Cultural Surveys Hawai‘i Job Code: HONOULIULI 172 Traditional and Historical Background

CIA

for the West Oahu Solar Project, Honouliuli, ‘Ewa, O‘ahu

TMK: [1] 9-2-002:007

85

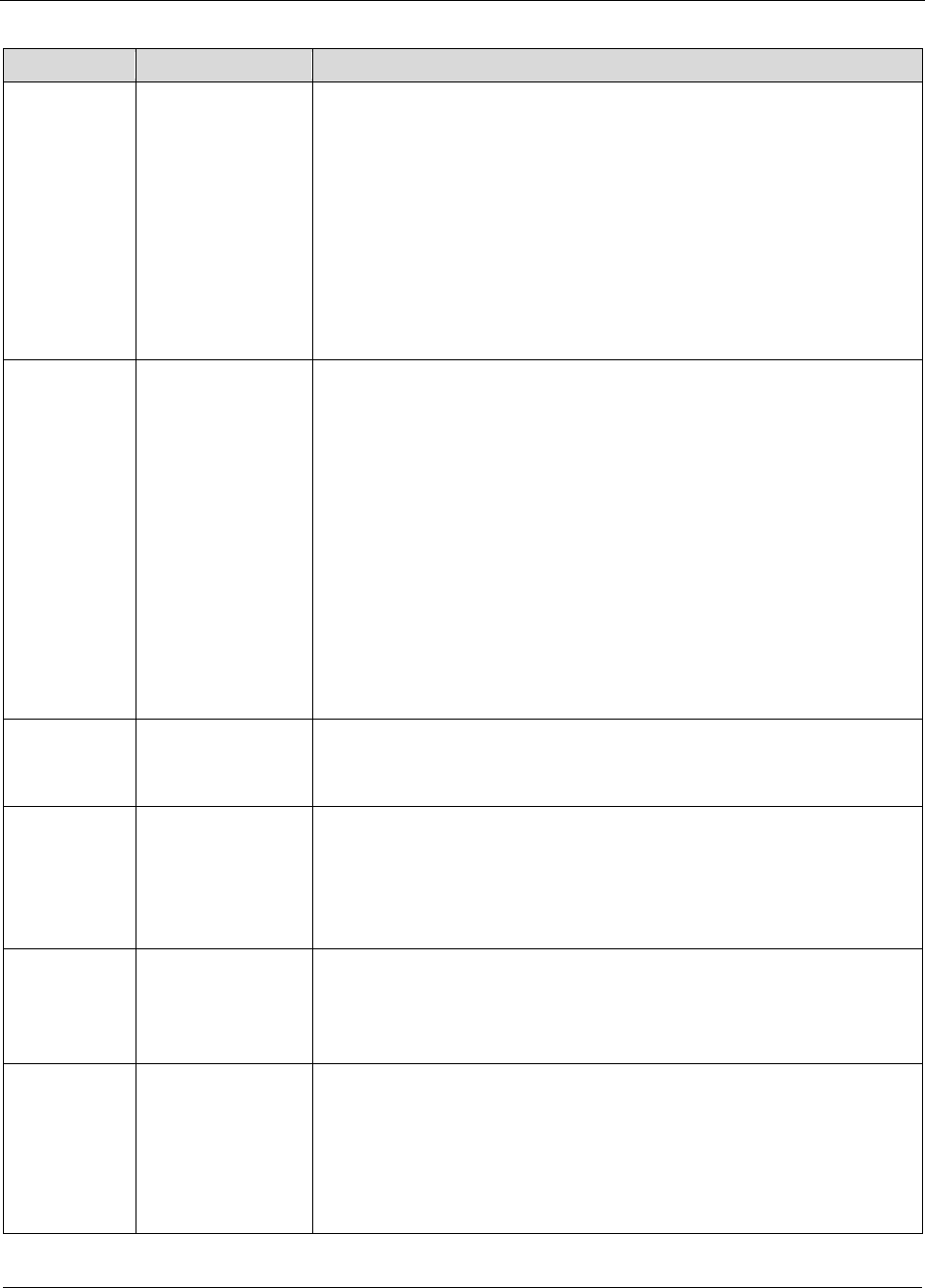

Figure 26. 1977 USGS Orthophotoquad aerial photograph, Ewa and Schofield Barracks

quadrangles showing the project area

Cultural Surveys Hawai‘i Job Code: HONOULIULI 172 Traditional and Historical Background

CIA

for the West Oahu Solar Project, Honouliuli, ‘Ewa, O‘ahu

TMK: [1] 9-2-002:007

86

Figure 27. 1993 NOAA aerial photograph (UH MAGIS) showing the project area

Cultural Surveys Hawai‘i Job Code: HONOULIULI 172 Previous Archaeological Research

CIA

for the West Oahu Solar Project, Honouliuli, ‘Ewa, O‘ahu

TMK: [1] 9-2-002:007

87

Section 5 Previous Archaeological Research

Several archaeological studies have been conducted in the vicinity of the project area. This

section discusses previous archaeological studies in the area (Figure 28 and Table 1) and identifies

the types and locations of previously identified historic properties (Figure 29 and Table 2). There

are no sites documented by McAllister (1933) in his early archaeological reconnaissance study of

O‘ahu in the vicinity of the project area.

5.1 Archaeological Investigations in the Vicinity of the Project Area

5.1.1 Bordner 1977

In 1977, the Archaeological Research Center Hawaii, Inc. (Bordner 1977) conducted an

archaeological reconnaissance survey of a then proposed Kalo‘i Gulch landfill location, 500 m

west of the present project area. The study concluded the lower section of the gulch had been

extensively modified through quarrying operations and cattle ranching. Foundations of both

crushing and loading facilities were noted. In the upper reaches of the property, three walls of

possible pre-Contact origin were documented between 1,250 and 1,300 ft elevation and were

designated as SIHP #s 50-80-12-2600, -2601 and -2602. These three historic properties were in

the extreme, upslope end of the large property more than 1.5 km from the present project area.

SIHP # -2600 was a low (only 0.61 m or 2.0 ft high) wall of poorly stacked pāhoehoe (smooth,

unbroken type of lava), approximately 7.62 m (25.00 ft) long set on top of a small knoll jutting out

from the slope. SIHP # -2600 is described as a wall built on the stream terrace cut following the

course of the stream, and constructed of stacked pāhoehoe with a total length of 67.70 m (222.1 ft),

an average height of 0.91 m (3.0 ft) and incorporating in situ boulders into the wall. The wall

appeared to have been constructed to protect a stream terrace from erosion. It also retained a terrace

measuring approximately 12.0 m (39.4 ft) by 31.0 m (101.7 ft). SIHP # 50-80-12-2602 was a free-

standing 18.2-m (59.7-ft) wall of stacked pāhoehoe that had the appearance of being a boundary

wall. The historic properties were regarded as of “a marginal status” and no further archaeological

work was recommended for the area covered in the reconnaissance survey.

5.1.2

Sinoto 1988

In 1988, the Bishop Museum Applied Research Group conducted a surface survey for a then

proposed Makakilo Golf Course just southwest of the current project area (Sinoto 1988). The study

concluded the majority of the project area had been damaged by severe erosion. No surface remains

were documented within the project area and subsurface testing was deemed unnecessary. Just

west (outside) of the golf course property, one deteriorated wall segment was documented on the

northeast slope of Pu‘u Makakilo. The wall, designated SIHP # 50-80-12-1975, may have served

as an “historic erosional control feature” (Sinoto 1988:1). Due to the deteriorated condition of the

wall remnant, no further work was recommended.

5.1.3 Spear 1996

Scientific Consultant Services, Inc. conducted an archaeological reconnaissance survey of a

large area extending from south of the H-1 freeway to the north side of Renton Road (Spear 1996).

No historic properties were identified.

Cultural Surveys Hawai‘i Job Code: HONOULIULI 172 Previous Archaeological Research

CIA

for the West Oahu Solar Project, Honouliuli, ‘Ewa, O‘ahu

TMK: [1] 9-2-002:007

88

Figure 28. Portion of the 1998 Ewa and Schofield Barracks USGS topographic quadrangles

showing the locations of previous archaeological studies in the vicinity (within

approximately 1.5 km) of the project area

Cultural Surveys Hawai‘i Job Code: HONOULIULI 172 Previous Archaeological Research

CIA

for the West Oahu Solar Project, Honouliuli, ‘Ewa, O‘ahu

TMK: [1] 9-2-002:007

89

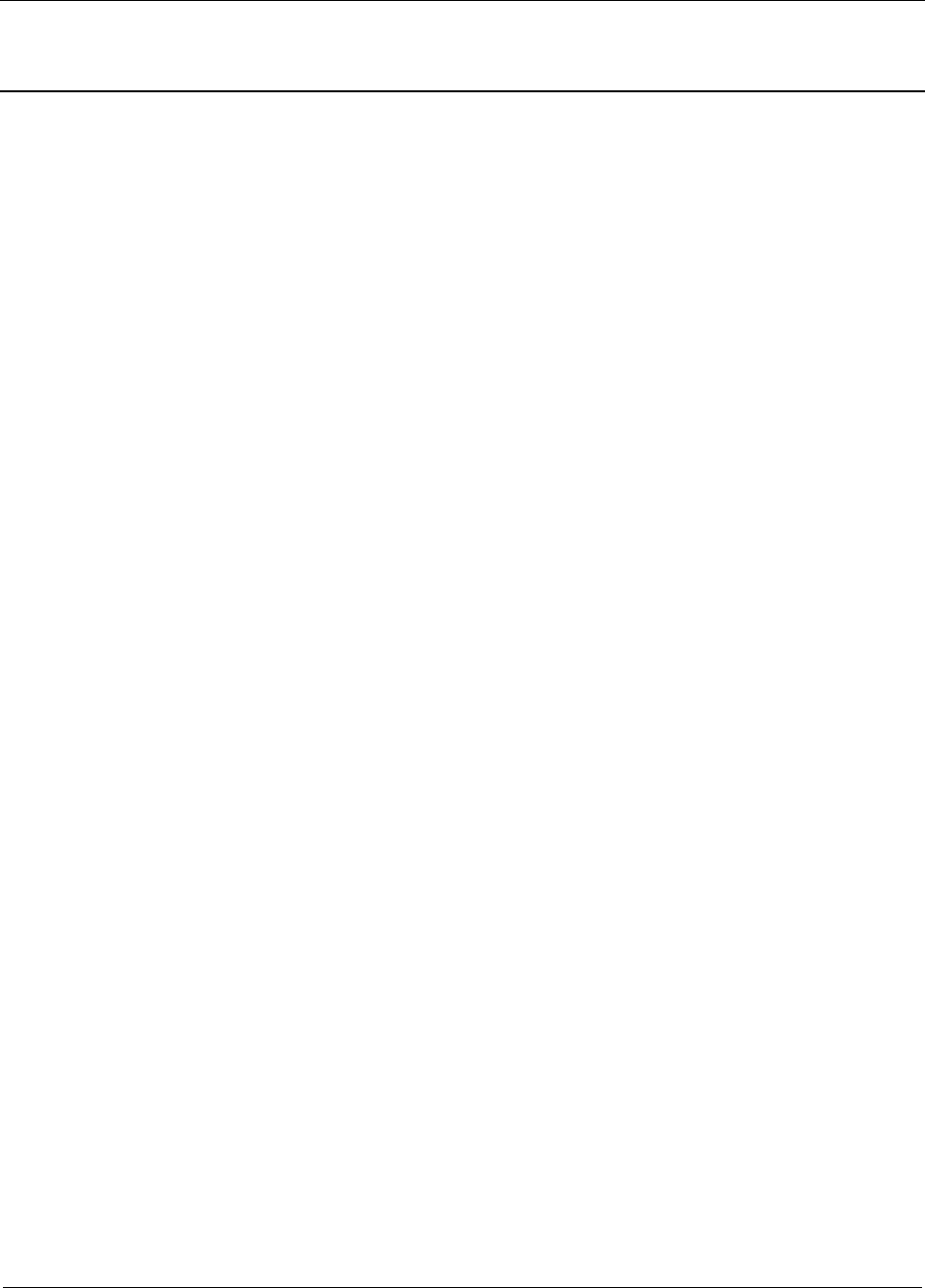

Table 1. Previous archaeological studies within the vicinity (within approximately 1.5 km) of the

project area

Author

Type of

Investigation

Location

Report Description and Results

Bordner 1977

Archaeological

reconnaissance

survey

Proposed Kalo‘i

Gulch landfill

location

Three walls designated as SIHP #s 50-80-

12-2600, -2601 and -2602 in extreme

west, upslope end of large project area,

more than 1.5 km from present project

area (and hence are not depicted in Figure

29)

Sinoto 1988

Archaeological

reconnaissance

survey

Makakilo Golf

Course

Low stacked boulder wall, SIHP # 50-80-

09-1975

Spear 1996

Archaeological

reconnaissance

survey

East Kapolei, TMK:

[1] 9-1-016:017

No historic properties identified

Dega et al.

1998

Archaeological

inventory

survey

UH West O‘ahu,

TMK: [1] 9-2-

002:001

Two historic property complexes: historic

irrigation and plantation infrastructure

system (SIHP # 50-80-08-5593) and

Waiahole Ditch System (SIHP # 50-80-

09-2268)

Magnuson

1999

Archaeological

reconnaissance

survey

‘Ewa Plain

Identified six concrete bridges, a railroad

track, and a set of unidentified concrete

features; no SIHP #s assigned

Tulchin et al.

2001

Archaeological

inventory

survey

Proposed ‘Ewa Shaft

Renovation project,

Honouliuli Gulch,

adjacent to west-

bound lanes of H-1,

TMK: [1] 9-2-001

SIHP # 50-80-08-6370, stone wall

alignment; also documented large

pumping station and shaft building

Tulchin and

Hammatt

2004

Archaeological

inventory

survey

86-acre proposed

Pālehua Community

Association, TMKs:

[1] 9-2-003:078 por.

and 079

Four historic properties identified: a

complex of concrete and iron structures

associated with industrial rock quarry

operations (SIHP # 50-80-12-6680); three

boulder mounds believed to be related to

land clearing or ditch construction by

Oahu Sugar Co. (SIHP # 50-80-12-6681);

a small terrace believed to function as a

historic water diversion feature (SIHP #

50-80-12-6682); and a remnant portion of

Waiahole Ditch (SIHP # 50-80-09-2268)

Cultural Surveys Hawai‘i Job Code: HONOULIULI 172 Previous Archaeological Research

CIA

for the West Oahu Solar Project, Honouliuli, ‘Ewa, O‘ahu

TMK: [1] 9-2-002:007

90

Author

Type of

Investigation

Location

Report Description and Results

Tulchin and

Hammatt

2005

Archaeological

inventory

survey

71-acre proposed

Pālehua East B

project, Makakilo,

TMKs: [1] 9-2-

003:076 and 078

Three historic properties identified: pre-

Contact agricultural alignment and mound

(SIHP # 50-80-12-6666), plantation-era

stacked basalt boulder walls and a ditch

(SIHP # 50-80-12-6667), and single

alignment of upright basalt boulders and a

small, low terrace (SIHP # 50-80-12-6668)

O’Hare et al.

2006

Archaeological

inventory

survey

Ho‘opili East Kapolei

Documented six previously identified

historic properties: plantation

infrastructure (SIHP # 50-80-12-4344);

railroad berm (SIHP # 50-80-12-4345);

northern pumping station (SIHP # 50-80-

12-4346); central pumping station (SIHP #

50-80-12-4347); southern pumping station

(SIHP # 50-80-12-4348); and documented

four newly identified features of SIHP #

50-80-12-4344: a linear wall, stone-faced

berm, concrete ditch, and concrete

catchment

Rasmussen

and

Tomonari-

Tuggle 2006

Archaeological

monitoring

Waiau Fuel Pipeline

corridor

No historic properties identified

Tulchin and

Hammatt

2007

Archaeological

literature

review and

field inspection

Approx. 790-acre

parcel, TMKs: [1] 9-

2-003:002 por. and

005 por.

Documented features interpreted as related

to pre-Contact indigenous Hawaiian

habitation (SIHP #s 50-80-08-2316 and

50-80-12-2602); historic ranching and

related features (SIHP # 50-80-12-2601);

and historic quarrying and related features

(SIHP # 50-80-12-6680) and various pre-

and post-Contact features (designated with

temporary #s CSH1–CSH22)

Mooney and

Cleghorn

2008

Archaeological

reconnaissance

survey

TMK: [1] 9-2-

003:018

No historic properties identified

Groza et al.

2009

Archaeological

inventory

survey

TMKs: [1] 9-2-

001:001 por., 004,

005, 006, 007 por.; 9-

2-002:002

No historic properties identified

Cultural Surveys Hawai‘i Job Code: HONOULIULI 172 Previous Archaeological Research

CIA

for the West Oahu Solar Project, Honouliuli, ‘Ewa, O‘ahu

TMK: [1] 9-2-002:007

91

Author

Type of

Investigation

Location

Report Description and Results

Hunkin and

Hammatt

2009

Archaeological

inventory

survey

TMKs: [1] 9-2-

002:006; 9-2-003:079

Documented two newly identified historic

properties: irrigation ditches (SIHP #s 50-

80-12-6950 and -6951); and one

previously identified historic property,

Waiahole Ditch (SIHP # 50-80-09-2268)

Runyon et al.

2010

Archaeological

monitoring

TMKs: [1] 9-2-

002:006; 9-2-003:079

No historic properties identified

Runyon et al.

2011

Archaeological

monitoring

TMKs: [1] 9-1-

018:001, 003, 004,

005; 9-2-002:001,

006

Documented two historic properties: a

water diversion and a trash deposit (SIHP

#s 50-80-12-4664 and -7128)

Pacheco and

Rieth 2014

Archaeological

inventory

survey

East Kapolei Solar

Farm, TMK: [1] 9-2-

002:006 por.

Documented SIHP # 50-80-12-7433, an

unpaved early twentieth century

agricultural (ranching and/or sugarcane

cultivation) road, understood as created

between 1918 and 1928

Cultural Surveys Hawai‘i Job Code: HONOULIULI 172 Previous Archaeological Research

CIA

for the West Oahu Solar Project, Honouliuli, ‘Ewa, O‘ahu

TMK: [1] 9-2-002:007

92

Figure 29. Portion of the 1998 Ewa and Schofield Barracks USGS topographic quadrangles

showing the locations of previously identified historic properties in the immediate

vicinity of the project area

Cultural Surveys Hawai‘i Job Code: HONOULIULI 172 Previous Archaeological Research

CIA

for the West Oahu Solar Project, Honouliuli, ‘Ewa, O‘ahu

TMK: [1] 9-2-002:007

93

Table 2. Previously identified historic properties in the vicinity of the project area

SIHP #

Description

Report Author(s)

50-80-08-

5593

Plantation-era “flumes, aqueducts, ditches,

pumps, and other irrigation features”

Dega et al. 1998

50-80-08-

6370

Stone wall alignment, likely associated with

cattle ranching or pumping station

Tulchin et al. 2001

50-80-09-

2268

Waiahole Ditch System

Goodman and Nees 1991;

Hammatt et al. 1996; Dega et al.

1998; Tulchin and Hammatt

2005; Hunkin and Hammatt

2009; Zapor et al. 2018;

Shideler and Hammatt 2018

50-80-08-

9068

Honouliuli National Monument (Internment

Camp)

National Register

50-80-12-

1975

Low-stacked boulder wall segment

Sinoto 1988

50-80-12-

4664

Historic water diversion structure

Nakamura et al. 1993; Runyon

et al. 2011

50-80-12-

6666

Alignment and mound

Tulchin and Hammatt 2005

50-80-12-

6667

Two walls

Tulchin and Hammatt 2005

50-80-12-

6668

Alignment and terrace

Tulchin and Hammatt 2005

50-80-12-

6680

Complex of concrete and iron structures

associated with industrial rock quarry

operations

Tulchin and Hammatt 2005

50-80-12-

6681

Three boulder mounds believed to be related to

land clearing or ditch construction by the Oahu

Sugar Company

Tulchin and Hammatt 2005

50-80-12-

6682

Terrace believed to function as an historic

water diversion feature

Tulchin and Hammatt 2005

50-80-12-

6950

Portion of a plantation-era irrigation ditch

Hunkin and Hammatt 2009

50-80-12-

6951

Portion of a plantation-era irrigation ditch

Hunkin and Hammatt 2009

50-80-12-

7128

Burned trash fill layer

Runyon et al. 2011

Cultural Surveys Hawai‘i Job Code: HONOULIULI 172 Previous Archaeological Research

CIA

for the West Oahu Solar Project, Honouliuli, ‘Ewa, O‘ahu

TMK: [1] 9-2-002:007

94

SIHP #

Description

Report Author(s)

50-80-12-

7433

Unpaved early twentieth century agricultural

(ranching and/or sugarcane cultivation) road,

understood as created between 1918 and 1928

Pacheco and Rieth 2014

50-80-12-

7484

Post-Contact irrigation ditch portion

Pacheco and Rieth 2014

50-80-12-

7485

Post-Contact irrigation ditch portion

Pacheco and Rieth 2014

Historic

Bridges

No SIHP #s assigned, no further

documentation or mitigation recommended

Magnuson 1999

Military

Bunker

WWII-era bunker

Mooney and Cleghorn 2008

CSH 1

Post-Contact wall related to historic ranching

Tulchin and Hammatt 2007

CSH 2

(Mounds)

Two basalt mounds interpreted as possible trail

markers

Tulchin and Hammatt 2007

Cultural Surveys Hawai‘i Job Code: HONOULIULI 172 Previous Archaeological Research

CIA

for the West Oahu Solar Project, Honouliuli, ‘Ewa, O‘ahu

TMK: [1] 9-2-002:007

95

5.1.4 Dega et al. 1998

In 1998, Scientific Consultant Services, Inc. (SCS) conducted an archaeological inventory

survey (AIS) for the University of Hawai‘i, West O‘ahu Campus project area (Dega et al. 1998).

The project encompassed the entirety of the current project area. Several plantation-era “flumes,

aqueducts, ditches, pumps, and other irrigation features occurring within the heavily modified

landscape of the project area” were noted (Dega et al. 1998:i). The features represented an

extensive complex of sugarcane irrigation features used from the 1920s through more recent times.

The irrigation complex was designated SIHP # 50-80-08-5593. A portion of the Waiahole Ditch

System (SIHP # 50-80-09-2268) (previously recorded by Goodman and Nees 1991) was also

documented crossing through the northwest section of the subject parcel and continuing southwest

through the lower agricultural fields. No artifacts were recovered from the project area. No further

work was recommended for SIHP # 50-80-08-5593.

An overlay of the present project area on the Dega et al. (1998) plan map (Figure 30) indicates

that it lies entirely within the south/central portion of that 1998 AIS project. While the Dega et al.

(1998) plan map should probably be understood as a sketch, it does indicate certain remnants of

plantation infrastructure (designated as SIHP # 50-80-08-5593) were present in the present project

area in 1998.

5.1.5 Magnuson 1999

In 1999, an archaeological reconnaissance survey was completed by International

Archaeological Research Institute, Inc. (IARII) for a Farrington Highway Expansion project

extending along 5.3 km (3.3 miles) of Farrington Highway between Golf Course Road and Fort

Weaver Road with a roughly 61-m (200-ft) wide corridor on each side (Magnuson 1999). The

project identified six concrete bridges, one railroad track, and “a set of unidentified concrete

features” (Magnuson 1999:17). The study concluded the following:

The sites observed in the Farrington Highway Expansion project are neither

exemplary sites of their kind nor unique. Therefore these sites have been adequately

recorded during the investigations and no further work is necessary should

preservation not be possible. [Magnuson 1999:25]

5.1.6 Tulchin et al. 2001

CSH archaeologists completed an AIS in support of a proposed ‘Ewa Shaft Renovation project.

The ‘Ewa Shaft project is within Honouliuli Gulch, adjacent to the west-bound lanes of the H-1

Interstate Highway, approximately 1.7 km east of the present project area. That property included

a pumping station enclosure and the surrounding area of approximately 1 acre. One historic

property was documented, a stone wall alignment designated SIHP # 50-80-08-6370. Subsurface

testing was conducted adjacent to the wall. The wall alignment was interpreted as constructed in

association with cattle ranching or the pumping station. The study also documented a portion of

the large pumping station and shaft building on the property.

5.1.7 Tulchin and Hammatt 2004

In 2004, CSH conducted an AIS to the west of the current project area for the Pālehua

Community Association (PCA) in Makakilo (Tulchin and Hammatt 2004). Three overhang

shelters were observed and tested, however, no cultural material was identified during excavation.

Cultural Surveys Hawai‘i Job Code: HONOULIULI 172 Previous Archaeological Research

CIA

for the West Oahu Solar Project, Honouliuli, ‘Ewa, O‘ahu

TMK: [1] 9-2-002:007

96

Figure 30. Plan map of the AIS for the University of Hawai‘i, West O‘ahu Campus project area

showing historic properties (as of 1998) with an overlay of the current project area

(adapted from Dega et al. 1998:3). This overlay suggests “Pump Station 12 and Mill”

and a ditch were documented as within the present project area and another ditch and

road and “Stone stack” were adjacent to the north side of the present project area.

Cultural Surveys Hawai‘i Job Code: HONOULIULI 172 Previous Archaeological Research

CIA

for the West Oahu Solar Project, Honouliuli, ‘Ewa, O‘ahu

TMK: [1] 9-2-002:007

97

The study documented several historic properties, including a complex of concrete and iron

structures associated with industrial rock quarry operations (SIHP # 50-80-12-6680); three boulder

mounds believed to be related to land clearing or ditch construction by the Oahu Sugar Company

(SIHP # 50-80-12-6681); a small terrace believed to function as an historic water diversion feature

(SIHP # 50-80-12-6682); and a remnant portion of the Waiahole Ditch (SIHP # 50-80-09-2268).

5.1.8 Tulchin and Hammatt 2005

In 2005, CSH conducted an AIS west of the current project area for the proposed Pālehua East B

project in Makakilo (Tulchin and Hammatt 2005). The study identified three historic properties,

including an alignment and a mound (SIHP #s 50-80-12-6666A and B), two walls (SIHP #s 50-

80-12-6667A and B), and an alignment and terrace (SIHP #s 50-80-12-6668A and B). SIHP # 50-

80-12-6667 is thought to contain remnants of plantation infrastructure. The historic properties were

documented in an unnamed gully south of Kalo‘i Gulch.

5.1.9 O’Hare et al. 2006

In 2006, CSH conducted an AIS of approximately 1,600 acres for the East Kapolei project

(subsequently known as the Ho‘opili project) (O’Hare et al. 2006) to the southeast of the present

project area. The Ho‘opili project was bounded on the east by Fort Weaver Road, makai by Mango

Tree Road, and mauka by the H-1 Freeway.

Several historic properties documented by the O’Hare et al. (2006) study were previously

identified during an archaeological survey in 1990 (Hammatt and Shideler 1990). These previously

identified historic properties included SIHP # 50-80-12-4344, plantation infrastructure; SIHP #

50-80-12-4345, railroad berm; SIHP # 50-80-12-4346, northern pumping station; SIHP # 50-80-

12-4347, central pumping station; and SIHP # 50-80-12-4348, southern pumping station. Four

additional archaeological features were documented by the O’Hare et al. (2006) study. These

additional features, grouped under SIHP # 50-80-14-4344, include Feature D, a linear wall along

the east bank of Honouliuli Stream; Feature E, a linear wall along the west bank of Honouliuli

Stream; Feature F, a stone-faced berm constructed perpendicular to the orientation of the stream;

and Feature G, a concrete ditch and concrete masonry catchment basement on the west bank of

Honouliuli Gulch. None of the historic properties identified in the O’Hare et al. study (2006) were

near the present project area.

5.1.10 Rasmussen and Tomonari-Tuggle 2006

In 2006, IARII conducted archaeological monitoring along the Waiau Fuel Pipeline corridor,

extending from the Hawaiian Electric Company’s Barbers Point Tank Farm to the Waiau

Generating Station (Rasmussen and Tomonari-Tuggle 2006). The Waiau Fuel Pipeline corridor

follows Farrington Highway to Kunia Road, angles makai near Kunia Road, then continues east

along the OR&L right-of-way near the Pearl Harbor coast. It appears no archaeological monitoring

was conducted west of Waipi‘o Peninsula, as the corridor to the west had been determined to not

be archaeologically sensitive. No historic properties were identified during archaeological

monitoring.

5.1.11 Tulchin and Hammatt 2007

In 2007, an archaeological literature review and field inspection (Tulchin and Hammatt 2007)

was done of an approximately 790-acre parcel at Pālehua, Makakilo. The inspection covered

Cultural Surveys Hawai‘i Job Code: HONOULIULI 172 Previous Archaeological Research

CIA

for the West Oahu Solar Project, Honouliuli, ‘Ewa, O‘ahu

TMK: [1] 9-2-002:007

98

portions of Makaīwa Gulch, Awanui Gulch, and Kalo‘i Gulch. Overall, 26 archaeological historic

properties were identified during the field inspection. Four of these historic properties were

identified during previous archaeological studies. SIHP # 50-80-08-2316 consists of a ku‘ula stone

documented by the Bishop Museum (Kelly 1959). SIHP # 50-80-12-2601, a pre-Contact wall

utilized as a water control feature, and SIHP # 50-80-12-2602, a pre-Contact wall possibly utilized

for agriculture, were originally documented by Bordner in 1977 (Bordner 1977). SIHP # 50-80-

12-6680, a complex of concrete and iron structures associated with industrial rock quarry

operations was identified by CSH in 2004 (Tulchin and Hammatt 2004).

Newly identified historic features (designated with temporary CSH site #s) included CSH 1,

wall; CSH 2, mounds; CSH 3, large enclosure; CSH 4, platform; CSH 5, mounds; CSH 6, adze;

CSH 7, platform; CSH 8, terraces; CSH 9, enclosure and two small caves; CSH 10, enclosure;

CSH 11, mound; CSH 12, platform; CSH 13, enclosure; CSH 14 terrace; CSH 15, wall remnant,

hearth, and military “foxhole”; CSH 16, terrace and hau thicket; CSH 17, level soil along ridge;

CSH 18, enclosure; CSH 19, trail; CSH 20 water tunnel; CSH 21, large boulder with petroglyphs;

and CSH 22, enclosure with stone uprights. These potential historic properties were not assigned

SIHP #s.

Other than the previously reported SIHP # -6680 complex of structures associated with

industrial rock quarry operations, none of the identified historic properties were in the vicinity of

the present project area.

5.1.12 Mooney and Cleghorn 2008

In 2008, Pacific Legacy, Inc. conducted an AIS (recorded as an archaeological assessment due

to lack of finds) for the proposed Makakilo Quarry expansion (Mooney and Cleghorn 2008). No

historic properties were identified; however, the remnants of a modern, abandoned golf course

were noted.

5.1.13 Groza et al. 2009

In 2009, CSH conducted an AIS (recorded as an archaeological assessment) for the Ho‘opili

project 440-Ft Elevation Reservoir and Water Line project (Groza et al. 2009). No historic

properties were identified.

5.1.14 Hunkin and Hammatt 2009

In 2009, CSH completed an archaeological inventory survey for an approximately 62-acre

Makakilo Drive extension project (Hunkin and Hammatt 2009). The project documented two

newly identified historic properties (SIHP #s 50-80-12-6950 and -6951). Both historic properties

are portions of plantation irrigation ditches. The ditches functioned to transport water for irrigation

of the sugarcane fields.

In addition to the newly identified historic properties, a portion of the previously identified

SIHP # 50-80-09-2268 alignment was documented. A meeting was held on site within the project

area with CSH staff, SHPD staff, and Mr. Shad Kāne on 10 February 2009 to discuss the alignment

within the project area. Mr. Kāne led the group along the graded alignment of SIHP # 50-80-09-

2268, indicating the ditch had been constructed over the alignment of an ancient Hawaiian trail.

SHPD staff observed the plantation irrigation ditch and associated infrastructure and concurred the

alignment was a portion of the Waiahole Ditch System. SHPD staff also concluded the ditch was

Cultural Surveys Hawai‘i Job Code: HONOULIULI 172 Previous Archaeological Research

CIA

for the West Oahu Solar Project, Honouliuli, ‘Ewa, O‘ahu

TMK: [1] 9-2-002:007

99

most likely constructed over the alignment of a pre-Contact Hawaiian trail. SHPD staff expressed

a concern that documentation make it clear the pre-Contact Hawaiian trail function was the

dominant function of this designated site in the vicinity (which was then developed as the Waiahole

Ditch in the early twentieth century).

Two new features (SIHP # 50-80-09-2268 Features B and C) associated with the main ditch

were also documented. These features are drainage-related, with the function of preventing storm

water and sediment from entering the main Waiahole Ditch.

5.1.15 Runyon et al. 2010

In 2010, CSH conducted archaeological monitoring for Phase 1B of the North-South Road

project (Runyon et al. 2010). No historic properties were identified.

5.1.16 Runyon et al. 2011

In 2011, CSH completed archaeological monitoring for phase 1C of the North-South Road

project (Runyon et al. 2011). Two historic properties were observed. A previously identified

historic water diversion structure (SIHP # 50-80-12-4664), originally documented by Nakamura

et al. (1993), was observed on the southwest edge of Ramp C. A newly identified burnt trash fill

layer (SIHP # 50-80-12-7128) was documented directly under Pālehua Road on the west edge of

Ramp A.

5.1.17 Pacheco and Rieth 2014

In 2014, IARII conducted an AIS (Pacheco and Rieth 2014) for an East Kapolei Solar Farm

project (on approximately 19 acres of TMK: [1] 9-2-002:006).The study documented one historic

property: SIHP # 50-80-12-7433, an unpaved early twentieth century road related to ranching

and/or sugarcane cultivation in the area, understood as created between 1918 and 1928.

5.1.18 Zapor et al. 2018

CSH conducted a supplemental AIS for the Makakilo Drive Extension project. The survey

identified two historic properties: portions of the Waiahole Ditch (SIHP # 50-80-09-2268) and

irrigation ditches (SIHP # 50-80-12-6951). The project documented an additional feature of the

Waiahole Ditch, an earthen mound and stacked stone wall, interpreted as likely remnants of a

reservoir. SIHP # 50-80-12-6951 was observed as an irrigation ditch and associated retaining wall,

pipe, valve, and sluice gate remnants.

Cultural Surveys Hawai‘i Job Code: HONOULIULI 172 Community Consultation

CIA

for the West Oahu Solar Project, Honouliuli, ‘Ewa, O‘ahu

TMK: [1] 9-2-002:007

100

Section 6 Community Consultation

6.1 Introduction

Throughout the course of this assessment, an effort was made to contact and consult with Native

Hawaiian Organizations (NHO), agencies, and community members including descendants of the

area, in order to identify individuals with cultural expertise and/or knowledge of the ahupua‘a of

Honouliuli. CSH initiated its outreach effort in May 2019 through letters, email, telephone calls,

and in-person contact.

6.2 Community Contact Letter

Letters (Figure 31 and Figure 32) along with a map and an aerial photograph of the project were

mailed with the following text:

On behalf of AES Distributed Energy, Inc. (AES), Cultural Surveys Hawai‘i Inc.

(CSH) is conducting a cultural impact assessment (CIA) for the AES West O‘ahu

Solar Plus Storage Project, Honouliuli Ahupua‘a, ‘Ewa District, O‘ahu Island. AES

is proposing a solar photovoltaic (PV) and battery energy storage system (BESS)

project to be located approximately 3 miles northeast of Kapolei in West Oʻahu.

The project area includes approximately 80 acres and is within a portion of tax map

key (TMK) 9-2-002:007, which is owned by the University of Hawai‘i (UH) in an

area commonly referred to as the UH West O‘ahu Mauka property. The project area

is depicted on a portion of the 2013 Ewa and Schofield Barracks U.S. Geological

Survey (USGS) 7.5-minute topographic quadrangles, and 2018 Google Earth aerial

photograph.

The proposed project will involve construction and operation of an approximately

12.5-megawatt (MW) ground-mounted solar PV system, coupled with a 50 MW-

hour BESS and related interconnection and ancillary facilities. The solar PV panels

will be arranged in a series of evenly-spaced rows across the project area. The BESS

will consist of containerized lithium-ion battery units and inverters distributed

across the project area. This equipment will connect with a project substation via

underground electrical conduit. The substation will be constructed adjacent to an

existing Hawaiian Electric Company (HECO) 46kV transmission line that traverses

the project area and will facilitate interconnection of the project to the HECO grid;

an overhead electrical connection between the substation and existing transmission

line may be required for interconnection. The project will be accessed via the

existing gated entry off Kualakai Parkway and will utilize a network of existing and

new onsite access roads. Some site grading will be needed to accommodate the

project facilities and to comply with stormwater and civil engineering requirements

and some of the existing access roads may need to be improved to support access

to the project site. The project area will be secured for use by AES through a long-

term lease (or similar agreement) with UH. The Project will be owned and operated

by AES, and the power generated by the Project will be sold to HECO under a new

25-year power purchase agreement (PPA). It is anticipated that construction will

Cultural Surveys Hawai‘i Job Code: HONOULIULI 172 Community Consultation

CIA

for the West Oahu Solar Project, Honouliuli, ‘Ewa, O‘ahu

TMK: [1] 9-2-002:007

101

Figure 31. Community consultation letter page one

Cultural Surveys Hawai‘i Job Code: HONOULIULI 172 Community Consultation

CIA

for the West Oahu Solar Project, Honouliuli, ‘Ewa, O‘ahu

TMK: [1] 9-2-002:007

102

Figure 32. Community consultation letter page two

Cultural Surveys Hawai‘i Job Code: HONOULIULI 172 Community Consultation

CIA

for the West Oahu Solar Project, Honouliuli, ‘Ewa, O‘ahu

TMK: [1] 9-2-002:007

103

require approximately 12-15 months, with commercial operations commencing in

2021 or 2022.

The purpose of this CIA is to gather information about the project area and the

surrounding area through research and interviews with individuals that are

knowledgeable about this area in order to assess potential impacts to cultural

resources, cultural practices, and beliefs as a result of the proposed project. We are

seeking your kōkua and guidance regarding the following aspects of our study:

• General history as well as present and past land use of the project area

• Knowledge of cultural sites which may be impacted by future development

of the project area—for example, historic and archaeological sites, as well

as burials

• Knowledge of traditional gathering practices in the project area, both past

and ongoing

• Cultural associations of the project area, such as mo‘olelo and traditional

uses

• Referrals of kūpuna or elders and kama‘āina who might be willing to share

their cultural knowledge of the project area and the surrounding ahupua‘a

lands

• Any other cultural concerns the community might have related to

Hawaiian cultural practices within or in the vicinity of the project area

In December 2019, CSH was notified of a slight modification to the project area to include

additional areas along the perimeter of the project area, as well as maintenance of the existing

roadways approaching the project area from the southeast. Revised letters (Figure 33 and Figure

34) along with a map and aerial photograph of the project area were mailed with the following

revised text.

In May and June 2019, Cultural Surveys Hawai‘i (CSH), on behalf of AES

Distributed Energy, Inc., reached out to the Honouliuli community regarding a

cultural impact assessment (CIA) for the West O‘ahu Solar Project, Honouliuli

Ahupua‘a, ‘Ewa District, O‘ahu Island TMK: [1] 9-002:007. As the project area

has changed slightly, we are seeking additional input as part of the CIA consultation

process.

As described in the previous consultation letter, the proposed West O‘ahu Solar

project will involve construction and operation of an approximately 12.5-megawatt

(MW) ground-mounted solar PV system, coupled with a 50 MW-hour BESS and

related interconnection and ancillary facilities. The solar PV panels will be arranged

in a series of evenly-spaced rows across the project area. The BESS will consist of

containerized lithium-ion battery units and inverters distributed across the project

area. This equipment will connect with a project substation via underground

electrical conduit. The substation will be constructed adjacent to an existing

Hawaiian Electric Company (HECO) 46kV transmission line that traverses the

project area and will facilitate interconnection of the project to the HECO grid; an

Cultural Surveys Hawai‘i Job Code: HONOULIULI 172 Community Consultation

CIA

for the West Oahu Solar Project, Honouliuli, ‘Ewa, O‘ahu

TMK: [1] 9-2-002:007

104

Figure 33. Revised community consultation letter page one

Cultural Surveys Hawai‘i Job Code: HONOULIULI 172 Community Consultation

CIA

for the West Oahu Solar Project, Honouliuli, ‘Ewa, O‘ahu

TMK: [1] 9-2-002:007

105

Figure 34. Revised community consultation letter page two

Cultural Surveys Hawai‘i Job Code: HONOULIULI 172 Community Consultation

CIA

for the West Oahu Solar Project, Honouliuli, ‘Ewa, O‘ahu

TMK: [1] 9-2-002:007

106

overhead electrical connection between the substation and existing transmission

line may be required for interconnection. The project will be accessed via the

existing gated entry off Kualaka‘i Parkway and will utilize a network of existing

and new onsite access roads. Some site grading will be needed to accommodate the

project facilities and to comply with stormwater and civil engineering requirements

and some of the existing access roads may need to be improved to support access

to the project site. The project area will be secured for use by AES through a long-

term lease (or similar agreement) with UH. The Project will be owned and operated

by AES, and the power generated by the Project will be sold to HECO under a new

25-year power purchase agreement (PPA). It is anticipated that construction will

require approximately 12-15 months, with commercial operations commencing in

2021 or 2022.

Recently, CSH was notified of a slight modification to the project area to include

additional areas along the perimeter of the project area, as well as maintenance of

the existing roadways approaching the project area from the southeast. Both the

original project area and the revised project area are depicted in the attached figures

(please refer to Figure 1 and Figure 2 noting “Original Project Area” and Figure 3

and Figure 4 noting “Revised Project Area”).

The purpose of this CIA is to gather information about the project area and the

surrounding area through research and interviews with individuals that are

knowledgeable about this area in order to assess potential impacts to cultural

resources, cultural practices, and beliefs as a result of the proposed project.

Specifically, the input sought through the CIA process includes the following

aspects:

• General history as well as present and past land use of the project area

• Knowledge of cultural sites which may be impacted by future development

of the project area—for example, historic and archaeological sites, as well

as burials

• Knowledge of traditional gathering practices in the project area, both past

and ongoing

• Cultural associations of the project area, such as mo‘olelo and traditional

uses

• Referrals of kūpuna or elders and kama‘āina who might be willing to share

their cultural knowledge of the project area and the surrounding ahupua‘a

lands

• Any other cultural concerns the community might have related to

Hawaiian cultural practices within or in the vicinity of the project area

In most cases, two or three attempts were made to contact individuals, organizations, and

agencies. Community outreach letters were sent to a total of 70 individuals or groups, 12

responded, one provided written testimony, and three of these kama‘āina and/or kupuna met with

Cultural Surveys Hawai‘i Job Code: HONOULIULI 172 Community Consultation

CIA

for the West Oahu Solar Project, Honouliuli, ‘Ewa, O‘ahu

TMK: [1] 9-2-002:007

107

CSH for more in-depth interviews. The results of the community consultation process are

presented in Table 3.

6.3 Community Contact Table

Below in Table 3 are names, affiliations, dates of contact, and comments from NHOs,

individuals, organizations, and agencies contacted for this project. Results are presented below in

alphabetical order.

Table 3. Community contact table

Name

Affiliation

Comment

Alaka‘i,

Robert

Cultural

practitioner

Letter and Figures sent via USPS 14 May 2019

Letter and Figures sent via email 15 May 2019

Letter and Figures sent via email 28 June 2019

Revised Letter and Figures sent via email 3 January 2020

Barbieto,

Leda

Raised in Ewa

Plantation

(Banana / Varona

Camp)

Letter and Figures sent via USPS 14 May 2019

Letter and Figures sent via USPS 27 June 2019

Revised Letter and Figures sent via USPS 3 January 2020

Barbieto,

Pio

Raised in Ewa

Plantation

(Banana / Varona

Camp)

Letter and Figures sent via USPS 14 May 2019

Letter and Figures sent via USPS 27 June 2019

Revised Letter and Figures sent via USPS 3 January 2020

Basham,

Leilani

Associate

Professor of

Hawaiian-Pacific

Studies,

University of

Hawai‘i

(UHWO)

Letter and Figures sent via email 15 May 2019

Letter and Figures sent via email 28 June 2019

Revised Letter and Figures sent via email 3 January 2020

Berg, Tom

Former

Councilman,

District 1

Mr. Berg contacted CSH via email 19 August 2019. His

comments are provided below verbatim: Please accept my

comments for the Cultural Impact Assessment – AES West

Oahu Solar and Storage Project-

Please see attached [Tom Berg’s letter is provided in full in

Appendix A].

In brief- I captured hundreds of sightings of pueo on camera-

many are on youtubes- these pueo are along the Hunehune and

Kaloi and Honouliuli Gulch Corridor which is served by the

hill/slope where you favor the development.

But with all this evidence of pueo right there on youtubes- to

this day, UHWO / Attorney General / UH BOR / DLNR /

USFWS / and OEQC claim in concert the videos are “fake” -

Cultural Surveys Hawai‘i Job Code: HONOULIULI 172 Community Consultation

CIA

for the West Oahu Solar Project, Honouliuli, ‘Ewa, O‘ahu

TMK: [1] 9-2-002:007

108

Name

Affiliation

Comment

Berg, Tom

(cont.)

Former

Councilman,

District 1

How did they do that--come to the conclusion my videos of

pueo are fake?

The answer is- the proof- smoking gun if you will- whereby the

Hawaii State Attorney General Claire Connors wrote a letter

to State Representatives Bob McDermott and Rida Cabanilla

on February 26, 2019 that reads- paraphrasing [following

bold text is in the original]:

“No pueo use the property at UHWO- for no habitat is

present on the property for the pueo to use-

and thus, no pueo

and their habitat existed or is on the property- per scientific

research, surveys, and the Environmental Impact Statement

done for the property.”

Result? Entire pueo habitat destroyed. Pueo wrongfully

extirpated from the property due to faulty protocol to

inventory for these species from the onset.

But alas- everyone can see with their own eyes two pueo

engaged in courtship behavior at UHWO in these opening

scenes [following bold text is in the original] -see video link

pasted below- and it’s a travesty our Attorney General would

lie like this (and Chair DLNR Suzanne Case) and refute these

scenes as rather being “fake and manufactured” and actually

promote a faulty and deceptive representation of the property.

The research/surveys that the Attorney General referenced in

her letter covered up the fact the survey and research failed to

include /physically go to the property for five months during

the period/season when the pueo use and occupy UHWO:

[link to Chant for Pueo @ UHWO by Michael Kumukauoha

Lee]

The pueo (and Hoary Bat) have been wrongfully extirpated

from UHWO Makai Segment- and have henceforth, as can be

proven, “transferred” their ecosystem/reliance from UHWO

Makai Segment to the hill/UHWO Mauka Segment that you

want to develop and place solar panels on.

Remember now- DBEDT is bent on allowing what I have

deduced to be possible illegal illumination of lighting on the

Monsanto farm fields right next to your proposed solar project.

The glare from these lights will most likely blind many avian

species when reflected from your solar panels- at least

contribute to their peril.

Question is- are you going to adequately look for the bats and

pueo or not at the solar project site before you blitz the area-

what will be your protocol be to look for the endangered

species on the property?

Cultural Surveys Hawai‘i Job Code: HONOULIULI 172 Community Consultation

CIA

for the West Oahu Solar Project, Honouliuli, ‘Ewa, O‘ahu

TMK: [1] 9-2-002:007

109

Name

Affiliation

Comment

Berg, Tom

(cont.)

Former

Councilman,

District 1

CSH replied via email 6 September 2019: Mahalo for your

response. We appreciate your input and acknowledge your

concerns regarding the pueo and ‘ōpe‘ape‘a habitat within the

project area and the importance of these species in Hawaiian

culture. Your comments and concerns will be incorporated and

addressed in the cultural impact assessment. Other due

diligence studies that are being conducted for the project

include an assessment of biological resources; your input

regarding survey protocols for the two species will be shared

with the biologists. The results of both the cultural and

biological due diligence studies and impact analyses for the

project will be included in an environmental assessment (EA)

which will be published for public review.

Mr. Berg replied via email 6 September 2019: With the

assistance of Senator Mike Gabbard, we are now astute as to

what the illumination of the night sky is all about near the

proposed solar project @ Monsanto.

Thank you for responding and please do include the lighting

information- provided with and by Senator Gabbard’s

Office/and DBEDT---Lights are used for soy bean growth and

lighting are able to violate State Illumination Law as farmers

were given waivers to blind migratory species.

Please do inquire with Project Pueo Biologist Team- Dr.

Melissa Price- and Dr. Javier Cotin and USFWS Jenny

Hoskins- and DOFAW Biologist Afsheen Siddiqi- about pueo

protocol.

Mind you- this Pueo team approved of the FEIS (2005) for

500-acres of property known as UHWO - saying no pueo are

there--

I should say rather - these pueo experts had no objections to

the FEIS protocol used at UHWO---------whereby in the

biological survey for pueo at UHWO- get this---- the observer

only looked for a few hours TOTAL over a period of two days

within a week during the month of April when the pueo are not

there......and to cover 500-acres------and the DLNR stated in

writing in the FEIS for UHWO--- “That was a thorough

inventory process to search for pueo- satisfactory.”

DLNR went on to state---

“That’s good enough of a look for us- only 3-4 hours of

observation need take place to determine on 500-acres if pueo

are on the property or not.” ---And – in the FEIS for UHWO-

they looked mid-morning hour- not before sunrise or at sunset

when pueo are active----but mid morning when that bird ain’t

to be seen.

Cultural Surveys Hawai‘i Job Code: HONOULIULI 172 Community Consultation

CIA

for the West Oahu Solar Project, Honouliuli, ‘Ewa, O‘ahu

TMK: [1] 9-2-002:007

110

Name

Affiliation

Comment

Berg, Tom

(cont.)

Former

Councilman,

District 1

DLNR has proven they are corrupt and very dishonest indeed--

--

These Project Pueo experts know that pueo do not have a

defined breeding season- and are plot hoppers- and will deploy

a foraging ecology- a breeding ecology- at different times of

the seasons- and hence, these experts have stated that it is

prudent to have the biological survey for pueo be conducted

year round.

These same pueo experts will also state the observation needs

to take place at sunset and sunrise- if to be a proper protocol

deployed.

Can you answer if that will be done on this solar property?

Year round observation?

I have CC’d the Project Pueo experts in this email to have

them confirm what a proper protocol of a duration of time

should be deployed in which to observe a property / conduct

the inventory/survey.

I hope a three to four hour look on one day, then another

couple of hours of a look on another day is not the protocol

you will be using- and to do it while sitting in a car eating a

burger and sipping on a milk shake. . . . like the protocol they

used for UHWO.

CSH sent summary of written testimony to Mr. Berg for

approval via email on 2 October 2019

Mr. Berg replied via email 3 October 2019:

Wow- it’s beautiful- your work- my verbiage was a bit sloppy-

So- I found two places where I made a mistake-

and two areas I

lacked the supporting documentation- four points total---

1. On page 2- I stated it was the UHWO Mauka Segement-

oops- I meant the Makai Segment-

And - the date the FEIS was executed- accepted and signed by

the Governor was in February of 2007, and not executed in

2005 or 2006 where referenced. Maybe the inventory exercise

took place in 2005/2006- but it wasn’t codified until 2007-

2. Date was 2007- date it was accepted.

3. I should have included the video links to justify the claim of

Willful Indifference, Institutional Prejudice, Administrative

Bias- - I am making a serious claim here- and this two-part

video is my evidence to defend and substantiate my claim- it

would be appreciated if you would attach it somehow--- :

[link to Mike Lee: The Willful Indifference /Pueo Habitat @

UHWO p.1; Mike Lee Willful Indifference @ UHWO p. 2]

This is relevant for the purpose that pueo extirpated from

UHWO Hunehune and Kalio Gulches - headed mauka for

Cultural Surveys Hawai‘i Job Code: HONOULIULI 172 Community Consultation

CIA

for the West Oahu Solar Project, Honouliuli, ‘Ewa, O‘ahu

TMK: [1] 9-2-002:007

111

Name

Affiliation

Comment

Berg, Tom

(cont.)

Former

Councilman,

District 1

refuge- they can’t go east- can’t go west- can’t go south- so

they went north up the gulches as this was their only option-

and they need the slopes where these solar farm(s) are to be

placed to have habitat for the pueo to forage- of course, only if

the pueo has been determined as present via an adequate

survey performed for the property ----

4. And finally- the lights that blind the bats and owls- and

others- these grow lights- may have been the cause of this barn

owl to lose its eye- this owl was found dead one -half mile from

the solar site- and this video is relevant as evidence - for I

captured it flying back and forth under the grow lights-

I have a

youtube on it- not included below- and just a few weeks later-

it

died with this eye injury---DLNR refused to accept the carcass

for a necropsy.

I would appreciate if this evidence in the video- were too

added- to support and substantiate my claim - for since no

necropsy was performed, my claim in the video may be wrong-

and the owl did not suffer from rat bait poison- but from the

grow lights- so the evidence in the video is all we have to make

a deduction- could be relevant if found to be a pattern latter

on- best to include it even though my assessment may be pure

conjecture- I can’t prove what killed this owl--- your call:

[link to Brought to you by RAT Bait Poison/DEAD BARN

OWL 7.22.19]

Mahalo! My sentence structure is not great- plenty of errors on

my end- but that’s fine - you captured my points- well done.

Your work is appreciated.

Mr. Berg approved interview summary via email 3 October

2019: There is one change--- DOFAW---- is: Division of

Forestry and Wildlife- under DLNR.

This concludes my review of the submission- however, omitted

from it- is that nearby - is the Honouliuli Internment Camp US

National Park Service development-

“Who conducted the survey for pueo and bats for that project-

if executed already?”

I can’t find status on that--- to then include that subject for

comment-

Revised Letter and Figures sent via email 3 January 2020

Mr. Berg replied via email 3 January 2020: Yes- I have issues

on the changes - it appears the expansion to the south

encroaches upon the gulch area- and or rather erodes any

current foliage buffer of the gulch that is provided to wildlife--

this buffer appears to be taken /consumed by the project---

Cultural Surveys Hawai‘i Job Code: HONOULIULI 172 Community Consultation

CIA

for the West Oahu Solar Project, Honouliuli, ‘Ewa, O‘ahu

TMK: [1] 9-2-002:007

112

Name

Affiliation

Comment

Berg, Tom

(cont.)

Former

Councilman,

District 1

How long do I have until the deadline to get you comments on

this notice?

Why is it necessary to encroach upon the gulch?

Is there an explanation?

Who did the biological survey for this project- or will there be

one in the future before development?

CSH replied via email 7 January 2020: The client has provided

answers to your questions regarding the gulch area and the

biological survey for the proposed project.

AES does not intend to build any project facilities within the

gulch along the southern boundary; however, the project area

boundary has been adjusted to provide flexibility for natural

features such as landscaping if warranted (either for visual

screening purposes or in response to specific comments

received as part of the cultural impact assessment). The

preliminary project plans include maintenance of a natural

vegetative buffer along the gulch.

As part of the due diligence studies for the project, a general

biological survey was conducted by Tetra Tech. In addition,

surveys have been conducted specifically for pueo based on the

protocol defined for The Pueo Project. Consistent with your

previous input, the team has consulted with the State of Hawaii

Department of Land and Natural Resources Division of

Forestry and Wildlife (DOFAW) as well as researchers with

The Pueo Project. This information will be detailed in the Draft

Environmental Assessment, which is expected to be published

in early 2020.

Mr Berg replied via email 8 January 2020: I don’t see any

reference to any studies from Project Pueo being conducted on

the property in question- do you?

Please take a gander- see files attached [Mr. Berg attached

pdfs of The Pueo Project Final Report April 2017-March 2018;

The Pueo Project Annual Report 2018; xcel file of UHWO

pueo survey data] if can- what do you conclude?

Was there a separate commissioned exercise conducted for the

solar area not in these reports- ?

CSH replied via email 10 January 2020: Thank you for

forwarding the attachments - we agree that the Pueo Project

data do not appear to include surveys within the project area.

The pueo surveys conducted within the project area, as

referenced in our previous response, were not conducted by

Pueo Project researchers as part of their research project.

Rather, these were conducted as part of the due diligence

efforts for the proposed solar project. These surveys were

Cultural Surveys Hawai‘i Job Code: HONOULIULI 172 Community Consultation

CIA

for the West Oahu Solar Project, Honouliuli, ‘Ewa, O‘ahu

TMK: [1] 9-2-002:007

113

Name

Affiliation

Comment

Berg, Tom

(cont.)

Former

Councilman,

District 1

conducted by qualified biologists according to the protocol that

was established for the Pueo Project (see Appendix 1 of the

Final Report); DOFAW specifically references this protocol as

the best methodology for pueo surveys. The results of these

surveys will be included in the Draft Environmental

Assessment, which is expected to be published in early 2020.

Mr. Berg replied via email 10 January 2020: Ok- mahalo-

Bond, John

Kanehili Cultural

Hui

Letter and Figures sent via USPS 14 May 2019

Letter and Figures sent via USPS 27 June 2019

Mr. Bond replied via telephone on 28 June 2019 requesting

letter and figures via email

CSH followed up with Mr. Bond via email 6 August 2019

Revised Letter and Figures sent via USPS 3 January 2020

Caceras,

Mana

Kaleilani

OIBC

Representative

for ‘Ewa

Letter and Figures sent via email 15 May 2019

Letter and Figures sent via email 28 June 2019

Mr. Caceras replied via email on 13 August 2019: E kala mai

for not responding to your earlier request, been in the field

quite a bit lately. I do not personally know of any mo‘olelo or

cultural sites within the proposed project area but here is a

short list of people who might. A few months ago I sat in a

section 106 consultation for the Makakilo Drive Extension

Project and these three gentlemen have so much knowledge of

the area.

Mr. Joseph Kūhiō Lewis, President, Kapolei Community

Development Corporation

Mr. Shad Kane, President, Kalaeloa Heritage and Legacy

Foundation and Aha Moku Representative

Mr. Douglas “McD” Philpotts, Hawaiian Cultural

Practitioner

Have a great evening.

CSH replied via email 14 August 2019

Revised Letter and Figures sent via email 3 January 2020

Mr. Caceras replied via email 15 January 2020: Mahalo Kellen.

Will look through the document and let you know if we have

any information that could be useful to your CIA.

Have a great weekend

CSH replied via email 23 January 2020

Cayan,

Phyllis

Intake Specialist,

SHPD

Letter and Figures sent via email 15 May 2019

DLNR.Intake.SHPD replied via email on 20 May 2019: Aloha,

your submittal is in the queue for review by the History &

Culture Branch and is assigned log 2019.01148 for reference.

Direct all inquiries on this matter to Regina Hilo and Hinano

Rodrigues at their emails above.

Cultural Surveys Hawai‘i Job Code: HONOULIULI 172 Community Consultation

CIA

for the West Oahu Solar Project, Honouliuli, ‘Ewa, O‘ahu

TMK: [1] 9-2-002:007

114

Name

Affiliation

Comment

Revised Letter and Figures sent via email 3 January 2020

Cordy, Ross

Professor of

Hawaiian-Pacific

Studies,

University of

Hawai‘i

(UHWO)

Letter and Figures sent via email 15 May 2019

Letter and Figures sent via email 28 June 2019

Revised Letter and Figures sent via email 3 January 2020

Cox, Malia

DHHL

CSH contacted Ms. Cox via email 16 September 2019: My

name is Kellen Tanaka. I am a cultural researcher with

Cultural Surveys Hawaii (CSH) and have been assisting with

the cultural impact assessment for the AES West O‘ahu Solar

Plus Storage Project. We were forwarded DHHL’s comments

for the pre-assessment for the Environmental Assessment for

the AES West O‘ahu Solar Project. We would like to follow up

with DHHL’s recommendations of consulting with Hawaiian

Homestead community associations and Native Hawaiian

Organizations. In the letter, it states there are six Hawaiian

Homestead communities less than three miles from the

proposed project. We have reached out to the Kanehili

Hawaiian Homestead Association, Kapolei Community

Development Corporation, Kaupea Homestead Association,

and the Malu‘ohia Residents Association which were

mentioned in the letter. Could you assist us in identifying the

other two Hawaiian Homestead communities and contact

information so we may reach out to them?

Ms. Cox replied via email 17 September 2019:

Kauluokahai Is

the newest community.

I don’t know that they have stood up a

association at this time.

KCDC might be able to help with

identifying appropriate individuals in that community.

Ill get back to you tomorrow on the remaining organization. I

believe it is the undivided interests group, but will have to

check my notes when I get back into the office tomorrow.

Ms. Cox replied via email 18 September 2019:

Attached, please

find a copy of a portion of the latest lease report submitted to the

HHC commission on 9/16/19. I’ve highlighted the communities

identified on the report.

Hoolimalima lessees are part of

Maluohai resident community. If you

need more information

about the communities, please contact homestead services

division (HSD)

Revised Letter and Figures sent via email 3 January 2020

Crabbe,

Kamanaʻo-

pono

Ka Pouhana of

OHA

Letter and Figures sent via USPS 14 May 2019

Letter and Figures sent via USPS 27 June 2019

Cultural Surveys Hawai‘i Job Code: HONOULIULI 172 Community Consultation

CIA

for the West Oahu Solar Project, Honouliuli, ‘Ewa, O‘ahu

TMK: [1] 9-2-002:007

115

Name

Affiliation

Comment

Cullen, Ty

J.K.

Representative,

House District 39

Letter and Figures sent via USPS 14 May 2019

Letter and Figures sent via email 15 May 2019

Letter and Figures sent via email 28 June 2019

Revised Letter and Figures sent via email 3 January 2020

DaMate,

Leimana

Executive

Director, DLNR-

Aha Moku

Letter and Figures sent via USPS 14 May 2019

Letter and Figures sent via email 15 May 2019

Letter and Figures sent via email 28 June 2019

Revised Letter and Figures sent via email 3 January 2020

Ms. DaMate replied via email 8 January 2020: Mahalo for

contacting the Hawaii State Aha Moku and I would

be happy to

forward your request to our Aha Moku Representative Shad

Kane, to whom I am encouraging a response to your email.

Aside from being a historian of Ewa, and Honouliuli

Ahupua’a, Shad is also in contact with generational cultural

practitioners from the ahupua’a, including Kehaulani Lum (to

whom I have also copied this email). I have also included

Rocky Kaluhiwa, the Aha Moku Advisory Committee (AMAC)

Chairperson for the State of Hawaii so she is aware of the

activities on O’ahu. Rocky is also the AMAC rep for the Island

of O’ahu. I am confident that between the three of these

practitioners, you will be able to get answers and guidance for

your project. Please feel free to contact me should you have

any questions or concerns.

CSH replied via email 9 January 2020

De Santos,

Kahulu

Cultural Advisor,

Aulani, A Disney

Resort and Spa

Letter and Figures sent via USPS 14 May 2019

Letter and Figures sent via USPS 27 June 2019

Revised Letter and Figures sent via USPS 3 January 2020

Eaton,

Ku‘uwainani

Hoakalei Cultural

Foundation

Letter and Figures sent via USPS 14 May 2019

Mail returned 17 May 2019

Farden,

Hailama

President,

Association of

Hawaiian Civic

Clubs

Letter and Figures sent via USPS 14 May 2019

Letter and Figures sent via email 15 May 2019

Letter and Figures sent via email 28 June 2019

Revised Letter and Figures sent via email 3 January 2020

Faulker,

Kirsten

Executive

Director, Historic

Hawai‘i

Foundation

Letter and Figures sent via USPS 28 May 2019

Letter and Figures sent via email 28 June 2019

Revised Letter and Figures sent via email 3 January 2020

Hanohano,

Anolani

Kānehili

Hawaiian

Homestead

Letter and Figures sent via email 15 May 2019

Letter and Figures sent via email 28 June 2019

Revised Letter and Figures sent via email 3 January 2020

Cultural Surveys Hawai‘i Job Code: HONOULIULI 172 Community Consultation

CIA

for the West Oahu Solar Project, Honouliuli, ‘Ewa, O‘ahu

TMK: [1] 9-2-002:007

116

Name

Affiliation

Comment

Hilo, Regina

Burial Sites

Specialist, SHPD

Letter and Figures sent via email 15 May 2019

Letter and Figures sent via email 28 June 2019

Ms. Hilo replied via email 28 June 2019: Mahalo nui for

sharing this. I’ll forward to my colleagues.

CSH replied via email 28 June 2019

Revised Letter and Figures sent via email 3 January 2020

Holt

Takamine,

Victoria

Executive

Director, PA‘I

Foundation

Letter and Figures sent via USPS 14 May 2019

Letter and Figures sent via email 15 May 2019

Letter and Figures sent via email 28 June 2019

Revised Letter and Figures sent via email 3 January 2020

Gabbard,

Mike

Senatorial

District 20

Letter and Figures sent via USPS 14 May 2019

Letter and Figures sent via email 15 May 2019

Senator Gabbard replied via email 15 May 2019: Mahalo for

the information.

CSH replied via email 9 July 2019

Revised Letter and Figures sent via email 3 January 2020

Ito, Wallace

K.

KUA

Ewa Limu

Project

Letter and Figures sent via email 22 May 2019

CSH followed up with Mr. Ito via email 6 August 2019

Mr. Ito replied via email 21 August 2019: Sorry for not

following through sooner. I just forwarded your request to

other organizations doing malama ‘aina work in the Ewa

Moku. You are cc’d on that so you should have received it a

few minutes ago.

CSH replied via email 21 August 2019

Revised Letter and Figures sent via email 3 January 2020

Kai, G. Umi

President, ʻAha

Kāne

Letter and Figures sent via USPS 14 May 2019

Letter and Figures sent via email 15 May 2019

Letter and Figures sent via email 28 June 2019

Revised Letter and Figures sent via email 3 January 2020

Kaleikini,

Ali‘ikaua

Cultural

descendant

Letter and Figures sent via USPS 14 May 2019

Letter and Figures sent via USPS 27 June 2019

Revised Letter and Figures sent via USPS 3 January 2020

Kaleikini,

Hāloa

Cultural

descendant

Letter and Figures sent via USPS 14 May 2019

Letter and Figures sent via USPS 27 June 2019

Revised Letter and Figures sent via USPS 3 January 2020

Kaleikini,

Kala

Cultural

descendant

Letter and Figures sent via USPS 14 May 2019

Letter and Figures sent via USPS 27 June 2019

Revised Letter and Figures sent via USPS 3 January 2020

Kaleikini,

Mahiamoku

Cultural

descendant

Letter and Figures sent via USPS 14 May 2019

Letter and Figures sent via USPS 27 June 2019

Revised Letter and Figures sent via USPS 3 January 2020

Cultural Surveys Hawai‘i Job Code: HONOULIULI 172 Community Consultation

CIA

for the West Oahu Solar Project, Honouliuli, ‘Ewa, O‘ahu

TMK: [1] 9-2-002:007

117

Name

Affiliation

Comment

Kaleikini,

Moehonua

Cultural

descendant

Letter and Figures sent via USPS 14 May 2019

Letter and Figures sent via USPS 27 June 2019

Revised Letter and Figures sent via USPS 3 January 2020

Kaleikini,

No‘eau

Cultural

descendant

Letter and Figures sent via USPS 14 May 2019

Letter and Figures sent via USPS 27 June 2019

Revised Letter and Figures sent via USPS 3 January 2020

Kaleikini,

Paulette

Ka‘anohi

Cultural

descendant

Letter and Figures sent via USPS 14 May 2019

Letter and Figures sent via email 15 May 2019

Letter and Figures sent via USPS 27 June 2019

Letter and Figures sent via email 28 June 2019

Revised Letter and Figures sent via USPS 3 January 2020

Revised Letter and Figures sent via email 3 January 2020

Kaleikini,

Tuahine

Cultural

descendant

Letter and Figures sent via USPS 14 May 2019

Letter and Figures sent via USPS 27 June 2019

Revised Letter and Figures sent via USPS 3 January 2020

Kane, Shad

‘Ewa Moku

Representative,

Aha Moku;

Kalaeloa

Heritage and

Legacy

Foundation

Letter and Figures sent via USPS 14 May 2019

Letter and Figures sent via email 15 May 2019

Letter and Figures sent via email 28 June 2019

CSH spoke with Mr. Kane via telephone 13 August 2019:

Mr.

Kane stated that he is not in oppositio

n to the proposed project.

He noted the project area has been previously disturbed by sugar

cane production.

Revised Letter and Figures sent via email 3 January 2020

Kanekoa,

Mikiala

Hālau ‘o

Kaululaua‘e

Letter and Figures sent via USPS 14 May 2019

Letter and Figures sent via email 15 May 2019

Letter and Figures sent via email 28 June 2019

Revised Letter and Figures sent via email 3 January 2020

Kauahi, R.

Kaiulani

Vincent

Culture and Arts

Coordinator,

Dept. Parks and

Recreation

Letter and Figures sent via USPS 14 May 2019

Mail returned 17 May 2019

Keala, Jalna

Association of

Hawaiian Civic

Clubs

Letter and Figures sent via USPS 14 May 2019

Letter and Figures sent via email 15 May 2019

Letter and Figures sent via email 28 June 2019

Revised Letter and Figures sent via email 3 January 2020

Keaulana,

Ha‘a

Cultural Advisor

at Four Seasons

Resort at Koolina

Letter and Figures sent via USPS 14 May 2019

Mail returned 17 May 2019

Keli‘inoi,

Kalahikiola

Cultural

descendant

Letter and Figures sent via USPS 14 May 2019

Letter and Figures sent via USPS 27 June 2019

Revised Letter and Figures sent via USPS 3 January 2020

Cultural Surveys Hawai‘i Job Code: HONOULIULI 172 Community Consultation

CIA

for the West Oahu Solar Project, Honouliuli, ‘Ewa, O‘ahu

TMK: [1] 9-2-002:007

118

Name

Affiliation

Comment

Keli‘inoi,

Kilinahe

Cultural

descendant

Letter and Figures sent via USPS 14 May 2019

Letter and Figures sent via USPS 27 June 2019

Revised Letter and Figures sent via USPS 3 January 2020

Kruse,

Kehaulani

Outrigger

Enterprises,

Cultural Advisor

Letter and Figures sent via USPS 14 May 2019

Letter and Figures sent via email 15 May 2019

Letter and Figures sent via email 28 June 2019

Revised Letter and Figures sent via email 3 January 2020

Lee, Mike

Kumukauoh

a

Kanehili Cultural

Hui

Letter and Figures sent via USPS 14 May 2019

Letter and Figures sent via email 15 May 2019

Letter and Figures sent via email 28 June 2019

Legal, Jack

Chair, Makakilo/

Kapolei/Honokai

Hale

Neighborhood

Board No. 34

Letter and Figures sent via USPS 14 May 2019

Letter and Figures sent via USPS 27 June 2019

Revised Letter and Figures sent via USPS 3 January 2020

Lewis,

Joseph

Kūhiō

President,

Kapolei

Community

Development

Corporation

Letter and Figures sent via USPS 14 May 2019

Letter and Figures sent via email 15 May 2019

Letter and Figures sent via email 28 June 2019

Revised Letter and Figures sent via email 3 January 2020

Lidstone,

Miki‘ala

Executive

Director, Ulu A‘e

Learning Center

Letter and Figures sent via USPS 14 May 2019

Letter and Figures sent via email 15 May 2019

Letter and Figures sent via email 28 June 2019

Revised Letter and Figures sent via email 3 January 2020

Lilomaiava-

Doktor,

Sa‘iliemanu

Associate

Professor of

Hawaiian-Pacific

Studies,

University of

Hawai‘i

(UHWO)

Letter and Figures sent via email 15 May 2019

Letter and Figures sent via email 28 June 2019

Revised Letter and Figures sent via email 3 January 2020

Lopez,

Kealii

Imua Hawaii

Letter and Figures sent via USPS 14 May 2019

Letter and Figures sent via email 15 May 2019

Letter and Figures sent via email 28 June 2019

Revised Letter and Figures sent via email 3 January 2020

Cultural Surveys Hawai‘i Job Code: HONOULIULI 172 Community Consultation

CIA

for the West Oahu Solar Project, Honouliuli, ‘Ewa, O‘ahu

TMK: [1] 9-2-002:007

119

Name

Affiliation

Comment

Luthy,

Tamara

Ethnographer,

DLNR

Letter and Figures sent via email 28 June 2019

Ms. Luthy responded via email 1 July 2019: Good to hear from

you! Thank you for letting me know about the project. I am

cc’ing Kaahiki Solis and Hinano Rodrigues on this email. We

request that when you finish your CIA that we may receive a

copy as a professional courtesy so that we can keep it for our

records in case any other archaeological, architectural, or

ethnographic work in the same or adjourning regions comes

through our office for review. I have also attached a few

reports which may be of interest from the Ewa/Honouliouli

area, though I didn’t see anything from the exact TMK your

project is in.

SHPD policy dictates that we can only recommend ways to find

research participants rather than pointing you to specific

individuals. I would recommend putting out a notice in the

Honolulu Star Advertiser, notifying OHA as well to see if

anyone there can send out the information to relevant parties.

It would be useful to follow up with any Hawaiian civic clubs

in the area. It may be worthwhile to contact folks involved with

the Ewa Limu Project, as they may know local resource users

both mauka and makai. There is also an interview with Julia

Powell and also one with Louis Aila Junior through the UH

Oral History Project which discuss life in Ewa in the past,

including some information on gathering plants. If you want to

know more about ongoing gathering practices in the area, it

would be worthwhile to reach out to local hula halaus and

lā‘au lapa‘au practitioners. Hawaiian Studies and/or

professors at UH Manoa and Leeward Community College

may be good resources as well.

CSH replied via email 3 July 2019:

Mahalo for your quick

response and all the information you provided. Those pdfs are

very helpful. We will continue our outreach with those mentioned

below. . .

Revised Letter and Figures sent via email 3 January 2020

Ms. Luthy replied via email 3 January 2020: Hi there Kellen, I

just got your email. I will look into it on Monday and get back

to you soon.

CSH replied via email 6 January 2020

Lyman,

Melissa

Kalaeloa

Heritage and

Legacy

Foundation,

President

Letter and Figures sent via USPS 14 May 2019

Letter and Figures sent via email 15 May 2019

Letter and Figures sent via email 28 June 2019

Revised Letter and Figures sent via email 3 January 2020

Cultural Surveys Hawai‘i Job Code: HONOULIULI 172 Community Consultation

CIA

for the West Oahu Solar Project, Honouliuli, ‘Ewa, O‘ahu

TMK: [1] 9-2-002:007

120

Name

Affiliation

Comment

Malama,

Tesha

‘Ewa Villages

Association

Letter and Figures sent via USPS 14 May 2019

Letter and Figures sent via USPS 27 June 2019

Revised Letter and Figures sent via USPS 3 January 2020

McKeague,

Kawika

Cultural

practitioner,

Honouliuli

historian and

longtime resident

Letter and Figures sent via USPS 9 August 2019

Revised Letter and Figures sent via email 3 January 2020

Medeiros,

Pōhai

PIKO Program

Advisor,

University of

Hawai‘i West

O‘ahu

Letter and Figures sent via USPS 9 August 2019

Revised Letter and Figures sent via email 3 January 2020

Nahulu-

Mahelona,

Moani

Hawaiian Studies

Department,

Kapolei HS

Letter and Figures sent via USPS 14 May 2019

Letter and Figures sent via USPS 27 June 2019

Revised Letter and Figures sent via USPS 3 January 2020

National

Park Service

Honouliuli

National

Monument

Letter and Figures sent via USPS 14 May 2019