Student Publications Student Scholarship

Spring 2022

Hidden Secrets and Private Moments in Vermeer’s Paintings of Hidden Secrets and Private Moments in Vermeer’s Paintings of

Women and Letters Women and Letters

Lauren C. McVeigh

Gettysburg College

Follow this and additional works at: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/student_scholarship

Part of the Ancient, Medieval, Renaissance and Baroque Art and Architecture Commons, and the

Women's Studies Commons

Share feedbackShare feedback about the accessibility of this item. about the accessibility of this item.

Recommended Citation Recommended Citation

McVeigh, Lauren C., "Hidden Secrets and Private Moments in Vermeer’s Paintings of Women and Letters"

(2022).

Student Publications

. 987.

https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/student_scholarship/987

This is the author's version of the work. This publication appears in Gettysburg College's institutional repository by

permission of the copyright owner for personal use, not for redistribution. Cupola permanent link:

https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/student_scholarship/987

This open access student research paper is brought to you by The Cupola: Scholarship at Gettysburg College. It has

been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of The Cupola. For more information, please contact

Hidden Secrets and Private Moments in Vermeer’s Paintings of Women and Hidden Secrets and Private Moments in Vermeer’s Paintings of Women and

Letters Letters

Abstract Abstract

This paper discusses the visual details and symbols in Johannes Vermeer's paintings of women and

letters that allude to secret affairs going on behind the scenes.

Keywords Keywords

Vermeer, letters, secrets

Disciplines Disciplines

Ancient, Medieval, Renaissance and Baroque Art and Architecture | History of Art, Architecture, and

Archaeology | Women's Studies

Comments Comments

Written for ARTH 400: Seminar in Art History

This student research paper is available at The Cupola: Scholarship at Gettysburg College:

https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/student_scholarship/987

1

Hidden Secrets and Private Moments in Vermeer’s Paintings of Women and Letters

Lauren McVeigh

Professor Else

ARTH 400

April 12, 2022

2

Introduction

A woman, seated at a table, is fully focused on writing the letter in front of her as her

maid stares out into the sunlight streaming in from the stained-glass window. It appears as if one

could simply step through the frame of the painting and into the scene. What is the lady writing

in her letter? Who is she writing to? Is the maid waiting for the arrival of someone, or is she

waiting for her mistress to finish the letter? This painting, Johannes Vermeer’s Lady Writing a

Letter with her Maid, has been one of the subjects of the art historical world for hundreds of

years. (Figure 4, c. 1670–1671, National Gallery of Ireland, Dublin, Ireland) Answers to

questions surrounding Vermeer’s paintings have remained entirely ambiguous throughout the

past centuries.

The painter is notorious for his enigmatic paintings of women, especially his works of

women reading, writing, and receiving letters. Vermeer paints his female subjects in moments of

solace and silence yet leaves viewers with clues that hint at something more exciting occurring in

the background. In these particular epistolary paintings, there is an air of mystery, suspense, and

privacy that should not be overlooked. While Johannes Vermeer’s quiet, silent scenes of women,

maids, and letters seem uneventful, clues and hints scattered throughout the paintings signal that

something more intriguing is occurring outside the bounds of the canvases. As Marjorie E.

Wieseman states in “Vermeer’s Women: Secrets and Silence”, “Rather than supplying easy,

prosaic answers in the form of a completed narrative, Vermeer’s open-ended images of women

reading and writing letters leave us anxious for more, yearning to ask provocative questions of

and about the entrancing women they depict”, this eagerness for the stories within the paintings

is never-ending.

1

1

Marjorie E. Wieseman, Johannes Vermeer, H. Perry Chapman, and Wayne E. Franits.

Vermeer’s Women : Secrets and Silence. (Cambridge: Fitzwilliam Museum, 2011), 53.

3

In carefully dissecting clues that Vermeer scatters within the paintings during the Dutch

Golden Age, one may begin to understand or construct plausible meanings behind each work.

The paintings I will be focusing on include Woman in Blue Reading a Letter, Mistress and Maid,

Lady Writing a Letter with her Maid, and Girl at an Open Window Reading a Letter. (Figure 2,

3, 4, 5) Each one of these paintings is unique and highlights different visual complexities and

cultural specifics. Some of the details within the artworks that I will highlight include the

paintings within the paintings, objects inside the scenes, the women’s physicalities, and the

presence of maids. In tandem with these details, themes that this essay will discuss include the

Background on Johannes Vermeer, Scholarly Discussion, Background on the Golden Age, Dutch

Global Trade, Female Workers, Maids and Servants, Societal Expectations for Middle and

Upper-Class Women, Education, Letters and Epistolary Culture, Epistolary Guidebooks, and

Domesticity and Genre Paintings. The combination of these multiple themes and details

promotes the sense of mystery, privacy, and secrecy that can be seen in Vermeer’s paintings of

women and letters. In essence, there are firstly surface-level stories, those of women interacting

with letters or their maid. But, with an understanding of the background during which the

paintings were created, plausible, hidden stories begin to surface from imagery.

Background on Johannes Vermeer

Johannes Vermeer is an artist who spent his life in Delft, a city in the Netherlands. In the

17th-century, he experienced a great deal of fame and notoriety. Only 36 paintings have

survived, explainable by the fact that he mostly worked for private clients.

2

Vermeer is renowned

for the ambiguousness of his paintings because there are countless interpretations with no

singular answer. Since the painter’s time has long passed, the true intentions behind his works

2

Wayne E. Franits, The Cambridge Companion to Vermeer. Cambridge ;: (Cambridge

University Press, 2001), 4.

4

may never be revealed. Out of his entire collection of paintings, 20 focus on either one woman or

a woman and her maid. Notably, Vermeer delicately freezes their movement in time as they are

completely focused and enthralled with their tasks. His masterful use of soft highlights and deep

shadows emphasize the dreamy, unfocused nature that his compositions possess. The

iconographic symbolism the painter employs within each painting pulls the viewer into the

composition and unrelentingly holds their gaze. It is ultimately the viewer’s responsibility to

create the story in front of their eyes with the multiple clues scattered throughout the paintings.

Scholarly Discussion

Many scholars have proposed their respective interpretations of these works. Since there

are no unequivocal truths outlined by Vermeer about his paintings, room for different

interpretations is boundless. The interesting detail about the scholarly conversation on Vermeer

is that while each person has their judgments, the overall mystique of the paintings is thoroughly

emphasized. The scholars that I will be discussing include, but are not limited to, Jane Jelley,

Rodney Nevitt Jr., Wayne E. Franits, Marjorie E. Wieseman, Hermer J. Hermers, and Lisa

Vergara. In Jane Jelley’s book titled “Traces of Vermeer”, she focuses on the emotional qualities

of Vermeer’s women to illuminate the possible thoughts and state of each woman.

3

Jelley

comments, “In those paintings a woman reads a letter throughout an eternal moment, and there is

neither evidence of pastness (i.e., of having received that letter) nor futurity (i.e., of finishing

it).”

4

She emphasizes how the lack of clarity surrounding what is exactly going on is broadened

by Vermeer’s choice to leave the viewer wondering with a sense of timelessness. The simplicity

of the moments he depicts alongside the hazy quality his paintings uniquely possess is also noted

3

Jane Jelley. Traces of Vermeer. (First edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017), 150.

4

Ibid., 86.

5

by Jelley here. It is a somewhat wash over the paintings that give them that uniquely gentle and

soft quality.

Another notable academic includes Rodney Nevitt Jr. who was included alongside

multiple other scholars in the “The Cambridge Companion to Vermeer” which was edited by

Wayne E. Franits. Nevitt thoroughly discusses multiple aspects of the paintings including the

prevalence of themes of love in Dutch songs, music, and courtship rituals. His most eminent

contributions include that of details of the epistolary manuals used for letter writing alongside

samples of prose romance tales. Rodney Nevitt Jr. emphasizes the simplicity of Vermeer as he

suggests, “It is perhaps by having reduced his pictorial language to such simple and lucid terms

that Vermeer continues to speak to us so directly. But it is the ambiguities of that language, its

quietly interrogatory tone, that still make it equal to such a subject as love.”

5

It is this simplicity

that has surrounded scholars’ and viewers’ minds alike for years.

Also in “The Cambridge Companion to Vermeer”, Wayne E. Franits focuses on the

background of Vermeer. He notes that out of the 36 paintings in the painter’s repertoire, 20 of

them focus on women.

6

Franits accentuates the artist’s knack for organizing the symbols and

clues within the paintings to usher the viewer into potential stories behind the subjects.

7

He

summarizes the artworks as the “...externalization of seemingly inconsequential moments.”

8

Lastly, Franits notes the appearance of simple instances yet at the same time, points out how

truly challenging it is to unlock the iconographic intricacies that surround each painting.

9

5

Franits, 110.

6

Ibid., 4.

7

Ibid.

8

Ibid.

9

Ibid.

6

Next, Marjorie E. Wieseman is an academic who highlights the rise of the Dutch

domestic genre and letter-writing in the 17th-century.

10

In her book, “Vermeer’s Women: Secrets

and Silence”, she spotlights her work on the combination of these two factors and asserts that

some of Vermeer’s paintings communicate themes of feminine literacy over love.

11

She

expresses that, “His world of letters is an exclusively feminine one: elegant women either read

letters in solitude with hushed concentration, look out at the viewer or engage in mute exchanges

with their maids, ‘creating subtle dramas that linger unsolved within a world governed by codes

of domestic conduct.’”

12

This subtlety is crucial to highlight when studying the artist’s work

because it is an element at the forefront of his craft. She mainly shows how the stillness of his

works creates the perfect landscape for letters.

13

Also, Wieseman acknowledges how the

domesticity of Vermeer's paintings usher in the theme of secrecy since the concept of the home

as a private retreat from the outside world was rising to popularity in the 17th-century.

14

Privacy

and secrecy were emphasized by how rooms were becoming more distinct and separate from

each other.

15

The last main scholar I will involve in my discussion is Lisa Vergara, who is another

contributor to “The Cambridge Companion to Vermeer”. She underlines the main areas of the

simple nature of Vermeer’s subjects, the presence of servants, gender implications, the theme of

love, and lastly the domestic genre. She discloses, “The growing market for pleasing images of

youthful femininity, the identification of high-class burgher households with women in Dutch

paintings of domestic life, and the aesthetic appeal to Vermeer of ordered, sunlit spaces

10

Wieseman, 7.

11

Ibid., 112.

12

Ibid., 50.

13

Ibid.

14

Ibid.

15

Ibid.

7

associated with such households…this combination of factors makes Vermeer’s attention to

women in his art easier to understand.”

16

Her thoughts on how Vermeer expressed his art connect

to the conditions of the time as it relates to women in particular. This background Vergara offers

as a context for studying Vermeer’s work is essential because it clarifies the historical

circumstances present at the artist’s time so that one may further understand his artistic choices

and actions.

Background on the Golden Age

To understand the context of the time in which Vermeer’s women lived, it is beneficial to

have a grasp on the history of the Dutch Golden Age. Notably, the Dutch viewer and painter in

the 17th-century would have interpreted the artist’s paintings through a different light than that

of the 20th-century viewer. This background will benefit in understanding some of Vermeer’s

artistic choices. In the 17th-century, the Netherlands was a bustling country with a highly

urbanized and flourishing society that was centralized in the major cities. The country’s trade

empire was booming, leading to more labor opportunities and development than ever seen

before. The overall wealth of the prosperous economy was somewhat distributed between social

classes with the middle class rising to new prominence.

17

This period of affluence in the

economy, overall sense of equality between peoples, religious freedom, and bourgeois ideals is

commonly referred to as, “The Golden Age”.

18

In “The Cambridge Companion to The Dutch

Golden Age”, Helmer J. Helmers writes, “...observers of the Dutch miracle have asked

themselves how a small country, with barely two million inhabitants, could have achieved

16

Franits, 5.

17

Ibid., 1.

18

Helmer J. Helmers, and Geert H. Janssen. The Cambridge Companion to the Dutch Golden

Age. (First edition. Cambridge ;: Cambridge University Press, 2018), 395.

8

prominence in such varied fields of human endeavor and competition.”

19

The ideal combination

of climates led to an extreme expansion or sort of renaissance movement in all areas of Dutch

art, literature, trade, and labor. Ultimately, the Netherlands was in a perfect location for trade

with the rest of Europe which led to higher wages and more job opportunities that benefited the

rest of the society. An understanding of certain elements within 17th-century Dutch culture will

help to unlock the secrets of Vermeer’s paintings. The areas I will highlight include Dutch

Global Trade, Female Workers, Maids and Servants, Societal Expectations for Middle and

Upper-Class Women, Education, Letters, Epistolary Guidebooks, and Domesticity and Genre

Paintings

Dutch Global Trade

The location of the city of Amsterdam was perfect for trade, so the city eventually

became known as, “...the world’s entrepôt: the place where goods from all corners of the globe

were shipped and warehoused, and from where they were re-exported to places in Europe and

beyond'', as described by Helmer J. Helmers in “The Cambridge Companion to The Dutch

Golden Age.”

20

In the 17th-century, if someone needed to purchase imported goods like exotic

textiles, spices, or grains, Amsterdam was the place where they knew they would find anything

and everything. In light of these global connections in the city, Vermeer’s paintings were known

to have objects of exotic and imported nature within them. In “Vermeer’s Hat: The Seventeenth

Century and the Dawn of the Global World”, Timothy Brook identifies a lavish Turkish carpet

strewn across the table in the foreground of Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window along with

a blue and white dish from China.

21

He suggests, “This dish, appropriately for a picture painted

19

Ibid., 1.

20

Helmers, 160.

21

Timothy Brook. Vermeer’s Hat : the Seventeenth Century and the Dawn of the Global World.

(1st U.S. ed. New York: Bloomsbury Press, 2008), 54.

9

in the town that created delftware, will be the door through which we head out of Vermeer’s

studio and down a corridor of trade routes leading from Delft to China.”

22

It is objects like these

that connect a small painting by a Dutch painter to a porcelain craftsman halfway across the

world in China. This is one of many ways the centralization of people, goods, and information,

helped Amsterdam transition into a capital city of sorts where people could find out all the latest,

up-to-date information along with countless imported goods.

Female Workers

Despite global trade bringing in new opportunities to the Netherlands, it is important to

recognize that not every kind of person benefited from this unparalleled success within the

country. Women, children, immigrants, and poorer classes of people consistently did not reap the

same benefits from this time as men did.

23

Although almost fifty percent of Dutch women

worked in the market areas, they consistently earned much less in wages than men did and were

barred from performing in the most high-paying job areas.

24

Ronni Baer describes this in “Class

Distinctions Dutch Painting in the Age of Rembrandt and Vermeer” when they claim, “When

women were paid for their work, they earned, on average, only one third to two-thirds of what

adult males were paid.”

25

In spite of the Netherlands being known as a somewhat progressive

country, with half of the female population working, some middle and all upper-class women

were expected to stay within the spheres of the home. Helmer J. Helmers also points out how the

average price of Vermeer’s paintings was equivalent to a middle class salary.

26

This identifies

22

Ibid., 56.

23

Helmers, 163.

24

Ronni Baer, Henk F. K. van. Nierop, Herman. Roodenburg, Eric Jan Sluijter, Marieke de.

Winkel, Sanny de Zoete, and Diane Webb. Class Distinctions : Dutch Painting in the Age of

Rembrandt and Vermeer. (First edition. Boston: MFA Publications, Museum of Fine Arts,

Boston, 2015), 198.

25

Ibid., 198.

26

Helmers, 286.

10

that most of the painter’s clients were of the middle-class to the upper-classes, so it is clear that

the women portrayed in Vermeer’s paintings with letters can be assumed to be members of the

middle or upper-classes. In “Class Distinctions: Dutch Painting in the Age of Rembrandt and

Vermeer” Ronni Baer notes, “Much of women’s work outside the home might best be described

as ancillary–assisting in the craftsman’s workshop, the store, or market stall; performing

industrial or agricultural work that required little skill…Often this labor was seasonal, performed

within the family business, or unpaid.”

27

Baer brings to light how the main women who could

work outside of the home were of the middle class.

28

Since Vermeer strictly depicts his female

subjects within their domestic interiors, it is most likely that they were members of the middle or

upper-classes. They would have been expected to fulfill the roles of the housewife, not working

outside of the home, and this is emphasized by how three of his paintings of letters show the

mistress alongside her maid, hinting at her higher status.

Maids and Servants

Maids are the subject of five paintings from Vermeer’s collection; two of these artworks

focus exclusively on the servant while the other three show her alongside her mistress. In

“Foregrounding the Background: Images of Dutch and Flemish Household Servants”, Diane

Wolfthal explains why servants and maids were central figures in paintings. She says that a

painter may have wanted to grant the servant an important or even solitary role to, “...express his

affection for or appreciation of a loyal member of his household.”

29

The close, intimate ties that

maids had to their employers could even be considered as close as a familial bond. The maid was

27

Baer, 198.

28

Ibid., 197.

29

Diane Wolfthal. “Foregrounding the Background: Images of Dutch and Flemish Household

Servants.” In Women and Gender in the Early Modern Low Countries, edited by Sarah Joan

Moran and Amanda Pipkin, 217:229–65. Brill, 2019.

http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1163/j.ctvrxk3hp.13., 250.

11

an indispensable part of the Dutch home as she assisted her mistress in multiple daily tasks. In

“Wives and Wantons: Versions of Womanhood in 17th Century Dutch Art”, Simon Schama

points out key details on how the maid would often share meals with her employers, would speak

to them by familiar titles, could sleep in the same room of the children, and would most

importantly be the dresser and confidant to the mistress of the household.

30

In “Vermeer: Consciousness and the Chamber of Being”, Martin Pops notices how the

maid was seen as a sort of accomplice to her mistress.

31

She was often the person who would

hand letters to her mistress that were delivered to the house which was a clear link to the outside

world. Pops states, “The maid (who brings a letter and who will doubtless take one) is a bulwark

of privacy no less than a projection of the explorative spirit, a channel and a barricade.”

32

As

seen in Vermeer’s Lady Writing a Letter with her Maid, the maid is standing as a lookout for

possibly the postman to come and retrieve the letter her mistress is writing. The maid is sharing a

connection with her mistress here that cannot be understated as she is her mistress’ channel to the

world.

However, it is important to consider that the evidence surrounding maids from this time

was not always so positive. In “An Entrance for the Eyes: Space and Meaning in Seventeenth-

Century Dutch Art”, Martha Hollander points out some accounts by visitors to the Netherlands in

Vermeer’s time who were shocked and appalled by many of the maid’s devoted relationships

with their mistresses.

33

She claims that this progressive view of the maidservant is not as

30

Simon Schama. “Wives and Wantons: Versions of Womanhood in 17th Century Dutch Art.”

Oxford Art Journal 3, no. 1 (1980): 5–13. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxartj/3.1.5., 10.

31

Martin Pops. Vermeer : Consciousness and the Chamber of Being. Ann Arbor, Mich: UMI

Research Press, 1984., 80.

32

Ibid., 80.

33

Martha Hollander. “An Entrance for the Eyes : Space and Meaning in Seventeenth-Century

Dutch Art”. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002., 29.

12

favorable in the literature of the Netherlands in the 17th-century.. Hollander mentions, “In the

popular literature of the Dutch themselves, however, this image of the independent servant is

distinctly negative. Both didactic satires and household manuals warn of the maid’s natural

laziness and immorality as threats to the household.”

34

The positive portrayals of maids in art and

more negative depictions in literature create a strong contrast that is visible in Vermeer’s

paintings.

Simon Schama offers an example of more negative depictions from the tales shown

within the book titled, “Zeven Duyvelen Regerende de Hedendaagse DienstMaagden (Seven

Devils Ruling Present Day Serving Maids)” by Simon de Vries, the fourth edition which was

written in 1682, as an example of a negative depiction of maids.

35

It shows maids as “...minions

of the Devil, doing his bidding in seven capacities…” which included breaking objects and

stealing from the home.

36

This negative portrayal in some ways could be related to two of

Vermeer’s paintings, The Love Letter and Mistress and Maid. (Figure 1, c. 1667–1670,

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, Netherlands. Figure 3, c. 1666–1668, Frick Collection, New York,

New York) In both images, the maid has a higher stance than her mistress and has a sly smirk on

her face. She may know what the contents of the respective letters contain as she casts her

knowing look down at her mistress. This link between the two confidants captures fleeting

moments of shared secrecy by Vermeer. It is interesting how some accounts speak to how many

maids could have deep relationships with their mistresses yet others speak of how they could

corrupt their employer. This overall duality between sources speaking on maids in the

34

Hollander, 29.

35

Schama, 10.

36

Ibid.

13

Netherlands is complex and speaks to how interpreting the story behind the maids that appear in

Vermeer’s paintings is highly ambiguous.

Societal Expectations for Middle and Upper-Class Women

Even though the Netherlands’ societal structure in the 17th-century is considered to be

moderately forward-thinking, women were still experiencing the harsh realities of gender

expectations. This mainly pushed middle and upper-class women into running their households

instead of being able to pursue their education. Although there were some opportunities for

women and girls to go to school for their education, certain institutions, like the Latin-focused

academies, were closed to women.

37

They were largely expected to stay home and run the

household if their family or husband was of higher social or class standing. In the Cambridge

Companion to Vermeer, Lisa Vergara states, “Direct participation in politics, institutions of

higher learning, and many economic spheres, for example, were for all practical purposes closed

to women.”

38

It is important to consider that even within some progressive societies like the

Dutch in the Golden Age, there are still areas where women remained at a considerable

disadvantage.

In the middle of the 17th-century, the rising emphasis on domestic virtues and family life

as important parts of society was growing, which differed from previous centuries’ primary focus

on the church or kings.

39

There were defined roles for men and women with the female role

being that of homemaker and the man being the breadwinner. In “Desire and Domestic

Economy”, Elizabeth Alice Honig identifies a poem by Johan van Nyenborch in 1659 and

quotes, “‘And each carries out its work and watches over its affairs,/The women in the house,

37

Peter C. Sutton, Lisa Vergara, and Ann Jensen Adams. Love Letters : Dutch Genre Paintings

in the Age of Vermeer, London: Bruce Museum, 2003., 27.

38

Franits, 55.

39

Wiesman, 7.

14

and the men on the street…’”.

40

Here, there is an outlined separation between the job of a man

and a woman. The men are expected to go out into the world while the women are relegated to

the home. The streets of the cities were seen as a dangerous place for a respectable, high class

woman, so many Dutch art patrons wanted to own paintings that depicted scenes of “safe”

domestic virtue as seen in Vermeer’s work. In his painting The Love Letter, the mistress is seen

taking a break from her domestic chores, noticeable by the broom placed by the doorframe and

the laundry basket sitting next to her. (Figure 1, c. 1669 - c. 1670, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam,

Netherlands) In her time, this woman would be confined to her home because if she were to

venture outside very often, her supposed pure nature was at risk. Honig also discloses, “With the

public world clearly defined as a danger zone, the woman who enters into it bears the

responsibility of laying herself open to public scrutiny.”

41

The domestic home was culturally

seen as a private zone where the woman could refine her domesticability. As long as she mainly

resided within her safe area, her virtue was protected.

Education

The women in Vermeer’s paintings must be educated since they are clearly displaying

their ability to read or write letters. The Netherlands was considered to be the most literate single

population in all of Europe in the 17th-century.

42

In 1603, a visitor to the country and one of the

continent’s most well-known scholars at the time, Joseph Scaliger, remarked that in the country,

even poorer women and women, often many of the maids, could effectively read and write.

43

With the turn of the 17th-century, the Dutch had advanced systems for early and secondary

40

Elizabeth Alice Honig. “Desire and Domestic Economy.” The Art Bulletin (New York, N.Y.)

83, no. 2 (2001): 294–315. https://doi.org/10.2307/3177210., 306.

41

Honig, 307.

42

Helmers, 333.

43

Ibid.

15

education. There were private schools that may have been for upper-classchildren that had

classes in foreign languages, mathematics, navigation for sailing, bookkeeping, and sewing

which were reserved for young girls.

44

Some of these private schools were run by women for

girls and were aimed at primarily learning how to read and write.

45

Overall, with the attention the

Golden Age placed on literature and writing, education grew at an accelerated pace.

Letters and Epistolary Culture

As a result of an increased focus on education and schooling, the Dutch epistolary culture

began to thrive in the Golden Age. Before the 17th-century, letters were used primarily as

correspondence for official government, commerce, trade, and business matters. Within this

time, letter writing as a way of communicating highly personal affairs was swept into the

Netherlands as a result of higher levels of literacy in the population. The skill of having the

ability to write a letter was understood as a definitive indicator of an educated man or woman

who possessed class and proper etiquette.

46

In Marjorie E. Wieseman’s “Vermeer’s Women:

Secrets and Silence”, this scholar pays close attention to the letter-writing practice and notes

how, “Expressions of polite regard and ardent passion, and the acceptance or rejection of these

sentiments, were all addressed in elegantly ritualized prose.”

47

If a woman, like those in

Vermeer’s paintings, was able to read and write, she could create an outlet for herself in which

she could link herself to the various realms of Dutch society.

Such massive volumes of letters coming into and out of the respective cities are

somewhat thanks to the soaring levels of trade and publishing fields that permitted high levels of

traffic. The Dutch had a sophisticated postal system complete with many cities having official

44

Ibid., 337.

45

Ibid., 337.

46

Wieseman, 49.

47

Ibid.

16

“postmasters” that would oversee the delivery of the mail.

48

In a way, the Dutch population of

the 17th-century has documented their own history in their own words through their surviving

letters.

49

In “Love Letters: Dutch Genre Painting in the Age of Vermeer” Peter C. Sutton notes,

“...the history of the Dutch Golden Age can often best be appreciated and recaptured by the

eyewitness accounts of professional and personal letters.”

50

The Dutch truly did unknowingly

preserve their stories through their own eyes.

51

Ultimately, the country’s fondness for epistolary

past-times overall communicates a highly sophisticated and educated society.

Epistolary Guidebooks

The women in Vermeer’s paintings could easily be either reading a letter addressed to

them that was copied from a guidebook or emulating one of those sample letters themselves.

Epistolary manuals and guidebooks had sample letters for any and every type of correspondence

that people could desire and comprised some of the most popular reading materials of the time.

52

The guidebooks included letters of condolence, sadness, regret, passion, and most commonly,

letters for lovers to use while engaged in a courtship.

53

Sample love letters include the themes of

the distance between lovers and a man’s fear that his lover will lose passion for him while he is

away working.

54

It is quite contradictory how letters were considered to be highly personal and

private, yet the manuals provided word-for-word example letters that removed some sense of

uniqueness since they could often be copied exactly like the way they were written in the books.

48

Ibid., 29.

49

Sutton, 15.

50

Ibid.

51

Ibid., 14.

52

Franits, 103.

53

Wieseman, 49.

54

Franits, 105.

17

This could mean that people could possibly assume what might be written in other people’s

letters, especially if they were love letters.

One of the popular guidebooks, as noted by Peter C. Sutton, is “Love Letters: Dutch

Genre Painting in the Age of Vermeer, was Puget de la Serre’s La Secrétaire à la mode.

55

Sutton

describes how this manual had many examples of love letters with varying responses to go along

with them.

56

Sutton’s excerpts from these letters by the suitors include, “‘I must of necessity for

my own Quiet declare the desire which I have, to love, and to serve you, if you Judge mee

worthy of so great an honour’” and “‘I should not take the Liberty to let you know how

extremely I honour you, if the Absolute power of your Beauty did not force me to it.’”

57

Sutton

describes one of the lady’s responses as, “‘I am much obliged to you for the good will you

witness in my behalfe, but I have no other Liberty left mee, except to give you thanks as I do

very humbly: assuring you that I will conserve your Remembrance for an acknowledgment.’”

58

It

is harmless to assume with this knowledge that the women in Vermeer’s letter paintings may be

writing or reading something that resembles these examples. Sutton finally states, “All of these

personae subsequently enter into exchanges that alternate in varying degrees between passion

and high anxiety.”

59

The guidebooks truly had responses and declarations for any and all

occasions, furthering their own popularity.

Domesticity and Genre Paintings

During Vermeer’s prime, genre paintings, which are domestic scenes and narratives of

everyday life, were rising in popularity.

60

These paintings of often quiet, simple scenes of

55

Sutton, 35.

56

Ibid.

57

Ibid.

58

Sutton, 35.

59

Ibid., 36.

60

Franits, 286.

18

domestic duties are exactly what is depicted in his paintings of women and letters. The rise of

this kind of painting called for depictions of family virtues and an overall focus on “household

cleanliness” and the privacy of the home as outlined by Marjorie E. Wieseman which was a

central part of Dutch culture in the Golden Age.

61

Simon Schama points out how, “...the most

successful genre paintings are two-way mirrors reflecting the outer world of polite or impolite

behavior, and the inner world of doubt and apprehension.”

62

This is an important detail to keep in

mind because most genre paintings depict the idealities of Dutch home life. These images

commonly showed scenes where the subject was constructed within a clean home, easily

completing a task, showing people the level of domesticity that they should strive to achieve.

However, the paintings did not always show a clear and truthful version of reality. Helmer J.

Helmers notes, “...they synthesize observed fact with a well-established repertoire of motifs and

styles to create what are, in essence, fabricated images.”

63

This view of genre paintings as

“fabricated” gives viewers a different point of view regarding the genre scenes not as definitive,

fully truthful paintings but as captured moments of the aesthetic views of Dutch culture.

64

At this time, Dutch home life was beginning to transition into a space where there was

more privacy and seclusion than in previous years before the mid 17th-century or so.

65

Helmer J.

Helmers describes these changes and states, “...the tremendous demand for paintings of

domesticity coincided with changing patterns of house construction that distinguished the public

from what were, at that time, rather novel private spaces.”

66

It was a shift in the public’s view of

the home where the distinction between common life and family life was becoming more

61

Wieseman, 7.

62

Schama, 13.

63

Helmers, 269.

64

Ibid., 286.

65

Ibid., 283.

66

Ibid.

19

separate. In “Picturing Men and Women in the Dutch Golden Age” authors Klaske Muizelaar

and Derek L. Phillips brings to light how, “A family’s home was a territory with restricted

access, and the use of specific spaces reflected the relationships among both its inhabitants and

men and women from outside.”

67

Similarly, Helmer J. Helmers also emphasizes how rooms were

changing in their purpose in Vermeer’s age, where the rising need for separate private spaces

was gaining in popularity. In “An Entrance for the Eyes: Space and Meaning in Seventeenth-

Century Dutch Art”, Martha Hollander outlines what the home meant for the Dutch and

discloses, “What did the house signify in Dutch society? It expressed both public display and

private withdrawal, the benefit of worldly achievement and the arena of familial harmony.”

68

She

emphasizes the common thread of the, “...theme of quiet retreat…” where specifically women

could find solace and privacy within their home.

69

One can notice this theme in all of Vermeer’s

paintings of women and letters, but it stands out in those of a solitary woman.

Woman in Blue Reading a Letter

One of Vermeer’s paintings that captures the images of the stillness of reading, the absent

lover, and the map on the wall is Woman in Blue Reading a Letter (Figure 2, c. 1662–1665,

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, Netherlands). Here, one can almost grasp the feeling of the woman

holding her breath as she holds her letter close to her heart in the privacy of her own home. The

closeness to her chest with which she holds the letter along with her firm handle on it suggests a

full dedication to reading. She is holding the letter near the top of it so it gives the impression

that she has just begun to read. Vermeer painted her to appear unaware of the viewer, as evident

67

Klaske Muizelaar, and Derek L. Phillips. “Picturing Men and Women in the Dutch Golden

Age : Paintings and People in Historical Perspective”. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2003.,

37.

68

Hollander, 177.

69

Hollander, 178.

20

by her calm demeanor in knowing she is alone in private. She is fully unconcerned or unaware

that the viewer is watching her and her focus is completely steady as she takes in the message

she has received. Jane Jelley describes her as she is, “...sounding the slow words in her head;

bracing her body for the news the missive might bring…”.

70

It is a feeling of anticipation for the

emotion that the letter will surely deliver to her. Marjorie E.Wieseman also focuses on how the

woman has been disrupted at her toilet where she must have been readying herself for the day.

71

With the emotion she felt with the delivery of the letter, she stood up to read which demonstrates

the apprehension and uncertainty she feels in discovering the letter’s elements.

Norbert Schneider brings up the chance that the woman could be Catharina Bolnes,

Vermeer’s wife.

72

He also mentions the fact that some scholars believe she may be pregnant

since she had multiple pregnancies throughout her marriage to Vermeer.

73

Schneider considers

the theory that if she is truly pregnant, her reading the letter is a “moral contradiction of the

respectability of marriage”.

74

It is likely that love letters were mostly exchanged between those

engaged in a courtship or extramarital affair instead of a couple who was already married. So, if

it is a love letter and if she is pregnant, she is actively going against the culture of the time that

considered pregnancy outside of marriage an atrocity.

75

With this in mind, her lover is clearly not

with her since she is reading a letter from him. This theme of the distance between lovers was

very common in love letter manuals.

76

Peter C. Sutton offers a sample from a period love letter

example where the man says, “I passe over whole daies without eating, and whole Nights

70

Jelley, 150.

71

Wieseman, 112.

72

Norbert Schneider, and Johannes Vermeer. Vermeer, 1632-1675 : Veiled Emotions. Kln:

Taschen, 2000., 49.

73

Schneider, 49.

74

Ibid.

75

Ibid.

76

Sutton, 36.

21

without sleep…Judge now if I be not one of the most wretched Lovers in the World. Yet my

consolation is this, that I suffer all these Afflictions for the most worthy subject living, and for

whom I would lose a Thousand lives.”

77

The man is fully distraught without his love as he writes

down his feelings on paper for his far away lover to read.

Another detail that Vermeer painted within the composition that provides clues into her

absent lover and the outer world is the map that is hanging on the wall behind the woman. Maps

were commonly used in Dutch genre paintings as decorative items with often symbolic meanings

behind them as Martha Hollander writes in “Public and Private Life in the Art of Pieter de

Hooch”. She writes, “Maps were another popular feature of household décor, and they frequently

appear in domestic scenes as allusions to a larger context beyond the city, bringing the outside

world into the house. They appear variously as symbols of worldly vanity or topical references to

political conditions in the Dutch Republic.”

78

Maps were also a visual connection to the success

of the Dutch Global Trade industry, hinting at the successes that the Golden Age brought to the

Netherlands. In this particular painting, the map is a symbol that stands for the subject’s link to

the outside world coming into her home. Here, the woman is a quiet, stoic figure that is yearning

to be reunited with her lover while her only link to him is the map on the wall and the letter she

holds in her hands. It is the ambiguity of her story that grasps viewers’ attention in the same

sense as she is engaged with her letter.

Mistress and Maid

77

Ibid.

78

Martha Hollander. “Public and Private Life in the Art of Pieter de Hooch.” Nederlands

Kunsthistorisch Jaarboek (NKJ) / Netherlands Yearbook for History of Art 51 (2000): 272–93.

http://www.jstor.org/stable/24706499.

, 289.

22

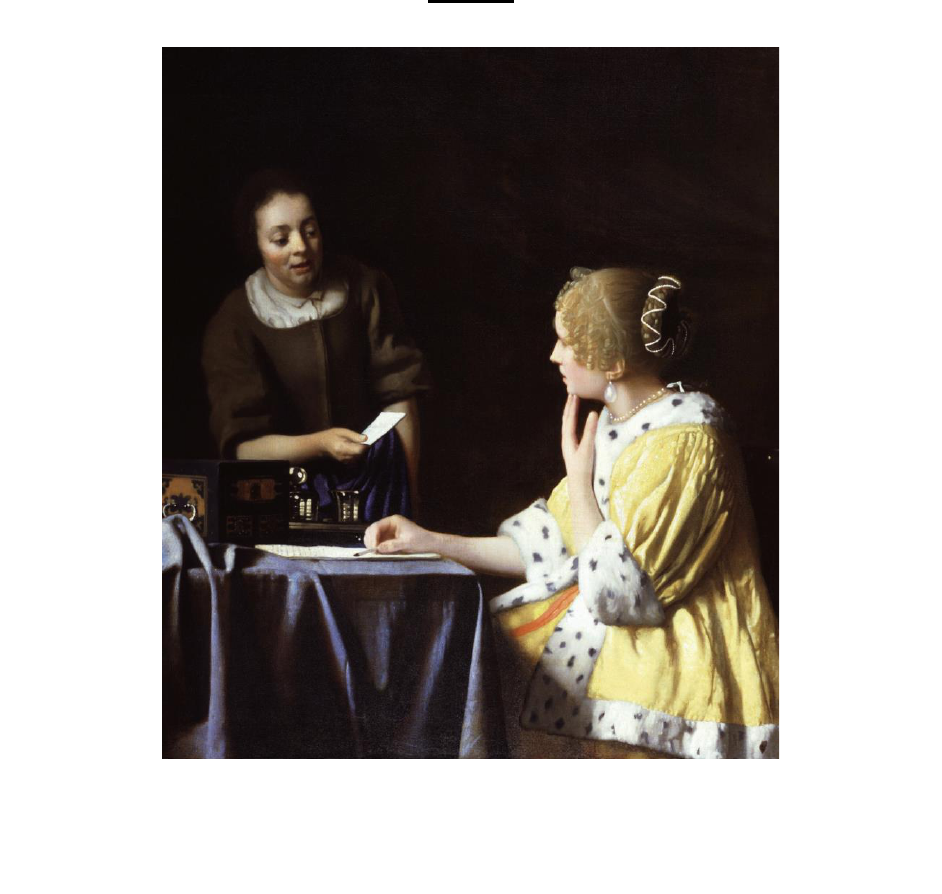

The next painting, Mistress and Maid, captures an exchange between a mistress and her

maid as the servant hands her lady a letter that has just been delivered to the household. (Figure

3, c. 1666-1668, Frick Collection, New York) This work stands out among Vermeer’s five other

letter paintings because the woman is being handed a new letter while she is already writing a

response to a different letter. The delivery of the letter seems like a surprise to the woman as she

holds her hand near her face in confusion or shock. Norbert Schneider points out how the

woman, “...who has just written a few lines, is obviously hesitant to accept it. It seems to throw

her into confusion, and she is beginning to have scruples about whether she should let herself in

on this adventure or not”.

79

She is caught in the moment of deciding what her next step will be.

Overall, it is an overwhelming feeling of uneasiness that exudes from the picture. Vermeer hones

in on this moment of emotion by cropping in the picture very closely so that only the pair of

women is in view and the rest of their surroundings are covered in dark shadows. He illuminates

the mistress, wearing an elaborately fur-lined and bright yellow dress, in a wash of softly lit,

white light. On the other hand, the maid is shadowed in the darkness and only just seems to be

emerging from the depths of the room with her hand reaching out. The contrast between the

lighting of the two women suggests a complementary pair of light and dark. Here, they are

working in tandem as a pair through their shared knowledge of the letter.

Norbert Schneider suggests, “It may be that what she is writing in her own letter, and the

content of the message that she has yet to read, are at odds.”

80

This diversion between the two

letters implies multiple lovers, as identified by Rodney Nevitt Jr.

81

The maid seems to be in on

her mistress’ little scandalous secret. Schneider states, “She is acting as a silent go-between, and

79

Schneider, 51.

80

Schneider, 51.

81

Franits, 104.

23

enjoys the confidence of her mistress.”

82

In “Mistress and Maid”, Margaret Iacono notices how

the addition of a second subject in the painting contributes a second level of intricacy to the

theme of maids.

83

She is not just on her own here, she specifically has a role where she is truly

the “go-between”.

84

It is the connection between the two women that is the sole focus of this

painting. Her mistress must have a great deal of trust in her maid if she is confident in letting her

servant in on her slightly secret affair. This connects to how many Dutch women were known to

have deep relationships with their maids, as discussed by Simon Schama in “Wives and

Wantons: Versions of Womanhood in 17th Century Dutch Art”.

85

One other possible story here

is how the maid could be corrupting her mistress by suggesting she continue with an affair of

sorts like how Schama also describes the contrast and says, “If then, the housewife role

represented the incarnation of vigilant virtue in women, the maid was held to incarnate the

opposing qualities: sin and corruption.”

86

There is a chance that this maid might be introducing

her housewife to her own nefarious ways, as emphasized by the higher stance she has over her

mistress who is seated below her maid.

Rodney Nevitt Jr. describes how many of Vermeer’s maids he depicts in his letter

paintings would not be common household servants like one that is depicted in his famous

Milkmaid painting.

87

(Figure 6, c. 1660, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, Netherlands) He says that

these maids would most commonly be “Kameniers” or ladies maids that were at the side of their

mistresses each day.

88

These kinds of maids were strictly focused on keeping their mistress’

82

Schneider, 51.

83

Margaret Iacono, and James Ivory. Vermeer’s Mistress and Maid. New York: The Frick

Collection, 2018., 34.

84

Schneider, 51.

85

Schama, 10.

86

Schama, 10.

87

Franits, 105.

88

Ibid.

24

private affairs separate from public knowledge.

89

He also states how some sources from the

period describe wives planning secret agendas with their maids. Nevitt Jr. describes how young

men trying to court women were heartened to become close to their lover’s maids so that they

could exchange secret letters or communicate through the “Kameniers”.

90

Lastly, the scholar

identifies an example of how in Jacob Westerbaen’s “Avondschool”, he suggests that young

women utilize the secret nature of maids and says, “‘Even if you are closely watched, you will

find the chance/ To communicate your vrijer through your maid./ You will have the chance to

write back and forth./ Your little letters will go forth, and all remain hidden.’”

91

It is the moment

of exchange that one can witness here through the artist’s exquisite capture of a private moment.

Ultimately, Vermeer depicts this maid and mistress relationship through visual clues that

strongly emphasize the two women as they carry out their roles in furthering this secret affair

through letters. Here, the maid is a physical courier of secrecy.

Lady Writing a Letter with her Maid

The third painting, Lady Writing a Letter with her Maid, exemplifies the theme of female

literacy along with a moment where the maid occupies the center portion of the composition.

(Figure 4, c.1670–1671, Frick Collection, New York) This work is an ideal example of how, as

Rodney Nevitt Jr. says, Vermeer leaves it to the viewer to reconstruct the story. One must

assemble the various puzzle pieces of visual clues to gain a glance into the lady’s letter. The first

visual clues lie in the maid herself. While the mistress writes a letter, the maid is firmly standing

by the window. However, in this painting the maid is more than her mistress’ confidant as she is

completely centered in the middle of the work. One can almost feel her daydreaming about the

89

Ibid.

90

Franits, 105.

91

Ibid., 106.

25

streets beyond the walls of her mistress’ home. The viewer’s eye is drawn directly to her as her

face is fully lit up with light. Whether she is either waiting on her lady to finish her letter so she

may deliver it to the postman or daydreaming about her own private life as she stares out the

window, one does not know. Rodney Nevitt Jr. asserts “...her gaze underscores the charged

relationship between the interior, the private audience with her mistress, and the outside world,

from which the letter has come and to which another will be sent.”

92

If the maid was not included

in this scene, the impact would be much different and one would find that the focus would fall

more on the mistress’ act of writing the letter. In speaking on the maid’s role, Martin Pops states,

“...she is caught in the ambiguity of standing back and going forth, and therein lies the drama of

the painting.”

93

The maid is the main physical link through which her mistress communicates to

the external world beyond her home. She is truly a “Kamenier” as she physically stands between

her mistress and the window, waiting for the chance to defend her mistress’ dignity and

privacy.

94

There are three visual elements within this scene that, once discovered, reveal

possibilities on what the story could be. The first symbol is the painting on the wall behind the

mistress. This painting departs from the usual imagery of a stormy sea that consistently appears

in other Dutch genre paintings. An example of another genre painting depicting this imagery is

Gabriel Metsu’s Woman Reading a Letter. (Figure 7 c. 1664-1666, The National Gallery of

Ireland, Dublin, Ireland) In this image, the maid pulls back a curtain that covers the painting on

the wall and reveals the picture to either the viewer or her mistress. Vermeer's painting on the

wall in this image departs from this norm and depicts the scene of “The Finding of Moses”,

92

Franits, 105.

93

Pops, 84.

94

Franits, 105.

26

where the pharaoh's daughter discovers the infant Moses in a basket in the river.

95

Nevitt Jr.

notices how the pharaoh's daughter holding Moses perfectly lines up with the mistress seated at

the table.

96

While he believes it could be a clue as to how the letter may refer to delivering or

receiving an item of large importance, such as a baby in the biblical tale, Norbert Schneider

regards the painting as referring to the abandonment of a child from a secret love affair.

97

He

states that it was a common practice for women who had “illegitimate” offspring in the 17th-

century and says, “The very high number of paintings that deal with extramarital relations show

that it was difficult to impose proper monogamous behavior from above.”

98

This understanding

connects back to the societal expectations for women at this time where they were expected to be

completely chaste unless they were married. Yet another example of how middle and upper-class

women were largely cornered into running their homes indoors.

In “Picturing Men and Women in the Dutch Golden Age” Klaske Muizelaar expresses,

“More than anything else, a woman’s honor and respectability rested on her sexual behavior:

virginity was expected of the unmarried, fidelity of the married.”

99

Domestic duties and societal

“respectability” ruled over women. The secret child from a love affair would be a bombshell in

Dutch society at the time. The maid might be keeping watch to protect the scandalous letter from

leaking. Since love letters were seen as legal evidence, the danger of the possible secret being

leaked would be a travesty to the women. Schnieder says, “The contemporary literature of

jurisprudence declared that litterae amatoriaei (on which dissertations were written) were a

proper subject of legal inquiry. The lawyers would aim to determine whether such letters implied

95

Franits, 106.

96

Ibid.

97

Schneider, 54.

98

Ibid.

99

Muizelaar, 7.

27

a promise of marriage or (if one correspondent was already married) adultery.”

100

If the letter

truly contained such details, the maid could be a lookout and protector of her mistress’ secret so

that no one would dare get a chance to find out what the lady was writing in her letter.

The next motif is the crumpled piece of paper or letter lying on the floor in front of the

table in the foreground along with some sealing wax and a red letter seal.

101

(Figure 8) While the

National Gallery of Ireland’s wall label alongside the painting describes the object as a letter-

writing manual, it would explain why it was crumpled if it were a letter that upset the mistress.

102

If it was a manual, it would most likely not be crumpled on the floor. Also, there is some

source material from the 17th-century that tells a story about how a woman received a letter and

was upset with the contents so she threw it on the floor. Rodney Nevitt Jr. identifies the story

from the collection called, “De wonderlijke vryagien, en rampzalig, doch bly-eyndige, trouw-

gevallen van deze tijdt…voorgevalle in hett roem-ruchlitgh Hollandt (The Wondrous Courtships

and Betrothals of This Time…Both Disastrous and Happy, Occurring in the Famous

Holland).”

103

He describes how the character Leliana received a letter that she thought was from

her love when it was really from another man. Nevitt Jr. says, “‘...but having opened [the letter],

and seeing at the bottom the name of Kandoris, [she] became as angry as she had once appeared

happy, and without looking at it further, threw it on the floor without casting the slightest glance

at it.’”

104

Although Vermeer painted such a quiet, silent scene in this painting, one can see how the

woman might have been upset with the letter’s contents like Leliana and sat down to write her

100

Schnieder, 54.

101

Franits, 106.

102

Wall text, Woman Writing a Letter, with her Maid, NGI.4535, National Gallery of Ireland,

Dublin, Ireland.

103

Franits, 106.

104

Ibid.

28

response. In “Vermeer and the Masters of Genre Painting”, Adriaan E. Waiboer claims that

Vermeer was inspired to paint such a motif in the foreground because he was influenced by

Gerard ter Borch’s painting, Officer Writing a Letter, with a Trumpeter. (Figure 9, c. 1658-1659,

Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania). Within this picture, there is a broken

pipe and a playing card with the ace of hearts on it that hints at the officer writing a love letter.

105

This style of painting, leaving symbols in the foreground, leaves the hint directly in the eye line

of the viewer so it is possible that Vermeer was influenced by Ter Borch. Vermeer departs from

Ter Borch’s depiction by painting a pair of women instead of men, which shows an alternate take

on the representation of letter writing.

The final motif that Vermeer included is the mistress herself. In “Vermeer’s Women:

Secrets and Silence”, Marjorie E. Wieseman highlights this imagery and notes that the woman is

displaying the theme or example of “feminine virtue”.

106

This virtue, or her literacy and

intelligence, is ideally pictured as she is focused on her task. The woman’s arms form a perfect

triangle with the top of her head in a way that emphasizes her stability at the table. Here, she is

posed in a way that was more commonly reserved for men or the pose of the male academic at

his desk.

107

Wieseman says, “Vermeer takes the often-seductive address to the viewer and gives

it intelligence and substance, in part, by appropriating the pose of the scholar at his desk, a

pictorial type that heretofore had been used exclusively for men.”

108

Here, Vermeer throws a spin

on the classic stance of the male scholar and challenges it by placing his female subject in the

105

Adriaan E. Waiboer, Arthur K. Wheelock, Blaise Ducos, Piet Bakker, Quentin Buvelot, E.

Melanie Gifford, Lisha Deming Glinsman, Marjorie E. Wieseman, Eric Jan Sluijter, and Eddy

Schavemaker. Vermeer and the Masters of Genre Painting : Inspiration and Rivalry. Dublin:

National Gallery of Ireland, 2017., 121.

106

Wieseman, 112.

107

Ibid.

108

Ibid.

29

same view. One could compare the pose of this woman to that of the male subject in Gabriel

Metsu’s Man Writing a Letter. (Figure 10, c. 1664-1666, National Gallery of Ireland, Dublin,

Ireland). The focus and the way the man is resting his arms on the table are mirrored in

Vermeer’s composition. This comparison gives Vermeer’s painting another potential meaning,

specifically that of an educated, literate woman fully capable of writing a response to her lover

within her letter. Primarily, she is seen as an intelligent woman as she crafting the perfect words

to send to her secret lover.

Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window

The final painting, Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window, is unique due to its

legitimately hidden secret and unique composition. (Figure 5, c. 1657-1659, Gemäldegalerie Alte

Meister (Old Masters Picture Gallery), Dresden, Germany) The young woman is situated directly

next to the open frame of a window as she reads her letter while her reflection is mirrored on the

glass next to her. The open window could refer to her lover who is away from whom she is

connected by the open window. In “Vermeer’s Hat: The Seventeenth Century and the Dawn of

the Global World”, Timothy Brook says, “The man is out there somewhere, able to speak to her

only through letters.”

109

While he is away in some unknown land, she is painted specifically

within the confines of her home. The open window also connects to the outer world which, in

Dutch society at the time, was mainly seen as only safe for men.

110

Martha Hollander outlines in

“Public and Private Life in the Art of Pieter de Hooch”, how “Scenes of women writing, reading

or receiving letters often include references to the outside ‘masculine’ world from which the

letter comes. These take the form of pictures on the walls such as maps, seascapes, landscapes, or

109

Brook, 54.

110

Honig, 307.

30

views from windows.”

111

This woman holds in her hand the only way she has to communicate

with her lover as she stands in front of the only link she has to him, the open window.

The unsure expression she bears conveys an emotion that is quite subtle as she stares

down at the paper in her hands. She is tightly grasping the bottom of the letter as she reads while

holding it relatively far from her face. The fact that her face shows deep engagement yet she is

grasping the letter far down on the paper could allude to how she is trying to restrain her

emotions so that no one will see what she is feeling. This need for privacy resembles a passage

from a story written on by Rodney Nevitt Jr. in “The Cambridge Companion to Vermeer”. He

describes a passage from “De hoofse Clitie” where the character Clitie has just received a letter

and rushes off into privacy to open it. It says,

Clitie, finding herself alone, took it [the letter], an – having stuck it in her bosom – went

to a private room. O lucky Paper, though without feeling, can you not feel, and though

without eyes can you not see, and though without lips can you not kiss this beautiful

bosom? Cleaner, fear not that your letter was lost…. Before she opened it, she kissed it,

and signed at every word as she read it. And her signs called forth tears…

112

The emphasis on leaving to go to a “private room” emphasizes the need for separation from the

public sphere when opening a letter because of the emotional effect it has on the reader, as seen

here by Clitie’s tears.

113

Another element that contributes to the air of privacy and seclusion the

painting possesses is the curtain that is drawn over a fourth of the painting. Curtains like this one

were often hung over paintings in the 17th-century to protect them from dirt or dust, as noticed

by Rodney Nevitt Jr.

114

This scholar also states that curtains were hung on windows inside Dutch

homes to separate one room from another as seen in Pieter de Hooch’s painting, The Bedroom.

115

111

Hollander, 284.

112

Franits, 106.

113

Ibid.

114

Ibid., 110.

115

Ibid.

31

(Figure 11, c. 1658-1660, the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.) Whether the curtain in

Vermeer’s painting is supposed to be seen as part of the painting itself, simply in the room with

the painting, or if it is just a protective curtain, is unclear.

116

Regardless, the curtain is standing as

a signifier of privacy which could be drawn to block the viewer from taking another glance. At

any moment, the viewer’s viewpoint could be hastily drawn away by the glide of a curtain across

the painting.

One final clue that Vermeer left behind is that of the bowl of fruit on the table. Norbert

Schneider emphasizes this detail and connects it to a hint at an extramarital relationship.

117

He

tells readers, “The bowl of fruit in Vermeer’s Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window, which

is lying on the folds of the table rug, is a symbol of extramarital relations, which broke the vow

of chastity. Such a relationship is being planned or continued by means of this letter, and the

apples and peaches are intended to remind us of Eve’s transgression.”

118

The relation to the story

of Adam and Eve by Schneider clues into a possible story of betrayal, since Eve was largely

blamed over Adam for betraying God. This could mean that the woman is betraying her spouse

in an affair. The visibility of where Vermeer places the fruit is key. It has a central part in the

painting highlighted with bright light. If the woman was engaged in an extramarital relationship

like Schneider states, the window might be her only route to channel her lover. It is possible that

when she received the letter, she dashed off to read it like Clitie from“De hoofse Clitie” while

maybe her husband potentially presided in another room of the house, oblivious to his wife’s

betrayal.

119

Then, the curtain would be the only way the woman could hide her little secret from

prying eyes.

116

Schneider, 49.

117

Schneider, 49.

118

Ibid.

119

Franits, 106.

32

Lastly, one of the most interesting parts of this artwork was revealed recently when a

painting of Cupid was unsurfaced from beyond layers of paint on the surface of the upper part of

the work.

120

Experts have been said to have known about the Cupid painting ever since an X-Ray

was conducted in 1979.

121

However, the painting within the painting was fully uncovered

recently, after a quest to restore the painting was begun in 2017.

122

The big question of whether

or not Vermeer painted over the cupid himself or if another artist did at a later date remains.

Some claim that another artist hid the cupid, but others still firmly believe it was Vermeer

himself. If the artist covered up his work, it would be a clear indication that he was purposefully

attempting to elude viewers of another clue that would signal the contents of the letter, since

Cupid is commonly tied to the theme of love. In “An Entrance for the Eyes: Space and Meaning

in Seventeenth-Century Dutch Art”, Martha Hollander points out how Vermeer has been known

to cover up his craft. She claims, “With his characteristic tendency toward revision and

reduction, Vermeer frequently eliminated motifs already fully painted.”

123

Another example of a hidden image is how Vermeer covered up the appearance of a dog

and a man in the backroom area of his painting, A Maid Asleep, with a chair and a mirror.

124

(Figure 12, c. 1656-1657, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, New York.) Hollander also

says, “...Vermeer tended to empty out his pictures progressively, subduing their symbolic

references.”

125

This is a definitive example of how Vermeer eliminated clues and visual details in

120

Tessa Solomon, “Restoration of Vermeer Painting in Germany Reveals Hidden Image of

Cupid”, artnews.com, ARTnews, August 24, 2021. https://www.artnews.com/art-

news/news/vermeer-girl-reading-a-letter-cupid-restoration-1234602227/.

121

Tessa Solomon, “Restoration of Vermeer Painting in Germany Reveals Hidden Image of

Cupid”, artnews.com, ARTnews, August 24, 2021. https://www.artnews.com/art-

news/news/vermeer-girl-reading-a-letter-cupid-restoration-1234602227/.

122

Ibid.

123

Hollander, 98.

124

Ibid.

125

Ibid.

33

his artworks to remove the simplicity through which the works could be understood. He actively

chose to make his painting A Maid Asleep more ambiguous, so it is possible that he may have

done that with Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window. (Figure 12, Figure 6) In essence, the

unveiling of the artist’s Cupid imagery is a distinct clue to how Vermeer may have wanted to

make his composition more enigmatic. Without the revelation of the painting of the Cupid, the

little god would have remained Vermeer’s secret for years to come.

Conclusion

It seems as if one has entered a different dimension when viewing a Johannes Vermeer

painting. Each artwork possesses an intangible quality that is otherworldly and enigmatic while

the mysteries his paintings hide hold both unambiguous stories and hidden secrets. There is a

feeling of sheer suspense born from studying Vermeer’s women and letters paintings, as

Marjorie E. Wieseman describes, “In painting as well, the secrecy and withholding of content

inherent in written communication invested narratives with tension and ambiguity.”

126

This

“tension” is utterly tangible through the scenes at play in the artist’s composition. One feels a

deep concentration within the quest to discern the Dutch painter’s hundreds of years-old

mysteries. Through an understanding and appreciation of key details from the history of the

Dutch Golden Age, the secrets of these paintings are available for closer study. From the various

backgrounds and contexts described in this paper, viewers can begin to understand the historical

basis for these works which can help to unlock some of Vermeer’s artistic choices. By focusing

on elements Vermeer created such as the paintings inside the paintings, visual clues and imagery,

the placement of the respective women, and the interplay between maids and mistresses, endless

narratives may arise.

126

Wieseman, 50.

34

At first glance, the subject matter of each one of these four paintings, Woman in Blue

Reading a Letter, Mistress and Maid, Lady Writing a Letter with her Maid, and Girl at an Open

Window Reading a Letter, appears simple and calm. (Figures 2, 3, 4, 5) However, once the

viewer deciphers the traces Vermeer paints across his canvases, innumerable and imaginative

explanations can allude to often scandalous, intense affairs. Whether the story is that of a secret,

extramarital love affair, the relationship between a maid and her mistress, a maid protecting her

mistress’ privacy, or once undisclosed imagery hinting at love, Vermeer leaves the door open for

continual interpretation. In “Traces of Vermeer'', Jane Jelly asserts, “We have climbed through

his looking glass, where the rules are not the same as in our own universe. The world in here is

freeze-frame and attractively soft and blurred. It is its lack of focus, which makes us want to

move into his spaces to find more detail, but no matter how hard we try, we can never get close

enough.”

127

It is here, in these paintings of women and letters, that the delicate, dream-like gazes

from the women capture the viewer and refuse to let go, pulling the viewer deeper into the

paintings all while keeping one at a perfect distance, far-away from discovering their mystifying

secrets.

Figure 1

127

Jelley, 171.

36

Johannes Vermeer, Woman in Blue Reading a Letter, c. 1662–1665, Oil on canvas, 46.5 x 39

cm., Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, Netherlands.

37

Figure 3

Johannes Vermeer, Mistress and Maid, c. 1666–1668, Oil on canvas, 90.2 x 78.7 cm., Frick

Collection, New York, New York.

39

Figure 5

Johannes Vermeer, Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window, c. 1657–1659, Oil on canvas, 83 x

64.5 cm., Old Masters Picture Gallery, Dresden, Germany.

40

Figure 6

Johannes Vermeer, Milkmaid, Oil on canvas, c. 1660, 45.5 x 41 cm, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam,

Netherlands.

41

Figure 7

Gabriel Metsu, Woman Reading a Letter, c. 1664-1666, Oil on wood panel, 52.5 x 40.2 cm,

National Gallery of Ireland, Dublin, Ireland.

42

Figure 8

Detail, Woman Writing a Letter, with her Maid, Oil on canvas, c. 1670, 71.1 x 60.5 cm, National

Gallery of Ireland, Dublin, Ireland.

43

Figure 9

Gerard ter Borch the younger, Officer Writing a Letter, with a Trumpeter, Oil on canvas, c.

1658-1659, 56.8 x 43.8 cm, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

44

Figure 10

Gabriel Metsu, Man Writing a Letter. Date: 1664-1666. Oil on wood panel, 52.5 x 40.2 cm.

National Gallery of Ireland, Dublin, Ireland.

45

Figure 11

Pieter de Hooch, The Bedroom, c. 1658-1660, oil on canvas, 51 x 60 cm, the National Gallery of

Art, Washington, D.C.

46

Figure 12

Johannes Vermeer, A Maid Asleep, c. 1656-1657, oil on canvas, 87.6 x 76.5 cm, The

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, New York.

47

Bibliography

Baer, Ronni, Henk F. K. van. Nierop, Herman. Roodenburg, Eric Jan Sluijter, Marieke de.

Winkel, Sanny de Zoete, and Diane Webb. Class Distinctions : Dutch Painting in the Age

of Rembrandt and Vermeer. First edition. Boston: MFA Publications, Museum of Fine

Arts, Boston, 2015.

Brook, Timothy. Vermeer’s Hat : the Seventeenth Century and the Dawn of the Global World.

1st

U.S. ed. New York: Bloomsbury Press, 2008.

Franits, Wayne E. The Cambridge Companion to Vermeer. Cambridge ;: Cambridge University

Press, 2001.

Helmers, Helmer J., and Geert H. Janssen. The Cambridge Companion to the Dutch Golden Age.

First edition. Cambridge ;: Cambridge University Press, 2018.

Hollander, Martha. “An Entrance for the Eyes : Space and Meaning in Seventeenth-Century

Dutch Art”. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002.

Hollander, Martha. “Public and Private Life in the Art of Pieter de Hooch.” Nederlands

Kunsthistorisch Jaarboek (NKJ) / Netherlands Yearbook for History of Art 51 (2000):

272–93. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24706499.

Honig, Elizabeth Alice. “Desire and Domestic Economy.” The Art Bulletin (New York, N.Y.)

83,

no. 2 (2001): 294–315. https://doi.org/10.2307/3177210.

Iacono, Margaret, and James Ivory. Vermeer’s Mistress and Maid. New York: The Frick

Collection, 2018.

Jelley, Jane. Traces of Vermeer. First edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017.

Muizelaar, Klaske, and Derek L. Phillips. “Picturing Men and Women in the Dutch Golden Age :

Paintings and People in Historical Perspective”. New Haven: Yale University Press,

2003.

Pops, Martin. Vermeer : Consciousness and the Chamber of Being. Ann Arbor, Mich: UMI

Research Press, 1984.

48

Schama, Simon. “Wives and Wantons: Versions of Womanhood in 17th Century Dutch Art.”

Oxford Art Journal 3, no. 1 (1980): 5–13. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxartj/3.1.5.

Schneider, Norbert, and Johannes Vermeer. Vermeer, 1632-1675 : Veiled Emotions. Kln:

Taschen, 2000.

Sutton, Peter C., Lisa Vergara, and Ann Jensen Adams. Love Letters : Dutch Genre Paintings in

the Age of Vermeer, London: Bruce Museum, 2003.

Waiboer, Adriaan E., Arthur K. Wheelock, Blaise Ducos, Piet Bakker, Quentin Buvelot, E.

Melanie Gifford, Lisha Deming Glinsman, Marjorie E. Wieseman, Eric Jan Sluijter, and

Eddy Schavemaker. Vermeer and the Masters of Genre Painting : Inspiration and

Rivalry. Dublin: National Gallery of Ireland, 2017.

Wieseman, Marjorie E., Johannes Vermeer, H. Perry Chapman, and Wayne E. Franits.

Vermeer’s

Women : Secrets and Silence. Cambridge: Fitzwilliam Museum, 2011.

Wolfthal, Diane. “Foregrounding the Background: Images of Dutch and Flemish Household

Servants.” In Women and Gender in the Early Modern Low Countries, edited by Sarah

Joan Moran and Amanda Pipkin, 217:229–65. Brill, 2019.

http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1163/j.ctvrxk3hp.13.