www.peoplelab.hks.harvard.edu | 1

In collaboration with the California Policy Lab, the Los Angeles Mayor’s Ofce Innovation Team, and

the Los Angeles Economics Workforce and Development Department (EWDD), we conducted a

randomized experiment to test the impact of timely, actionable, and behaviorally informed text

messages aimed at increasing job seekers’ engagement with the city’s workforce development services.

In a 14-week intervention, job seekers received text messages reminding them to engage in job-

search related activities, utilize EWDD WorkSource Center resources, and set goals related to securing

employment. We then measured the effect of the text message campaign on engagement with Los

Angeles WorkSource Centers and subsequent employment outcomes.

INCREASING ENGAGEMENT &

EMPLOYMENT OUTCOMES IN

WORKFORCE DEVELOPMENT

PROGRAMS

Jessica Lasky-Fink, Elizabeth Linos, and Laura Schwartz

April 2024

KEY TAKEAWAYS

1

3

Clients who received

timely and behaviorally

informed text messages

were 3% more likely to

engage with Los Angeles

WorkSource Centers than

those who did not receive

communications.

Clients who received

text messages were 20%

more likely to secure

employment at the end

of the study compared to

those who did not receive

text messages.

A majority of clients who

received text messages

found them helpful and

expressed interest in

continuing to receive

similar messages in

the future.

2

CONTEXT

Unemployment and underemployment are strongly correlated with

poverty and have been shown to negatively affect psychological

well-being.

1

Many cities and states offer free employment services for

residents. However, these resources are only effective if they are used.

Los Angeles EWDD runs 16 WorkSource Centers (WSCs) that provide

free employment services to around 27,000 job seekers a year in

LA County. WorkSource Centers offer specialized services including

career counseling, skills workshops, resume guidance, job matching,

and employment referrals to enrolled clients. However, despite

this robust workforce development infrastructure, the WorkSource

Centers are underutilized by Los Angeles residents looking for

employment. In fact, over half of enrolled clients (56%) only visit their

local WorkSource Center once after enrolling.

Motivating sustained engagement over time is a common challenge

faced by many public sector agencies. While people often intend to

change and maintain their behavior, evidence suggests that doing

so is difcult. For instance, WorkSource Center clients may intend to

apply for a certain number of jobs each week. But, job seekers—like

most people—face numerous cognitive and psychological barriers

that can make it difcult to remember and motivate themselves to

follow through on their intentions. This intention–behavior gap may

contribute to low rates of client engagement with the WorkSource

Centers, as well as limited employment outcomes.

www.peoplelab.hks.harvard.edu | 2

RESEARCH

For 14 weeks from November 2019 to February 2020, we conducted a randomized experiment with 5,537

active WorkSource Center clients. Clients were randomly assigned to a control group that did not receive

communication as part of the study, or one of two treatment groups:

Reminders: Clients received weekly text messages with information about upcoming WSC events

and workshops, and reminders to engage in individual job-search activities like checking in with

case managers and utilizing the WSC computer centers.

Reminders + Plan-making: Clients received the same weekly text message reminders as the

“Reminders” group with additional language encouraging goal-setting and links to online plan-

making forms. These messages leveraged evidence showing that prompting people to set goals

and make plans can increase follow-through and help bridge the intention–behavior gap in areas

like voting and annual u shots.

At the end of the 14-week intervention, we evaluated the impact of receiving communications on

employment outcomes and individuals’ engagement with WorkSource Centers. Engagement was

measured as any interaction with a WorkSource Center including meeting with a case manager or

attending a workshop or recruitment event. Additionally, we measured whether clients were employed

in March 2020—approximately six weeks after the end of the intervention. Employment was captured in

EWDD administrative data.

A second cohort was planned for January–March 2020 but was cut short due to the outbreak of the

Covid-19 pandemic. This cohort is thus excluded from this analysis.

FIGURE 1

Sample text messages

sent to clients in the

Reminders and Reminders +

Plan-making groups

1

2

1 2

Reminders Reminders + Plan-making

www.peoplelab.hks.harvard.edu | 3

WHAT WE FOUND

To evaluate the impact of the text message campaign, we compared outcomes between clients who

were assigned to the no-communication control group and those who were assigned to either treatment

group. We found that clients who were assigned to receive any communication (Reminders or Reminders

+ Plan-making) were 3% more likely to interact with the WorkSource Centers: 45.9% of clients in the two

treatment groups interacted one or more times with the WSCs during the 14-week intervention period

compared to 44.5% of clients in the no-communication control group.

Additionally, clients who were assigned to receive text messages were 20% more likely to be employed

approximately six weeks after the intervention period: 9.4% of clients in the two treatment conditions were

employed according to EWDD administrative data, compared to 7.8% of clients in the control group.

At the end of the intervention, we also conducted a follow-up text message survey among all clients in

the experiment. Of 212 clients who were assigned to one of the treatment groups and responded to the

survey, 75% remembered receiving the text messages. Of these, 80% reported nding the text messages

helpful, and 82% reported being interested in enrolling in a similar program if offered in the future.

Because the second cohort was cut short, we are underpowered to detect effects between the two

treatment groups on any outcomes of interest.

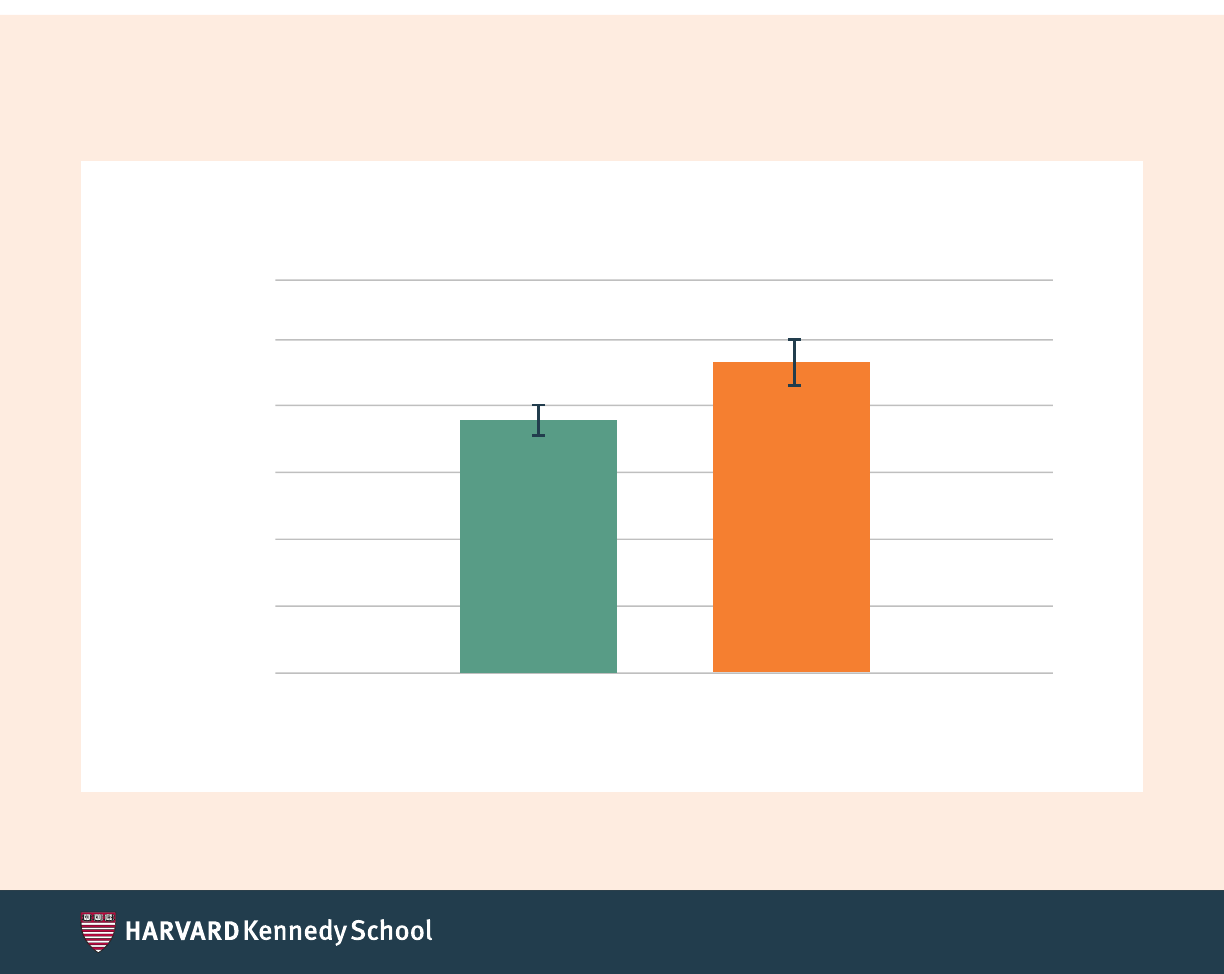

FIGURE 2

Employment at the end of the 14-week intervention.

(total N=5,537)

0.0%

2.0%

4.0%

6.0%

8.0%

10.0%

12.0%

% employed

Treatment group

Control

7.8%

Pooled treatment

9.4%

About The People Lab

The People Lab aims to empower the public sector by producing cutting-

edge research on the people of government and the communities they

serve. Using evidence from public management and insights from

behavioral science, we study, design, and test strategies for solving

urgent public sector challenges in three core areas: strengthening the

government workforce; improving resident–government interactions;

and reimagining the production and use of evidence.

Contact Us

[email protected]d.edu

@HKS_PeopleLab

WHAT’S NEXT

A 14-week program of weekly personalized communications increased client engagement with

WorkSource Centers and improved employment outcomes. Additionally, approximately 80% of

jobseekers who received the communications reported nding them helpful and expressed interest

in enrolling in the program if offered again. These ndings suggest that job seekers may benet from

low-cost communications to prompt engagement with workforce development services and job-

search–related activities. Future research could consider similar information interventions in other

public sector contexts that require sustained behavior and engagement over time.

SOURCE

1. Theodossiou, I. (1988). The effects of low-pay and unemployment on psychological well-being: A logistic regression

approach, Journal of Health Economics 17(1), 85-104. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0167-6296(97)00018-0