Initial Report on Public Health

August 2009

Public Health Division

Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care

Initial Report on Public Health Contacts

Public Health Practice Branch:

iii

We are very pleased to provide you with the Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care’s (MOHLTC)

Initial Report on Public Health in Ontario.

The Public Health Division, in partnership with the Ministry of Health Promotion (MHP) and

the Ministry of Children and Youth Services (MCYS), has made significant strides to renew

public health in Ontario and build a public health sector with a greater focus on performance,

accountability and sustainability. Some of our recent achievements towards this goal include

delivering the new Ontario Public Health Standards, producing the Ontario Health Plan for

an Influenza Pandemic, and now, releasing a public report that reflects the state of public

health in Ontario. This report demonstrates our commitment to a public health sector that

is accountable to the people of Ontario.

The indicators provided in this report are intended to contribute to our understanding of

public health in Ontario as a system, at both the provincial and local levels. As we move

towards implementing a performance management system in public health, we have an

increased need for information that can be used to ensure the public’s health is protected, to

inform decisions on where improvements are required, to ensure that appropriate governance

is in place and to help promote organizational excellence.

This initial report is intended to provide a snapshot of the current state of public health in

Ontario. Over time, with the continued involvement of public health professionals in the

sector, different indicators will need to be identified and developed. There is significant

expertise related to performance management already available within our sector, and within

the health care sector, and we will be relying on these resources to assist in developing

the tools and processes required to operate a useful, efficient and effective performance

management system at the provincial level.

Foreword

iv

The work of the Capacity Review Committee (2006) gave us an important conceptual framework for

performance management. The work to implement this vision is now well underway, and this report is

the first tangible product that begins to articulate that vision.

We hope you find the report informative and, most importantly, useful. We would like to take this opportunity

to thank the members of the Performance Management Working Group who provided advice that shaped the

development of this report. Their knowledge and wisdom have contributed substantially to the quality of this

product.

Allison J. Stuart Arlene S. King, MD, MHSc, FRCPC

Assistant Deputy Minister (A) Chief Medical Officer of Health (effective June 15, 2009)

Public Health Division

Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care

David C. Williams MD, MHSc, FRCPC

Chief Medical Officer of Health (A) (until June 15, 2009)

Associate Chief Medical Officer of Health,

Health Protection

v

Initial Report on Public Health 2009

Producing this report involved the commitment of a diverse group of individuals, each of whom contributed

their time and advice to ensure that the final product was representative of public health in Ontario at both

the local and provincial levels. The ministry acknowledges and thanks the many individuals who contributed

to this report including:

• ThemembersofthePerformanceManagementWorkingGroup(PMWG)in2007-2008

i

who advised on the

development of this report:

– Dr. Kathleen Dooling, Community Medicine Resident, University of Toronto

– Dr. Vera Etches, Medical Officer of Health (A), Sudbury & District Health Unit

– Dr. Charles Gardner, Medical Officer of Health,

Simcoe-MuskokaDistrictHealthUnit/2007-08COMOHChair

– Ms. Dawne Kamino, Director, Controllership & Resources Management Branch,

Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care

– Dr. Jeff Kwong, Scientist, Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences

– Dr. Robert Kyle, Commissioner & Medical Officer of Health, Durham Region Health Department

– Dr. Jack Lee, Senior Strategic Advisor, Ministry of Health Promotion

– Dr. Doug Manuel, Senior Scientist, Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences

(co-chairDecember,2007–May,2008)

– Dr. Rosana Pellizzari, Associate Medical Officer of Health, Toronto Public Health

(co-chairfromMay,2008)

– Ms. Katharine Robertson-Palmer, Coordinator, Education and Research, Ottawa Public Health

– Ms. Julie Stratton, Manager, Epidemiology, Peel Regional Health Unit/APHEO

– Ms. Brenda Tipper, Health System Strategy Division, Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care

– Ms. Monika Turner, Director, Public Health Standards Branch,

Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care (co-chair)

– Dr. Erica Weir, Associate Medical Officer of Health, York Regional Health Unit

– Ms. Jackie Wood, Manager, Corporate Services, Ministry of Health Promotion

• Staffinpublichealthunitsacrosstheprovince,whocontributedbycompletingthesurveyofboards

of health on governance and management issues, providing case studies, and verifying the indicator

methodology and data that appear in the report.

• MembersoftheAssociationofPublicHealthBusinessAdministratorswhoassistedindevelopingthe

survey tool that was used to gather governance, organizational practices and financial data.

Acknowledgements

i

It should be noted that some members changed positions during the course of the production of the report. However this list accurately

reflects the PMWG membership and roles during the period of the report’s development.

vi

• TheInstituteforClinicalEvaluativeSciences(ICES)andPeelPublicHealth,whichprovideddataanalysis

and advice.

• MembersoftheAssociationofPublicHealthEpidemiologistsinOntario(APHEO)whoprovidedtechnical

advice on indicator methodology and development:

– Ms. Deborah Carr

– Ms. Sherri Deamond

– Mr. Foyez Haque

– Ms. Joanna Oliver

– Ms. Suzanne Sinclair

• StaffwithintheMinistryofHealthPromotionandtheMinistryofChildrenandYouthServices,

who contributed to the indicator narratives and conducted data analysis.

• StaffwithintheMinistryofHealthandLong-TermCare,whoadvisedonthedevelopmentofthisreport

throughout2008-09withinthefollowingbranches:

ii

– Communications and Information Branch

– Controllership and Resources Management Branch

– Emergency Management Branch

– Environmental Health Branch

– Health Analytics Branch

– Infectious Diseases Branch

– Legal Services Branch

– Strategic Alignment Branch

• StaffoftheStrategicPolicyandImplementationBranch,

ii

who provided research and editorial support in

the development of this report:

– Ms. Allison McArthur

– Ms. Beata Pach

• StaffofthePublicHealthStandardsBranch,

ii

who acted as secretariat to the PMWG and guided this

document through the development process, including:

– Mr. David Moore

– Mr. Hassan Parvin

– Ms. Paulina Salamo

– Ms. Sylvia Shedden

– Ms. Joanne Thanos

– Ms. Lisa Vankay

– Ms. Tricia Willis

ii

Note that the Public Health Division underwent a restructuring that coincided with the publication of this report. The branch names

shown here reflect the branches as they were known during the period of the report’s development.

Acknowledgements

vii

Initial Report on Public Health 2009

Table of Contents

Foreword .............................................................................................................. iii

Acknowledgements ................................................................................................ v

Section I: Introduction ..........................................................................................1

Section II: Overview of the Public Health Sector ............................................... 3

Scope of Public Health ...................................................................................................... 3

Legislative Framework for Public Health ....................................................................... 4

Determinants of Health...................................................................................................... 5

Public Health Programs and Services in Ontario ........................................................... 6

Health Unit Profiles ............................................................................................................ 6

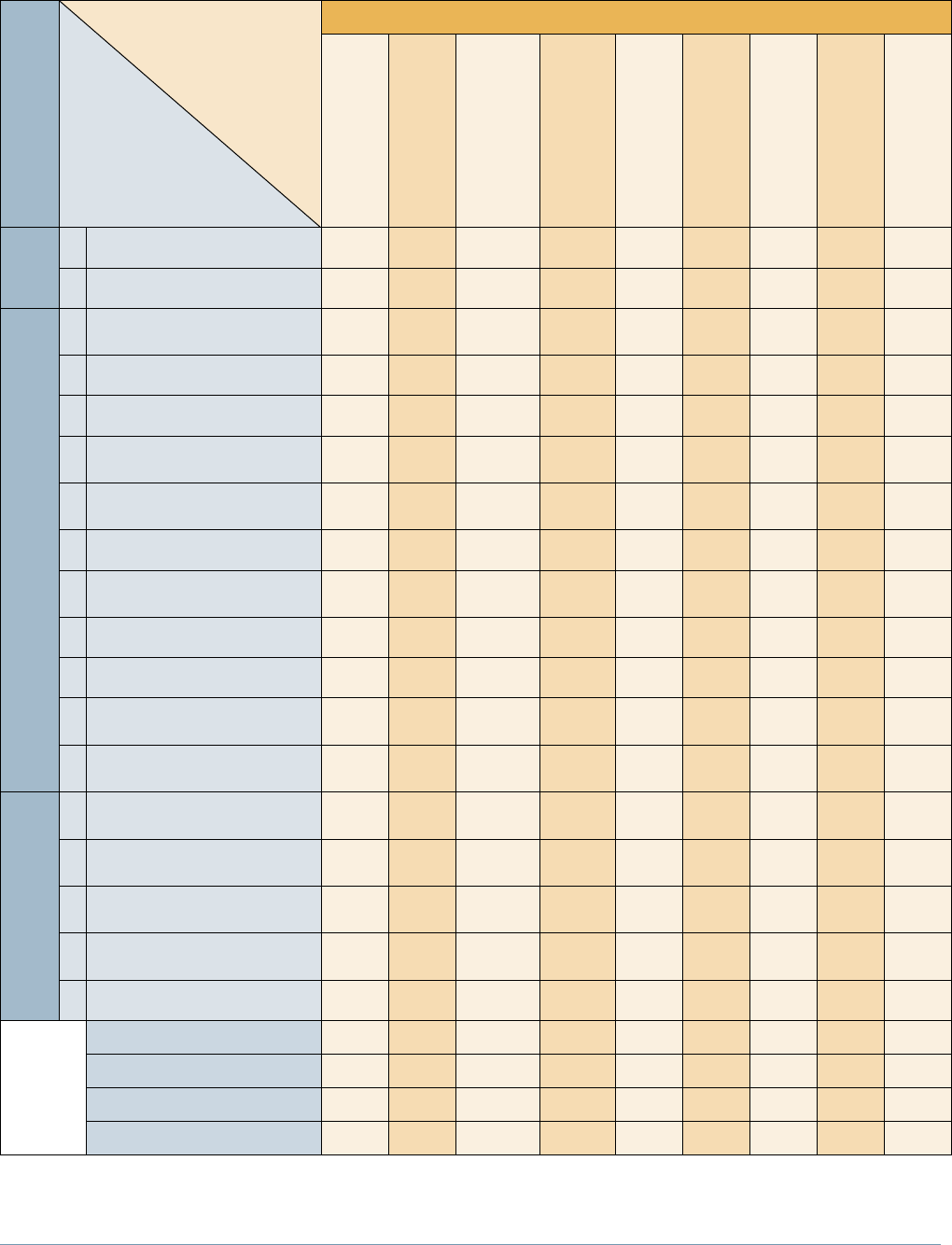

Table 1: Health Unit Profiles ............................................................................................. 8

Section III: Performance of the Public Health Sector ...................................... 13

Report Development ........................................................................................................ 13

Development of Indicators .............................................................................................. 15

Case Studies ...................................................................................................................... 16

Section IV: Indicators ..........................................................................................17

Table 2: Indicators by Public Health Unit ...................................................................... 20

Group A – Population Health Indicators............................................................29

1. Teen Pregnancy .......................................................................................................... 29

2. Low Birth Weight ........................................................................................................ 31

3. Breastfeeding Duration ............................................................................................. 32

4. Postpartum Contact ................................................................................................... 33

5. Smoking Prevalence .................................................................................................. 34

6. Youth Lifetime Smoking Abstinence ........................................................................ 34

7. Adult Heavy Drinking ................................................................................................ 37

8.YouthHeavyDrinking ................................................................................................ 39

9. Physical Activity Index .............................................................................................. 40

10. Healthy Body Mass Index .......................................................................................... 41

11. Fruit and Vegetable Consumption............................................................................ 42

12. Fall-Related Hospitalizations among Seniors ......................................................... 43

13. Enteric Illnesses Incidence ....................................................................................... 46

14. Respiratory Infection Outbreaks in Long-Term Care Homes ............................... 46

viii

15. Chlamydia Incidence ................................................................................................. 48

16. Immunization Coverage for Hepatitis B .................................................................. 48

17. Immunization Coverage for Measles, Mumps and Rubella ................................... 50

18.AdverseWaterQualityIncidents .............................................................................. 51

Group B – Governance and Accountability Indicators .....................................53

19. Total Board of Health Expenditures ........................................................................ 53

20. Board of Health Expenditure Variance ................................................................... 54

21. Expenditures on Training and Professional Development ................................... 56

22. Numbers of FTEs by Job Category .......................................................................... 56

23. Number of Vacant Positions by Job Category ........................................................ 58

24. Employment Status of Medical Officers of Health ................................................ 59

25. Staff Length of Service .............................................................................................. 61

26. Familiarity with Public Health Unit Programs and Services ................................ 62

27. Issuance of a Health Status Report .......................................................................... 63

28.StrategicPlan .............................................................................................................. 65

29. Emergency Response Plan Tested ........................................................................... 65

30. Accreditation Status .................................................................................................. 66

31. Medical Officer of Health Performance Evaluation .............................................. 67

32. Medical Officer of Health Reporting Relationships ............................................... 67

33. Board Member Orientation ....................................................................................... 68

34. Board Self-Evaluation ................................................................................................ 68

Section V: Moving Towards Performance Reporting ......................................... 71

Context for Performance Management in Public Health ........................................... 71

Developing a Performance Management Culture ........................................................ 73

Future Indicators .............................................................................................................. 73

Requirements for a Performance Management System ............................................. 74

Implementation Challenges ............................................................................................ 74

Implementation Opportunities ....................................................................................... 75

Conclusion ......................................................................................................................... 75

Appendices ........................................................................................................... 77

Appendix 1: Peer Groups ................................................................................................ 77

Appendix 2: Health Unit Profile Variable Definitions ................................................. 83

Appendix 3: Indicator Definitions ................................................................................. 89

References .......................................................................................................... 125

Table of Contents

1

Initial Report on Public Health 2009

Introduction

Section I:

In A Dictionary of Public Health, John Last

1

defines public health as:

“an organized activity of society to promote, protect, improve, and when necessary, restore the health of

individuals, specified groups, or the entire population ...The term “public health” can describe a concept,

a social institution, a set of scientific and professional disciplines and technologies, and a form of

practice ... It is a way of thinking, a set of disciplines, an institution of society, and a manner of practice”.

On a daily basis, Ontario’s public health sector contributes to keeping Ontarians healthy and safe through

health protection, disease prevention and management, and health promotion activities. The essential day-to-

day work of the public health sector often goes unnoticed as many potential health threats or conditions are

contained or averted by routine prevention, health protection, health promotion, as well as surveillance and

management activities carried out by public health organizations across Ontario.

Some of the great accomplishments of public health in the twentieth century include the virtual elimination

of polio in Canada, the pasteurization of milk, the disinfection and fluoridation of drinking water, and the

identification and prevention of tobacco-related illness. These examples demonstrate the contribution that

public health has made to protect the health of the population.

A strong public health sector is vital to a healthy and safe Ontario population and yet we tend not to think

about it except in times of crisis. The anonymity of the public health sector disappeared quickly with the

gastroenteritis outbreaks in Walkerton in 2000 and the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) crisis

in 2003. These two events revealed serious weaknesses in the province’s public health sector at the time.

Key reports that resulted from the Walkerton incident (the O’Connor Reports

2,3

) and SARS (the Walker,

4,5

Naylor,

6

and Campbell

7,8,9

reports) provided a range of recommendations for renewal of public health in

Canada and specifically in Ontario. In response, the government of Ontario announced Operation Health

Protection

10

in 2004. The Operation Health Protection (OHP) action plan focused on revitalizing the public

health sector, preventing future health threats, and promoting a healthy Ontario. The plan also included a

commitment to produce an annual Ontario public health performance report.

Ontario has made significant progress delivering on the commitments made in the OHP. Ontario’s continued

commitment to build a strong, flexible, and responsive public health sector has been demonstrated through

initiatives such as:

• amendingtheHealth Protection and Promotion Act (HPPA)

11

to modernize the legislation

• creatingtheOntarioAgencyforHealthProtectionandPromotion

• increasingprovincialfundingtopublichealthunits

• developingnewstandardsforpublichealth,whichstrengthenpublichealthsectoraccountability

Another outcome of OHP was the establishment of the Capacity Review Committee (CRC). The committee

was tasked with making recommendations to government on long-term strategies to revitalize public health

in Ontario. The committee delivered its final report in 2006, which included a recommendation to adopt a

comprehensive public health performance management system.

12

Public reporting was seen as an important

tool within this system to demonstrate accountability and measure performance.

2

Ontario has responded to the need to improve performance management in public health by initiating work

on the development of a public health performance management system. This system is intended to enable

the public health sector to demonstrate its achievements in terms of improvements in both outcomes and

services over time.

The introduction of the new performance management system is intended to move Ontario away from

focusing primarily on compliance with processes, towards an emphasis on tracking outcomes. As the

performance management system continues to be developed, improved measures of outcomes will follow.

This initial report provides a snapshot of Ontario’s public health sector. It provides an overview of the scope

of public health and profiles the local operational context of public health program and service delivery. It is a

first step in understanding the current work of public health and will inform the discussion as Ontario moves

towards a performance management system for public health.

This report also serves an important purpose in raising awareness of the vital role public health plays in

protecting the health of Ontarians and in contributing to the provincial health system as a whole.

Towards Performance Management

Ontario’s efforts to introduce a performance management framework for public health are being

informed by the Performance Management Working Group (PMWG).

Formed in 2007, PMWG members come from diverse backgrounds and include members of

the Council of Ontario Medical Officers of Health (COMOH), the Association of Public Health

Epidemiologists in Ontario (APHEO), Public Health Research, Education and Development (PHRED)

Program, the Association of Local Public Health Agencies (alPHa), and local public health units.

The group also includes representatives from the Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care, the Ministry

of Health Promotion and the Ministry of Children and Youth Services – the three ministries that share

responsibility for providing funding and policy direction to public health units. The group’s advice

has informed the development of this report as well as continuing to address the larger performance

management framework for public health.

Introduction

3

Initial Report on Public Health 2009

Overview of the Public Health Sector

Section II:

Scope of Public Health

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines public health as “a social and political concept aimed at

improving health, prolonging life and improving the quality of life among whole populations through health

promotion, disease prevention and other forms of health intervention.”

13

The WHO notes a distinction

between the traditional model of public health and an emerging concept of public health, which emphasizes:

• asignificantlydifferentunderstandingofhowlifestylesandlivingconditions(social,economicand

physical environments) determine health status

• theneedtomobilizeresourcesandmakesoundinvestmentsinpolicies,programsandserviceswhich

create, maintain and protect health

The public health sector has contributed to improving the health of Ontarians through initiatives such

as childhood immunizations, the control of infectious diseases, supporting parenting/early childhood

development, addressing oral health, ensuring safe water, education and inspections related to safe food

handling, the promotion of healthy sexuality, reproductive and child health, the prevention of injury, and the

prevention of chronic diseases through initiatives such as tobacco control and promotion of healthy eating.

Public health also contributes to the health of Ontarians by complementing the work of other parts of the

health care system. Through its work in addressing the determinants of health and reducing health risks to

the population, public health contributes to reducing the need for other health care services and limiting the

consequences of poor health including:

• theneedforacutemedicalcare

• long-termconsequencesofillnessandinjury,includingtheseverityandincidenceofdiseasesanddisability

• reducedincomeorlossofemployment

• prematuremortality

The public health system consists of governmental, non-governmental, and community organizations operating

at the local, provincial, and federal levels. However, the prime responsibility for program delivery in Ontario lies

with local boards of health, which comprise the public health sector. Provincial and federal level organizations

play an important role in setting policy, providing funding, issuing directives about specific programs, services

and situations, as well as coordination across jurisdictions.

There are exceptions to this indirect support of the provincial and federal governments, such as the work

of the Canadian Food Inspection Agency, which has the authority to take direct action at the community

level when necessary to protect the food supply. In addition, First Nations Band Councils and the federal

government have the responsibility for much of the delivery of public health programs on reserves.

4

In Ontario, the role of the provincial government is to:

• establishoverallstrategicdirectionandprovincialprioritiesforpublichealth

• developlegislation,regulations,standards,policies,anddirectivestosupportthosestrategicdirections

• monitorandreportontheperformanceofthepublichealthsectorandthehealthofOntarianswithregard

to public health issues

• establishfundingmodelsandlevelsoffundingforpublichealthservicedelivery

• ensurethatministry,publichealthsectorandhealthcaresystemstrategicdirectionsandexpectations

are met

Ontarians are served by 36 local boards of health that collectively cover the entire province and are individually

responsible for serving the population within their geographic borders. Approximately two-thirds of Ontario’s

boards of health are autonomous bodies created to provide public health services in their jurisdictions. For the

remainder, municipal or regional councils act as the board of health.

All boards of health in Ontario and their staff:

• havethesamestatutoryresponsibilitiesundertheHPPAfordeliveringpublichealthprogramsand

services within their communities

• mustcomplywithoverfiftyactsandregulations

• mustdeliverthesamecoresetofservicesaccordingtotheOntarioPublicHealthStandards

14

(OPHS);

local service delivery models vary based on community need, geography and other local factors

• deliverotheroptionalprogramming,withfundingfromavarietyofsources,toaddresslocalcommunity

needs and priorities

Within this document, the term “board of health” has the meaning assigned to it in Section 1 of the HPPA, and

refers to either the legal entities that provide public health programs and services within a specific geographic

region or to the governing body of the organization, depending on the context. The term “public health unit”

is used to refer to the staff complement of the organization who deliver the programs and services, which is

usually headed by a medical officer of health or by a shared leadership model of a medical officer of health

and a chief executive officer.

Legislative Framework for Public Health

Ontario’s HPPA provides the legislative mandate for boards of health. The guiding purpose of the HPPA is

to “provide for the organization and delivery of public health programs and services, the prevention of the

spread of disease and the promotion and protection of the health of the people of Ontario.”

11

Part II, Section 5 of the HPPA specifies that boards of health must provide or ensure the provision of specific

public health programs and services. The OPHS are published by the Minister of Health and Long-Term Care

under his/her authority in Section 7 of the HPPA and specify the minimum mandatory programs and services

with which all boards of health must comply.

Overview of the Public Health Sector

5

Initial Report on Public Health 2009

Determinants of Health

The health of individuals and communities is significantly influenced by complex interactions between social

and economic factors, the physical environment, and individual behaviours and living conditions. These factors

are referred to as the determinants of health, and together they play a key role in determining the health status

of the population as a whole. Determinants of health include the following:

• incomeandsocialstatus

• socialsupportnetworks

• educationandliteracy

• employment/workingconditions

• socialandphysicalenvironments

• personalhealthpracticesandcopingskills

• healthychilddevelopment

• biologyandgeneticendowment

• healthservices

• gender

• culture

• language

Public health works to address the determinants of health as the underlying causes of health inequities. This

approach is reinforced in the OPHS, which require the following types of activities by public health units:

• identificationofprioritypopulations

• adaptingprogramsandservicedeliverytomeetlocallyidentifiedpriorityneeds

• assessmentandsharinginformationofhealthinequities

• raisingawarenesswithcommunitydecisionmakersandpartners

These actions will foster more comprehensive solutions that will help improve the immediate and long-term

health of Ontarians. The OPHS incorporate and address the determinants of health, and identify a broad

range of population-based activities designed to promote health and reduce health inequities by working

with community partners.

6

Public Health Programs and Services in Ontario

In addition to delivering programs and services to meet local contexts and situations, the scope of public

health programs and services, as articulated in the OPHS, encompasses:

Chronic Diseases and Injuries: Chronic Disease Prevention

Prevention of Injury and Substance Misuse

Family Health: Reproductive Health

Child Health

Infectious Diseases: Infectious Diseases Prevention and Control

Rabies Prevention and Control

Tuberculosis Prevention and Control

Sexual Health, Sexually Transmitted Infections,

and Blood-borne infections (including HIV)

Vaccine Preventable Diseases

Environmental Health: Food Safety

Safe Water

Health Hazard Prevention and Management

Emergency Preparedness: Public Health Emergency Preparedness

Health Unit Profiles

Each of Ontario’s 36 public health units must respond to unique demographics, social conditions and

health needs within their community. The health unit profile information shown in Table 1: Health Unit

Profiles describes the local service delivery environment for each public health unit in Ontario. The table

provides context for the indicator data included in Section IV of the report. Each of the variables in the table

underscores the fact that the delivery of public health programs and services in Ontario occurs in significantly

different, multi-faceted and complex physical, cultural, social and economic environments.

For each variable, the provincial totals or averages, the minimum value, and the maximum value are shown.

The Table is organized to show the public health units according to their peer groups. A peer group is a

cluster of public health units, identified by Statistics Canada

15

as having similar social, demographic and

economic characteristics. Appendix 1 provides additional information on the definitions of peer groups.

Appendix 2 provides information on the variable definitions and data sources.

Overview of the Public Health Sector

7

Initial Report on Public Health 2009

8

% Francophone

Population

2.3%

48.2%

42.0%

1.1%

1.0%

1.2%

1.3%

0.8%

3.7%

1.2%

0.6%

5.6%

2.7%

7.4%

18.4%

26.8%

4.2%

25.2%

4.4%

0.6%

48.2%

Size of Birth Cohort

(2007)

973

1,063

2,015

1,091

1,356

1,008

1,369

569

1,434

1,214

862

1,020

4,910

1,028

1,058

1,849

1,530

297

151,304

297

31,581

% with Post Secondary

Education

49.2%

51.8%

51.1%

50.0%

53.4%

52.2%

53.1%

48.7%

57.5%

49.5%

49.4%

51.7%

55.9%

56.1%

56.3%

58.1%

57.2%

52.5%

61.4%

48.7%

71.6%

%Personsunder18years

of age in Low Income

Households (after tax)

6.5%

10.8%

9.1%

7.4%

7.0%

7.4%

8.8%

5.8%

6.8%

5.8%

5.7%

7.6%

7.4%

13.1%

11.6%

11.0%

11.3%

8.6%

13.7%

5.7%

25.4%

Housing Affordability

16.9%

19.7%

23.7%

22.2%

22.8%

21.9%

22.9%

19.4%

22.5%

20.4%

20.2%

19.4%

26.1%

19.7%

25.3%

20.9%

19.9%

19.6%

27.7%

16.9%

36.5%

Employment Rate

60%

57%

61%

64%

61%

62%

57%

65%

60%

66%

70%

58%

64%

52%

55%

57%

58%

54%

63%

52%

70%

# First Nations

39

10

1

0

2

0

1

0

0

0

0

1

4

8

6

13

25

2

127

0

39

% Immigrants

5.5%

3.2%

6.0%

13.2%

8.4%

11.1%

9.6%

8.0%

7.6%

10.9%

9.4%

6.2%

11.8%

9.7%

5.8%

6.2%

9.3%

4.1%

28.3%

3.2%

50.0%

Population Density (km

2

)

(2007)

0.5

0.3

37.5

48.3

18.9

39.1

19.5

18.1

26.9

52.3

34.8

6.7

56.6

2.7

7.5

4.3

0.7

2.4

14.1

0.3

4,207.9

Population Growth Rate

(2002-2007)

-3.2%

-4.5%

1.5%

6.2%

1.2%

2.2%

3.4%

-1.0%

2.1%

2.9%

0.3%

0.2%

8.0%

-1.8%

0.1%

0.4%

-3.5%

-4.4%

5.8%

-4.5%

20.8%

Population (2007)

80,042

87,305

199,227

90,758

161,896

111,684

175,187

61,373

170,205

106,574

77,156

100,468

494,081

119,121

125,383

198,265

155,079

34,564

12,803,861

34,564

2,651,717

Size of Region (km

2

)

171,288

266,291

5,308

1,881

8,586

2,858

8,988

3,397

6,329

2,039

2,218

14,980

8,731

44,308

16,802

46,475

235,531

14,125

907,574

630

266,291

Variable

Public Health Unit

Northwestern Health Unit

Porcupine Health Unit

The Eastern Ontario

Health Unit

Elgin-St. Thomas Health Unit

Grey Bruce Health Unit

Haldimand-Norfolk

Health Unit

Haliburton, Kawartha, Pine

Ridge District Health Unit

Huron County Health Unit

Leeds, Grenville and

Lanark District Health Unit

Oxford County Health Unit

Perth District Health Unit

Renfrew County and District

Health Unit

Simcoe Muskoka District

Health Unit

The District of Algoma

Health Unit

North Bay Parry Sound

District Health Unit

Sudbury and District

Health Unit

Thunder Bay District

Health Unit

Timiskaming Health Unit

Ontario

Ontario Total

Ontario Minimum

Ontario Maximum

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

Peer Group

Rural

Northern

Regions

Mainly Rural

Sparsely Populated

Urban-Rural Mix

Table 1: Health Unit Profiles

Overview of the Public Health Sector

9

Initial Report on Public Health 2009

Board of Health

Governance Model

Autonomous

Autonomous

Autonomous

Autonomous

Autonomous

Single-Tier

Autonomous

Autonomous/

Integrated

Autonomous

Regional

Autonomous

Autonomous

Autonomous

Autonomous

Autonomous

Autonomous

Autonomous

Autonomous

# Municipalities

19

13

15

8

17

2

12

9

22

8

6

18

24

22

31

19

15

24

413

1

31

# Small Drinking Water

Systems(2008)

1,196

369

660

110

1,304

344

924

256

825

216

398

719

1,483

649

999

790

791

225

17,879

0

1,483

# School Boards

4

9

4

2

3

2

4

2

3

3

2

7

6

4

5

10

6

4

154

2

10

# Schools

48

75

136

36

69

55

77

34

84

53

37

61

209

86

79

129

86

29

4,927

29

808

# Personal Service

Settings (estimated)

95

186

343

82

281

148

256

103

227

121

104

137

610

374

178

350

223

54

18,560

54

3,469

# Licenced Day Nurseries

53

28

61

12

71

24

71

12

69

33

25

25

142

53

57

98

45

21

4,620

12

924

# Hospital Sites

8

11

4

1

11

3

5

5

9

3

3

5

7

6

5

8

6

3

209

1

21

# Long-term Care Homes

12

13

18

8

30

10

20

9

14

19

10

14

29

12

11

11

15

8

777

7

86

# Food Premises (2006)

512

641

973

552

1,567

954

1,636

443

1,253

603

450

798

3,782

880

968

1,286

1,737

404

76,163

404

13,367

Cost of Nutritious Food

Basket for a Family of

Four(2008)

$176

$157

$144

$140

$145

$134

$141

$139

$138

$136

$137

$141

$134

$144

*

$141

$157

$143

$141

$130

$176

% Speaking neither

English nor French

0.7%

0.3%

0.2%

0.9%

0.3%

0.5%

0.1%

0.7%

0.1%

0.4%

0.7%

0.1%

0.3%

0.4%

0.1%

0.2%

0.6%

0.0%

2.2%

0.0%

5.3%

Variable

Public Health Unit

Northwestern Health Unit

Porcupine Health Unit

The Eastern Ontario

Health Unit

Elgin-St. Thomas Health Unit

Grey Bruce Health Unit

Haldimand-Norfolk

Health Unit

Haliburton, Kawartha, Pine

Ridge District Health Unit

Huron County Health Unit

Leeds, Grenville and

Lanark District Health Unit

Oxford County Health Unit

Perth District Health Unit

Renfrew County and District

Health Unit

Simcoe Muskoka District

Health Unit

The District of Algoma

Health Unit

North Bay Parry Sound

District Health Unit

Sudbury and District

Health Unit

Thunder Bay District

Health Unit

Timiskaming Health Unit

Ontario

Ontario Total

Ontario Minimum

Ontario Maximum

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

Peer Group

Rural

Northern

Regions

Mainly Rural

Sparsely Populated

Urban-Rural Mix

Table 1: Health Unit Profiles (cont’d)

* Health Unit did not have a Registered Dietitian in 2008 and therefore data is unavailable. The 2007 amount was $130.65.

10

% Francophone

Population

1.2%

3.0%

1.5%

2.4%

2.9%

2.5%

1.6%

3.6%

1.3%

2.0%

2.1%

18.6%

1.3%

1.5%

1.3%

3.6%

1.1%

1.5%

4.4%

0.6%

48.2%

Size of Birth Cohort

(2007)

1,444

1,165

5,416

1,582

1,763

1,191

4,858

3,906

1,188

6,352

5,645

9,245

16,345

6,077

2,891

4,370

10,837

31,581

151,304

297

31,581

% with Post Secondary

Education

52.1%

49.0%

58.1%

52.5%

61.8%

58.1%

61.5%

56.1%

58.3%

60.1%

69.3%

71.6%

62.9%

58.1%

57.4%

55.4%

67.1%

66.4%

61.4%

48.7%

71.6%

%Personsunder18years

of age in Low Income

Households (after tax)

12.1%

10.1%

18.6%

10.2%

9.5%

7.8%

12.5%

10.5%

9.7%

8.9%

7.8%

15.2%

14.5%

9.1%

6.7%

12.2%

11.5%

25.4%

13.7%

5.7%

25.4%

Housing Affordability

23.4%

22.3%

27.4%

24.2%

26.3%

19.1%

25.8%

25.4%

26.8%

25.9%

23.3%

24.4%

32.0%

23.1%

24.1%

23.7%

29.7%

36.5%

27.7%

16.9%

36.5%

Employment Rate

64%

61%

60%

58%

60%

60%

63%

61%

58%

67%

69%

65%

67%

68%

69%

60%

67%

60%

63%

52%

70%

# First Nations

2

2

0

1

0

3

3

0

2

1

0

0

0

0

0

0

1

0

127

0

39

% Immigrants

12.9%

10.1%

25.4%

8.2%

11.4%

11.6%

20.0%

18.0%

9.5%

20.3%

24.8%

22.3%

48.6%

22.3%

16.1%

22.4%

42.9%

50.0%

28.3%

3.2%

50.0%

Population Density (km

2

)

(2007)

121.3

44.4

465.2

23.2

29.1

44.1

132.2

234.0

35.1

236.0

484.9

304.6

1,043.9

362.7

64.1

218.1

553.9

4,207.9

14.1

0.3

4,207.9

Population Growth Rate

(2002-2007)

4.6%

-1.3%

1.0%

2.2%

0.4%

0.0%

2.9%

1.2%

1.4%

10.7%

16.5%

3.5%

19.7%

7.0%

5.6%

1.8%

20.8%

1.3%

5.8%

-4.5%

20.8%

Population (2007)

136,865

109,612

519,741

163,120

187,843

132,228

438,438

433,946

133,583

595,354

468,980

846,169

1,296,505

496,370

265,319

403,797

975,906

2,651,717

12,803,861

34,564

2,651,717

Size of Region (km

2

)

1,129

2,471

1,117

7,028

6,449

3,002

3,317

1,854

3,806

2,523

967

2,778

1,242

1,369

4,142

1,851

1,762

630

907,574

630

266,291

Variable

Public Health Unit

Brant County Health Unit

Chatham-Kent Health Unit

City of Hamilton Health Unit

Hastings and Prince Edward

Counties Health Unit

Kingston, Frontenac and

Lennox and Addington

Health Unit

Lambton Health Unit

Middlesex-London

Health Unit

Niagara Regional Area

Health Unit

Peterborough County-City

Health Unit

Durham Regional Health Unit

Halton Regional Health Unit

City of Ottawa Health Unit

Peel Regional Health Unit

Waterloo Health Unit

Wellington-Dufferin-Guelph

Health Unit

Windsor-Essex County

Health Unit

York Regional Health Unit

City of Toronto Health Unit

Ontario

Ontario Total

Ontario Minimum

Ontario Maximum

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

Peer Group

Urban/Rural MixUrban Centres

Metro

Centre

Table 1: Health Unit Profiles (cont’d)

Overview of the Public Health Sector

11

Initial Report on Public Health 2009

Table 1: Health Unit Profiles (cont’d)

Board of Health

Governance Model

Autonomous

Autonomous/

Integrated

Single-Tier

Autonomous

Autonomous

Autonomous/

Integrated

Autonomous

Regional

Autonomous

Regional

Regional

Single-Tier

Regional

Regional

Autonomous

Autonomous

Regional

Semi-

Autonomous

# Municipalities

2

1

1

17

9

11

9

12

9

8

4

1

3

7

16

9

9

1

413

1

31

# Small Drinking Water

Systems(2008)

114

94

246

580

805

64

507

294

494

395

261

476

130

148

393

61

559

0

17,879

0

1,483

# School Boards

3

3

4

5

4

4

4

4

4

6

4

4

4

4

5

4

4

4

154

2

10

# Schools

64

50

184

78

92

60

164

196

55

214

147

306

386

173

97

171

299

808

4,927

29

808

# Personal Service

Settings (estimated)

200

189

717

204

286

140

550

700

287

646

516

1,100

1,200

707

327

500

2,950

3,469

18,560

54

3,469

# Licenced Day Nurseries

30

48

204

65

95

51

133

154

50

169

250

326

433

123

77

163

425

924

4,620

12

924

# Hospital Sites

2

3

8

5

4

3

8

10

1

6

4

10

3

3

8

3

4

21

209

1

21

# Long-term Care Homes

7

8

29

26

11

10

18

46

17

26

18

40

36

33

30

24

49

86

777

7

86

# Food Premises (2006)

786

808

2,988

1,265

1,100

640

2,714

2,655

704

3,349

2,655

5,723

5,013

2,175

1,460

2,455

6,867

13,367

76,163

404

13,367

Cost of Nutritious Food

Basket for a Family of

Four(2008)

$149

$138

$136

$137

$142

$135

$139

$135

$145

$141

$133

$140

$130

$141

$149

$135

$143

$136

$141

$130

$176

% Speaking neither

English nor French

0.4%

0.5%

1.7%

0.2%

0.3%

0.2%

1.1%

0.6%

0.1%

0.5%

0.8%

1.3%

3.7%

1.5%

0.8%

1.7%

4.0%

5.3%

2.2%

0.0%

5.3%

Variable

Public Health Unit

Brant County Health Unit

Chatham-Kent Health Unit

City of Hamilton Health Unit

Hastings and Prince Edward

Counties Health Unit

Kingston, Frontenac and

Lennox and Addington

Health Unit

Lambton Health Unit

Middlesex-London

Health Unit

Niagara Regional Area

Health Unit

Peterborough County-City

Health Unit

Durham Regional Health Unit

Halton Regional Health Unit

City of Ottawa Health Unit

Peel Regional Health Unit

Waterloo Health Unit

Wellington-Dufferin-Guelph

Health Unit

Windsor-Essex County

Health Unit

York Regional Health Unit

City of Toronto Health Unit

Ontario

Ontario Total

Ontario Minimum

Ontario Maximum

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

Peer Group

Urban/Rural MixUrban Centres

Metro

Centre

12

13

Initial Report on Public Health 2009

Report Development

The process of developing this report began with careful consideration of how public reporting contributes

to performance management. Meeting the longer term objective of publishing provincial performance reports

reflective of the public health mandate will require time and resources to develop new measures of program

outcomes and to address data collection issues.

While this report is not intended as a performance report, it does provide a status update on a range of

indicators related to public health practice. Over time, as new data sources and indicators are developed,

these basic indicators may be replaced by more appropriate measures. The development of this report was

informed by the decision to avoid trying to directly link the indicators to the standards in the OPHS, which

were released during the report’s development. This decision was made because it was seen as inappropriate

to begin to publicly report on local public health performance until public health units have had time to adapt

to the new standards and begin measuring their impact at the outcome level. These outcome level measures

will need to be identified and developed as this public health performance management work continues.

In presenting the scope of public health in Ontario at both the provincial and local levels, an important

consideration was to use reliable data that could be presented at the health unit level. The selection of

indicators, therefore, was contingent upon the availability of reliable and comprehensive data. During the

indicator selection process a wide range of indicators, other than those presented, were considered for

inclusion but were not selected for a variety of reasons, including unavailability of consistent and reliable data.

To guide the selection of indicators for the report, several different frameworks, or approaches to

performance management indicator reporting were evaluated by the PMWG, including:

• balancedscorecardapproach

• strategymappingapproach

• attributesofahighperformingsystem

Through discussion and research on the use of these frameworks in other sectors and other jurisdictions, it

was determined that each of these approaches has merits and limitations when applied to the public health

sector in Ontario.

Balanced Scorecard Approach

The Balanced Scorecard, as developed by ICES for public health, identifies four quadrants:

1) Health Determinants and Status, 2) Community Engagement, 3) Resources and Services,

4) Integration and Responsiveness for the reporting of information on a system or organization.

16

Several public health units have used the Balanced Scorecard approach for local public reporting in the recent

past. However, the lack of consistent and available data for all health units for two of the four quadrants

(Community Engagement, and Integration and Responsiveness) would compromise the usefulness of this tool

for provincial reporting at this time.

Performance of the Public Health Sector

Section III:

14

Strategy Mapping Approach

A strategy mapping approach was explored as a framework to guide measurement of performance in public

health. This approach was helpful in understanding the strategic components of public health, but was found

to be too high level for use as a framework for this report.

Attributes of a High Performing System

Determining the “attributes of a high performing system” that could be used in relation to the public health

sector was approached by first researching the performance dimensions used in other jurisdictions and in

other health care sector reports. Through discussion with the PMWG, the following five key dimensions were

identified as appropriate for capturing the key aspects of Ontario’s public health sector.

1) Effectiveness

2) Capacity

3) Equitable

4) Community Partnership

5) Effectively Governed and Managed

Each of these approaches provides an organized way of presenting performance information. The PMWG

determined that any one of these performance reporting approaches could be used as part of the process for

selecting potential indicators. In fact, an exercise was completed which showed that the indicators that were

available for use at this time could be mapped into all of the above frameworks. This shows that the different

frameworks have significant conceptual overlap, and any one of them could be used to assess public health

performance.

As the report development process continued, it was determined that focussing on performance reporting

at this time was inappropriate, due mainly to the lack of performance related indicators and consistent

data to support them, and because of the early stage of development of the new approach to performance

management within the public health sector.

While the work of developing the report and the selection of indicators was informed by the earlier work on

performance reporting frameworks, a decision was made to not use any specific reporting framework for this

report.

Performance of the Public Health Sector

15

Initial Report on Public Health 2009

Development of Indicators

Indicators used in existing reports on public health and population health were considered as part of the

context for informing Ontario’s public health reporting. These existing reports included:

• Q Monitor: 2008 Report on Ontario’s Health System(OntarioHealthQualityCouncil)

17

• Ontario Health System Scorecard 2007/08 (Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care)

18

• Healthy Canadians: A Federal Report on Comparable Health Indicators 2006 (Health Canada)

19

• Report on the State of Public Health in Canada 2008 (Public Health Agency of Canada)

20

• Developing a Balanced Scorecard for Public Health (Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences)

16

• Towards Outcome Measurement (Public Health Research Education and Development Program)

21

Many public health units have also produced and will continue to produce, local health status reports or

performance reports, which may contain similar or related indicators with more analysis and interpretation

on the impact of these measures within their communities.

The indicators presented in this report are intended to complement and enhance our understanding of the

scope and impact of public health across Ontario, whereas many other health reports focus on information

about the impact of the health care system or the health of the general population.

A modified Delphi process was employed to select indicators for this report, using a number of rationales,

including:

• strategicpriorityforpublichealth

• providessector-levelinformation

• provideslocal-levelinformation

• theabilityofpublichealthtoinfluenceoutcomesinthisarea

• whethertheindicatorrelatestomultipleprogramareas

Selection criteria that were used to determine the final set of indicators required that each indicator be:

• relevant,feasible,andscientificallysound

• supportedbycurrentlyavailabledatathatcouldbereportedatthehealthunitlevel

• partofasetwhichreflectsthescopeofpublichealthpractice

• meaningfulindescribingthescopeofpublichealthatboththeprovincialandlocallevels

This report will allow local public health officials and other stakeholders to consider how a board of health is

currently providing programs and services alongside of its peers. But this is only a starting point which also

requires an understanding of local context and conditions, which must be taken into account. It is expected

that public reporting will evolve as performance management in public health develops, consistent with the

OPHS and Protocols, and that this will drive the development of better indicators and new data sources.

16

Case Studies

Throughout the report, examples of public health initiatives that are currently in place at the local level have

been included as case studies. The case studies provide additional context to the work of the public health

sector in Ontario.

Case study submissions were requested from public health units to showcase innovative or exciting local

practices. The case studies included in the report are drawn from among the large number of submissions

received from public health units. A full list of submissions can be found in the report’s webpage, at

www.health.gov.on.ca/english/public/pub/pubhealth/init_report/index.html.

While examples of local practice are attributed to specific public health units, please note that this does not

necessarily represent exclusive practice as other public health units may also deliver similar programs.

The case studies were selected to reflect a range of program areas, populations served, levels of interaction

and types of local practice. While the case studies are intended to complement the information in the report,

they do not relate directly to any specific indicators, particularly because they were selected as examples of

the work of public health that is not currently well represented in the available data. There is no association

between the indicators and the placement of the case studies.

i

i

The names of the public health units used in this section reflect locally used health unit names, and may differ from the legal names

used by the ministry, as shown in the data tables.

Performance of the Public Health Sector

17

Initial Report on Public Health 2009

Indicators

Section IV:

This section contains narratives for each of the 34 selected indicators. The narratives provide background and

contextual information on the importance of the indicator in public health practice and give specific examples

of the role of public health in relation to that indicator. There is some duplication of text for those indicators

which are closely related, particularly in terms of describing public health interventions. This structure was

chosen so that each indicator narrative would provide the same level of information when read independently.

The corresponding data for each indicator can be found in Table 2: Indicators by Public Health Unit and

information on indicator definitions, including sources and data limitations, can be found in Appendix 3.

The data were compiled from existing data sources, such as Statistics Canada or the ministry’s Integrated

Public Health Information System (iPHIS) system, with the exception of the governance and accountability

data, which were collected directly from public health units via a survey.

For each indicator, the provincial totals or averages, the minimum value, and the maximum value are shown.

The table is organized to show the public health units according to their peer groups, as described earlier in

the health unit profile section.

Group A – Population Health Indicators

1. Teen Pregnancy

2. Low Birth Weight

3. Breastfeeding Duration

4. Postpartum Contact

5. Smoking Prevalence

6. Youth Lifetime Smoking Abstinence

7. Adult Heavy Drinking

8. YouthHeavyDrinking

9. Physical Activity Index

10. Healthy Body Mass Index

11. Fruit and Vegetable Consumption

12. Fall-Related Hospitalizations among Seniors

13. Enteric Illnesses Incidence

14. Respiratory Infection Outbreaks in Long-Term Care Homes

15. Chlamydia Incidence

16. Immunization Coverage for Hepatitis B

17. Immunization Coverage for Measles, Mumps and Rubella

18. AdverseWaterQualityIncidents

18

Group B – Governance and Accountability Indicators

19. Total Board of Health Expenditures

20. Board of Health Expenditure Variance

21. Expenditures on Training and Professional Development

22. Number of FTEs by Job Category

23. Number of Vacant Positions by Job Category

24. Employment Status of Medical Officers of Health

25. Staff Length of Service

26. Familiarity with Public Health Unit Programs and Services

27. Issuance of a Health Status Report

28. StrategicPlan

29. Emergency Response Plan Tested

30. Accreditation Status

31. Medical Officer of Health Performance Evaluation

32. Medical Officer of Health Reporting Relationships

33. Board Member Orientation

34. Board Self-Evaluation

Indicators

19

Initial Report on Public Health 2009

20

Notes:

* Ontario value is not provided

†

Note that an amalgamation occurred in these health units during the period for which data is shown

E

Warning of high variability associated with estimates

F

Estimates of unreliable quality and could not be reported

Table 2: Indicators by Public Health Unit

Population Health Indicators

Physical activity index

(percent)

56%

51%

57%

53%

52%

49%

55%

52%

58%

44%

48%

51%

57%

52%

54%

55%

52%

49%

50%

43%

64%

Youth heavy drinking

(percent)

34%

E

51%

34%

E

45%

27%

E

46%

E

33%

E

F

35%

E

45%

E

F

25%

E

34%

E

34%

65%

44%

18%

E

F

25%

12%

E

65%

Adult heavy drinking

(percent)

48%

49%

45%

36%

54%

48%

46%

43%

50%

42%

41%

43%

49%

48%

43%

47%

51%

50%

37%

24%

54%

Youth lifetime smoking

abstinence (percent)

69%

48%

E

75%

67%

E

77%

74%

56%

E

81%

70%

70%

91%

80%

80%

79%

62%

E

62%

85%

81%

E

81%

48%

E

92%

Smoking prevalence

(percent)

25%

E

28%

24%

29%

26%

28%

27%

23%

29%

34%

18%

30%

24%

29%

30%

29%

29%

25%

*

16%

34%

Postpartum contact

(percent)

94.2%

86.8%

88.4%

89.4%

83.6%

73.8%

83.4%

77.2%

92.0%

93.7%

80.2%

85.3%

92.7%

89.3%

90.3%

95.0%

87.5%

75.4%

80.8%

58.2%

95.8%

Breastfeeding duration

(percent)

48%

E

33%

E

35%

44%

E

53%

49%

E

43%

45%

E

54%

53%

39%

E

31%

E

50%

†

46%

E

45%

†E

38%

44%

F

50%

31%

E

65%

Low birth weight (rate)

20.9

33.9

36.7

49.0

39.2

40.7

36.3

46.6

36.2

42.2

35.8

41.2

41.0

51.8

30.9

41.1

41.5

41.8

47.9

20.9

67.5

Teen pregnancy (rate)

60.8

53.1

32.5

28.2

26.4

22.8

30.6

22.1

25.3

33.5

23.8

29.0

26.8

42.5

31.4

32.6

44.6

42.6

25.7

9.5

60.8

Indicator

Public Health Unit

Northwestern Health Unit

Porcupine Health Unit

The Eastern Ontario

Health Unit

Elgin-St. Thomas Health Unit

Grey Bruce Health Unit

Haldimand-Norfolk

Health Unit

Haliburton, Kawartha, Pine

Ridge District Health Unit

Huron County Health Unit

Leeds, Grenville and

Lanark District Health Unit

Oxford County Health Unit

Perth District Health Unit

Renfrew County and District

Health Unit

Simcoe Muskoka District

Health Unit

The District of Algoma

Health Unit

North Bay Parry Sound

District Health Unit

Sudbury and District

Health Unit

Thunder Bay District

Health Unit

Timiskaming Health Unit

Ontario

Ontario Total

Ontario Minimum

Ontario Maximum

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

Peer Group

Rural

Northern

Regions

Mainly Rural

Sparsely Populated

Urban-Rural Mix

Indicators

21

Initial Report on Public Health 2009

Notes:

* Ontario value is not provided

†

Note that an amalgamation occurred in these health units during the period for which data is shown

E

Warning of high variability associated with estimates

F

Estimates of unreliable quality and could not be reported

Table 2: Indicators by Public Health Unit (cont’d)

Population Health Indicators

Adverse water quality

incidents (number)

207

86

172

35

234

101

202

165

153

81

30

179

446

138

210

217

157

43

4,458

13

446

Immunization coverage

for Measles, Mumps and

Rubella (percent)

95.7%

97.8%

82.4%

97.2%

95.6%

20.7%

95.6%

95.4%

52.2%

89.3%

96.0%

86.4%

44.2%

94.6%

67.8%

93.8%

97.4%

96.8%

84.9%

20.7%

97.8%

Immunization coverage

for Hepatitis B (percent)

88.3%

86.8%

78.6%

67.9%

90.7%

78.3%

75.1%

87.1%

74.0%

81.2%

85.3%

76.9%

70.9%

89.0%

79.6%

77.7%

88.4%

73.6%

79.8%

65.2%

95.2%

Chlamydia incidence

(rate)

678.9

303.2

99.7

101.6

159.1

102.3

159.6

78.9

122.8

126.4

138.9

149.0

169.9

276.9

238.3

292.6

388.3

203.5

219.8

78.9

678.9

Respiratory infection

outbreaks in LTC homes

(number)

0

3

23

8

14

1

10

8

8

9

13

4

17

0

16

9

0

8

602

0

113

Enteric illnesses

incidence (rate)

47.3

41.3

78.3

51.9

119.7

89.7

84.5

164.1

56.2

72.6

150.5

75.8

64.4

46.1

48.4

40.0

44.1

64.1

88.7

40.0

164.1

Fall-related

hospitalizations among

seniors (rate)

2,053.8

1,619.6

1,596.1

1,335.7

1,792.5

1,641.2

1,445.7

2,030.7

1,618.9

1,850.3

1,493.1

2,371.5

1,581.6

1,576.8

1,741.6

1,571.9

1,663.4

2,022.3

1,309.5

942.6

2,371.5

Fruit and vegetable

consumption (percent)

36%

41%

44%

42%

47%

41%

38%

48%

40%

39%

46%

36%

41%

34%

45%

45%

38%

45%

42%

29%

50%

Healthy body mass

index (percent)

33%

E

39%

38%

51%

39%

42%

38%

38%

48%

42%

38%

35%

42%

38%

44%

43%

45%

36%

47%

33%

E

55%

Indicator

Public Health Unit

Northwestern Health Unit

Porcupine Health Unit

The Eastern Ontario

Health Unit

Elgin-St. Thomas Health Unit

Grey Bruce Health Unit

Haldimand-Norfolk

Health Unit

Haliburton, Kawartha, Pine

Ridge District Health Unit

Huron County Health Unit

Leeds, Grenville and

Lanark District Health Unit

Oxford County Health Unit

Perth District Health Unit

Renfrew County and District

Health Unit

Simcoe Muskoka District

Health Unit

The District of Algoma

Health Unit

North Bay Parry Sound

District Health Unit

Sudbury and District

Health Unit

Thunder Bay District

Health Unit

Timiskaming Health Unit

Ontario

Ontario Total

Ontario Minimum

Ontario Maximum

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

Peer Group

Rural

Northern

Regions

Mainly Rural

Sparsely Populated

Urban-Rural Mix

Initial Report on Public Health 2009

22

Table 2: Indicators by Public Health Unit (cont’d)

Governance and Accountability Indicators

Number of FTEs by job category

Librarian

1.0

0.0

1.0

0.0

0.0

0.0

0.0

0.0

0.0

0.0

0.0

0.0

0.6

0.0

0.0

1.0

1.0

0.0

20.1

0.0

4.0

Heart Health Coordinator

1.0

1.0

1.0

0.0

0.0

1.0

1.0

1.0

1.0

1.0

1.0

0.0

2.0

1.0

1.0

1.0

1.0

1.0

29.0

0.0

2.0

Epidemiologist

2.0

1.0

1.5

1.0

1.5

1.0

1.0

1.0

1.0

1.0

1.0

0.8

2.0

0.3

1.0

2.0

1.0

1.0

72.6

0.0

11.0

Speech – Language

Pathologist

4.0

6.0

9.6

0.0

0.0

3.7

0.0

0.0

5.0

0.0

0.0

0.0

0.0

2.8

0.0

0.0

6.2

2.0

64.3

0.0

15.2

Dietitian/Nutritionist

2.0

4.0

7.0

2.0

1.0

2.5

5.0

0.5

3.0

1.4

2.6

1.0

6.0

2.0

2.8

7.9

2.5

1.0

203.1

0.5

64.5

Health Promoter

5.0

2.0

21.7

3.0

1.3

6.5

14.0

3.0

0.0

1.0

6.2

3.0

7.0

1.0

6.0

8.0

3.0

6.4

416.7

0.0

123.4

Dental Hygienist/

Dental Assistant

6.0

4.0

0.9

1.4

3.0

1.3

5.0

0.7

3.7

2.7

2.0

1.3

13.9

6.7

5.4

6.0

2.4

1.5

286.4

0.7

86.7

Dentist

0.3

0.0

0.1

0.2

0.0

0.3

0.0

0.0

0.1

0.3

0.0

0.3

0.4

0.3

0.0

0.0

0.0

0.1

54.9

0.0

32.0

Public Health Inspector

5.0

12.0

7.0

8.0

16.0

10.5

23.0

7.0

18.1

10.5

7.2

8.2

33.5

10.6

15.0

25.0

13.0

4.2

900.5

4.2

202.8

Nurse Practitioner

0.0

2.0

0.0

0.0

0.0

2.0

0.0

1.0

0.0

1.0

0.0

0.0

2.0

2.2

0.0

2.5

1.0

1.0

28.5

0.0

4.0

Registered Practical Nurse

1.0

0.0

1.4

0.0

2.0

0.0

1.0

0.0

1.0

0.0

0.0

2.0

8.9

2.6

0.0

0.0

2.0

0.0

100.3

0.0

41.4

Registered Nurse

0.0

9.0

0.0

0.5

2.0

1.9

5.0

2.8

1.0

1.0

0.8

1.0

4.5

2.5

3.8

1.1

6.9

2.0

180.1

0.0

36.0

Public Health Nurse

33.3

38.0

47.7

25.0

39.3

18.8

25.0

14.0

43.4

37.2

31.3

23.1

82.9

48.0

41.8

86.4

47.5

16.4

2,717.2

14.0

536.9

Expenditures on training and

professional development

(percent)

0.7%

0.8%

0.6%

0.6%

0.3%

0.9%

0.5%

0.9%

0.3%

0.5%

0.7%

0.7%

0.4%

0.8%

0.3%

1.6%

0.9%

1.3%

0.7%

0.1%

1.7%

BoH expenditure variance

(percent)

4.0%

-6.2%

-1.7%

-6.4%

-1.2%

-7.5%

-1.6%

-2.8%

-2.0%

-10.9%

-2.3%

-20.8%

-1.2%

0.0%

-4.5%

-1.9%

-2.5%

-1.8%

-3.3%

-20.8%

6.3%

Total BoH expenditures ($M)

13.0

10.7

14.1

6.4

10.8

7.0

15.1

6.2

10.5

6.8

6.6

6.2

28.8

16.6

14.3

15.8

15.7

5.7

837.7

5.7

193.6

Indicator

Public Health Unit

Northwestern Health Unit

Porcupine Health Unit

The Eastern Ontario

Health Unit

Elgin-St. Thomas Health Unit

Grey Bruce Health Unit

Haldimand-Norfolk

Health Unit

Haliburton, Kawartha, Pine

Ridge District Health Unit

Huron County Health Unit

Leeds, Grenville and

Lanark District Health Unit

Oxford County Health Unit

Perth District Health Unit

Renfrew County and District

Health Unit

Simcoe Muskoka District

Health Unit

The District of Algoma

Health Unit

North Bay Parry Sound

District Health Unit

Sudbury and District

Health Unit

Thunder Bay District

Health Unit

Timiskaming Health Unit

Ontario

Ontario Total

Ontario Minimum

Ontario Maximum

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

Peer Group

Rural

Northern

Regions

Mainly Rural

Sparsely Populated

Urban-Rural Mix

Indicators

23

Initial Report on Public Health 2009

Table 2: Indicators by Public Health Unit (cont’d)

Governance and Accountability Indicators

Board self-evaluation (year)

2003

n/a

2008

n/a

2006

n/a

n/a

n/a

n/a

n/a

n/a

n/a

n/a

n/a

n/a

2005

2008

n/a

12/36

=Yes

2003

2008

Board member orientation

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

35/36

=Yes

MOH reporting

relationships

MOH reporting to standing

committee (proportion)

5/8

6/8

–

–

–

4/8

–

–

–

–

2/2

–

3/3

–

16/16

–

–

–

MOH reporting to the BoH

(proportion)

13/14

7/9

13/13

9/9

13/13

4/11

10/10

12/12

9/10

16/16

10/12

7/7

10/10

10/10

8/8

9/9

10/10

9/9

MOH performance evaluation

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

–

No

Yes

Yes

No

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes