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 49(4), 422–432.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01849.x

Boyd, A., Golding, J., Macleod, J., Lawlor, D. A., Fraser, A., Henderson, J., Molloy, L., Ness, A., Ring, S., &

Smith, G. D. (2013). Cohort prole: The ‘children of the 90s’—the index ospring of the avon

longitudinal study of parents and children. International Journal of Epidemiology, 42(1), 111–127.

https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dys064

Bradley, R. H., & Corwyn, R. F. (2002). Socioeconomic status and child development. Annual Review of

Psychology, 53(1), 371–399. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135233

Carlton, M. P., & Winsler, A. (1999). School readiness: The need for a paradigm shift. School

psychology review, 28(3), 338–352. https://doi.org/10.1080/02796015.1999.12085969

Carpenter, M., Nagell, K., Tomasello, M., Butterworth, G., & Moore, C. (1998). Social Cognition, joint

attention, and communicative competence from 9 to 15 months of age. Monographs of the

Society for Research in Child Development, 63(4), i. https://doi.org/10.2307/1166214

Castles, A., Rastle, K., & Nation, K. (2018). Ending the reading wars: Reading acquisition From novice

to expert. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 19(1), 5–51. https://doi.org/10.1177/

1529100618772271

Denham, S. A. (2006). Social-emotional competence as support for school readiness: What is it and

how do we assess it? Early Education and Development, 17(1), 57–89. https://doi.org/10.1207/

s15566935eed1701_4

Denham, S. A., & Brown, C. (2010). “Plays nice with others”: Social–emotional learning and academic

success. Early Education and Development, 21(5), 652–680. https://doi.org/10.1080/10409289.

2010.497450

Duncan, G. J., Dowsett, C. J., Claessens, A., Magnuson, K., Huston, A. C., Klebanov, P., Pagani, L. S.,

Feinstein, L., Engel, M., Brooks-Gunn, J., Sexton, H., Duckworth, K., & Japel, C. (2007). School

readiness and later achievement. Developmental Psychology, 43(6), 1428–1446. https://doi.org/10.

1037/0012-1649.43.6.1428

Durkin, K., Simkin, Z., Knox, E., & Conti-Ramsden, G. (2009). Specic language impairment and school

outcomes. II: Educational context, student satisfaction, and post-compulsory progress.

International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 44(1), 36–55. https://doi.org/10.

1080/13682820801921510

Feinstein, L. (2003). Inequality in the early cognitive development of British children in the 1970

cohort. Economica, 70(277), 73–97. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0335.t01-1-00272

278 J. L. GIBSON ET AL.

Fink, E., Browne, W. V., Hughes, C., & Gibson, J. L. (2019). Using a “child’s-eye view” of social success

to understand the importance of school readiness at the transition to formal schooling. Social

Development, 28, 186–199. https://doi.org/10.1111/sode.12323

Fraser, A., Macdonald-Wallis, C., Tilling, K., Boyd, A., Golding, J., Smith, G. D., Henderson, J.,

Macleod, J., Molloy, L., Ness, A., Ring, S., Nelson, S. M., & Lawlor, D. A. (2013). Cohort prole: The

Avon longitudinal study of parents and children: ALSPAC mothers cohort. International Journal of

Epidemiology, 42(1), 97–110. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dys066

Fujiki, M., Brinton, B., Hart, C. H., & Fitzgerald, A. H. (1999). Peer acceptance and friendship in children

with specic language impairment. Topics in Language Disorders, 19(2), 34–48. https://doi.org/10.

1097/00011363-199902000-00005

Goodman, R. (1997). The strengths and diculties questionnaire: A research note. Journal of Child

Psychology and Psychiatry, 38(5), 581–586. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.1997.tb01545.x

Ho, E. (2003). Causes and consequences of SES-related dierences in parent-to-child speech. In M.

H. Bornstein & R. H. Bradley (Eds.), Monographs in parenting series. Socioeconomic status, parenting,

and child development (p. 147–160). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers

Ho, E. (2006). How social contexts support and shape language development. Developmental

Review, 26(1), 55–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2005.11.002

Howe, C. (2009). Peer groups and children’s development. Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1002/

9781444318098

Hoyte, F., Torr, J., & Degotardi, S. (2014). The language of friendship: Genre in the conversations of

preschool children. Journal of Early Childhood Research, 12(1), 20–34. https://doi.org/10.1177/

1476718X13492941

Huttenlocher, J., Waterfall, H., Vasilyeva, M., Vevea, J., & Hedges, L. V. (2010). Sources of variability in

children’s language growth. Cognitive Psychology, 61(4), 343–365. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cogp

sych.2010.08.002

Jerrim, J., Vignoles, A., Lingam, R., & Friend, A. (2015). The socio-economic gradient in children’s

reading skills and the role of genetics. British Educational Research Journal, 41(1), 6–29. https://doi.

org/10.1002/berj.3143

Jeynes, W. H. (2002). The challenge of controlling for SES in social science and education research.

Educational Psychology Review, 14(2), 205–221. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1023/

A:1014678822410

Konold, T. R., & Pianta, R. C. (2005). Empirically-derived, person-oriented patterns of school readiness

in typically-developing children: Description and prediction to rst-grade achievement. Applied

Developmental Science, 9(4), 174–187. https://doi.org/10.1207/s1532480xads0904_1

Law, J., Clegg, J., Rush, R., Roulstone, S., & Peters, T. J. (2019). Association of proximal elements of

social disadvantage with children’s language development at 2 years: An analysis of data from

the children in focus (CiF) sample from the ALSPAC birth cohort. International Journal of Language

and Communication Disorders, 54(3), 362–376. https://doi.org/10.1111/1460-6984.12442

Law, J., Rush, R., Clegg, J., Peters, T., & Roulstone, S. (2015). The role of pragmatics in mediating the

relationship between social disadvantage and adolescent behavior. Journal of Developmental and

Behavioral Pediatrics, 36(5), 389–398. https://doi.org/10.1097/DBP.0000000000000180

Law, J., Rush, R., & McBean, K. (2014). The relative roles played by structural and pragmatic language

skills in relation to behaviour in a population of primary school children from socially disadvan-

taged backgrounds. Emotional and Behavioural Diculties, 19(1), 28–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/

13632752.2013.854960

MacKinnon, D. P. (2000). Equivalence of the mediation, confounding and suppression eect.

Prevention Science, 1(4), 173–181. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1026595011371

Melhuish, E. (2010). Impact of the home learning environment on child cognitive development:

Secondary analysis of data from “growing up in Scotland”. Scottish Government. https://www.nls.

uk/scotgov/2010/impactofthehomelearningenvironment.pdf

Melhuish, E., Phan, M. B., Sylva, K., Sammons, P., Siraj-Blatchford, I., & Taggart, B. (2008). Eects of the

home learning environment and preschool center experience upon literacy and numeracy

development in early primary school. Journal of Social Issues, 64(1), 95–114. https://doi.org/10.

1111/j.1540-4560.2008.00550.x

OXFORD REVIEW OF EDUCATION 279

Mercer, N., & Howe, C. (2012). Explaining the dialogic processes of teaching and learning: The value

and potential of sociocultural theory. Learning, Culture and Social Interaction, 1(1), 12–21. https://

doi.org/10.1016/j.lcsi.2012.03.001

Mok, P. L. H., Pickles, A., Durkin, K., & Conti-Ramsden, G. (2014). Longitudinal trajectories of peer

relations in children with specic language impairment. Journal of Child Psychology and

Psychiatry, 55(5), 516–527. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12190

Muthen, L. K., & Muthen, B. O. (2012). Mplus User’s Guide (7th ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Muthén &

Muthén.

Neuman, S. B., Kaefer, T., & Pinkham, A. M. (2018). A double dose of disadvantage: Language

experiences for low-income children in home and school. Journal of Educational Psychology,

110(1), 102–118. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000201

Niklas, F., & Schneider, W. (2013). Home literacy environment and the beginning of reading and

spelling. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 38(1), 40–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.

2012.10.001

Niklas, F., Tayler, C., & Schneider, W. (2015). Home-based literacy activities and children’s cognitive

outcomes: A comparison between Australia and Germany. International Journal of Educational

Research, 71, 75–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2015.04.001

Nunes, T., Bryant, P., & Olsson, J. (2003). Learning Morphological and Phonological Spelling Rules: An

Intervention Study. Scientic Studies of Reading, 7(3), 289–307. doi:10.1207/S1532799XSSR0703_6

Rakoczy, H., Tomasello, M., & Striano, T. (2006). The role of experience and discourse in children’s

developing understanding of pretend play actions. British Journal of Developmental Psychology,

24(2), 305–335. https://doi.org/10.1348/026151005X36001

Rodriguez, E. T., & Tamis-Lemonda, C. S. (2011). Trajectories of the home learning environment

across the rst 5 years: Associations with children’s vocabulary and literacy skills at

Prekindergarten. Child Development, 82(4), 1058–1075. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.

2011.01614.x

Romano, E., Babchishin, L., Pagani, L. S., & Kohen, D. (2010). School readiness and later achievement:

Replication and extension using a nationwide Canadian survey.. Developmental Psychology, 46(5),

995–1007. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018880

Romeo, R. R., Leonard, J. A., Robinson, S. T., West, M. R., Mackey, A. P., Rowe, M. L., & Gabrieli, J. D. E.

(2018). Beyond the 30-million-word gap: Children’s conversational exposure is associated with

language-related brain function. Psychological Science, 29(5), 700–710. https://doi.org/10.1177/

0956797617742725

Rose, E., Lehrl, S., Ebert, S., & Weinert, S. (2018). Long-term relations between children’s

language, the home literacy environment, and socioemotional development from ages 3 to

8. Early Education and Development, 29(3), 342–356. https://doi.org/10.1080/10409289.2017.

1409096

Roulstone, S., Law, J., Rush, R., Clegg, J., & Peters, T. (2011). Investigating the role of language in

children’s early educational outcomes. In Research Report DFE-RR134. Department for Education.

https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_

-

data/le/181549/DFE-RR134.pdf doi:10.1037/e603062011-001

Rust, J. (1996). The manual of the wechsler objective language dimensions (WOLD) UK edition. The

Psychological Corporation.

Sammons, P., Elliot, K., Sylva, K., Melhuish, E., Siraj-Blatchford, I., & Taggart, B. (2004). The impact of

pre-school on young children’s cognitive attainments at entry to reception. British Educational

Research Journal, 30(5), 691–712. https://doi.org/10.1080/0141192042000234656

Sammons, P., Toth, K., & Sylva, K. (2018). The drivers of academic success for ‘bright’ but disadvan-

taged students: A longitudinal study of AS and A-level outcomes in England. Studies in

Educational Evaluation, 57, 31–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stueduc.2017.10.004

Snow, C. E. (1991). The theoretical basis for relationships between language and literacy in

development. Journal of Research in Childhood Education, 6(1), 5–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/

02568549109594817

280 J. L. GIBSON ET AL.

Snow, K. L. (2006). Measuring school readiness: Conceptual and practical considerations. Early

Education and Development, 17(1), 7–41. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc. https://doi.org/10.

1207/s15566935eed1701_2

Son, S.-H., & Morrison, F. J. (2010). The nature and impact of changes in home learning environment

on development of language and academic skills in preschool children.. Developmental

Psychology, 46(5), 1103–1118. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020065

St Clair, M. C., Croudace, T., Dunn, V. J., Jones, P. B., Herbert, J., & Goodyer, I. M. (2015). Childhood

adversity subtypes and depressive symptoms in early and late adolescence. Development and

Psychopathology, 27(3), 885–899. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0954579414000625

St Clair, M. C., Pickles, A., Durkin, K., & Conti-Ramsden, G. (2011). A longitudinal study of behavioral,

emotional and social diculties in individuals with a history of specic language impairment (SLI).

Journal of Communication Disorders, 44(2), 186–199. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcomdis.2010.09.004

StataCorp. (2019). Stata statistical software: Release 16. Texas: College Station.

Taylor, L. C., Clayton, J. D., & Rowley, S. J. (2004). Academic socialization: Understanding parental

inuences on children’s school-related development in the early years. Review of General

Psychology, 8(3), 163–178. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.8.3.163

Tiu, R. D., Thompson, L. A., & Lewis, B. A. (2003). The role of IQ in a component model of reading.

Journal of Learning Disabilities, 36(5), 424–436. https://doi.org/10.1177/00222194030360050401

Toth, K., Sammons, P., Sylva, K., Melhuish, E., Siraj, I., & Taggart, B. (2020). Home learning environ-

ment across time: the role of early years HLE and background in predicting HLE at later ages.

School Eectiveness and School Improvement, 31(1), 7–30. doi:10.1080/09243453.2019.1618348

Von Salisch, M., Haenel, M., & Denham, S. A. (2015). Self-regulation, language skills, and emotion

knowledge in young children from northern Germany. Early Education and Development, 26(5–6),

792–806. https://doi.org/10.1080/10409289.2015.994465

Vrikki, M., Wheatley, L., Howe, C., Hennessy, S., & Mercer, N. (2019). Dialogic practices in primary

school classrooms. Language and Education, 33(1), 85–100. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500782.

2018.1509988

Wechsler, D. (1991). The Wechsler intelligence scale for children (3rd ed.). San Antonio, TX: The

Psychological Corporation.

Appendix. Early language and communication environment (ELCE)

When the child was aged 18–24 months, the mother was asked about the child’s early language and

communication environment. These questions were previously coded by Roulstone et al. (2011) and