HAL Id: hal-02619286

https://uca.hal.science/hal-02619286

Preprint submitted on 25 May 2020

HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access

archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci-

entic research documents, whether they are pub-

lished or not. The documents may come from

teaching and research institutions in France or

abroad, or from public or private research centers.

L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est

destinée au dépôt et à la diusion de documents

scientiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non,

émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de

recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires

publics ou privés.

Have unequal treaties fostered domestic market

integration in Late Imperial China ?

Jean-Louis Combes, Mary-Françoise Renard, Shuo Shi

To cite this version:

Jean-Louis Combes, Mary-Françoise Renard, Shuo Shi. Have unequal treaties fostered domestic mar-

ket integration in Late Imperial China ?. 2020. �hal-02619286�

C EN T R E D 'ÉTU D ES

E T D E R EC H E R CH E S

S U R LE DE V E L O PP E ME N T

I NT E R NA TI O NA L

SÉRIE ÉTUDES ET DOCUMENTS

Have unequal treaties fostered domestic market integration in

Late Imperial China?

Jean-Louis Combes

Mary-Françoise Renard

Shuo Shi

Études et Documents n° 4

May 2020

To cite this document:

Combes J.-L., Renard M.-F., Shi S. (2020) “Have unequal treaties fostered domestic market

integration in Late Imperial China ? ”, Études et Documents, n° 4, CERDI.

CERDI

POLE TERTIAIRE

26 AVENUE LÉON BLUM

F- 63000 CLERMONT FERRAND

TEL. + 33 4 73 17 74 00

FAX + 33 4 73 17 74 28

http://cerdi.uca.fr/

Études et Documents n° 4, CERDI, 2020

2

The authors

Jean-Louis Combes

Professor, School of Economics, University of Clermont Auvergne, CNRS, CERDI-IDREC, F-

63000 Clermont-Ferrand, France.

Email address: [email protected]

Mary-Françoise Renard

Professor, School of Economics, University of Clermont Auvergne, CNRS, CERDI-IDREC, F-

63000 Clermont-Ferrand, France.

Email address: m-[email protected]

Shuo Shi

PhD Candidate in Economics, Fudan University, CCES, China.

Email address: [email protected]

Corresponding author: Mary-Françoise Renard

This work was supported by the LABEX IDGM+ (ANR-10-LABX-14-01) within the

program “Investissements d’Avenir” operated by the French National Research Agency

(ANR).

Études et Documents are available online at: https://cerdi.uca.fr/etudes-et-documents/

Director of Publication: Grégoire Rota-Graziosi

Editor: Catherine Araujo-Bonjean

Publisher: Mariannick Cornec

ISSN: 2114 - 7957

Disclaimer:

Études et Documents is a working papers series. Working Papers are not refereed, they constitute

research in progress. Responsibility for the contents and opinions expressed in the working papers

rests solely with the authors. Comments and suggestions are welcome and should be addressed to the

authors.

Études et Documents n° 4, CERDI, 2020

3

Abstract

The objective of the paper is to study the relationship between international trade openness

and domestic market integration in Late Imperial China. More specifically, we focus on a

natural experiment namely the Unequal Treaties of the second half of the nineteenth century

that lifted the long-existing international trade restriction system.

The integration of domestic markets is analyzed while looking at the existence of a long term

common movement in the grain prices between provinces. The econometric results show that

trade openness did not lead to better integration of the Chinese domestic grain markets. Our

results support the hypothesis according to which long-distance trade has not generated

efficiency gains in domestic markets. We evidence a strong segmentation between domestic

and international grain markets owing to different traded products and operators.

Keywords

Market integration, Law of one prices, Late Imperial China.

JEL Codes

F15, N75.

One of the main characteristics of China’s development is the mixing of political

centralization and economic decentralization. It may result in fragmentation and

inequalities across China’s provinces. This situation has expanded since the reform and

open-up strategy was adopted in 1978, with trade and investment policies being

concentrated in coastal provinces in a first time. More generally, the Chinese case raises

a more general question concerning the relationship between trade openness and

domestic market integration. Are the two dynamics independent or complementary?

Does trade openness generates positive spillovers between external and domestic trade?

In a country as large and geographically diverse as China, the topic of provincial market

integration is crucial for understanding the movements of production factors and their

impact on economic growth. This paper investigates the historical integration of

China’s domestic markets. In contrast to the existing literature, we examine this market

integration in the perspective of international trade environment. Specifically, we study

the impact of the unequal treaties signed during the 19

th

century and at the beginning of

the 20

th

century between the Qing dynasty (1644–1912) and foreign powers on the

domestic market integration. These unequal treaties have led, among other things, to

trade openness. Thus, they can be seen as a natural experiment highlighting the impact

of trade openness on domestic market integration.

More precisely, this paper econometrically evaluates domestic grain market integration

before and after the unequal treaties. The Law of One price (LOP) in late imperial China

(1736–1911) using the maximum likelihood (ML) method of cointegration developed

by Johansen (1988) and Johansen and Juselius (1990) is thus tested. In addition, a

robustness test based on price sigma convergence is implemented. It appears mainly

that the unequal treaties have not led to a better integration of domestic cereal markets.

They remain fundamentally fragmented in late imperial China. In the first section, we

will explain the potential links between unequal treaties and the domestic market

integration. In the second one, we will present the methodology and the data and in the

Études et Documents n° 4, CERDI, 2020

4

third one, we will give and comment the results.

1 - Unequal treaties and domestic market integration

Economic development has often been linked to market integration. This means there

are strong relationships between different regions in a country that lead to prices

convergence, the so-called “Law of One price” (LOP). The consequence is that one

region depends on the situation of the other ones, more than its own history (Marshall,

1920). There are no or few economic restrictions on the mobility of goods and services,

production factors and persons between them (Tinbergen, 1965).

This relationship has been used to understand why China did not face an industrial

revolution as in Europe, with the hypothesis that market integration is an indicator of

economic efficiency and more generally of development. During a long time, the

underdevelopment in China, despite the unified political system was supposed to induce

less integrated markets than in Europe and then explain the lag between the both. This

idea has been weakened mainly by Pomeranz (2000) who suggested that China’s

markets during the 18

th

century were closer to the markets described in the neo-classical

model than European ones. Shiue and Keller (2007) provided empirical support by

studying 121 prefectural markets. However, these results have been challenged by other

studies concluding on a disintegration of markets in Northern as well as Southern

Chinese regions (Bernhofen and al., 2015, 2017, Gu and Kung, 2019).

China’s situation is very specific under the Qing dynasty (1644–1912). At the beginning

of the period we are interested in, the Qing dynasty had good economic results, a

territorial expansion and a growing population, from 138 million in 1700 to 381 million

in 1820 and 430 in 1850, and an economic growth stronger than the Japanese one

(Maddison, 2007). Political centralization was strong with a multi-level bureaucratic

hierarchy. Nevertheless, with an increasing population and without substantial

Études et Documents n° 4, CERDI, 2020

5

improvement in agricultural productivity, market integration decreased after 1776 (Gu,

2013). Several rebellions weakened the government, the more important being the

Taiping Rebellion (1850–1864). At its peak, the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom controlled

16 provinces most of which were the major tax revenue sources of the central

government. To fight against this rebellion, the central government created a new type

of army, which involved a strong delegation of power to the provincial authorities

(Maddison, 2007). It has been very costly. The authorities could not anymore pay for

the hydraulic structures, the banks of the Yellow River had been abandoned and it was

impossible to use it to send grains to Beijing (Maddison, 2007). Then to increase it

income, the government implemented a new tax, Lixin Tax, at the provincial level.

“Political boundaries determine market size when commodity circulation is restricted

by taxation, trade policies, and currency” (Gu, 2013, p.73). Brandt et.al. (2014) consider

economic failure is due to an imperial institutional system that protected vested interests,

as the local gentry. The revolts happening during this period induced a decrease in the

level of standard of the population and the whole economic system has been weakened

or collapsed during the treaties period.

Before the Qing Dynasty, China has been engaging in foreign trade since a long time,

mainly with proximate countries mostly in Asia (Keller et.al., 2011). In the Ming

Dynasty (1368–1644), tributary trade was accepted but controlled by the central

government, or Chaoting, with stringent restrictions. Although the Qing dynasty

adopted restrictive trade policy, several provinces were still allowed to maintain

authorized coastal ports to international trade. In 1685, four customs were set up in the

city of Canton (Guangdong Province), Xiamen (Fujian Province), Ningbo (Zhejiang

Province), and Songjiang (Jiangsu Province) to regulate trade with foreign merchants.

In the second half of the reign of Emperor Kangxi (1662–1722), foreign merchant ships

were allowed to trade with China at all the ports specified. Trade regulation evolved

into the Canton System (1757–1842) under which all the trade with the West was only

allowed on the southern port of Canton (now Guangzhou) (Van Dyke, 2005). Foreign

Études et Documents n° 4, CERDI, 2020

6

trade was restricted, and rice exports were prohibited.

Since the mid-19

th

century, however, the Canton System gradually vanished: the

unequal treaties between the Qing government and the West knocked off the long-term

trade restriction in China. As the result of military failure in the Opium War (1840–

1842), China was forced to sign the Treaty of Nanjing (1842). It abolished the

traditional tributary system, liberalised the highly regulated trading system, legalizing

the opium trade and opened additional ports to foreign trade. In addition to Guangzhou

and the four treaty ports

1

opened to foreign trade and residence by the Treaty of

Nanjing, more provinces in China were opened to foreign merchants by the following

treaties. Based on the Treaty of Tianjin (1858), China opened Tainan, Haikou, Shantou,

Haicheng, Nanjing, Penglai, Tamsui, Yantai, and Yingkou. The Convention of Beijing

(1860) legalised Tianjing as a trade port. By the Traité de Paix (1885), Baosheng and

Liangshan were opened. By the Treaty of Shimonoseki (1895), Shashi, Chongqing,

Suzhou, and Hangzhou were opened to Japan. Therefore, most of Chinese provinces

succumbed and opened trading ports to major industrial countries. Less regulated trade

environment often improves, theoretically, market integration, though it takes a rather

long historic process.

With new industrial enterprises in the ports, we could consider they need to increase

the demand and then facilitate transportation. Several studies have been devoted to the

relationships between transport costs and trade (Anderson and van Wincoop, 2004).

With the invention of railways at the beginning of the 19

th

century, the transport costs

which are one of the main obstacle to trade, decreased a lot in Europe, 36% in France

between 1841 and 1851 (Caron, 1997). This resulted in an integration of markets and a

spatial concentration of activities. This integration is very dependent on the quality of

1

The four treaty ports were Amoy in Xiamen, Foochowfoo in Fuzhou, Ningpo, and Shanghai.

Études et Documents n° 4, CERDI, 2020

7

infrastructures and its deterioration has a strong impact on trade (Limao and Venables,

2001). In the case of China, the openness arising from the treaties gave the opportunity

for foreigners to produce in China and to trade with the mainland. Therefore, it should

be an opportunity to invest in infrastructures, which could decrease transaction costs

and fuel domestic market integration. Profit opportunities in international trade could

have encouraged both private agents and the Chinese state to promote domestic trade

(improvement of transport and communication infrastructure, payment system,

commercial law,..).

However, this virtuous dynamic may not manifest for two reasons: if people involved

in domestic trade and in international trade are not the same and if the goods traded

internationally are different of those traded in domestic markets. The first reason rests

on the opposition between on the one hand, merchants, which are active in the ports,

would be more interested by international trade and on the other hand, officials would

be more concerned about domestic trade. Their main objective could be to ensure a

regular supply of necessities (grains,…) to urban markets to avoid social and political

troops. There is a traditional opposition between government and the administration

interested in the inland country and some merchants, interested in trade and in

technological progress. The ports affected by the treaties are usually considered as

“enclaves of modernity” and it is not relevant for the other cities, and even less for the

rest of the country; China’s agriculture has not been significantly concerned by the

openness of the country (Maddison, 2006). China’s firms were family ones and

domestic trade was not based on legal contracts, but was part of the social relationships,

which determined the social life: relationships between individuals, bonds of friendship,

family commitments… (Fairbank and Goldman, 2010). Then, “the insertion of a treaty

port economy in the traditional Chinese empire represented initially what seemed like

a small rupture to a giant closed political system” (Brandt et.al., 2014, p.81).Without

any modern constitution or commercial law, a small number of Western-style

enterprises hardly overthrew one ounce of the dominant traditional mentality. An

Études et Documents n° 4, CERDI, 2020

8

example reflects the institutional barriers that existed at that time. When the British firm

Jardine Matheson established a steam-powered silk filature in Shanghai during the

1860s, they prepared for “their inability to obtain prompt and efficient delivery and

storage of cocoons in the immediate rural hinterland outside treaty port (Brandt et.al.,

2014, p.83). The frontier between the modern institutions in the treaty ports and the

traditional ones (including informal monopolies and the guild system) was quite strong.

Until the mid-20

th

century, China had an ethnocentric vision of the world because of its

ideology, mentalities and educational system (Maddison, 2006). It seems that local

markets were vibrant, but trade was cut off between regions (Rawsky, 1972).

The second reason for the lack of virtuous cycle between openness and market

integration may be due to the opposition between internationally tradable goods and

domestically tradable ones. First, we must notice that China’s trade openness was less

important than in some similar countries. In 1870, China’s exports accounted for 5.6

per cent of Asian and Western exports, and 3.9 in 1913. For the same years, India’s

trade accounted for 13.9 and 8.8 per cent (Maddison, 2006). Large countries are often

less opened than small ones, but it may not explain the difference between these two

large countries. China’s foreign trade policy has often been restrictive, allowing limited

exchange between domestic and foreign traders in specific areas (Keller et.al., 2011).

The tradition of a lack of interest for foreign products from the government is well

known. It reflects the nationalism and the wish of self-sufficiency, but also a kind of

reality. It is reported than in the 1830s the Chinese native nankeen cotton cloth was

superior in quality and cost compared to Manchester cotton goods (Greenberg, cited by

Keller et. al., 2011). In 1890, agriculture represented 68.5 per cent of GDP and

handicraft 7.7 per cent (Maddison, 2007). Exports are mainly composed of tea and silk.

Imports are mainly devoted to opium (37 per cent in 1870), and cotton latter in the 20

th

century. Then China’s imports became more diversified after 1911. China did virtually

import no equipment or modern means of production, which could have been traded

domestically. Traditionally, it also imports luxury goods from Europe. These types of

Études et Documents n° 4, CERDI, 2020

9

products are dedicated to very few people in the population and may not be a vector for

market integration.

In either case, domestic markets in late imperial China would be more isolated than

integrated. Even though the unequal treaties forced China to open some ports,

introducing a friendly environment for price convergence, China's rigid social system

and autarkic economy might still impede domestic market integration. If so, the LOP is

unlikely to hold.

2- Data and methodology

As shown by Fackler and Goodwin (2001), market integration occurs when supply or

demand shocks in one region is partially or fully transmitted to another region. Market

integration is the subject of major studies insofar as it leads to efficiency gains and

ensures the inter-regional smoothing of shocks (e.g. Shiue, 2002). For markets to be

fully integrated, the LOP must hold. The LOP is a stronger assumption than market

integration. It indicates that price changes in a given location net of transaction costs

are perfectly transmitted to prices in other locations through trade. Arbitrage clears the

spatial price differences. Although the literature has highlighted the limitations of an

approach that relies exclusively on price data (e.g. Barrett & Li, 2002), in the lack of

sufficiently reliable data on quantities traded, the usual method for testing market

integration is to consider in the long-term price co movements between different

locations (Federico, 2012). Specifically, it is assumed that if prices diverge permanently,

then arbitrage opportunities are not fully exploited, and markets are not integrated.

To examine the market integration in late imperial China, we focus on grain prices that

was more marketized than other important staple commodities, such as maize, potato,

and sweet potato. In the eighteen century, accounting for roughly 40% of the gross

national product, 20% of China’s total grain output was traded between the provinces

Études et Documents n° 4, CERDI, 2020

10

of which the Yangtze region was the logistics center (Peng, 2006; Xu & Wu, 2000).

Grain was used by Shuie & Keller (2007), Li (2000), and Gu (2013) among others in

their work on market integration in historic China.

In the cointegration tests, we specifically use data on grain prices in 13 provinces in

late imperial China with a maximum period spanning from 1738 to 1911. The data are

obtained from Chen and Kung (2016).

2

The Qing government originally kept those

grain prices. Local officials reported grain prices to the central government each month.

Given that cropping patterns were different across regions in the Qing Dynasty, to

ensure comparability, we follow Chen and Kung (2016) and convert one “dan” of grain

(of various kinds) into the standardized kilocalories.

3

This conversion based upon

sources compiled by the Institute of Nutrition and Food Safety, Chinese Center for

Disease Control and Prevention (2002).

4

We then calculated the yearly average price

and adjusted the price according to purchasing power parity, which was 1,900 USD.

The deflator was obtained from Peng (2006).

Our utilization of grain prices from a nationally representative sample departs from the

seminal work by Shiue & Keller (2007) who select the southern and central regions of

China. Our sample is on province-level that deviates from the county-level sample used

by Gu (2013). Therefore, our focus is on market integration between provinces and not

within provinces. Indeed, long-distance trade is likely more affected by international

trade treaties than short-distance trade.

2

Their data on grain price is based on “Qing Dynasty’s Price of Food Database,” Institute of Modern History, the

Academia Sinica, Taiwan (http://mhdb.mh.sinica.edu.tw/foodprice/about.php), and “Grain Prices Data during

Daoguang to Xuantong of the Qing Dynasty”, Institute of Economics, Chinese Academy of Social Science (2010).

3

The dan is the unit of weight employed at the time. Each dan equals 83.5 kg.

4

The standard calories of various crops were obtained from Yang (1996).

Études et Documents n° 4, CERDI, 2020

11

Province Classification

In our sample, the 13 provinces are Fujian, Guangdong, Guangxi, Henan, Hubei, Hunan,

Jiangsu, Jiangxi, Shandong, Shanxi, Sichuan, Zhejiang, and Zhili. The sample is

constrained by the availability of consistent data for the period.

5

We classified the

provinces according to two rules: geographic location and overseas trade policy.

The geographic location was probably decisive in connecting domestic markets to

international trade in late imperial China. Coastal provinces with ports received price

information more conveniently through international trade activities and could be more

integrated. By contrast, markets in inland provinces would be less likely to be integrated

because grain prices in landlocked markets were determined by regional transactions

rather than their international counterparts. Therefore, we classify 12 provinces into

coastal and inland groups (see Table 1). Hubei is dropped in this classification because

its data is inconsistent with that of other inland provinces in study periods.

Table 1 Province Classification Based on Geographic Locations

Group

Provinces

Coastal

Fujian Guangdong Guangxi Jiangsu

Shandong Zhejiang Zhili

Inland

Henan Hunan Jiangxi Shanxi

Sichuan

Source: Authors’ classification.

Based on the opening timeline of each provincial trade port, we classify 13 provinces

into three groups, namely opened group, less-opened group, and closed group (see

Table 2). One province is classified as opened if ports there were opened by China, as

less opened if ports there were forced to open by the unequal treaties. It is noteworthy

5

In Chen and Kung (2016)’s dataset, there are 18 provinces. Among them, 13 provinces are used in our sample.

The five provinces that are not used in our sample are Anhui, Gansu, Guizhou, Shaanxi, and Yunnan.

Études et Documents n° 4, CERDI, 2020

12

that the provinces in the closed group had no ports opened by China or according to the

unequal treaties in our study period.

Table 2 Province Classification Based on Opening Policies

Group

Provinces

Opened

Fujian Guangdong Jiangsu Zhejiang

Less opened

Hubei Jiangxi Shandong Sichuan Zhili

Closed

Guangxi Henan Hunan Shanxi

Source: Authors’ classification.

Cointegration Test

We consider two local markets of a homogeneous good: grains. When trade happens,

the price in the importing market

is the sum of the price in the exporting market

and transaction costs

. The arbitrage condition would thus hold as

. The market integration relationship to be investigated is given as the following

equation under the assumption of stationary transaction costs:

1.

If , the LOP holds and the markets are fully integrated. If , the prices

tend to move in the same direction, but the markets are not fully integrated. However,

when the price series are non-stationary, the LOP cannot be tested by estimating this

regression (Engle & Granger, 1987). In this situation, cointegration tests are the

appropriate tool. The multivariate Johansen test (Johansen & Juselius, 1990) will be

used here since it allows for hypothesis testing on the parameters in the cointegration

vector and exogeneity tests. The Johansen test is based on a vector autoregressive error

correction model (VECM). If

denotes an ( ) vector of I(1) prices, then the kth-

order VECM is given by

2.

Études et Documents n° 4, CERDI, 2020

13

where

; ;

; each

of

is an matrix of parameters;

is an identically and independently

distributed n-dimensional vector of residuals with zero mean and variance matrix,

;

is a constant term; and is trend. Since

is I(1), but

and

variables

are I(0), equation (2) will be balanced if

is I(0). So, it is the matrix that

conveys information about the long-run relationship among the variables in

. The

rank of , , determines the number of cointegration vectors, as it determines how

many linear combinations of

are stationary. According to Stock and Watson (1988),

there will be different stochastic trends between the provincial prices series.

Consequently, could be interpreted as a proxy of the strength of market integration.

When , each provincial price follows its own trend and the degree of market

fragmentation is maximum. When , provincial markets are integrated,

but the LOP does not hold in the presence of at least two common stochastic trends.

When , there exist a unique common stochastic trend between all prices (and

all the pair-wise prices are cointegrated). The empirical question is therefore the extent

to which unequal treaties impact .

To examine the strength of market integration, , we propose two likelihood ratio test

statistics. The null hypothesis of at most cointegrating vectors against a general

alternative hypothesis of more than cointegrating vectors is tested by

3.

The null of cointegrating vector against the alternative of is tested by

4.

s are the estimated eigen values (characteristic roots) obtained from the matrix

Études et Documents n° 4, CERDI, 2020

14

and is the number of usable observations.

6

Robustness check: sigma price convergence

We check the robustness of the results of the cointegration tests by examining time

evolution of price convergences. Following Wolszczak-Derlacz (2008) which derives

the concept from the literature of real convergence, we define sigma convergence as

the evolution over time of the spatial dispersion of provincial prices. Sigma

convergence occurs when the price dispersion declines over time. Specifically, for each

year, the standard deviation of the grain price distribution between provinces is

calculated and presented in a graph. It must be checked whether unequal treaties lead

to a break in the price dispersion trend.

3- Results

The search for a common stochastic trend implies that all the price series are non-

stationary and integrated of the same order. For most province groups in our sample,

however, the price series are often found to be stationary by the results of unit root tests

for each group.

7

This limits our application of the cointegration tests to the geographic

location groups and opening policy groups with at least two price series integrated of

order one, or I(1).

Geographic Location Groups

Table 3 presents the cointegrations results of the geographic location groups. Both the

trace and -max tests show one cointegrating vector for Jiangsu and Shandong in the

6

For details, see Johansen & Juselius (1990).

7

The results of unit root tests are reported in the Appendix.

Études et Documents n° 4, CERDI, 2020

15

coastal group, 1741‒1806. This implies that the grain prices in Jiangsu and Shandong

contain the same stochastic trend and so are cointegrated. Since, there are only two

provinces in this group, the finding of cointegration suggests that the LOP holds for

grain markets in Jiangsu and Shandong before the 1860s. The cointegration results for

the remaining three groups indicate that the grain markets in the coastal group after

1860s, as well as in the inland group, are unintegrated: there is no common stochastic

trend

Table 3 Cointegration Results of the Geographic Location Groups

Eigen

Value

Trace test

Maximum eigen value test

Cointegration

LOP

Null

-trace

Null

-max

Coastal Group, 1741–1806 (lag = 1)

Guangdong and Zhejiang

0.324

**

30.390

***

24.678

Yes

Yes

0.087

5.712

5.712

Coastal Group, 1871‒1909 (lag = 1)

Fujian, Guangxi, and Zhili

0.373

36.011

18.200

No

No

0.265

17.812

12.016

0.138

5.796

5.796

Inland Group, 1743‒1814 (lag = 1)

Jiangxi and Sichuan

0.179

17.661

14.098

No

No

0.048

3.563

3.563

Inland Group, 1871‒1911 (lag = 2)

Jiangxi, Shanxi, and Sichuan

0.306

23.804

14.960

No

No

0.134

8.843

5.886

0.070

2.957

2.957

Notes: *** Significant at the 1% level. ** Significant at the 5% level. * Significant at the 10% level.

The optimal lag specification of the coastal group (1871‒1909) is selected by the Schwarz

information criterion (SIC). For other groups, the optimal lag specification is selected by the AIC.

Source: Authors’ calculation.

Opening Policy Groups

Table 4 presents the cointegration results of the opening policy groups. For Guangxi,

Hunan, and Shanxi in the closed group, 1871‒1908, both the trace and -max tests

Études et Documents n° 4, CERDI, 2020

16

reject the null hypothesis of none cointegrated vectors, revealing at least two vectors

common stochastic trends. This suggests that the LOP does not hold because the

common stochastic trend is not unique. By contrast, for the opened and less-opened

groups where trading port were opened by China or according to the unequal treaties,

little evidence is found for the existence of market integration in both the pre- and post-

1860s.

Table 4 Cointegration Results of the Opening Policy Groups

Eigen

Value

Trace test

Maximum eigen value test

Cointegration

LOP

Null

-trace

Null

-max

Opened Group, 1816‒1860 (lag = 1)

Guangdong and Zhejiang

0.320

23.408

16.580

No

No

0.147

6.828

6.827

Less-opened Group, 1871‒1910 (lag = 1)

Jiangxi and Sichuan

0.185

13.027

8.193

No

No

0.114

4.834

4.834

Closed Group, 1871‒1908 (lag = 1)

Guangxi, Hunan, and Shanxi

0.465

**

42.992

23.775

Yes

No

0.281

19.217

12.531

0.161

6.685

6.685

Notes: *** Significant at the 1% level. ** Significant at the 5% level. * Significant at the 10% level.

The optimal lag specification of the closed group (1871‒1908) is selected by the Schwarz information

criterion (SIC). For other groups, the optimal lag specification is selected by the AIC. Source:

Authors’ calculation.

Robustness check: sigma price convergence

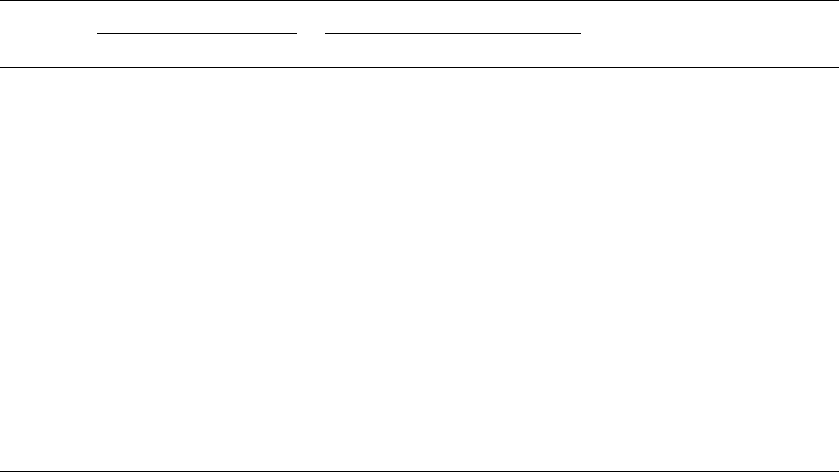

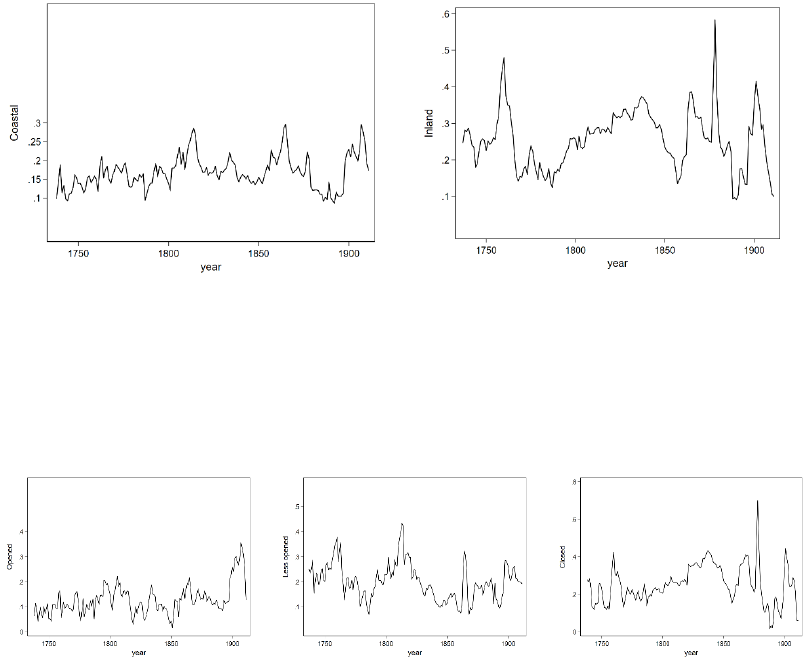

Figure 1 shows the evolution of the grain-price standard deviation between provinces

in the coastal and the inland group for each year. Besides, Figure 2 shows the evolution

in the opened, less-opened, and closed groups. These two figures reveal that the

dispersion in grain prices between Chinese provinces is not characterized by a

downward trend. The econometrics analysis shows that there does not exist a market

integration in late Imperial China, but a fragmentation of markets, which is the legacy

of late Imperial China.

Études et Documents n° 4, CERDI, 2020

17

1(a) Coastal Group

1(b) Inland Group

Figure 1 Sigma Convergence of the Grain Prices in the Geographic Location Groups, 1737‒1911

Source: Authors’ calculation.

2(a) Opened Group

2(b) Less Opened

2(c) Closed Group

Figure 2 Sigma Convergence of the Grain Prices in the Opening Policy Groups, 1737‒1911

Source: Authors’ calculation.

The fragmentation of the China’s territory seems to be an old story, because of several

phenomena: the growing size of the population as previously mentioned, the provincial-

based administrative organization, the technology and may be mainly, the poor level of

transportation infrastructures. Several studies have been devoted to the link between

population and grains. For instance, Chen and Kung (2016) found that like potato in

Europe, maize can be at the origin of population growth during 1776–1910 but unlike

the potato, it had no significant effect on economic growth because of the lack of new

technology. It seems to be the same with grains and the absence of industrial revolution

in China. It did not allowed a better efficiency of the markets, which may explain the

lack of integration. Transportation is another condition to market integration. Most of

Études et Documents n° 4, CERDI, 2020

18

interregional trade relied on natural waterways (Shuie, 2002). Transports were and

stayed during years, one of the most serious problems of the Chinese economy

(Domenach and Richer, 1987). In 1890, manufacturing industries and modern mode of

transport amounted for 0.5 per cent of GDP, and the railways were practically inexistent.

China’s exports amounted 0.6 per cent of GDP, which is low compared with other Asian

countries (Maddison, 2007). It was probably not sufficient to influence the markets

integration. The new trade flows and the new ideas arriving in the opened ports did not

concerned the rest of the country, at least at short term, and it seems that the

improvements in transport were mainly on the sea between them.

4- Conclusion

Since 1978, China gradually opened its market to the rest of the world and became the

major powerhouse of the global economy. China’s economic miracle is greatly due to

the improvement of resource allocation efficiency through domestic and international

market integration. The initiation of China’s market integration, however, should be

revisited in a long-term perspective.

This paper focuses on China’s domestic market integration in the 18th and 19th century.

At that moment, the increased market integration in Western Europe finally triggered

the Industrial Revolution. By contrast, China's domestic markets seemed more isolated

than integrated. It was likely the result of the trade restriction by the Chinese

government. The unequal treaties between the Qing government and western powers,

however, might affect the trade restriction and invigorate market integration.

We thus evaluate domestic market integration in late imperial China. Specifically, the

objective of the paper is to study the consequences of unequal treaties that lift the long-

existing international trade restriction system, on domestic grain markets integration.

Études et Documents n° 4, CERDI, 2020

19

The degree of market integration is assessed by focusing on both long-term co-

movements and sigma convergence in grain prices between provinces. The hypothesis

tested is that of complementarity between international and domestic trade integration:

better access to international markets would promote better functioning of domestic

markets. It appears that the hypothesis according to these treaties would have fostered

a greater integration of domestic markets between provinces is significantly rejected.

We find no evidence for market integration to hold after the 1870s. Our findings are in

line with Cheung’s (2008) argument that the markets in China were only sporadically

integrated in the late imperial era. They are also an illustration of the opposition

between the Mandarins, fixed in the past, turned to the continent, not open to progress,

and the Compradore, interested in changes and turned to the sea, the both of them being

sometimes considered as the “double face of Asia” (Bergère, 1998). The name of

Compradore has been given to some Chinese merchants working with foreigners and

building a little private industrial sector. The treaties have been a shock, and induced a

strong transformation in the ports, but during the Qing dynasty, they probably did not

affected most of the China’s economy and of the China’s people, even though they may

have initiated a process of change for the long-term. So, they did not play as an

integration force for the domestic markets.

Études et Documents n° 4, CERDI, 2020

20

Appendix: Unit Root Tests for the Order of Integration

Before proceeding to the cointegration tests, we need to examine the univariate time

series properties of the data and to confirm that all the price series are non-stationary

and integrated of the same order. To this end, we perform the Augmented Dickey-Fuller

(ADF) test for each time series. All the price series are transformed in a natural

logarithm. Lag lengths are chosen based on the Akaike Information Criteria (AIC).

Our strategy for the unit root tests is as follows. For each province-period-specific series,

we report its ADF test result in natural logarithm level. If the unit-root null is rejected

for the level of the series, then the series is stationary, or I(0). For the non-stationary

series, we then report its ADF test result in logarithm first difference. If the unit-root

null is rejected for the first difference of the series but cannot be rejected for the level,

then we say that the series contains one unit root and is integrated of order one, I(1).

We only perform cointegration tests for the group with at least two I(1) series.

Geographic Location Groups

Table 5 presents the results of the ADF tests in natural logarithm level for the coastal

group. Jiangsu and Shandong (1742‒1806), as well as Fujian, Guangxi, and Zhili

(1871‒1909), show non-stationary grain prices. Other province-period-specific series

are found stationary. Table 6 presents the results of the ADF tests in logarithm first

differences for the non-stationary series. The null hypothesis of non-stationarity can be

rejected for the five prices in first differences.

Études et Documents n° 4, CERDI, 2020

21

Table 5 ADF Tests in Natural Logarithm Levels, Coastal Group

Province name

Study Period

t-Statistic

P-value

Lags

Fujian

1742‒1806

-4.069**

0.011

0

Guangdong

1742‒1806

-4.046**

0.012

1

Guangxi

1742‒1806

-3.967**

0.015

0

Jiangsu

1742‒1806

-2.859

0.183

1

Shandong

1743‒1806

-2.875

0.178

0

Zhejiang

1742‒1806

-5.553***

0.000

3

Zhili

1742‒1806

-4.411***

0.000

0

Fujian

1816‒1860

-4.996***

0.001

2

Guangdong

1816‒1860

-2.149***

0.506

9

Guangxi

1816‒1860

-3.315*

0.077

0

Jiangsu

1816‒1860

-6.167***

0.000

0

Shandong

1818‒1860

-4.015**

0.015

1

Zhejiang

1817‒1860

2.886

0.177

0

Zhili

1821‒1860

-4.386***

0.006

4

Fujian

1871‒1909

-2.622

0.273

0

Guangdong

1871‒1909

-3.577**

0.045

7

Guangxi

1871‒1909

-2.755

0.222

0

Jiangsu

1871‒1909

-3.557**

0.047

1

Shandong

1871‒1909

-3.983**

0.018

3

Zhejiang

1871‒1909

-3.265*

0.087

0

Zhili

1871‒1909

-2.784

0.211

4

Notes: Trend and intercept are included in the test equation of each province. ***Significant at the

1% level. **Significant at the 5% level. *Significant at the 10% level. The lag length is chosen

based on the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC). Source: Authors’ calculation.

Études et Documents n° 4, CERDI, 2020

22

Table 6 ADF Tests in Logarithm First Difference, Coastal Group

Province name

Study Period

t-Statistic

P-value

Lags

Jiangsu

1742‒1806

-6.593***

0.000

3

Shandong

1743‒1806

-16.607***

0.000

1

Fujian

1871‒1909

-6.387***

0.000

0

Guangxi

1871‒1909

-6.832***

0.000

1

Zhili

1871‒1909

-3.960***

0.000

6

Notes: Trend and intercept are included in the test equation of each province. ***Significant at the

1% level. **Significant at the 5% level. *Significant at the 10% level. The lag length is chosen

based on the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC). Source: Authors’ calculation.

Table 7 presents the results of the ADF tests in natural logarithm levels for the inland

group. Although Hunan (1816‒1870) fail to reject the null hypothesis of non-stationary,

the rest series of their group are unlikely to have unit root. Jiangxi and Sichuan (1745‒

1814), in togetherness with Jiangxi, Shanxi, and Sichuan (1871‒1911) cannot reject the

null hypothesis of non-stationary. In Table 8, the null hypothesis of non-stationarity can

be rejected for the five prices in first differences.

Table 7 ADF Tests in Natural Logarithm Levels, Inland Group

Province name

Study Period

t-Statistic

P-value

Lags

Henan

1745‒1814

-4.695***

0.002

1

Hunan

1743‒1814

-3.248*

0.084

0

Jiangxi

1743‒1814

-1.989

0.597

2

Shanxi

1743‒1814

-4.582***

0.002

1

Sichuan

1743‒1814

-1.818

0.686

0

Henan

1818‒1870

-3.278*

0.081

1

Hunan

1816‒1870

-3.010

0.139

0

Jiangxi

1817‒1870

-3.762**

0.027

0

Shanxi

1818‒1870

-3.301*

0.077

1

Sichuan

1816‒1870

-3.318*

0.0740

1

Études et Documents n° 4, CERDI, 2020

23

Henan

1871‒1911

-3.895**

0.021

0

Hunan

1871‒1911

-3.167*

0.105

1

Jiangxi

1871‒1911

-1.854

0.660

0

Shanxi

1871‒1911

-3.182

0.102

3

Sichuan

1871‒1911

-2.582

0.290

0

Notes: Trend and intercept are included in the test equation of each province. ***Significant at the

1% level. **Significant at the 5% level. *Significant at the 10% level. The lag length is chosen

based on the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC). Source: Authors’ calculation.

Table 8 ADF Tests in Logarithm First Difference, Inland Group

Province name

Study Period

t-Statistic

P-value

Lags

Jiangxi

1743‒1814

-69.843***

0.000

1

Sichuan

1743‒1814

-8.608***

0.000

0

Jiangxi

1871‒1911

-6.498***

0.000

0

Shanxi

1871‒1911

-4.459***

0.000

3

Sichuan

1871‒1911

-6.258***

0.000

0

Notes: Trend and intercept are included in the test equation of each province. ***Significant at the

1% level. **Significant at the 5% level. *Significant at the 10% level. The lag length is chosen

based on the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC). Source: Authors’ calculation.

Opening Policy Groups

Table 9 presents the results of the ADF tests in natural logarithm levels for the opened

group. Only Guangdong and Zhejiang (1816‒1860) in a pair cannot reject the null

hypothesis of non-stationary. Table 10 presents the results of the ADF tests in logarithm

first difference the non-stationary series. The null hypothesis of non-stationarity can be

rejected for the two provinces in first differences.

Études et Documents n° 4, CERDI, 2020

24

Table 9 ADF Tests in Natural Logarithm Levels, Opened Group

Province name

Study Period

t-Statistic

P-value

Lags

Fujian

1738‒1806

-4.187***

0.008

0

Guangdong

1738‒1806

-4.216***

0.007

1

Jiangsu

1738‒1806

-3.093

0.116

1

Zhejiang

1738‒1806

-5.633***

0.000

0

Fujian

1816‒1860

-4.996***

0.001

2

Guangdong

1816‒1860

-2.149

0.506

9

Jiangsu

1816‒1860

-6.167***

0.000

0

Zhejiang

1817‒1860

-2.886

0.177

0

Fujian

1871‒1909

-4.760***

0.003

0

Guangdong

1871‒1909

-3.606**

0.041

0

Jiangsu

1871‒1909

-4.013**

0.016

1

Zhejiang

1871‒1909

-3.642**

0.037

0

Notes: Trend and intercept are included in the test equation of each province. ***Significant at the

1% level. **Significant at the 5% level. *Significant at the 10% level. The lag length is chosen

based on the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC). Source: Authors’ calculation.

Table 10 ADF Tests in Logarithm First Difference, Opened Group

Province name

Study Period

t-Statistic

P-value

Lags

Guangdong

1816‒1860

-7.280***

0.000

0

Zhejiang

1817‒1860

-7.466***

0.000

0

Notes: Trend and intercept are included in the test equation of each province. ***Significant at the

1% level. **Significant at the 5% level. *Significant at the 10% level. The lag length is chosen

based on the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC). Source: Authors’ calculation.

Table 11 presents the results of the ADF tests in natural logarithm levels for the less-

opened group. Hubei, Jiangxi, and Sichuan (1871‒1910) in a group cannot reject the

null hypothesis of non-stationary. Table 12 shows that the null hypothesis of non-

stationarity in first differences can be rejected for Jiangxi and Sichuan other than Hubei.

Études et Documents n° 4, CERDI, 2020

25

Table 11 ADF Tests in Natural Logarithm Levels, Less-opened Group

Province name

Study Period

t-Statistic

P-value

Lags

Hubei

1742‒1790

-3.968**

0.016

0

Jiangxi

1742‒1790

-3.578**

0.007

0

Shandong

1742‒1790

-4.973**

0.001

1

Sichuan

1742‒1790

-1.876

0.652

0

Zhili

1742‒1790

-4.587***

0.003

1

Hubei

1805‒1852

-4.273***

0.008

0

Jiangxi

1805‒1852

-3.811**

0.025

0

Shandong

1805‒1852

-3.170

0.104

4

Sichuan

1805‒1852

-3.656**

0.036

0

Zhili

1805‒1852

-3.892**

0.021

1

Hubei

1871‒1910

-2.600

0.282

0

Jiangxi

1871‒1910

-1.923

0.624

0

Shandong

1871‒1910

-3.798**

0.027

3

Sichuan

1871‒1910

-2.533

0.312

0

Zhili

1871‒1910

-3.510*

0.051

0

Notes: Trend and intercept are included in the test equation of each province. ***Significant at the

1% level. **Significant at the 5% level. *Significant at the 10% level. The lag length is chosen

based on the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC). Source: Authors’ calculation.

Table 12 ADF Tests in Logarithm First Difference, Less-opened Group

Province name

Study Period

t-Statistic

P-value

Lags

Hubei

1871‒1910

-2.966

0.156

6

Jiangxi

1871‒1910

-6.139***

0.000

0

Sichuan

1871‒1910

-6.065***

0.000

1

Notes: Trend and intercept are included in the test equation of each province. ***Significant at the

1% level. **Significant at the 5% level. *Significant at the 10% level. The lag length is chosen

based on the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC). Source: Authors’ calculation.

Table 13 presents the results of the ADF tests in natural logarithm levels for the closed

group. Guangxi, Hunan, and Shanxi (1871‒1910) in a group cannot reject the null

Études et Documents n° 4, CERDI, 2020

26

hypothesis of non-stationary. Table 14 shows that the null hypothesis of non-stationarity

can be rejected for all the three prices in first differences.

Table 13 ADF Tests in Natural Logarithm Levels, Closed Group

Province name

Study Period

t-Statistic

P-value

Lags

Guangxi

1743‒1860

-3.914**

0.017

0

Henan

1743‒1860

-4.692**

0.002

1

Hunan

1743‒1860

-3.001

0.140

0

Shanxi

1743‒1860

-4.190***

0.008

1

Guangxi

1816‒1860

-3.314*

0.077

0

Henan

1816‒1860

-3.201*

0.098

1

Hunan

1816‒1860

-3.436*

0.059

1

Shanxi

1816‒1860

-3.338*

0.074

1

Guangxi

1871‒1908

-1.520

0.804

3

Henan

1871‒1908

-3.851**

0.024

0

Hunan

1871‒1908

-1.566

0.788

7

Shanxi

1871‒1908

-3.176

0.105

3

Notes: Trend and intercept are included in the test equation of each province. ***Significant at the

1% level. **Significant at the 5% level. *Significant at the 10% level. The lag length is chosen

based on the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC). Source: Authors’ calculation.

Table 14 ADF Tests in Logarithm First Difference, Closed Group

Province name

Study Period

t-Statistic

P-value

Lags

Guangxi

1871‒1908

-6.848***

0.000

1

Hunan

1871‒1908

-5.225***

0.000

9

Shanxi

1871‒1908

-4.431***

0.006

3

Notes: Trend and intercept are included in the test equation of each province. *** Significant at the

1% level. ** Significant at the 5% level. * Significant at the 10% level. The lag length is chosen

based on the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC). Source: Authors’ calculation.

Études et Documents n° 4, CERDI, 2020

27

Summary

We find that in the 18

th

and early 19

th

century, grain prices in China’s provincial markets

are stationary. Then, in most cases, the search for a common stochastic trend is then

irrelevant: China’s domestic markets were more isolated than integrated. By contrast,

after 1870, grain prices began to show a non-stationary pattern in several coastal

provinces and most of the inland provinces. For the provinces with less or even without

any opened ports, grain prices were in the transition away from stationarity. This

tendency to non-stationarity, however, does not necessarily imply the existence of

common stochastic trends.

Études et Documents n° 4, CERDI, 2020

28

References:

Anderson J.E. and E. van Wincoop (2004), Trade costs, Journal of Economic Literature, 42 (3), 691-

751.

Barett, C.B. and Li, J.R. (2002): Distinguishing between equilibrium and integration in spatial analysis.

American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 84 (2), 292-307.

Bergère, M.Cl. (1998), Le mandarin et le compradore, Hachette Litterature, Paris.

Bernhofen D., M.Eberhardt, J.Li, and S.Morgan (2015), Assessing Market (Dis)Integration in Early

Modern China and Europe, CESifo Working Paper, n°5580, Center for Economic STudies and Ifo

Institute (CESifo), Munich.

Bernhofen D., M.Eberhardt, J.Li, and S.Morgan (2017), The Evolution of Markets in China and

Western EUrope on the Eve of Industrialisation, Research paper series, 2017/12, University of

Nottingham.

Brandt L., D.Ma and T.Rawski (2014), From Divergence to Convergence: Reevaluating the History

Behind China's Economic Boom, Journal of Economic Literature, 52(1), 45-123.

Caron F. (1997). Histoire des chemins de fer en France, Tome 1: 1740-1883, Fayard, Paris.

Chen, S., & Kung, J. K. (2016). Of maize and men: the effect of a New World crop on population and

economic growth in China. Journal of Economic Growth, 21(1), 71-99. doi: 10.1007/s10887-016-

9125-8

Cheung, S. (2008). The Price of Rice: Market Integration in Eighteenth-Century China. Bellingham:

Center for East Asian Studies, Western Washington University.

Domenach J.L. and Ph.Richer, 1987, La Chine, Tome 1, 1949-1971, Points Histoire, Seuil, Paris.

Engle, R. F., & Granger, C. W. J. (1987). Co-Integration and Error Correction: Representation,

Estimation, and Testing. Econometrica, 55(2), 251-276. doi: 10.2307/1913236

Fackler, P. L., & Goodwin, B. K. (2001). Chapter 17 Spatial price analysis Handbook of Agricultural

Economics (1, pp. 971-1024): Elsevier. (Reprinted).

Fairbank JK. and M.Goldman, 2010, Histoire de la Chine, Des origines à nos jours, Tallandier, Paris.

Federico, G. (2012), How much do we know about market integration in Europe? Economic History

Review, 65, 470-497.

Gu, Y. (2013). Essays on Market Integration: The Dynamics and Its Determinants in Late Imperial China,

1736-1911. Degree of Doctor of Philosophy A Thesis submitted to the Hong Kong University of

Science and Technology, Hong Kong University of Science and Technology.

Gu, Y. and J. Kai-Sing Kung, 2019, “Malthus Goes to China: The Effect of Positive Checks on Grain

Market Development, 1736‒1910.” Revise and Resubmit, Journal of Economic History.

Institute, O. E., & Chinese, A. O. S. S. (2010). Grain Prices Data during Daoguang to Xuantong of the

Qing Dynasty. Guilin: Guangxi Normal University Press.

Institute, O. N. A. F., & Chinese, C. F. D. C. (2002). China Food Composition. Beijing: Peking

University Medical Press.

Johansen, S. (1988). Statistical analysis of cointegration vectors. Journal of economic dynamics and

Études et Documents n° 4, CERDI, 2020

29

control, 12(2-3), 231-254

Johansen, S., & Juselius, K. (1990). Maximum likelihood estimation and inference on cointegration—

with applications to the demand for money. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and statistics, 52(2),

169-210

Keller, W., Li, B., & Shiue, C. H. (2011). China’s Foreign Trade: Perspectives From the Past 150

Years. The World Economy, 34(6), 853-892. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9701.2011.01358.x

Li, L. (2000). Integration and Disintegration in North China's Grain Markets, 1738–1911. Journal of

Economic History, 60(3), 665-699

Limao N. and A.J.Venables (2001), Infrastruture, Geographical Disadvantage, transport Costs and Trade,

World Bank Economic Review, 15:3, 451-479.

Maddison A., 2006, La Chine dans l'économie mondiale de 1300 à 2030, Outre-terre, 2, n°15, 89-104.

Maddison A., 2007, Chinese Economic Performance in the Long Run, Second Edition, Revised and

updated: 960-2030 AD.

Marshall A. (1920), Principles in Economics, Macmillan Press, London.

Murphey R., 1977, The Outsiders: The Western Experience in India and China. Ann Arbor, University

of Michigan Press.

Peng, K. (2006). Grain Price since the Qing Dynasty. Shanghai: Shanghai People Press.

Pomeranz K., 2010, Une grande divergence, Albin Michel.

Rawski E., 1972, Agricultural change and the peasant, Cambridge MA, Harvard University Press.

Shiue, C.H. (2002), Transports Costs and Geography of Arbitrage in 18th Century China, American

Economic Review, 92 (5), 1406-1419.

Shiue, C. H., & Keller, W. (2007). Markets in China and Europe on the Eve of the Industrial Revolution.

American Economic Review, 97(4), 1189-1216

Stock J, Watson MW. (1988), . Testing for common trends. Journal of the American Statistical

Association 83 (104), 1097–1107.

Tinbergen J. (1965), International Economic Integration, Elsevier Publishing Company.

Van Dyke, P. A. (2005). The Canton Trade: Life and Enterprise on the China Coast, 1700‒1845. Hong

Kong: Hong Kong University Press.

Wolszczak-Derlacz, J. Price convergence in the EU—an aggregate and disaggregate approach.

International Economics and Economic Policy 5, 25–47 (2008).

Xu, D., & Wu, C. (2000). Chinese Capitalism, 1522‒1840. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK.

Yang, Z. (1996). Statistics and the Relevant Studies on the Historical Population of China. Beijing:

China Reform Publishing House.

Études et Documents n° 4, CERDI, 2020

30