Boswell et al • A Systematic Review of Epidural Steroids 319

Pain Physician Vol. 6, No. 3, 2003

Pain Physician. 2003;6:319-334, ISSN 1533-3159

Epidural Steroids in the Management of Chronic Spinal Pain

and Radiculopathy

A Systematic Review

Mark V. Boswell, MD,PhD*, Hans C. Hansen, MD

#

, Andrea M. Trescot, MD**, and Joshua A. Hirsch, MD

##

From *Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland,

Ohio,

#

The Pain Relief Centers, Conover, North Caro-

lina, **The Pain Center, Orange Park, Florida, and

##

Harvard School of Medicine, Boston, Massachu-

setts. Address Correspondence: Mark V. Boswell,

MD, PhD, 11100 Euclid Avenue, Cleveland, Ohio

44106. E-mail: [email protected]

Funding: No external Support was received in

completion of this study

Epidural injections with or without

steroids are used extensively in the man-

agement of chronic spinal pain. However,

evidence is contradictory with continuing de-

bate about the value of epidural steroid in-

jections in chronic spinal syndromes.

The objective of this systematic re-

view is to determine the effectiveness of epi-

dural injections in the treatment of chronic

spinal pain. Data sources include relevant

literature identied through searchs of MED-

LINE, EMBASE (Jan 1966- Mar 2003), manual

searches of bibliographies of known primary

and review articles, and abstracts from sci-

entic meetings. Both randomized and non-

randomized studies were included in the re-

view based on the criteria established by the

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality

(AHRQ). Studies were excluded from the anal-

ysis if they were simply review or descriptive

and failed to meet minimum criteria.

The results showed that there was

strong evidence to indicate effectiveness of

transforaminal epidural injections in manag-

ing lumbar nerve root pain. Further, evidence

was moderate for caudal epidural injections

in managing lumbar radicular pain. The ev-

idence in management of chronic neck pain,

chronic low back pain, cervical radiculopathy,

spinal stenosis, and post laminectomy syn-

drome was limited or inconclusive.

In conclusion, the evidence of effective-

ness of transforaminal epidural injections in

managing lumbar nerve root pain was strong,

whereas, effectiveness of caudal epidural in-

jections in managing lumbar radiculopathy

was moderate, while there was limited or in-

conclusive evidence of effectiveness of epi-

dural injections in managing chronic spinal

pain without radiculopathy, spinal stenosis,

post lumbar laminectomy syndrome, and cer-

vical radiculopathy.

Keywords: Low back pain, epidural ste-

roids, interlaminar, caudal, transforaminal,

radiculopathy

Lifetime prevalence of spinal pain

has been reported as 65% to 80% in the

neck and low back (1-5). After the initial

episode, modern evidence has shown that

the prevalence of persistent low back and

neck pain ranges from 26% to 75% (6-17).

Patho-anatomic evidence shows that discs

can produce pain in the neck and upper

extremities; thoracic spine, chest wall and

abdominal wall; and low back and lower

extremities. Disc related pain is caused by

disc degeneration, disc herniation, or by

biochemical effects including inflamma-

tion. Human intervertebral disc degen-

eration is a formidable clinical problem

and a leading cause of pain and disability,

resulting in significant healthcare-related

costs (18-22). The degenerative process

in intervertebral discs is associated with

a series of biochemical and morpholog-

ic changes that combine to alter the bio-

mechanical properties of the motion seg-

ment (18, 22-25). Disc degeneration with

or without disc herniation can cause low

back pain (26-30).

Traditionally, compression of nerve

roots or dorsal root ganglion by the her-

niated nucleus pulposus (HNP) has been

regarded as the cause of sciatica, but dur-

ing the past decade, the pivotal role of

multiple etiologies has been implicated.

Thus, proposed etiologies are not lim-

ited to neural compression (22, 26, 27),

but also include vascular compromise (22,

31), inflammation (32-35), biochemical

and neural mechanisms (18, 36-44), in-

ternal disc disruption (45), intraneural

and epidural fibrosis (46-50), dural irrita-

tion (51), spinal stenosis (52), and inflam-

mation and swelling of dorsal root gangli-

on (53-55).

Epidural injection of corticosteroids

is one of the commonly used interven-

tions in managing chronic spinal pain (56-

58). Several approaches are available to ac-

cess the lumbar epidural space: caudal, in-

terlaminar, and transforaminal. Epidural

administration of corticosteroids is one of

the subjects most studied in interventional

pain management with the most systemat-

ic reviews available, though highly contro-

versial (59-71). Bogduk et al (57) in 1994,

after extensive review, concluded that the

balance of the published evidence supports

the therapeutic use of caudal epidurals.

Bogduk (61) in 1999 supported the poten-

tial usefulness of transforaminal steroids

for disc prolapse. Bogduk and Govind

(72) in 1999 concluded that transforami-

nal injection of steroids can be entertained

with the prospect of achieving substantial

and lasting relief of the pain; but if facili-

ties for transforaminal injections are not

available, patients might be offered tempo-

rizing, palliative therapy by means of cau-

dal injection of steroid and local anesthetic

for patients with lumbar radicular pain un-

responsive to lesser, conservative measures,

and for whom surgery might be the only

other option. Bogduk (73) in 1999, in ref-

erence to cervical radicular pain concluded

that in the interest of helping patients avoid

surgery when this is the only other thera-

peutic option being entertained, a cervical

epidural injection of steroids might be of-

fered, or preferably, if facilities are available,

a periradicular injection of steroids might

be offered. However, both of these recom-

mendations (72, 73) apply to acute lumbar

and cervical radicular pain. Bogduk and

McGuirk (74) in reviewing monothera-

py for chronic low back pain (not radicu-

Boswell et al • A Systematic Review of Epidural Steroids320

Pain Physician Vol. 6, No. 3, 2003

Boswell et al • A Systematic Review of Epidural Steroids 321

Pain Physician Vol. 6, No. 3, 2003

lar pain) concluded that epidural steroids

may be indicated for radicular pain, but

they are not indicated for acute back pain

and there is no evidence that they are effec-

tive for chronic low back pain. Koes et al

(62, 63) in a systematic review of random-

ized clinical trials concluded that the effica-

cy of epidural steroid injections has not yet

been established and their benefit, if any,

seems to be of short duration only. van

Tulder et al (65, 75) in 1997 and 2000, con-

cluded that there was conflicting evidence

that epidural steroid injections provide

better short-term pain relief than placebo

for patients with radicular symptoms. Fur-

ther, they concluded that there was mod-

erate evidence that epidural steroid injec-

tions were not effective for chronic low

back pain without radicular symptoms.

Watts and Silagy (64) in a 1995 meta-anal-

ysis, concluded that epidural steroids were

effective based on the definition of effec-

tiveness in terms of pain relief (at least a

75% improvement) in the short-term (60

days) and in the long-term (1 year). Mc-

Quay and Moore (68) in 1998 concluded

that epidural corticosteroid injections were

effective for back pain and sciatica, provid-

ing substantial relief for up to 12 weeks,

but few patients with chronic spinal pain

reported complete relief with majority re-

turning for repeated epidural injections.

Nelemans et al (66) in 2001, in a Cochrane

review of injection therapy, concluded that

epidural steroid injections were not effec-

tive in management of chronic low back or

radicular pain. Vroomen et al (69) in 2000,

in a review of conservative treatment of sci-

atica, concluded that epidural steroids may

be beneficial for subgroups of nerve root

compression. Rozenberg et al (70) in 1999

were unable to determine whether epidural

steroids are effective in common low back

pain and sciatica based on their review. In

contrast, Manchikanti et al (56, 58) in re-

viewing the literature in 2001 and 2003, re-

viewed three types of epidurals separately

rather than in combination as the previous

reviews. They concluded that there was fa-

vorable evidence for caudal epidural ste-

roid injections and transforaminal epidu-

ral steroid injections in managing chronic

low back pain. There are no systematic re-

views available describing pain of cervical

or thoracic origin.

Mechanism of action of epidural in-

jections is not well understood. It is be-

lieved that neural blockade alters or in-

terrupts nociceptive input, reflex mecha-

nisms of the afferent limb, self-sustaining

activity of the neuron pools and neuraxis,

and the pattern of central neuronal activi-

ties (76). Explanations for improvements

are based in part on the pharmacological

and physical actions of local anesthetics,

corticosteroids, and other agents. It is be-

lieved that local anesthetics interrupt the

pain-spasm cycle and reverberating noci-

ceptor transmission, whereas corticoste-

roids reduce inflammation either by in-

hibiting the synthesis or release of a num-

ber of pro-inflammatory substances and

by causing a reversible local anesthetic ef-

fect (77-90), even though an inflamma-

tory basis for either cervical or radicular

pain has not been proven (72, 73).

This systematic review was under-

taken due to conflicting opinions and in-

conclusive evidence in the literature. Fur-

ther, authors strongly believe that due to

the inherent variations and differences

in the 3 techniques applied in delivery of

epidural steroids, previous reviews were

not only incomplete, but also inaccurate.

Thus, due to variations, differences, ad-

vantages, and disadvantages applicable to

each technique (including the effective-

ness and outcomes), caudal epidural in-

jections; interlaminar epidural injections

(cervical, thoracic, and lumbar epidural

injections); and transforaminal epidural

injections (cervical, thoracic, and lumbo-

sacral) are considered as separate entities

within epidural injections and are evalu-

ated as such.

METHODS

Literature Search

Our literature search included MED-

LINE, EMBASE (Jan 1966 – Mar 2003),

systematic reviews, narrative reviews,

cross-references to the reviews and vari-

ous published trials; and peer reviewed ab-

stracts from scientific meetings during the

past two years. The search strategy consist-

ed of diagnostic interventional techniques,

epidural injections and steroids, transfo-

raminal epidurals, nerve root blocks, and

caudal epidural steroids, with emphasis on

chronic pain/low back pain/neck pain/mid

back or thoracic pain or spinal pain.

Selection Criteria

The review focused on randomized

and non-randomized evaluations. The

population of interest was patients suf-

fering with chronic spinal pain for at least

3 months. Three types of epidural injec-

tions with local anesthetic, steroid, or oth-

er drugs, provided for management of

spinal pain were evaluated. All the studies

providing appropriate management with

outcome evaluations of 3 months and sta-

tistical evaluations were reviewed. The

primary outcome measure was pain relief

at various points. The secondary outcome

measures were functional status improve-

ment and complications.

For evaluating the quality of individ-

ual articles, we have used the criteria from

the Agency for Healthcare Research and

Quality (AHRQ) publication (91). This

document described important domains

and elements for randomized and non-

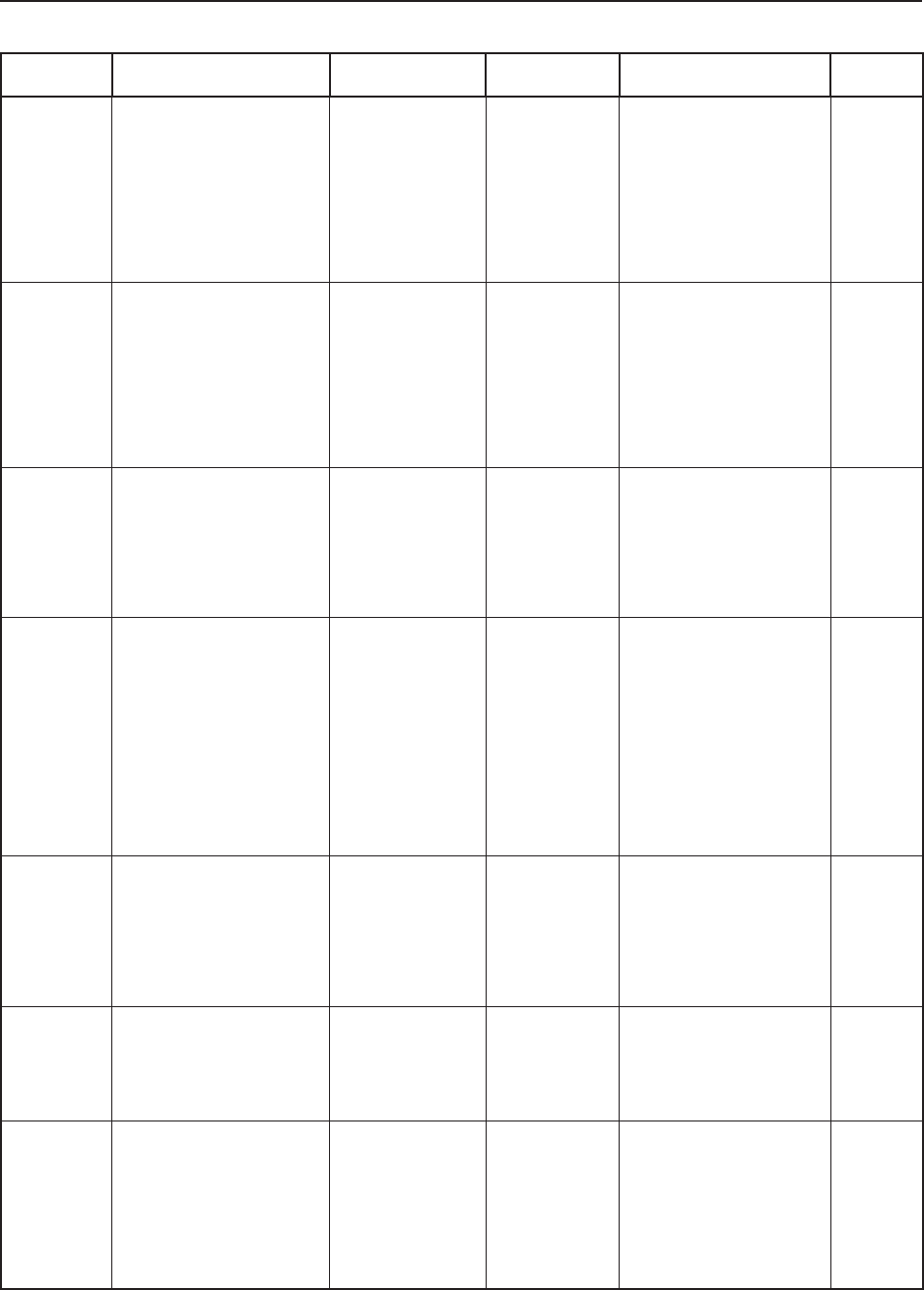

randomized trials as shown in Table 1.

Data Extraction

Study evaluation and inclusion and

exclusion algorithmic approach is shown

in Table 2. Methodologic quality assess-

ment was performed as described in Ta-

ble 1. A score of 4 or more of 7 for ran-

domized trials and a score of 3 or more

Randomized Clinical Trials Observational Studies

1. Study question Study question

2. Study population Study population

3. Randomization Comparability of subjects

4. Blinding

5. Interventions Exposure or intervention

6. Outcomes Outcome measurement

7. Statistical analysis Statistical analysis

8. Results Results

9. Discussion Discussion

10. Funding or sponsorship Funding or sponsorship

Table 1. AHRQ’s important domains and elements for systems to rate quality

of individual articles (91)

* Key domains in italics

Boswell et al • A Systematic Review of Epidural Steroids320

Pain Physician Vol. 6, No. 3, 2003

Boswell et al • A Systematic Review of Epidural Steroids 321

Pain Physician Vol. 6, No. 3, 2003

of 5 was required to meet inclusion crite-

ria. Studies were also eliminated if there

were no appropriate outcomes of at least

3 months or statistical analysis.

Modified quality abstraction forms

described by AHRQ were utilized. All the

potential studies were evaluated by the 3

authors. Any disagreements were resolved

by consensus.

Qualitative Analysis

Qualitative analysis was conduct-

ed, using five levels of evidence for effec-

tiveness of epidural steroids as illustrated

in Table 3. Pain relief was evaluated on

both a short-term (less than 3 months)

and long-term (3 months or longer) ba-

sis. A study was judged to be positive if

the authors concluded that the epidural

steroid injection therapy was more effec-

tive than the reference treatment in ran-

domized trials or simply concluded that it

was effective. All other conclusions were

considered negative. If in the opinion of

reviewers, there was conflict with the con-

clusion, the conclusions were changed

with appropriate explanation.

RESULTS

Caudal Epidural Injections

Multiple reports studying caudal epi-

dural injections included 8 randomized or

double blind trials (92-99), 4 prospective

trials (100-103), and multiple retrospec-

tive evaluations (104-107). The results of

published reports of the randomized tri-

als are described in Table 4, while Table 5

shows description of non-randomized tri-

als (prospective and retrospective).

Of the 8 randomized or double blind

trials, 2 trials were excluded. One study

was excluded (96), due to non-availability

of analyzable information. A second trial

(95) was excluded due to lack of data at 3

months. Of the remaining 6 trials, 4 were

positive for short-term pain relief (92,

93, 97, 98), and 4 were positive for long-

term relief (92, 94, 97, 98). Among the 4

prospective trials (100-103) and 4 retro-

spective trials (104-107) meeting inclu-

sion criteria, all were positive for short-

term and long-term relief with multiple

injections.

Among 6 randomized trials in-

cluded for analyses (92-94, 97-99), only

3 studied predominantly patients with

radiculopathy or sciatica (92-94), 2 stud-

ied post lumbar laminectomy syndrome

(98, 99), and 1 studied mixed population

(97). Of the 3 trials evaluating predomi-

nantly radiculopathy, 2 were positive (92,

93) and one study was negative (94) for

short-term relief, whereas 2 of 3 were pos-

itive for long-term relief (92, 94). Among

two studies with postlumbar laminec-

tomy syndrome (98, 99), only one study

(98) was positive in short-term and long-

term. None of the studies included only

the patients with chronic low back pain.

Among the non-randomized evalua-

tions, including retrospective studies, four

(102-104, 106) of eight (100-107) includ-

ed patients with radicular pain or sciatica,

all showing positive results. Three studies

essentially included patients with chronic

low back pain without demonstrated ra-

dicular pain (100, 101, 105). One study

(107) evaluated the patients with lumbar

canal stenosis.

Interlaminar Epidural Injections

Multiple studies evaluating the ef-

fectiveness of interlaminar epidural in-

jections, specifically the lumbar epidu-

ral injections included 16 randomized

or double blind trials (108-123), 8 non-

randomized prospective trials (124-131),

Table 2. Study evaluation (inclusion/exclusion) algorithm

Study Population

Specific inclusion/exclusion criteria

and

Appropriate diagnostic criteria

No

Yes

No

No

Yes

Yes

Study

Eliminated

Study

Included

Outcomes

Statistical Analysis

Level I -

Conclusive: Research-based evidence with multiple relevant and high-quality

scientic studies or consistent reviews of meta-analyses.

Level II - Strong: Research-based evidence from at least one properly designed randomized,

controlled trial of appropriate size (with at least 60 patients in smallest group); or

research-based evidence from multiple properly designed studies of smaller size; or

at least one randomized trial, supplemented by predominantly positive prospective

and/or retrospective evidence.

Level III – Moderate: Evidence from a well-designed small randomized trial or evidence from

well-designed trials without randomization, or quasi-randomized studies, single

group, pre-post cohort, time series, or matched case-controlled studies or positive

evidence from at least one meta-analysis.

Level IV – Limited: Evidence from well-designed nonexperimental studies from more than one

center or research group

Level V –

Indeterminate: Opinions of respected authorities, based on clinical evidence,

descriptive studies, or reports of expert committees.

Table 3. Designation of levels of evidence

Boswell et al • A Systematic Review of Epidural Steroids322

Pain Physician Vol. 6, No. 3, 2003

Boswell et al • A Systematic Review of Epidural Steroids 323

Pain Physician Vol. 6, No. 3, 2003

Study/Methods Participants Interventions Outcomes Results

Outcomes/

Conclusion

Breivik et al (92)

Randomized

double blind trial.

Randomization

according to a

list of random

numbers.

Parallel, cohort

design

35 patients with

incapacitating

chronic low back pain

and sciatica.

Diagnosis based

on radiculopathy:

arachnoiditis (n=8),

no abnormality

(n=11), inconclusive

ndings (n=5).

Duration: several

months to several

years.

Caudal epidural injection:

Experimental: 20 mL

bupivacaine 0.25% with 80

mg depomethylprednisone

(n=16)

Placebo: 20 mL bupivacaine

0.25% followed by 100 mL

saline (n=19).

Frequency: up to three

injections at weekly intervals.

Timing: not mentioned.

Outcome measures:

1. Pain relief:

signicant diminution of

pain and/or paresis to

a degree that enabled

return to work.

2. Objective

improvement: sensation,

Lasègue’s test, paresis,

spinal reexes, and

sphincter disorders.

56% of the patients

reported considerable

pain relief in experimental

group compared to 26% of

the patients in the placebo

group.

Positive

short-term

and long-

term relief

Bush and Hillier

(93)

Randomized double

blind trial.

28 patients were

randomized; only

23 patients were

entered into the

study.

23 patients with

lumbar nerve root

compromise.

Mean duration

(range) in

experimental group:

5.8 months (1-13

months) and in

control group 4.7

months (1-12).

Caudal epidural injections:

Experimental: 25 mL:

80 mg triamcinolone

acetonide + 0.5% procaine

hydrochloride (n=12)

Control: 25 mL normal saline

(n=11)

Frequency: two caudal

injections, the rst after

admission to the trial and a

second after 2 weeks

Timing: four weeks and

at one year.

Outcome measures:

1. Effect on lifestyle.

2. Back and leg pain

3. Angle of positive SLR.

Signicantly better results

with pain and straight leg

raising in experimental

group in short-term.

Pain not signicantly

different but straight leg

raise signicantly better

for long-term relief.

Positive

short-term

relief and

negative

long-term

relief

Matthews et al (94)

Double blind.

Stratication by

age and gender.

Survival curve

analyses based on

cumulative totals

recovered.

57 patients with

sciatica with a single

root compression

Experimental group:

male/female: 19/4,

median duration of

pain: 4 weeks (range:

8 days-3 months).

Control group:

male/female: 24/10,

median duration of

pain: 4 weeks (range:

3 days-9 weeks).

Caudal epidural injections:

Experimental: 20 mL

bupivacaine 0.125% + 2 mL

(80 mg) methylprednisolone

acetate (n=23).

Control: 2 mL lignocaine

(over the sacral hiatus or into

a tender spot) (n=34)

Frequency: fortnightly

intervals, up to three times

as needed

Timing: 2 weeks, 1, 3, 6,

and 12 months.

Outcome measures:

1. Pain (recovered vs not

recovered).

2. Range of movement

3. Straight leg raising

4. Neurologic

examination

There was no signicant

difference between

experimental and control

group with short-term

relief (67% vs 56%).

After 3 months, patients

in experimental group

reported signicantly more

pain-free than in control

group.

Negative

short-term

relief and

positive

long-term

relief

Helsa and Breivik

(97)

Double blind trial

with crossover

design

69 patients with

incapacitating

chronic low back pain

and sciatica.

36 of 69 previously

been operated on for

herniated disc.

Three caudal epidural

injections of either

bupivacaine with

depomethylprednisolone

80 mg or with bupivacaine

followed by normal saline.

If no improvement had

occurred after 3 injections, a

series of the alternative type

of injection was given.

Timing: not mentioned.

Outcome measures:

signicant improvement

to return to work or to

be retrained for another

occupation

i. 34 of the 58 patients

(59%) receiving caudal

epidural injections

of bupivacaine and

depomethylprednisolone

showed signicant

improvement.

ii. 12 of 49 patients (25%)

who received bupivacaine

followed by saline were

improved.

Positive

short-term

and long-

term relief

Revel et al (98)

Randomized trial.

60 post lumbar

laminectomy patients

with chronic low back

pain

Forceful caudal injection:

Experimental: 125 mg of

prednisolone acetate with

40 mL of normal saline in the

treatment group.

Control: 125 mg of

prednisolone in the control

group.

Timing: 6 months.

Outcome measures: pain

relief.

The proportion of patients

relieved of sciatica was

49% in the forceful

injection group compared

to 19% in the control group

with signicant difference.

Positive

short-term

and long-

term relief

Meadeb et al (99)

Randomized trial.

Parallel-group

study.

47 post lumbar

laminectomy

syndrome patients in

a multicenter study.

Experimental group: forceful

injection of 20 mL of normal

saline with or without 125

mg of epidural prednisolone

acetate.

Control group: 125 mg of

epidural prednisolone.

Frequency: each of the 3

treatments were provided

once a month for 3

consecutive months.

Timing: day 1, day 30

and day 120.

Outcome measures:

visual analog scores.

The VAS scores improved

steadily in the forceful

injection group, producing

a nonsignicant difference

on day 120 as compared to

the baseline (day 30=120

days).

Negative

short-term

and long-

term relief

Table 4. Characteristics of published randomized trials of caudal epidural injections

Boswell et al • A Systematic Review of Epidural Steroids322

Pain Physician Vol. 6, No. 3, 2003

Boswell et al • A Systematic Review of Epidural Steroids 323

Pain Physician Vol. 6, No. 3, 2003

Study/

Methods

Participants Interventions Outcomes Results Outcomes/

Conclusion

Yates (102)

Prospective

evaluation

20 patients with low

back pain and sciatica.

Group I: 60 mg of triamcinolone

(3 mL + 47 mL normal saline)

Group II: 60 mg of triamcinolone

(3 mL + 47 mL lignocaine 0.5%)

Group III: 50 mL saline

Group IV: 50 mL lignocaine

Injections were given at weekly

intervals in a random order

Timing not mentioned.

Subjective and objective

criteria of progress.

Study did not address

pain-relief.

Study focused on

improvement in straight

leg raising which seemed

to correlate with pain-

relief.

Greatest improvement

was noted after the

injection containing

steroid.

The results suggested

that the action of a

successful epidural

injection is primarily

anti-inammatory

and to a lesser extent,

hydrodynamic.

Positive

short-term

and long-

term relief.

Waldman

(103)

Prospective

evaluation

with

independent

observer

review.

53 patients meeting

stringent inclusion

criteria with radicular

pain distribution

anatomically

correlating with

documented disc

herniation and nerve

root impingement.

Treatment: 7.5 mL of 1%

lidocaine and 80 mg of

methylprednisolone with

the rst block and 40 mg of

methylprednisolone with

subsequent blocks.

Subsequent blocks were

repeated in 48 to 72 hour

intervals with the end point

being complete pain relief or 4

caudal epidural blocks.

Timing: 6 weeks, 3

months, 6 months.

Visual analog scale and

verbal analog scores.

Combined visual analog

scale and verbal analog

scores for all patients

were reduced 63% at 6

weeks, 67% at 3 months,

and 71% at 6 months.

Positive

short-term

and long-

term relief.

Manchikanti

et al (100)

A randomized

trial with

convenient

control

group.

70 patients after

failed conservative

management with

physical therapy,

chiropractic and

medication therapy.

All patients were

shown to be negative

for facet joint pain.

Caudal epidural injections:

Group I : no treatment

Group II: local anesthetic and

Sarapin total of 20 mL with 10

mL each.

Group III: 10 mL of local

anesthetic and 6 mg of

betamethasone

Timing: 2 weeks, 1

month, 3 months, 6

months and 1 year.

Outcome measures:

Average pain, physical

health, mental health,

and functional status

Average pain, physical

health, mental health,

functional status, narcotic

intake and employment

improved signicantly

in Group II and Group III

at 2 weeks, 1 month, 3

months, 6 months and

1 year.

Positive

short-term

and long-

term relief.

Manchikanti

et al (101)

Prospective

evaluation in

discogram-

positive and

discogram-

negative

chronic low

back pain

patients.

62 patients were

evaluated.

Negative provocative

discography: 45

patients

Positive provocative

discography: 17

patients

Caudal epidural injections (1-3)

with or without steroids.

Timing: 1 month, 3

months, and 6 months.

Average pain, physical

health, mental health,

functional status,

psychological status,

symptom magnication,

narcotic intake and

employment status.

69% of the patients in

the negative discography

group and 65% of the

patients in the positive

discography group were in

successful category.

Comparison of

overall health status,

psychological status,

narcotic intake and

return to work showed

signicant improvement in

successful category.

Positive

short-term

and long-

term relief.

Hauswirth

and Michot

(104)

Retrospective

evaluation

75 patients with

chronic low back pain

and sciatica

Caudal epidural injections of

local anesthetic and steroids

Timing: not mentioned

Outcome measures: pain

relief

Results were excellent in

60% and good in 24%.

16% of the patients

showed no improvement.

Positive

short-term

and long-

term relief.

Manchikanti

et al (105)

Retrospective

evaluation of

225 patients

with chronic

low back

pain.

Chronic pain

patients who have

failed to respond

to conservative

management with

physical therapy,

chiropractic and

medical therapy.

Group I: Blind lumbar epidural

steroid injections,

Group II: Caudal epidural steroid

injections under uoroscopy.

Group III: Transforaminal

epidural corticosteroid

injections under uoroscopic

visualization.

Duration of pain relief

with each injection.

Outcome measures:

relief ≥ 50%

Cumulative signicant

relief, was reported

following 3 procedures

for a mean of 10.3

+0.96 weeks in patients

receiving caudal

epidurals, in contrast

to 6.7 + 0.37 weeks in

patients receiving blind

lumbar epidural steroid

injections.

Positive

short-term

and long-

term relief.

Table 5. Characteristics and results of non-randomized studies of caudal epidural injections

Boswell et al • A Systematic Review of Epidural Steroids324

Pain Physician Vol. 6, No. 3, 2003

Boswell et al • A Systematic Review of Epidural Steroids 325

Pain Physician Vol. 6, No. 3, 2003

Study/

Methods

Participants Interventions Outcomes Results Outcomes/

Conclusion

Goebert et al

(106)

Retrospective

evaluation of

113 patients.

113 patients at a

tertiary care center

receiving 120

injections. 94 were

caudal epidural

injections

There were no

objective signs present

in the patients.

Epidural injections of 30 mL of

1% procaine combined with 125

mg of hydrocortisone acetate

usually for 3 consecutive or

alternate days.

Timing: 3 months

Pain relief:

Good result 60% relief for

3 months or longer

Failures: 40% to 60%

relief

Poor results: return

of pain in less than 3

months or less than 40%

of relief.

Overall good results in

72% of the patients with

poor results in 17%.

Positive

short-term

and long-

term relief.

Ciocon et al

(107)

Evaluation

of elderly

patients

30 patients with

various degrees of

degenerative lumbar

canal stenosis treated

with caudal epidural

steroid injections.

Mean age: 76 + 6.7 yrs

A total of 3 caudal epidural

steroid injections of 0.5%

lidocaine with 80 mg

of methylprednisolone

administered at weekly intervals

Timing: initial and at 2-

month intervals up to 10

months.

Outcome measures:

the Roland 5-point pain

rating scale.

Pain reduction and

walking capability.

The results showed

signicant pain reduction

for up to 10 months, with

satisfactory relief in 90%

of the patients.

Positive

short-term

and long-

term relief.

Table 5. Characteristics and results of non-randomized studies of caudal epidural injections (Continued)

and multiple other observational trials

(132-161).

Of the 16 studies, 8 studies were ex-

cluded and only 8 met inclusion crite-

ria. One study (112) was excluded as they

studied effects of subarachnoid and epi-

dural midazolam. Two studies (118, 119)

studied diabetic polyneuropathy and in-

tractable post herpetic neuralgia. One

study (123) evaluated only inpatients,

whereas 3 evaluations (113, 114, 120)

failed to evaluate long-term relief, and

finally, one study (121) was not includ-

ed due to lack of data for review. Table

6 illustrates various characteristics and re-

sults of published randomized or double

blind trials meeting inclusion criteria. Of

the 8 non-randomized prospective trials,

only 3 trials (124-126) met criteria for in-

clusion, whereas the remaining 5 studies

(127-131) were eliminated due to multi-

ple issues.

Of the 8 randomized trials included

in evaluation, 6 were positive for short-

term relief (108, 111, 115-117, 122),

whereas only 3 were positive for long-

term relief (111, 117, 122). Numerous

non-randomized trials, both prospective

and retrospective, reported good results

in 18% to 90% of patients receiving cer-

vical or lumbar interlaminar epidural ste-

roid injections, however, without specific

follow-up period. Among the 3 prospec-

tive trials included for evaluation (124-

126), only one was positive (125), one was

indeterminate (124), and one was nega-

tive (126).

Of the 2 randomized trials, which

were positive, Dilke et al (111) studied low

back pain and sciatica, whereas Cataneg-

ra (117) studied chronic cervical radicu-

lar pain. Cuckler et al (110) also included

post lumbar laminectomy syndrome pa-

tients with overall negative results. Due

to a multitude of randomized trials and

availability of double blind or random-

ized, and non-randomized prospective

trials in managing lumbar radicular pain,

evidence from retrospective trials was not

included. However, due to only one ran-

domized trial (117) and one prospective

study (122), in managing cervical radicu-

lar pain, multiple retrospective trials (132-

144) were included for review. Retrospec-

tive reports were also considered in man-

aging chronic low back pain with or with-

out radiculopathy (145-161).

Some studies evaluated the effec-

tiveness of cervical epidural steroid in-

jections in patients not only with cervi-

cal radicular pain, but also other cervical

pain problems (134, 137, 140, 142). One

study (138) studied patients with cervi-

cal radiculopathy. All these retrospective

studies show that there is probable bene-

fit in a significant number of patients in

short-term, however the benefits appear

to be limited in long-term. The results

for chronic low back pain also showed

positive results in short-term and nega-

tive results in long-term in chronic low

back pain.

Transforaminal Epidural Injections

Multiple reports evaluating the effec-

tiveness of transforaminal epidural injec-

tions included 7 randomized trials (120,

162-167); 8 prospective evaluations (124,

168-174); one prospective evaluation of

change in size and pattern of disc hernia-

tion (175); and multiple retrospective re-

ports (105, 176-187).

Among the 7 randomized controlled

trials, only 3 trials (120, 162, 164) met cri-

teria for inclusion. The trial by Kolsi et

al (166) was not included since the mea-

surements were only of short-term dura-

tion. Devulder et al (165) evaluated the

effectiveness of transforaminal epidurals

in post laminectomy syndrome. Karp-

pinen et al (163, 164) used two publi-

cations to report the results of one tri-

al. Buttermann (167) presented prelimi-

nary results at a scientific meeting in 1999

without subsequent publication. Details

of the randomized trials examining the

effectiveness of transforaminal epidural

steroid injections in the management of

spinal pain are illustrated in Table 7. All

3 studies showed effectiveness of trans-

foraminal epidural steroids in managing

nerve root pain. One study (164) showed

ineffectiveness of transforaminal epidur-

als for disc extrusions.

Among the prospective evaluations,

3 investigations, those of Vad et al (169),

Lutz et al (168), and Bush and Hilli-

er (124) met inclusion criteria. Others

were excluded because some were per-

formed under CT, long-term results were

not evaluated in some, and in others, mul-

tiple injections were performed in a short

period of time. As shown in Table 8, all

3 prospective trials (124, 168, 169) were

positive for short-term and long-term

relief. Among the retrospective evalu-

ations, 4 studies by Weiner and Fraser

Boswell et al • A Systematic Review of Epidural Steroids324

Pain Physician Vol. 6, No. 3, 2003

Boswell et al • A Systematic Review of Epidural Steroids 325

Pain Physician Vol. 6, No. 3, 2003

Study/

Methods

Participants Interventions Outcomes Results Outcomes/

Conclusion

Carette et al

(108)

Randomized

double blind

trial

158 patients with sciatica due to

a herniated nucleus pulposus.

78 patients in the treatment

group.

80 patients in the placebo

group.

50% of the patients had L4/5

disc herniation and 46% of

the patients had L5/S1 disc

herniation.

Experimental group:

methylprednisolone

acetate (80 mg and 8

mL of isotonic saline)

Control group: isotonic

saline 1 mL

Frequency: 3 epidural

injections 3 weeks

apart

Timing: 6 weeks, 3

months, 12 months

Outcome

measures:

Need for surgery

Oswestry Disability

scores

After 6 weeks, a signicant

difference was seen with

improvement in leg pain in the

methylprednisolone group.

After 3 months, there were no

signicant differences between

groups.

At 12 months, the cumulative

probability of back surgery was

equal in both groups.

Positive

short-term

Negative

long-term

relief

Snoek et al

(109)

Randomized

trial

51 patients with lumbar root

compression documented

by neurological decit and a

concordant abnormality noted

on myelography.

27 patients in experimental

group

24 patients in control group

Experimental

group: 80 mg of

methylprednisolone

(2 mL)

Control group: 2 mL of

normal saline

Frequency: single

injection

Timing: 3 days and

an average of 14

months

Outcome

measures:

Pain, sciatic nerve

stretch tolerance,

subjective

improvement,

surgical treatment.

No statistically signicant

differences were noted in

either group with regards to

low back pain, sciatic nerve

stretch tolerance, subjective

improvement, and surgical

treatment.

Negative

short-term

and long-

term relief

Cuckler et al

(110)

Randomized

double blind

trial

73 patients with back pain

due to either acute herniated

nucleus pulposus or spinal

stenosis.

Duration: greater than 6 months.

Experimental group = 42

patients, control group = 31

patients

Experimental group:

80 mg (2 mL) of

methylprednisolone +

5 mL of procaine 1%

Control group: 2

mL saline + 5 mL of

procaine 1%

Timing: 24 hours

and an average of

20 months

Outcome

measures:

subjective

improvement.

Need for surgery.

There was no signicant short-

term or long-term improvement

among both groups.

Negative

short-term

and long-

term relief

Dilke et al (111)

Randomized

trial

100 patients with low back pain

and sciatica of 1 week to more

than 2 yrs.

51 patients in experimental

group

48 patients in control group

Experimental

group: 10 mL of

saline + 80 mg of

methylprednisolone

Control group: 1 mL of

saline

Frequency: up to 2

injections separated

by 1 week

All patients received

physical therapy with

hydrotherapy and

exercise

Timing: 2 weeks

and 3 months

Outcome

measures: time of

bedrest, days of

hospitalization,

pain relief,

consumption of

analgesics and

resumption of

work 3 months

later

60% of the patients in the

treatment group and 31% of the

patients in the control group

improved immediately after the

injections.

A greater proportion of actively

treated patients had no pain at

3 months, took no analgesics,

resumed work and fewer of

them underwent subsequent

surgery or other non-surgical

treatment.

Positive

short-term

and long-

term relief

Ridley et al

(115)

Randomized

trial

35 patients with low back pain

and sciatica of mean duration

approximately 8 months

19 patients in experimental

group

16 patients in control group

Experimental

group: 10 mL of

saline + 80 mg of

methylprednisolone

(n=19)

Control group: saline

2 mL, interspinous

ligament (n=16)

Timing: 1 weeks, 2

weeks, 3 months

and 6 months

Outcome

measures:

pain control

improvement in

straight leg raising

90% of the patients in the

treated group compared to 19%

in the control group showed

improvement at 1 week, 2

weeks and 12 weeks.

By 24 weeks, the relief

deteriorated to pre-treatment

levels

Positive

short-term

relief

Negative

long-term

relief

Rogers et al

(116)

Randomized

single blind

sequential

analysis

30 patients with low back pain

15 patients in experimental

group

15 patients in control group

Experimental group:

local anesthetic +

steroid

Control group: local

anesthetic alone

Timing: 1 month

Outcome

measures: pain

relief

Nerve root tension

signs

Lumbar epidural injection

of steroid together with

local anesthetic produced

signicantly better results.

Long-term results were similar

for both.

Positive

short-term

relief

Negative

long-term

relief

Catanegra et al

(117)

Randomized

trial with

cervical

interlaminar

epidural

steroid

injections

24 patients with chronic cervical

radicular pain, however without

need of surgery, but suffering for

more than 12 months

i. 14 patients receiving local

anesthetic and steroid

ii. 10 patients receiving local

anesthetic, steroid + morphine

sulfate

i. 0.5% lidocaine

+ triamcinolone

acetonide

ii. Local anesthetic

+ steroid + 2.5 mg of

morphine sulfate

Timing: 1 month,

3 months, and 12

months

Outcome

measures: pain

relief

The success rate was 79% vs.

80% in group I and II.

Overall, initial success rate was

96%, 75% at 1 month, 79% at

3 months, 6 months, and 12

months.

Positive

short-term

and long-

term relief

Table 6. Characteristics of published randomized trials of interlaminar epidural injections

Boswell et al • A Systematic Review of Epidural Steroids326

Pain Physician Vol. 6, No. 3, 2003

Boswell et al • A Systematic Review of Epidural Steroids 327

Pain Physician Vol. 6, No. 3, 2003

Study/

Methods

Participants Interventions Outcomes Results Outcomes/

Conclusion

Stav et al (122)

Randomized

trial of cervical

epidural

steroid

injections

52 patients with chronic,

resistant cervical brachialgia

25 patients in experimental

group

17 patients in control group

Experimental group:

cervical epidural

steroid and lidocaine

injections

Control group:

steroid and lidocaine

injections into the

posterior neck

muscles

Frequency: 1 to 3

injections were

administered at 2

weeks intervals,

based on the clinical

response

All patients continued

pre-study treatment

with drugs and

physiotherapy

Timing: 1 week and

1 year

Outcome

measures: pain

relief, change

in deep tendon

reexes or sensory

loss, change in

range of motion

Reduction of daily

dose of analgesics

Return to work

After 1 week, 76% of the

patients in cervical epidural

group compared to 36% of the

patients in the neck injection

group showed improvement.

At 1 year, 68% of the cervical

epidural group continued to

have relief compared to 12% of

the control group.

Positive

short-term

and long-

term relief

Table 6. Characteristics of published randomized trials of interlaminar epidural injections (Continued)

Study/

Methods

Participants Interventions Outcomes Results Outcomes

/Conclusion

Riew et al (162)

Randomized

double blind

trial

55 patients with lumbar

disc herniations or spinal

stenosis referred for surgical

evaluation.

All subjects had clinical

indications for surgery, and

radiographic conrmation of

nerve root compression.

All patients had failed a

minimum of 6 weeks of

conservative care or had

unrelenting pain.

28 patients in experimental

group (71%)

27 patients in control group

(33%)

Experimental group:

transforaminal nerve root or

epidural steroid injection with

1 mL of 0.25% bupivacaine

and 6 mg of betamethasone

Control group: 1 mL of 0.25%

bupivacaine.

The patient was allowed to

choose to receive as many as

4 injections at any time during

the follow-up.

Timing: 1 year

Outcome measures:

Injections were

considered to have

failed if the patient

opted for operative

treatment.

Multiple injection

therapy was not

considered as

failure.

North American

Spine Society

questionnaire.

Of the 28 patients

in the experimental

group with

bupivacaine and

betamethasone, 20

decided not to have

the operation.

Of the 27 patients

in the control group

receiving bupivacaine

alone, 9 elected

not to have the

operation. They had

highly signicant pain

relief and functional

improvement.

Positive

short-term

and long-term

relief.

Kraemer et al

(120)

Randomized

double blind

study

49 patients with lumbar

radicular symptoms with 24

patients in the steroid group

and 25 patients in the normal

saline group.

Experimental group:

transforaminal epidural with

local anesthetic and 10 mg of

triamcinolone.

Control group: local

anesthetic only.

Normal saline group received

IM steroid injections to avoid

the systemic steroid effect.

Timing: not

mentioned

Outcome measures:

Pain relief

Single-short epidural

perineural injection

was effective it the

treatment of lumbar

radicular pain.

Positive

short-term

and long-term

relief.

Karppinen et al

(163, 164)

Randomized

double blind

trial

160 consecutive, eligible

patients with sciatica with

unilateral symptoms of 1 to 6

months duration.

None of the patients have

undergone surgery.

Experimental group:

local anesthetic and

methylprednisolone

Control group:

normal saline

Timing: 2 weeks, 3

months, 6 months

Outcome measures:

Pain relief, sick

leaves, medical

costs, and future

surgery

Nottingham Health

Prole

In the case of

contained herniations,

the steroid injection

produced signicant

treatment effects

and short-term in

leg pain, straight leg

raising, disability and

in Nottingham Health

Prole, emotional

reactions and cost

effectiveness.

Positive

short-term

and long-term

relief.

Table 7. Details of randomized trials studying the effectiveness of transforaminal epidural steroid injections for

low back pain

Boswell et al • A Systematic Review of Epidural Steroids326

Pain Physician Vol. 6, No. 3, 2003

Boswell et al • A Systematic Review of Epidural Steroids 327

Pain Physician Vol. 6, No. 3, 2003

Study/Methods Participants Interventions Outcomes Results Outcomes/

Conclusion

Vad et al (169)

A prospective

study randomized

by patient choice

from the private

practice of a single

physician.

Patients with leg pain, old-

er than 18 years, had been

symptomatic longer than

6 weeks, had undergone

a lumbar spine magnetic

resonance imaging scan

documenting herniated

nucleus pulposus or mani-

fested clinical signs such

as radicular pain and sen-

sory or xed motor de-

cits consistent with lum-

bar radiculopathy.

Experimental group: transforam-

inal epidural steroid injection.

1.5 mL each of betamethasone

acetate, 9 mg and 2% preserva-

tive-free Xylocaine per level.

Control group: trigger point in-

jections.

All patients received a self-di-

rected home lumbar stabiliza-

tion program consisting of four

simple exercises emphasizing

hip and hamstring exibility and

abdominal and lumbar paraspi-

nal strengthening.

Timing: 3 weeks, 6

weeks, 3 months,

6 months, and 12

months.

Outcome mea-

sures:

Roland-Morris

score, visual nu-

meric score, nger-

to-oor distance,

patient satisfaction

score.

Fluoroscopically guided

transforaminal epidural

steroid injections yielded

better results compared

to saline trigger point in-

jections.

The group receiving trans-

foraminal epidural steroid

injections had a success

rate of 84%, as compared

with the 48% for the group

receiving trigger point in-

jections.

Positive

short-term

and long-

term relief

Lutz et al (168)

A prospective case

series.

69 patients with lumbar

herniated nucleus pulpo-

sus and radiculopathy. 69

patients were recruited.

Every patient in the case

series had documented

magnetic resonance imag-

ing ndings that showed

disc herniation with nerve

root compression.

Transforaminal epidural steroid

injections with 1.5 cc of 2% Xy-

locaine and 9 mg of betametha-

sone acetate.

Timing: 28 to 144

weeks

Outcome mea-

sures: At least

±50% reduction in

pre-injection and

post-injection visu-

al numerical pain

scores.

A successful outcome

was reported by 52 of the

69 patients (75.4%) at

an average follow-up of

80 weeks (range 28-144

weeks).

Positive

short-term

and long-

term relief

Bush and Hillier

(124)

Prospective evalu-

ation of cervical

interlaminar and

transforaminal

epidural injections

68 patients with neck

pain and cervical

radiculopathy.

Following the rst blind cervical

epidural injection, if a signicant

improvement was not seen, a

repeat injection was performed

trans foraminally with uorosco-

py guidance within 1 month.

A third injection was also per-

formed if needed in the same

manner as the second injection.

Timing: 1 month to

1 year

Outcome mea-

sures: Pain relief

93% of the patients were

reported to have good pain

relief lasting for 7 months.

Positive

short-term

and long-

term relief

Weiner and Fraser

(183)

A retrospective

evaluation

30 patients with lateral

foraminal or extraforami-

nal herniation of a lumbar

disc were evaluated with

foraminal injection of local

anesthetic and steroids

for radiculopathy

Transforaminal injection of 2 mL

of 1% lidocaine combined with

11.4 mg of injectable betameth-

asone.

Timing: 1 to 10

years

Outcome mea-

sures:

Pain scale:

Use of analgesics,

work status, recre-

ational activities.

22 had lasting relief of

their symptoms.

14 had no pain allowing

them to participate freely

in their usual activities.

Of the 17 patients at work,

13 had returned to the

same job.

Positive

short-term

and long-

term relief

Manchikanti et al

(105)

Compared the 3

routes of epidural

steroid injections

in the manage-

ment of low back

in retrospective

manner

225 patients randomly de-

rived from a total sample

of 624 patients suffering

with low back pain from

a total of 972 patients re-

ferred for pain manage-

ment were evaluated.

Group I: interlaminar epidurals

with a midline approach without

uoroscopy.

Group II: caudal epidurals un-

der uoroscopy.

Group III: transforaminal epidu-

ral steroid injections.

Timing: 1, 3, 6, 12

months

Outcome mea-

sures: Pain relief

Group III reported +50%

relief per procedure of

7.69 + 1.20 weeks, which

was superior to blind inter-

laminar epidurals.

Positive

short-term

and long-

term relief

Rosenberg et al

(186)

Retrospective

evaluation

92 patients with radicu-

lopathic back pain due

to spinal stenosis, herni-

ated discs, spondylolis-

thesis, and degenerative

discs.

Group I: Previous back surgery

(16%)

Group II: Discogenic abnormali-

ties: herniations, bulges or de-

generation (42%)

Group III: spinal stenosis (32%)

Group IV: those without MRI

(11%)

Timing: 2, 6 and

12 months

Outcome mea-

sures:

Pain relief

The pain scores for all pa-

tients improved signi-

cantly at all three points.

Greater than 50% im-

provement after one year

was seen in 23% of Group

I; 59% in Group II; 35%

in Group III and 67% in

Group IV.

Positive

short-term

and long-

term relief

Wang et al (187)

Retrospective

evaluation

69 patients with lumbar

herniated discs

All patients were treated with 1-

6 epidural steroid injections

Timing: NA

Outcome mea-

sures: Pain relief

Avoidance of sur-

geon

77% of patients had sig-

nicant improvement and

refused surgery

Positive

short-term

and long-

term relief

Table 8. Details and results of non-randomized trials of transforaminal epidural injections

Boswell et al • A Systematic Review of Epidural Steroids328

Pain Physician Vol. 6, No. 3, 2003

Boswell et al • A Systematic Review of Epidural Steroids 329

Pain Physician Vol. 6, No. 3, 2003

(183), Rosenberg et al (186), Wang et al

(187) and Manchikanti et al (105) met

inclusion criteria. All retrospective eval-

uations showed positive short-term and

long-term relief.

Complications and Side Effects

The most common and worrisome

complications and side effects of caudal,

interlaminar, and transforaminal epidur-

al injections are of two types: those relat-

ed to the needle placement and those re-

lated to drug administration. Complica-

tions include dural puncture, spinal cord

trauma, infection, hematoma formation,

abscess formation, subdural injection, in-

tracranial injection, epidural lipomatosis,

pneumothorax, nerve damage, headache,

death, brain damage, increased intra-

cranial pressure, intravascular injection,

vascular injury, cerebral vascular or pul-

monary embolus, and effects of steroids

(188-239). No major complications or

side effects were reported in the trials pre-

sented in the review.

DISCUSSION

This systematic review evaluated the

effectiveness of epidural injections in pa-

tients with chronic spinal pain. The evi-

dence was evaluated for 3 types of epidu-

rals separately.

For the transforaminal epidural in-

jections, three (120, 162, 164) of the 7

randomized trials (120, 162-167), showed

positive short-term and long-term ef-

fectiveness for lumbar nerve root pain.

Three prospective evaluations (124, 168,

169) showed positive short and long-term

results. Four retrospective evaluations

(105, 183, 186, 187) were included which

showed positive results overall. Multiple

randomized and non-randomized tri-

als of transforaminal epidural injections

provided strong evidence for short-term

and long-term relief in managing lum-

bar nerve root pain. Their effectiveness

in post lumbar laminectomy syndrome

and disc extrusions is inconclusive. There

is no published evidence of effectiveness

of transforaminal epidural injections in

chronic neck or chronic low back pain,

post cervical or laminectomy syndrome,

and cervical or thoracic radicular pain.

The combined overall evidence of

caudal epidural steroid injections, based

on randomized trials and nonrandomized

trials (prospective and retrospective trials)

is strong for short-term relief and moder-

ate for long-term relief with two (92, 93)

of three (92-94) randomized trials, and

4 of 4 non-randomized trials (102-104-

106) demonstrating positive results in ra-

dicular pain. However, the evidence for

chronic low back pain and spinal stenosis

appears to be limited as there are no ran-

domized or double-blind trials evaluating

this effect. Non-randomized trials (100,

101, 105, 107) all showed positive results

in chronic low back pain after the facet

joint pain was excluded (100, 101, 105),

and also in spinal stenosis (107).

For interlaminar epidural injections,

of the 8 randomized trials included, 6 tri-

als (108, 111, 115-117, 122) showed posi-

tive evidence for short-term relief, and 3

of 8 (111, 117, 122) showed positive evi-

dence for long-term relief. The overall ef-

fectiveness of interlaminar epidural ste-

roid injections in managing chronic spi-

nal pain is moderate for short-term relief

and limited for long-term relief in man-

aging lumbar radicular pain. However,

there was no significant evidence based

on randomized trials of effectiveness of

interlaminar epidural steroids in manag-

ing cervical radicular pain. Further anal-

ysis combining one randomized trial, one

prospective trial and multiple retrospec-

tive evaluations (132-144), demonstrat-

ed moderate evidence for short-term,

and limited evidence for long-term re-

lief. The limited evidence for manage-

ment of chronic low back pain without

radiculopathy was based on all the retro-

spective studies.

The first systematic review of effec-

tiveness of epidural steroid injections was

performed by Kepes and Duncalf in 1985

(59). They concluded that the rationale

for epidural and systemic steroids was not

proven. However, in 1986 Benzon (60),

utilizing the same studies, concluded that

mechanical causes of low back pain, es-

pecially those accompanied by signs of

nerve root irritation, may respond to epi-

dural steroid injections. The difference in

the conclusion of Kepes and Duncalf (59)

and Benzon (60) may have been due to the

fact that Kepes and Duncalf (59) included

studies on systemic steroids whereas Ben-

zon (60) limited his analysis to studies on

epidural steroid injections only.

The debate concerning epidural ste-

roid injections is also illustrated by the

recommendations of the Australian Na-

tional Health and Medical Research

Council Advisory Committee on epidur-

al steroid injections (57). In this report,

Bogduk et al (57) extensively studied cau-

dal, interlaminar, and transforaminal epi-

dural injections, including all the litera-

ture available at the time, and concluded

that the balance of the published evidence

supports the therapeutic use of caudal

epidurals. They also concluded that the

results of lumbar interlaminar epidural

steroids strongly refute the utility of epi-

dural steroids in acute sciatica. Bogduk

(61) updated his recommendations in

1999, recommending against epidural ste-

roids by the lumbar route because effec-

tive treatment required too high a number

for successful treatment, but supporting

the potential usefulness of transforami-

nal steroids for disc prolapse. In 1995,

Koes et al (62) reviewed 12 trials of lum-

bar and caudal epidural steroid injections

and reported positive results from only six

studies. However, review of their analysis

showed that there were 5 studies for cau-

dal epidural steroid injections and 7 stud-

ies for lumbar epidural steroid injections.

Four of the five studies involving caudal

epidural steroid injections were positive,

whereas 5 of 7 studies were negative for

lumbar epidural steroid injections. Koes

et al (63) updated their review of epidu-

ral steroid injections for low back pain

and sciatica, including three more stud-

ies with a total of 15 trials which met the

inclusion criteria. In this study, they con-

cluded that of the 15 trials, eight reported

positive results of epidural steroid injec-

tions. Both reviews mostly reflected the

quality of studies, rather than any mean-

ingful conclusion.

Nelemans et al’s (66) Cochrane re-

view of injection therapy for subacute

and chronic benign low back pain includ-

ed 21 randomized trials. Of these, 9 were

of epidural steroids. They failed to sepa-

rate caudal from interlaminar epidural

injections, but still concluded that con-

vincing evidence is lacking regarding the

effects of injection therapy on low back

pain. Rozenberg et al (70), in a systematic

review, identified 13 trials of epidural ste-

roid therapy. They concluded that 5 tri-

als demonstrated greater pain relief with-

in the first month in the steroid group as

compared to the control group. Eight tri-

als found no measurable benefits. They

noticed many obstacles for meaningful

comparison of cross studies, which in-

cluded differences in the patient popula-

tions, steroid used, volume injected, and

number of injections. These authors

were unable to determine whether epidu-

ral steroids are effective in common low

Boswell et al • A Systematic Review of Epidural Steroids328

Pain Physician Vol. 6, No. 3, 2003

Boswell et al • A Systematic Review of Epidural Steroids 329

Pain Physician Vol. 6, No. 3, 2003

back pain and sciatica based on their re-

view. Rozenburg et al (70) concluded that

3 of the top 5 rated studies did not dem-

onstrate significant benefit of the steroid

over the non-steroid group. Hopayiank

and Mugford (71) expressed frustration

over the conflicting conclusions from two

systematic reviews of epidural steroid in-

jections for sciatica and asked which evi-

dence should general practitioners heed?

Multiple previous reviews have criticized

the studies evaluating the effectiveness

of epidural injections. Criticisms ranged

from methodology, small size of the study

populations, and other limitations, in-

cluding long-term follow-up and out-

come parameters. Many of these deficien-

cies were noted in our review also, in spite

of the fact that we have included non-ran-

domized trials.

With respect to complications and

side effects, only transient minor com-

plaints were reported in the trials present-

ed in this review. However, potential com-

plications also have been described. Spi-

nal cord trauma and spinal cord or epidu-

ral hematoma formation are catastroph-

ic complications. One of the suggestions

has been to perform interventional proce-

dures only in an awake patient and in the

cervical spine by limiting the midline in-

jection to be performed only at C7/T1 ex-

cept in rare circumstances. However, it

has also been reported that even an awake

patient may not be able to detect spinal

cord puncture (241). Thus, the recom-

mendation to limit the midline injection

only at C7/T1 is based neither on con-

sistent clinical nor anatomical evidence.

Three cases of paraplegia were reported

after lumbosacral nerve root block in post

lumbar laminectomy patients (229). In

each patient, paraplegia was reported sud-

denly. In each patient after injection of a

steroid solution, post procedure magnet-

ic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed spi-

nal cord edema in the low thoracic region.

The authors postulated that in these pa-

tients, the spinal needle penetrated or in-

jured an abnormally low dominant radic-

ulomedullary artery, a recognized ana-

tomical variant. This vessel, also known

as artery of Adamkiewicz, in 85% of indi-

viduals arises between T9 and L2, usually

from the left, but in a minority of people,

may arise from the lower lumbar spine

and rarely even from as low as S1 (229).

Others also have reported similar compli-

cations (234-236). Side effects related to

the administration of steroids are gener-

ally attributed either to the chemistry or

to the pharmacology of the steroids. The

major theoretical complications of corti-

costeroid administration include suppres-

sion of pituitary-adrenal access, hyper-

corticism, Cushing’s syndrome, osteopo-

rosis, avascular necrosis of bone, steroid

myopathy, epidural lipomatosis, weight

gain, fluid retention, and hyperglycemia.

One study (228) showed no significant

difference in patients undergoing various

types of interventional techniques with or

without steroids. Further, it has also been

shown that the most commonly used ste-

roids in the epidural steroids in the Unit-

ed States, methylprednisolone acetate, tri-

amcinolone acetonide, and betametha-

sone acetate, and phosphate mixture have

all been shown to be safe at epidural ther-

apeutic doses in both clinical and experi-

mental studies (242-250).

CONCLUSION

This systematic review, which includ-

ed not only randomized trials, but also all

available non-randomized trials, showed

variable effectiveness of epidural injections.

Strong evidence was provided for transfo-

raminal epidural steroid injections in man-

aging lumbar nerve root pain. Moderate

evidence was provided for caudal epidural

steroid injections in managing lumbar ra-

dicular pain. Evidence for other conditions

was either limited or inconclusive.

REFERENCES

1. Hellsing A, Bryngelsson I. Predictors of

musculoskeletal pain in men. A twenty-

year follow-up from examination at enlist-

ment. Spine 2000; 25:3080-3086.

2. Lawrence RC, Helmick CG, Arnett FC. Es-

timates of the prevalence of arthritis and

selected musculoskeletal disorders in the

United States. Arthritis Rheum 1998; 41:

778-799.

3. Bressler HB, Keyes WJ, Rochon PA et al.

The prevalence of low back pain in the el-

derly. A systemic review of the literature.

Spine 1999; 24:1813-1819.

4. Cassidy D, Carroll L, Cotê P: The Saskatch-

ewan Health and Back Pain Survey. The

prevalence of low back pain and related

disability in Saskatchewan Adults. Spine

1998; 23:1860-1867.

5. Côté DC, Cassidy JD, Carroll L. The Sas-

katchewan Health and Back Pain Survey.

The prevalence of neck pain and related

disability in Saskatchewan adults. Spine

1998; 23:1689-1698.

6. Elliott AM, Smith BH, Hannaford PC et al.

The course of chronic pain in the commu-

nity: Results of a 4-year follow-up study.

Pain 2002; 99:299-307.

7. van den Hoogen HJ, Koes BW, Deville W et

al. The prognosis of low back pain in gen-

eral practice. Spine 1997; 22:1515-1521.

8. Croft PR, Papageorgiou AC, Thomas E et

al. Short-term physical risk factors for

new episodes of low back pain. Prospec-

tive evidence from the South Manchester

Back Pain Study. Spine 1999; 24:1556-

1561.

9. Carey TS, Garrett JM, Jackman A et al. Re-

currence and care seeking after acute

back pain. Results of a long-term follow-

up study. Medical Care 1999; 37:157-164.

10. Miedema HS, Chorus AM, Wevers CW,

et al. Chronicity of back problems dur-

ing working life. Spine 1998; 23:2021-

2029.

11. Thomas E, Silman AJ, Croft PR et al. Pre-

dicting who develops chronic low back

pain in primary care. A prospective study.

Brit Med J 1999; 318:1662-1667.

12. Wahlgren DR, Atkinson JH, Epping-Jor-

dan JE et al. One-year follow up of first

onset low back pain. Pain 1997; 73:213-

221.

13. Schiottz-Christensen B, Nielsen GL, Han-

sen VK et al. Long-term prognosis of acute

low back pain in patients seen in general

practice: A 1-year prospective follow-up

Author Affiliation:

Mark V. Boswell, MD, PhD

Chief Division of Pain Medicine

Department of Anesthesiology

Case Western Reserve University

School of Medicine and University

Hospitals of Cleveland

11100 Euclid Avenue

Cleveland, Ohio, 44106

E-mail: [email protected]

Hans C. Hansen, MD

Medical Director

The Pain Relief Centers, PA

3451 Greystone Place SW

Conover, North Carolina 28613

E-mail: [email protected]

Andrea M. Trescot, MD

Medical Director

The Pain Center

1895 Kingsley Ave. Suite 903

Orange Park, Florida 32073

E-mail: [email protected]

Joshua A. Hirsch, MD

Harvard School of Medicine

Department of Interventional

Radiology

Massachusetts General Hospital

55 Blossom St. Gray 289

Boston, Massachusetts 02114

E-mail: [email protected]

Boswell et al • A Systematic Review of Epidural Steroids330

Pain Physician Vol. 6, No. 3, 2003

Boswell et al • A Systematic Review of Epidural Steroids 331

Pain Physician Vol. 6, No. 3, 2003

study. Fam Pract 1999; 16:223-232.

14. Ferguson SA, Marras WS, Gupta P. Lon-

gitudinal quantitative measures of the

natural course of low back pain recovery.

Spine 2000; 25:1950-1956.

15. Vingård E, Mortimer M, Wiktorin C et al.

Seeking care for low back pain in the

general population: A two-year follow-up

study: Results from the MUSIC-Norrtalje

Study. Spine 2002; 27:2159-2165.

16. Hildingsson C, Toolanen G. Outcome after

soft-tissue injury of the cervical spine: A

prospective study of 93 car accident vic-

tims. Acta Orthop Scand 1990; 61:357-

359.

17. Hodgson S, Grundy M. Whiplash injuries:

Their long-term prognosis and its relation-

ship to compensation. Neuro Orthopedics

1989; 7:88-91.

18. Paul R, Haydon RC, Cheng H et al. Poten-

tial use of sox9 gene therapy for interver-

tebral degenerative disc disease. Spine

2003; 28:755-763.

19. CDC. Prevalence of disabilities and asso-

ciated health conditions among adults –

United States, 1999. MMWR 2001; 50:120-

125.

20. Leigh JP, Markowitz S, Fahs M et al. Oc-

cupational injury and illness in the Unit-

ed States. Estimates of costs, morbidity,

and mortality. Arch Intern Med 1997; 157:

1557-1568.

21. Freedman VA, Martin LG, Schoeni RF. Re-

cent trends in disability and functioning

among older adults in the united states.

JAMA 2002; 288:3137-3146.

22. Wheeler AH, Murrey DB. Chronic lumbar

spine and radicular pain: Pathophysiolo-

gy and treatment. Curr Pain Headache Rep

2002; 6:97-105.

23. Antoniou J, Steffen T, Nelson F et al. The

human lumbar intervertebral disc: Evi-

dence for changes in the biosynthesis

and denaturation of the extracellular ma-

trix with growth, maturation, ageing, and

degeneration. J Clin Invest 1996; 98:996-

1003.

24. Buckwalter JA. Aging and degeneration of

the human intervertebral disc. Spine 1995;

20:1307-1314.

25. Guiot BH, Fessler RG. Molecular biology of

degenerative disc disease. Neurosurgery

2000; 47:1034-1040.

26. Mixter WJ, Ayers JB. Herniation or rupture

of the intervertebral disc into the spinal ca-

nal. N Engl J Med 1935; 213:385-395.

27. Mixter WJ, Barr JS. Rupture of the interver-

tebral disc with involvement of the spinal