Binghamton University Binghamton University

The Open Repository @ Binghamton (The ORB) The Open Repository @ Binghamton (The ORB)

Public Administration Faculty Scholarship Public Administration

Spring 4-25-2023

Public Sector Leadership During the COVID-19 Crisis in Ghana Public Sector Leadership During the COVID-19 Crisis in Ghana

Komla D. Dzigbede

Binghamton University--SUNY

Anthony M. Ivanov

Binghamton University--SUNY

Follow this and additional works at: https://orb.binghamton.edu/public_admin_fac

Part of the Economic Policy Commons, Public Administration Commons, and the Public Policy

Commons

Recommended Citation Recommended Citation

Dzigbede, K.D. and Ivanov, A.M. (2023), "Public sector leadership during the COVID-19 crisis in Ghana",

International Journal of Public Leadership, Vol. 19 No. 2, pp. 142-157. https://doi.org/10.1108/

IJPL-05-2022-0028

This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Public Administration at The Open Repository @

Binghamton (The ORB). It has been accepted for inclusion in Public Administration Faculty Scholarship by an

authorized administrator of The Open Repository @ Binghamton (The ORB). For more information, please contact

Public Sector Leadership During the COVID-19 Crisis in Ghana

Komla D. Dzigbede and Anthony M. Ivanov

State University of New York at Binghamton

Citation:

Dzigbede, K. & Ivanov, A. (2023). “Public sector leadership during the COVID-19 crisis in

Ghana.” International Journal of Public Leadership. https://doi.or g/10.1108/IJPL-05-2022-0028

International Journal of Public Leadership

Public Sector Leadership During the COVID-19 Crisis in

Ghana

Journal:

International Journal of Public Leadership

Manuscript ID

IJPL-05-2022-0028.R2

Manuscript Type:

Research Paper

Keywords:

Public sector leadership, COVID-19 crisis, central bank, Ghana,

Developing countries

International Journal of Public Leadership

International Journal of Public Leadership

1

Public Sector Leadership During the COVID-19 Crisis in Ghana

Abstract

Purpose: This article examines public sector leadership during the economic crisis caused by the

coronavirus pandemic in Ghana. It focuses on the Bank of Ghana–the nation’s central bank

responsible for monetary policy and financial sector leadership–and examines the critical

leadership attributes that the central bank demonstrated through its administrative and policy

responses to the crisis.

Design/methodology/approach: Text-based content analysis is the method of investigation in

this study. The analysis relies on textual data from the Bank of Ghana’s monetary policy

committee press briefings. The textual data are analyzed in three steps, namely pre-analysis,

analysis, and interpretation to identify patterns, themes, and emphases and to make inferences

about the central bank’s public sector leadership during the coronavirus crisis in Ghana.

Findings: The findings from textual analysis of monetary policy committee press briefings show

that the central bank demonstrated several criteria of effective public service leadership during

the crisis, namely sensemaking, critical decision-making, communication, accountability,

adaptability and, to an extent, learning. However, the textual evidence suggests that the Bank of

Ghana needs to broaden its collaboration and coordination across a wider spectrum of

stakeholders in economic crisis management, while not compromising its policy independence.

Originality: This article contributes to the emerging literature on public sector leadership during

the COVID-19 crisis. It provides a unique perspective on public sector leadership through the

lens of economic crisis management in a developing country context.

Keywords: Public sector leadership, COVID-19 crisis; central bank; Ghana; developing

countries

Page 8 of 38International Journal of Public Leadership

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

International Journal of Public Leadership

2

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has refocused attention on public sector leadership in times of

crises. Scholars have described the coronavirus pandemic as a unique and wicked problem–even

a super wicked problem–in public policy (Schiefloe 2021). Wicked problems have no proven

solutions, and policymakers’ attempts at solutions may have incalculable and irreversible

consequences (Rittel & Webber 1973). Moreover, super wicked problems rapidly spin out of

control with irreversible consequences, do not allow time for traditional processes of policy and

politics, and worse still the actors, organizations and institutions tasked with finding solutions

may at the same time contribute negatively to the rapidly evolving problem (Levin, Cashore,

Bernstein et al. 2012).

With the coronavirus pandemic, the scope and depth of the crisis has required that public

service organizations and their leaders provide adaptive leadership that demonstrates long-

established criteria for effective public sector leadership, including early recognition,

sensemaking, critical decision-making, vertical and horizontal coordination, communication,

rendering accountability, learning, and enhancing resilience (Boin, Kuipers & Overdijk 2013;

Mergel, Ganapati & Whitford 2021). The pandemic also highlighted the need for public sector

organizations and their leaders to demonstrate innovative institutional leadership by

implementing new strategies in response to emergent challenges, while not deviating from the

core values of the organization (Selznick 1957; Washington, Boal & Davis 2008; Strumińska-

Kutra & Askeland 2020).

This article attempts to address the question: what characterizes effective public sector

leadership during a major economic crisis in a country? The article engages this question through

the administrative and policy actions of a central bank during the economic crisis caused by the

Page 9 of 38 International Journal of Public Leadership

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

International Journal of Public Leadership

3

COVID-19 pandemic in a developing country. Central banks around the world provide critical

leadership in national economic management by formulating and implementing monetary policy,

ensuring financial system soundness, and supporting long-term economic resilience. Moreover,

during major crises like the coronavirus pandemic, the central bank’s administrative and policy

leadership are critical to reduce economic shocks and spur economic recovery, especially in

developing countries where central banks tend to have limited political autonomy (Arnone,

Laurens, Segalotto & Sommer 2009; Garriga & Rodriguez 2020).

In the Africa region, for example, central banks provided critical support for government

efforts to mitigate the impacts of the coronavirus pandemic. The Central Bank of Kenya lowered

its monetary policy rate consistently to encourage economic activity and mitigate the slowdown

in the economy due to the coronavirus crisis (International Monetary Fund 2022). It also

implemented macro-financial measures, including lowering deposit money banks’ cash reserve

requirement, to support commercial lending to the private sector and promote economic activity.

In addition, the central bank provided USD 69 million (amounting to 0.08 percent of GDP) to the

government to support the fight against the coronavirus crisis (Collaborative Africa Budget

Reform Initiative 2022).

Another notable example is Nigeria, where the central bank consistently lowered the

monetary policy rate to encourage economic activity and injected significant liquidity

(amounting to USD 8.3 billion or 2.4 percent of GDP) into the banking system to support lending

to critical sectors of the economy (International Monetary Fund 2022). Meanwhile in Ghana, the

central bank made emergency financing provisions for the government to borrow USD 1.7

billion (or 2.6 percent of GDP) from the central bank to support the government’s crisis response

efforts. The central bank also provided domestic financing for the government to grant interest-

Page 10 of 38International Journal of Public Leadership

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

International Journal of Public Leadership

4

free and soft loans to qualified micro, small, and medium-sized enterprises affected by the

coronavirus crisis (Collaborative Africa Budget Reform Initiative 2022).

This article focuses on the Bank of Ghana, the central bank in Ghana, and analyzes

textual data from the bank’s economic policy press releases during the COVID-19 crisis to

understand what characterizes effective public sector leadership during a major economic crisis

in a developing country context. It draws from adaptive leadership theory to develop a

framework of public sector leadership characteristics and uses this framework to identify the

specific criteria of adaptive leadership that the central bank displayed in managing the crisis. It

also draws insights from institutional leadership theory as a lens to enhance understanding of the

central bank’s economic crisis management. As a case study, this article focuses on the Bank of

Ghana because it is the frontier public service organization in Ghana responsible for formulating

and implementing economic and financial policy. In addition, the Bank of Ghana’s

administrative and policy responses to the COVID-19 economic crisis in Ghana represents the

common responses of central banks in similar developing countries dealing with the implications

of the crisis in their economies. Thus, insights from Bank of Ghana’s case study can inform

public sector leadership in times of crisis in similar developing countries. Indeed, effective

public sector leadership is needed especially in times of crisis to mitigate the immediate and

long-term impacts of a crisis and support economic resilience to future crises.

The findings from textual analyses suggest that the Bank of Ghana, through its

administrative and policy responses to the COVID-19 economic crisis, demonstrated several

criteria of adaptive and effective public sector leadership, including sensemaking of the crisis,

critical decision-making, adaptability and, to some extent, learning. The findings also give

evidence of institutional leadership to the extent that central bank demonstrated a propensity to

Page 11 of 38 International Journal of Public Leadership

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

International Journal of Public Leadership

5

implement new measures in response to emergent threats in the economy, while not deviating

from its core mandate of monetary policy leadership. However, the findings also show that the

central bank needs to demonstrate more engagement, collaboration, and coordination with a

broad spectrum of stakeholders to deepen the impacts of the bank’s administrative and policy

responses in times of crisis.

The article is organized into six sections. The next section briefly discusses the

coronavirus-related economic crisis in Ghana and summarizes the Bank of Ghana’s

administrative and policy responses to the crisis. Section 3 discusses the academic literature on

public sector leadership in times of crises. Section 4 describes the textual data and empirical

methods for analyzing public sector leadership during the coronavirus-induced economic crisis

in Ghana. Section 5 discusses the empirical findings, and Sections 6 concludes and offers

insights for public sector leadership during major crises in developing countries.

The COVID-19 Crisis and Leadership Responses in Ghana

Like many developing countries, the coronavirus crisis caused severe challenges in Ghana’s

economy mainly due to disruptions in international trade flows and slowdown in exports of

goods and services. On March 14, 2020, the World Health Organization declared the coronavirus

a global health crisis as the number of virus infections spiraled worldwide. Ghana started to

experience severe disruptions in its major exports, including cocoa and crude oil, as early as

April 2020 as global economic activity slowed due to the pandemic. Bank of Ghana data show

that after many months of steady prices, the world price of cocoa declined significantly on a

year-on-year basis in April 2020 (1.9%), and even worse in June 2020 (5.8%), due to the

coronavirus pandemic and related disruptions in international commodity markets (Bank of

Ghana 2020). In addition, the world price of Brent crude oil declined massively and consistently

Page 12 of 38International Journal of Public Leadership

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

International Journal of Public Leadership

6

in year-on-year terms, starting in February (13.9%) and continuing in March (49.7%) and April

(62.8%) of 2020.

As with many developing countries that rely heavily on exports of commodities for

foreign exchange earnings, the protracted decline in the prices of Ghana’s major exports as the

coronavirus crisis deepened caused a decline in foreign exchange earnings and limited the

resource envelope needed to moderate shocks and sustain the domestic economy.

Unsurprisingly, real sector activity in the domestic economy plummeted in reaction to the global

pandemic. The country had recorded strong growth in gross domestic product in the first quarter

of 2020 (6.8%), but this was reversed in the second (-5.9%) and third (-3.1%) quarters of that

same year due to the impacts of the coronavirus crisis in the domestic economy, and even after

massive governmental and policy interventions, the economy only rebounded modestly (3.3%) at

the end of the year (Bank of Ghana 2021).

The Central Bank of Ghana’s Administrative and Policy Responses

Central banks in developing countries used a wide range of administrative and policy strategies

to mitigate the immediate impacts of the coronavirus crisis and support long-term economic

growth and resilience. The strategies included interest rate changes (policy rate cuts), lending

operations (targeted lending and liquidity provision), reserves management (changes in reserve

requirement ratios and compliance framework), asset purchases (government bonds), and foreign

exchange operations, including swap agreements (Cantú, Cavallino, De Fiore and Yetman 2021).

In Ghana, the Bank of Ghana reduced the policy rate from 16.0% to 14.5% in March

2020. The central bank’s monetary policy response was aimed at signaling the risks in the

economic outlook due to the potential impacts of the coronavirus crisis on net exports, foreign

exchange receipts, and domestic tax revenues (Bank of Ghana 2020a). The central bank, in

Page 13 of 38 International Journal of Public Leadership

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

International Journal of Public Leadership

7

addition, reduced the primary reserve requirement for banks from 10% to 8% and lowered

banks’ capital conservation buffer threshold from 3.0% to 1.5%. Together, the lowering of the

reserve requirement and capital conservation buffer threshold would give banks more liquidity

and financial space to support lending to critical sectors of the economy (Bank of Ghana 2020a).

Later in September 2020, the central bank maintained the policy rate at 14.5% to re-emphasize

its earlier monetary policy stance about the risks in the economic outlook and to encourage

growth-enhancing economic activities (Bank of Ghana 2020b). Concurrently, the central bank

secured $1 billion from the U.S. Federal Reserve’s Foreign and International Monetary

Authorities (FIMAs) facility, which gives central banks in foreign countries the opportunity to

improve their foreign exchange reserves by temporarily exchanging their U.S. Treasury

securities holdings for dollars from the Federal Reserve, even though the foreign central bank is

required to repurchase the securities at maturity (U.S. Federal Reserve 2020).

Political Contexts for the Bank of Ghana’s Policy Responses

It is important to understand the governance and political contexts for central banks’

policy responses to the COVID-19 crisis. Developing country governments implemented

massive interventions to mitigate the adverse impacts of the coronavirus pandemic in their

economies, including national emergency declarations, border closures, quarantining of travelers

arriving from highly-affected countries, strict lockdown restrictions of mass gathering, social

distancing measures, compulsory mask wearing rules, training of medical workers, extension of

critical medical equipment and supplies to healthcare workers, strengthening capacities for

surveillance, diagnostic testing and clinical care, as well as public health information messaging

(World Health Organization 2020; Ayouni et al. 2021). Governments also engaged in extra-

budgetary expenditures to provide food relief and other direct social assistance programs for

Page 14 of 38International Journal of Public Leadership

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

International Journal of Public Leadership

8

individuals, families, and small businesses (de Villiers et al. 2020; Ejiogu et al. 2020; Dzigbede

& Pathak 2020).

In Ghana, the government closed the nation’s borders in March 2020 to restrict travel into

the country and implemented strict lockdown restrictions in the two largest cities, Accra and

Kumasi, but the government gradually eased restrictions in the following months as diagnostic

testing and clinical care of infected persons improved nationwide (Collaborative Africa Budget

Reform Initiative 2020). Another important aspect of the government’s coronavirus response

involved the mass distribution of food packages to about one million people in areas under

movement restrictions, and the government paid 3 months’ water bills for needy households in

areas under lockdown restrictions (Ministry of Gender, Children & Social Protection 2020). The

government also committed $100 million to provide test kits, medical equipment, and medical

supplies as well as additional hospital beds countrywide to enhance the crisis response (Ministry

of Finance 2020). In addition, the National Health Insurance Agency (NHIA) benefited from a

$51 million government transfer to provide more support for pharmaceutical firms and

healthcare providers helping with crisis mitigation (Ministry of Health 2020).

Importantly, the Government of Ghana’s crisis intervention emphasized political

coordination and cooperation with many stakeholders in the country, including the scientific

community (to ground public health measures in robust scientific knowledge), faith-based

organizations (to support the provision of food packages to needy individuals and families during

lockdown restrictions), local manufacturing companies (to help with the production of personal

protective equipment for public health workers), and business and trade associations as well as

commercial and rural banks (to roll-out soft loans for micro, small and medium scale businesses)

- see Government of Ghana (2020). The crisis response actions of the Government of Ghana

Page 15 of 38 International Journal of Public Leadership

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

International Journal of Public Leadership

9

explain the governance and political contexts for the Bank of Ghana’s administrative and policy

leadership during the COVID-19 economic crisis.

Literature Review

The academic literature has explored the criteria for effective public sector leadership

during major crises. Scholarship on leadership theory, particularly adaptive leadership theory,

provides a useful foundation for identifying the leadership characteristics that are critical for

responding adequately to emerging challenges. Adaptive leadership defines a need for public

leaders to recognize and interact with flexibility in their contextual environments (Glover et al.

2002). It requires that public leaders learn and utilize new strategies in increasingly challenging

environments where traditional problem-solving routines and processes are no longer effective,

but creative problem-solving is needed as well as agility to alter course when necessary (Heifetz,

Linsky & Grashow 2009). Adaptive leadership therefore incorporates anticipation of future

needs, articulation of those needs to build collective understanding, adaptation through

continuous learning, and accountability in decision-making processes (Ramalingam et al. 2020).

Studies on leadership theory have also incorporated ideas on institutional leadership. An

institution may be defined as the set of core values that infuse an organization with a greater

sense of legitimacy and indispensability in the public sector (Selznick 1957). Accordingly,

institutional leadership entails a commitment to maintaining the core values of an organization

and developing external support mechanisms to enhance the organization’s legitimacy and

overcome external threats to achieving its mission (Washington, Boal & Davis 2008). However,

an organization may overemphasize actions that maintain consistency with its core values, and it

may struggle to meet new challenges because institutional precedents may be insufficient in

addressing emergent crises. Innovative institutional leadership therefore recognizes the need for

Page 16 of 38International Journal of Public Leadership

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

International Journal of Public Leadership

10

new practices and offers organizational space where these value-based practices can be

implemented along with older practices to solve emergent problems (Strumińska-Kutra &

Askeland 2020).

Scholars have used adaptive leadership theory and institutional leadership theory as

lenses to identify different criteria for effective public sector leadership in times of crises. These

criteria include: (1) early recognition (of the crisis needing immediate attention), (2)

sensemaking (of the nature, scope, and potential impact of the crisis), (3) critical decision-

making (at the highest levels of governance and decision-making), (4) vertical and horizontal

coordination (across different units and stakeholders), (5) meaning making (that interprets the

crisis situation and presents a plan of restoration from crisis to normalcy), (6) communication

(with citizens and between organizations and among governments), (7) learning (both during and

after crisis to correct dysfunctional processes and adapt to newly discovered solutions), and (8)

enhancing resilience by being flexible, adapting rapidly, and recovering quickly from crisis

(Boin & ‘t Hart 2003; McConnell 2011; Boin, Kuipers & Overdijk 2013; McConnell & ‘t Hart

2019). Thus, this paper uses the above set of criteria on adaptive and institutional leadership as a

theoretical framework to identify the specific characteristics of public sector leadership that the

Bank of Ghana displayed when managing the impacts of the COVID-19 economic crisis in

Ghana.

Research shows that the scope and depth of the coronavirus crisis required public service

organizations and their leaders to provide agile leadership that demonstrates long-established

criteria for effective leadership in the public sector (Ansell, Sørensen & Torfing 2020). Agility

refers to an institution’s capacity to respond to changing public needs in an efficient and

effective way, and agile leadership must combine with other established criteria for effective

Page 17 of 38 International Journal of Public Leadership

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

International Journal of Public Leadership

11

leadership, such as adaptability, responsiveness, and resilience, to promote robust governance

outcomes in times of crises (Mergel, Ganapati & Whitford 2021; Dzigbede, Gehl & Willoughby

2020).

Accordingly, studies examining governments’ responses to the coronavirus pandemic

have identified agility and responsiveness as key characteristics of effective mitigation. Moon

(2020) notes that the South Korea government’s agile and adaptive approach in crisis response

helped the country to contain the spread of the coronavirus in a minimally disruptive manner,

compared to other governments that enforced more hardline measures but could not effectively

reduce the rising number of infections. Similarly, Jamieson (2020) finds that the New Zealand

government adapting rapidly to changing circumstances in response to the pandemic contributed

to a stronger mitigation campaign in the country.

The emerging literature on the coronavirus crisis also emphasizes the need for public

sector leaders to consider institutional capacity, bureaucratic autonomy, and the political system

when managing crises (Petridou & Zahariadis 2021). This is because policy measures are not

entirely transferable from one country to another, and there may be different approaches to

achieving the same objective in different national contexts (Yan et al. 2021). In addition, the

literature asserts that effective leadership must incorporate a degree of prototyping or

experimentation, where public sector leaders make critical decisions before they have full

information, although such experimentation may challenge the typical hierarchical structures of

existing bureaucracies for crisis response (Ansell et al. 2020; Ansell & Boin 2017). However, as

experimentation gradually reveals new facts, public sector leaders must be willing to implement

new strategies based on knowledge from experts and learn as well as adapt accordingly to

enhance the effectiveness of their crisis response (Ansell et al. 2020).

Page 18 of 38International Journal of Public Leadership

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

International Journal of Public Leadership

12

Communication is also important for effective public sector leadership during crises.

Studies on leadership responses to the coronavirus crisis emphasize the need for public service

organizations to facilitate communication between their constituents and strengthen these micro-

level relationships to build institutional trust and foster greater buy-in for policy measures that

may otherwise be unpopular (Ansell et al. 2020; Mallinson 2020). This may necessitate

rethinking of the traditional framework for organization-constituent relationships and require that

public sector leaders “reconceptualize market exchange as a process of social construction in

which actors in self-organizing systems negotiate rules, norms, and institutional frameworks,

instead of taking the ‘rules of the market’ as given” (Bovaird 2006, p. 99). The emphasis on

more engagement with constituents tends to align well with the conception of the public sector

leader as a steward, which supports a more horizontal conception of the principal-agent

relationship where organizations seek common interests with constituents and work towards

collaborative solutions to achieve more effective service delivery in the public sector.

Importantly, the role of the public sector leader as a steward has been emphasized in the

literature examining effective leadership during the coronavirus pandemic (Ansell et al. 2020;

Jamieson 2020; Moon 2020).

Scholars in recent years have emphasized the need for more coordination in public sector

management, and have noted the importance of communication, engagement, and cooperation as

prominent mechanisms of coordination (Ahsan & Panday 2013). In developing countries,

especially, research shows that coordination is critical for administrative and policy actions, and

failure to consider important stakeholders–including the politics domain–in the design and

implementation of policies have resulted in the failure of policies in many countries (Dasandi

2014).

Page 19 of 38 International Journal of Public Leadership

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

International Journal of Public Leadership

13

Data and Methodology

This article uses content analysis as a method to understand the effective leadership

attributes that the Bank of Ghana demonstrated in its coronavirus crisis response in Ghana. The

content analysis is based on textual data from the Bank of Ghana’s Monetary Policy Committee

(MPC) press briefings. MPC press briefings are bi-monthly statements that provide details about

the central bank’s administrative and policy actions aimed at maintaining financial stability and

promoting economic resilience. Specifically, the analysis uses textual data from the central

bank’s press statements spanning November 2019 to January 2021. This period covers the

months leading up to when the World Health Organization declared the coronavirus crisis a

global pandemic (March 11, 2020) and Ghana recorded its first cases of the coronavirus (March

12, 2020). It also covers the months (March to December 2020) that marked the central bank’s

most immediate responses to the coronavirus-related economic crisis in Ghana.

Text-based content analysis consists of pre-analysis, analysis, and interpretation

(Richardson 1999) and is useful for identifying patterns, themes, contexts, and emphases in

textual data to make useful inferences (Zhang & Wildemuth 2012; Mayring 2014). It differs

from other forms of content analysis that rely on non-text-based sources, including photographs,

audios, videos, and website graphics (Pennington 2017). With text-based content analysis, the

researcher first identifies key words and phrases in the textual data based on a pre-determined

concept or theory and codes the key words and phrases to analyze their occurrences under the

main categories of the theory (Mayring 2014). Textual analysis also goes beyond key words and

phrases and examines excerpts from the text, together with their context and language, to deepen

understanding about the topic under investigation (Mayring 2021).

Page 20 of 38International Journal of Public Leadership

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

International Journal of Public Leadership

14

The text-based analysis in this study follows three main steps. The first step, or pre-

analysis stage, identifies key words and phrases in the textual data that indicate effective public

sector leadership during the coronavirus crisis in Ghana. To do this, this study draws from

existing research that identify the main attributes of effective public sector leadership in times of

crisis, including early recognition, critical decision-making, sensemaking, communication,

coordination, learning, accountability, and resilience (Boin, Kuipers & Overdijk 2013; Mergel,

Ganapati & Whitford 2021). The article then compiles the key words and phrases from the

textual data on Ghana that portray the critical leadership attributes identified in the academic

literature.

In the second step, or analysis stage, the key words and phrases are coded based on their

total occurrence (or counts) under each category or characteristic of public sector leadership. The

third step, or interpretation stage, assesses the frequency of occurrence of key words and phrases

related to each characteristic of public sector leadership and interprets what these statements

indicate about leadership in the Bank of Ghana’s coronavirus crisis response. Importantly, the

interpretation stage in this paper goes beyond key words and phrases and considers excerpts from

the text, as well as their context and language, to provide a deeper understanding of the Bank of

Ghana’s public sector leadership in times of crisis. The text-based content analysis in this study

therefore consists of two interrelated elements, namely: (1) an analysis of words and phrases in

the textual data using word frequency tables and word cloud visualization and (2) an examination

of word groups, passages, and excerpts as well as the contexts informing these statements.

However, one major limitation of using text-based content analysis in our study is that

the texts include statements about the planned actions of the central bank, and these may not

Page 21 of 38 International Journal of Public Leadership

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

International Journal of Public Leadership

15

entirely represent the actual policy actions and real leadership traits of the central bank. Indeed,

effective public leadership is not merely about public sector leaders making policy statements;

rather, it requires that public leaders back their statements with robust actions to achieve

sustainable policy outcomes. Still, the textual analysis in this study provides a way to understand

the central bank’s latent leadership characteristics based on its own statements about the

administrative and policy actions to mitigate the COVID-19 economic crisis.

Results and Discussion

The results from text-based content analysis give unique insights on public sector leadership

during the COVID-19 crisis in Ghana. A textual analysis of the Bank of Ghana’s press

statements shows the central bank’s sensemaking of the crisis, critical decision-making, and

regular communication with the public as characteristics of effective leadership during the

coronavirus economic crisis. In addition, the textual analysis reveals that the central bank to an

extent demonstrated other critical leadership characteristics, including adaptability, learning and

resilience, when managing the coronavirus-related economic crisis.

Early recognition of a crisis is defined as an organization’s ability to identify ahead of

time the potential for crisis, and it requires the shared awareness that a crisis might occur, as well

as a willingness to act even on faint signals (Boin, Kuipers and Overdijk 2013). The Bank of

Ghana’s MPC press statements demonstrate the central bank’s early recognition of the major

risks the coronavirus crisis could cause to the national economy. The statements also

demonstrate the central bank’s continuing vigilance on the extent of potential economic effects

even at the early stages of the crisis.

Page 22 of 38International Journal of Public Leadership

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

International Journal of Public Leadership

16

“The key risks to the global growth outlook are geopolitical tensions between the US and Iran and

worsening of relations between the US and its trading partners with the rising threat of protectionism and

vulnerabilities in emerging markets. The outbreak of the Coronavirus poses a new risk to the global

economy and its impact is yet to be assessed.” (Bank of Ghana, MPC Press Statement, January 2020)

“In the assessment of the Bank, the negative impact of COVID-19 on exports, imports, taxes, and foreign

exchange receipts will culminate in a slowdown in economic activity. GDP growth is forecasted to decline

to 5.0 percent in a baseline scenario. In the worst case scenario, GDP growth estimates could be halved to

about 2.5 percent in 2020.” (Bank of Ghana, MPC Press Statement, March 2020)

Sensemaking during a crisis means to arrive at a collective understanding of the nature,

characteristics, potential scope, and consequences of an evolving crisis, and to create a dynamic

picture of the crisis that all stakeholders understand (Boin, Kuipers & Overdijk 2013). It is a

more adaptive method of gaining understanding in evolving situations than simply knowing,

which can be constrained by routine. Sense making therefore goes beyond knowing to consider

the time, place, and contexts that provide more meaning about a policy problem (Dervin 1998).

The Bank of Ghana’s sensemaking of the COVID-19 crisis was evident to a reasonable extent in

the MPC statements as the central bank weighed the consequences of a protracted pandemic on

the domestic economy.

“The MPC noted that uncertainties in the global economy [have] increased, although investor uneasiness

improved somewhat. The uncertainty derives from a possibility of a prolonged downturn as countries begin

to experience a second wave of COVID-19 infections.” (Bank of Ghana, MPC Press Statement, July 2020)

“[In Ghana, the] pandemic has had a more negative impact in the first half of 2020 than anticipated and the

recovery is projected to be more gradual than previously projected.” (Bank of Ghana, MPC Press

Statement, July 2020)

Page 23 of 38 International Journal of Public Leadership

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

International Journal of Public Leadership

17

Making critical decisions during a crisis involves careful deliberation and following due

process to make strategic decisions at the highest levels of governance (Boin et al., 2005).

Additionally, communication during a crisis should explain the crisis and its impacts and must

provide timely and accurate information to the public about what is being done, and by whom

and why, to mitigate the impacts of the crisis (Fearn-Banks 2007). The Bank of Ghana made

strategic economic decisions about the COVID-19 crisis at its bi-monthly MPC meetings and

regularly communicated these high-level decisions to the public through televised press

briefings.

As part of its prudential supervision of the financial system during the coronavirus crisis

in Ghana, the Bank of Ghana demonstrated coordination and cooperation with banks and

specialized deposit-taking institutions. Coordination during a major crisis requires intense

cooperation among a variety of public service organizations and across vertical and horizontal

organizational borders (Boin & ’t Hart 2012). The textual data from the central bank’s press

briefings showed the apex bank’s commitment to provide guidance and liquidity support to

banks and specialized deposit-taking institutions to enhance soundness of the financial system.

“The Bank will provide guidance to banks and SDIs on the accounting treatment of loan restructuring,

classifications, provisioning, and expected credit losses, and prudential assessments of credit risk and

capital ratios.” (Bank of Ghana, MPC Press Statement, May 2020)

“The central bank will continue to engage the banking industry to provide the necessary support in these

challenging times.” (Bank of Ghana, MPC Press Statement, July 2020)

However, the textual data does not give sufficient evidence of the central bank’s

engagement, collaboration, and coordination with other important stakeholders besides the

banking industry in the management of the COVID-19 economic crisis. The central bank may

broaden its engagement and coordination in economic decision-making across a wider spectrum

Page 24 of 38International Journal of Public Leadership

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

International Journal of Public Leadership

18

of stakeholders, including local economic development councils, trade unions, industry, private

for-profit institutions, nonprofit organizations, civil society organizations, and retail and

institutional investors. In addition, there is not sufficient evidence from the textual data that the

central bank collaborated significantly with the politics domain in developing strategies to

counteract the economic impacts of the coronavirus crisis in Ghana.

The Bank of Ghana showed evidence of accountable leadership in the coronavirus crisis

management. Accountability requires that leaders present to the public a transparent and

constructive account of their actions and/or inactions before and during a crisis (Boin, Kuipers &

Overdijk 2013). The Bank of Ghana provided transparent and timely information on its

administrative and policy actions to mitigate the economic effects of the coronavirus crisis in

Ghana. The central bank’s MPC press briefings provided an interactive forum with the public to

communicate the central bank’s strategies and address questions from the public in a transparent

manner. Along with the press briefings, the central bank also made available to the public timely

economic data on the ongoing crisis as well as detailed information on threats to the medium-

term economic outlook.

Learning is the capacity to improvise, discover, and experiment both during and after a

crisis to correct dysfunctional processes and adapt to newly discovered solutions (Comfort 1999;

Boin et al 2013). It requires understanding the root causes of a policy problem and, even more

importantly, understanding the appropriate policy tools and techniques for solving the problem

(Howlett 2012; O'Donovan 2017). In the context of policymaking, learning can occur through

instrumental policy learning, social policy learning, or political learning (May 1992).

Instrumental learning generates new understanding about how a policy tool works, is designed,

or implemented to achieve desired outcomes. Social policy learning creates new understanding

Page 25 of 38 International Journal of Public Leadership

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

International Journal of Public Leadership

19

of a policy that leads to a change in the social construction of the policy problem as well as the

causal reasoning underpinning the definition of the problem. As for political learning, it

generates changes in knowledge about the effectiveness of policy strategies that policy advocates

use to draw attention to problems or advance policy ideas. Learning is effective when policy

leaders draw lessons from other jurisdictions that have encountered the same problem, and they

can learn by looking across time or geographical space (Rose 1991).

It appears that the Bank of Ghana actively gathered knowledge about the crisis response

strategies of other central banks in developed and emerging economies.

“In addition to the monetary policy actions, major advanced economies have also initiated fiscal stimulus

packages to minimize the impact of the coronavirus pandemic on the global economy. Several other emerging

market and frontier economies have replicated such fiscal measures to protect against the economic ramifications of

the pandemic.” (Bank of Ghana, MPC Press Statement, March 2020)

However, knowing does not necessarily equate to learning, and the central bank’s

knowledge about the policy actions of other central banks, which the central bank is expected to

know, does not necessarily mean it actively learned from their experiences to inform its domestic

policy strategies. At any rate, the extent to which the central bank displayed learning to a

reasonable degree in not fully measurable. It is too early yet to gauge the extent to which the

central bank’s crisis management processes make it possible for the bank to reflect on the effects

of its administrative and policy actions during the crisis. It is also quite early yet to assess the

extent to which the central bank may have reflected on whether its administrative actions and

policy strategies could have been implemented in a different way, based on the experiences from

other central banks, to achieve better outcomes.

Resilience requires that leaders continuously engage crisis preparedness practices before

a crisis occurs, and when a major crisis occurs, they must manifest a degree of flexibility and

Page 26 of 38International Journal of Public Leadership

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

International Journal of Public Leadership

20

capacity to adapt rapidly and recover speedily from the crisis (Comfort, Boin & Demchak 2010;

Boin et al. 2013). The Bank of Ghana’s MPC press briefings seem to suggest continued

monitoring and vigilance on the COVID-19 economic threats. The textual data also give

evidence of the central bank’s readiness to utilize additional administrative and policy measures,

if needed, to mitigate the impacts of the crisis. This propensity of the central bank to implement

new measures in response to emergent threats in the economy while not deviating from the core

mandate of monetary policy leadership seems to align with the notion of innovative institutional

leadership (Selznick 1957; Strumińska-Kutra & Askeland 2020).

“The Bank of Ghana is closely monitoring developments as regards the impact of COVID-19 on the

domestic economy, and will not hesitate to convene an emergency meeting to deliberate on other measures,

if required.” (Bank of Ghana, MPC Press Statement, March 2020)

“However, there are uncertainties in the external environment which need to be carefully monitored to

ensure that Ghana continues to safeguard international capital market access.” (Bank of Ghana, MPC Press

Statement, September 2020)

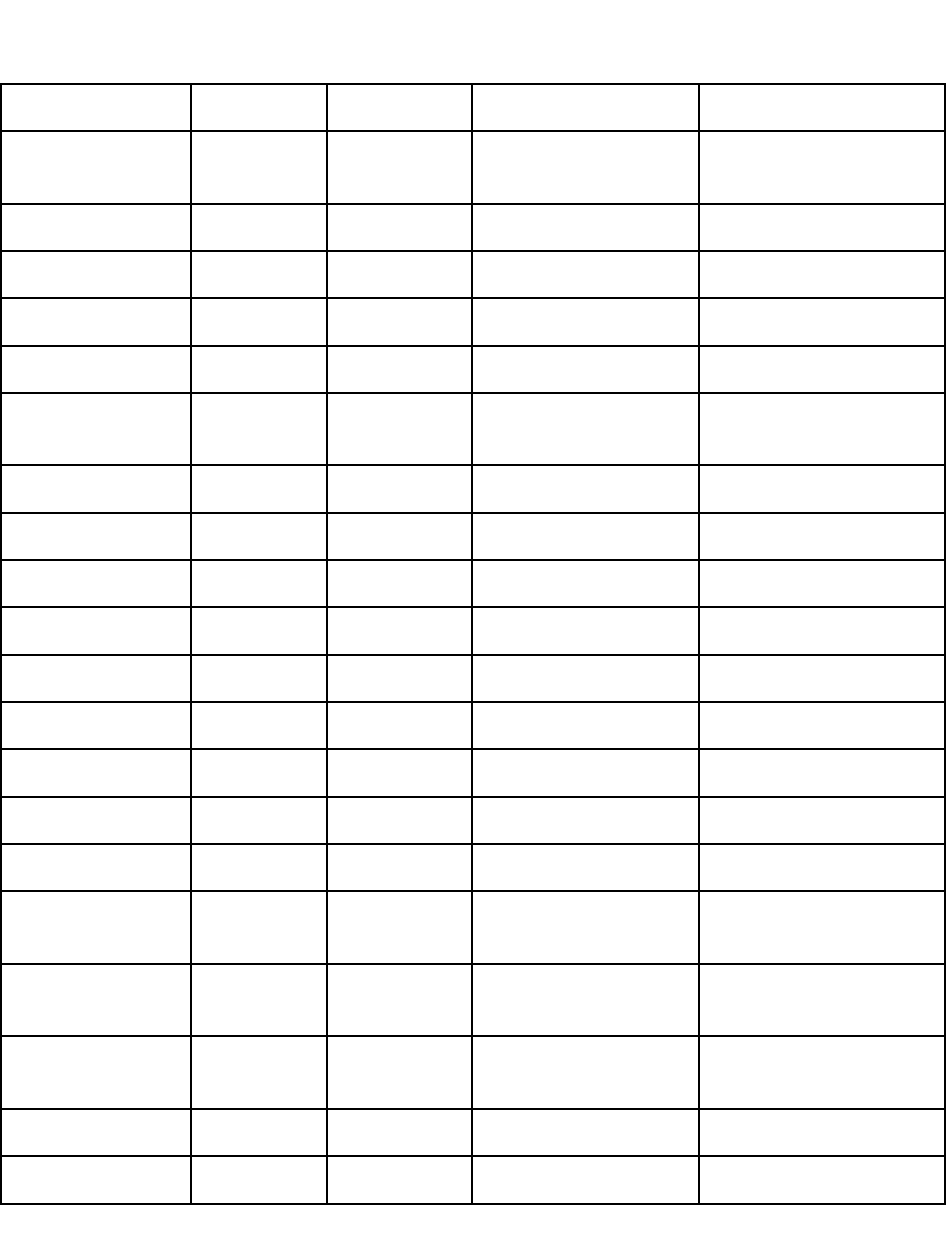

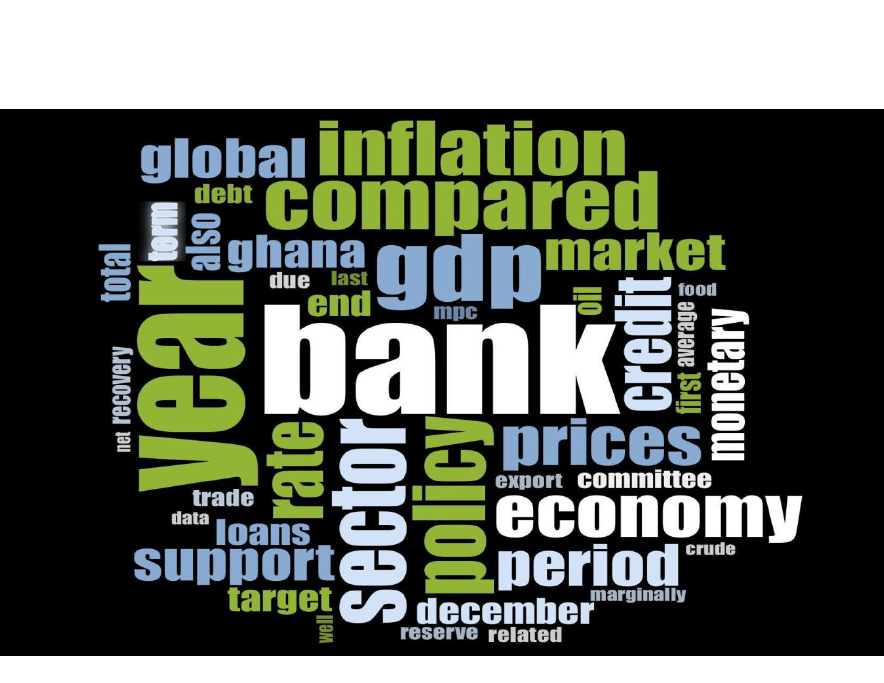

Further analysis of the Bank of Ghana’s press briefings demonstrates a strong focus on

mitigating the economic risks and uncertainties from the coronavirus crisis while supporting

economic recovery and resilience. Table 1 shows that across all 8 of its press briefings from

November 2019 to February 2021, the central bank showed much concern about the “global”

(0.60%) “pandemic” (0.53%) and related threats to “inflation” (0.82%), or “prices” (0.71%), and

gross domestic product (0.99%) or the “economy” (0.75%) or economic “growth” (1.20%). The

central bank press briefings also emphasized the significant role of the policy “rate” (0.71%) as a

tool for expansionary policies that can mitigate economic “decline” (0.55%) and “support”

(0.58%) recovery. The word-cloud visualization depicted in Chart 1 provides an alternative way

to understand the central bank’s emphases across all press briefings.

Page 27 of 38 International Journal of Public Leadership

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

International Journal of Public Leadership

21

[Table 1 about here]

[Chart 1 about here]

Summary and Insights for Public Sector Leadership

The coronavirus pandemic may be characterized as a wicked problem in public policy. It

spun rapidly out of control across countries and regions of the world and did not allow sufficient

time for nations to engage their traditional processes of administration, policy, and politics to

manage the pandemic. At the same time, the pandemic has required administrators,

policymakers, and politicians to demonstrate effective public sector leadership to mitigate the

immediate and long-term consequences of the pandemic and support economic resilience to

future crises.

This article analyzes public sector leadership in Ghana during the coronavirus crisis. It

investigates the leadership attributes that public sector managers demonstrated in national crisis

management. The article examines the crisis leadership characteristics of the Bank of Ghana, a

frontier public service organization responsible for formulating and implementing financial and

economic policy. The findings suggest that the central bank demonstrated several characteristics

of adaptive public sector leadership during the coronavirus crisis, including critical decision-

making, communication, adaptability and, to a limited extent, learning. The results also show

institutional leadership to the extent that the central bank expressed a willingness to implement

new policy actions to address emergent threats in the economy, while maintaining its core

mandate of monetary policy leadership. However, the findings also show that the central bank

could do more to engage, collaborate, and coordinate with a broader spectrum of stakeholders in

economic crisis management.

Page 28 of 38International Journal of Public Leadership

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

International Journal of Public Leadership

22

This article offers several insights for public sector leadership during major crises in

developing countries. One important implication of our study is that when major crises like the

coronavirus pandemic occur, central banks and other autonomous or semi-autonomous public

sector organizations tasked with managing the economic impacts of the crisis must demonstrate a

wide range of effective leadership attributes to achieve sustainable outcomes. In the case of

central banks and their leadership role in national economic management, such critical leadership

must include established criteria such as early recognition and sensemaking of the crisis, careful

deliberation about which administrative and policy actions to take, coordination with multiple

stakeholders in the economy, regular communication with the public to disseminate timely and

correct information, rendering accountability, and adapting and learning from (in)actions before

and during the crisis to promote resilience to future crises. This insight from the article provides

a theoretical framework for gauging the effectiveness of public sector leadership in times of

crisis especially in developing country contexts.

Another insight for public policy derives from the relationship between politics and

administration in crisis management. The overriding consensus among scholars in recent years is

on the need for more engagement, coordination and collaboration between the politics and

administration domains in public sector management. Such coordination and collaboration are

even more important in crisis management. It would require that public administrators and

managers tasked with implementing government policies during a crisis collaborate and

coordinate with politicians as the latter mobilize broad-based support for government policies.

However, the challenge in developing countries is about achieving the right balance of

collaboration and coordination to limit the potential for undue political interference in the

administration and management domains of the public sector. In the case of the coronavirus

Page 29 of 38 International Journal of Public Leadership

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

International Journal of Public Leadership

23

crisis in Ghana, this study’s evidence that the central bank should do more to engage,

collaborate, and coordinate with the politics domain in crisis management must also consider that

the central bank may face undue political interference if the central bank undertakes extensive

collaboration and coordination with the politics domain when managing an economic crisis. This

is especially the case in developing countries where political interference may constrain the

autonomy of the central bank, and for this reason central banks must be depoliticized to enhance

their ability manage economic crises more effectively in accordance with their core mandate of

monetary policy leadership.

In addition, a central bank’s collaborative engagement with a broader spectrum of

stakeholders in economic crisis management can expose the central bank to new administrative

risks, such as financial data breaches, which can arise if the central bank on a real-time basis

disseminates sensitive financial information across collaborative networks in economic crisis

management. Nevertheless, in the case of Ghana, the central bank would benefit significantly

from more collaborative engagement with a broader span of stakeholders in economic decision-

making – including civil society organizations, local economic development councils, trade

unions, businesses and firms, nonprofit organizations, and institutional and retail investors – to

the extent that these collaborative networks provide the feedback that the central bank needs as

inputs for more effective economic decision-making in times of crisis.

Central banks, especially, serve a frontier role in national economic management and

their administrative and policy actions during major crises are critical to moderate economic

shocks; but all stakeholders must ensure the functional and policy independence of the central

bank even as collaboration and coordination with a broad spectrum of stakeholders are needed in

crisis management.

Page 30 of 38International Journal of Public Leadership

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

International Journal of Public Leadership

24

Page 31 of 38 International Journal of Public Leadership

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

International Journal of Public Leadership

25

References

Ahsan, A. K., & Panday, P. K. (2013). Problems of coordination in field administration in

Bangladesh: Does informal communication matter? International Journal of Public

Administration, 36(8), 588-599.

Ansell, C., Boin, A., & Keller, A. (2010). Managing Transboundary Crises: Identifying the

Building Blocks of an Effective Response System. Journal of Contingencies and Crisis

Management, 18(4), 195–207. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5973.2010.00620.x

Ansell, C., & Boin, A. (2017). Taming Deep Uncertainty: The Potential of Pragmatist Principles

for Understanding and Improving Strategic Crisis Management. Administration &

Society, 51(7), 1079–1112. https://doi.org/10.1177/0095399717747655

Ansell, C., Sørensen, E., & Torfing, J. (2020). The COVID-19 Pandemic as a Game Changer for

Public Administration and Leadership? The Need for Robust Governance Responses to

Turbulent Problems. Public Management Review, 23(7), 949–960.

https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2020.1820272

Arnone, M., Laurens, B. J., Segalotto, J. F., & Sommer, M. (2009). Central bank autonomy:

Lessons from global trends. IMF Staff Papers, 56(2), 263-296.

Ayouni, I., Maatoug, J., Dhouib, W., Zammit, N., Fredj, S. B., Ghammam, R., & Ghannem, H.

(2021). Effective public health measures to mitigate the spread of COVID-19: a

systematic review. BMC public health, 21(1), 1-14.

Bank of Ghana. Monetary Policy Committee Press Releases. Available at:

https://www.bog.gov.gh/

Boin, A., & ‘t Hart, P. (2003). Public leadership in times of crisis: mission impossible?. Public

Administration Review, 63(5), 544-553.

Boin, A., ‘t Hart, P. 't, Stern, E. K., & Sundelius, B. (2005). The Politics of Crisis Management:

Public Leadership Under Pressure. Cambridge University Press.

Boin, A., & ‘t Hart, P. (2012). Aligning executive action in times of adversity: The politics of

crisis co-ordination. In Executive politics in times of crisis (pp. 179-196). Palgrave

Macmillan, London.

Boin, A., Kuipers, S., & Overdijk, W. (2013). Leadership in Times of Crisis: A Framework for

Assessment. International Review of Public Administration, 18(1), 79–91.

https://doi.org/10.1080/12294659.2013.10805241

Bovaird, T. (2006). Developing New Forms of Partnership with the 'Market' in the Procurement

of Public Services. Public Administration, 84(1), 81–102.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0033-3298.2006.00494.x

CABRI (2022). COVID-19 Public Finance Response Monitor. Retrieved September 29, 2022,

from https://www.cabri-sbo.org/en/pages/covid-19-public-finance-monitor

Cantú, C., Cavallino, P., De Fiore, F., & Yetman, J. (2021). A global database on central banks'

monetary responses to Covid-19 (Vol. 934). Bank for International Settlements,

Monetary and Economic Department.

Collaborative Africa Budget Reform Initiative (2020), “Public finance response monitor”,

available at: https://www.cabri-sbo.org/en/pages/covid-19-public-finance-monitor

Comfort, L.K. (1999), Shared Risk: Complex Systems in Seismic Response, Elsevier Science

Ltd., Oxford.

Comfort, L. K., Boin, A., & Demchak, C. C. (Eds.). (2010). Designing resilience: Preparing for

extreme events. University of Pittsburgh.

Page 32 of 38International Journal of Public Leadership

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

International Journal of Public Leadership

26

Dasandi, N. (2014). The Politics-Bureaucracy Interface: Impact on Development Reform.

Developmental Leadership Program. https://www.dlprog.org/publications/research-

papers/the-politics-bureaucracy-interface-impact-on-development-reform

de Villiers, C., Cerbone, D., & Van Zijl, W. (2020). The South African Government's Response

to COVID-19. Journal of Public Budgeting, Accounting & Financial Management, 32(5),

797–811. https://doi.org/10.1108/jpbafm-07-2020-0120

Dervin, B. (1998). Sense‐making theory and practice: An overview of user interests in

knowledge seeking and use. Journal of Knowledge Management, 2(2), 36–46.

https://doi.org/10.1108/13673279810249369

Dzigbede, K. D., Gehl, S. B., & Willoughby, K. (2020). Disaster Resiliency of U.S. Local

Governments: Insights to Strengthen Local Response and Recovery from the COVID ‐19

Pandemic. Public Administration Review, 80(4), 634–643.

https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.13249

Dzigbede, K. D., & Pathak, R. (2020). COVID-19 Economic Shocks And Fiscal Policy Options

For Ghana. Journal of Public Budgeting, Accounting & Financial Management, 32(5),

903–917. https://doi.org/10.1108/jpbafm-07-2020-0127

Ejiogu, A., Okechukwu, O. and Ejiogu, C. (2020). Nigerian budgetary response to the COVID-

19 pandemic and its shrinking fiscal space: financial sustainability, employment, social

inequality and business implications. Journal of Public Budgeting, Accounting &

Financial Management, 32(5), 919-928. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPBAFM-07-2020-0101

Fearn-Banks, K. (2007). Crisis Communications. A Casebook Approach, 3rd edition.

Garriga, A. C., & Rodriguez, C. M. (2020). More effective than we thought: Central bank

independence and inflation in developing countries. Economic Modelling, 85, 87-105.

Glover, J., Rainwater, K., Jones, G., & Friedman, H. (2002). Adaptive leadership (part two):

Four principles for being adaptive. Organization Development Journal, 20(4), 18–38.

Government of Ghana. President of Ghana’s addresses on coronavirus crisis management.

Available at: https://presidency.gov.gh/index.php/briefing-room/speeches

Hafner, C. A., & Sun, T. (2021). The ‘Team of 5 million’: The Joint Construction of Leadership

Discourse during the COVID-19 pandemic in New Zealand. Discourse, Context &

Media, 43, 1-10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dcm.2021.100523

Heifetz, R. A., Linsky, M., and Grashow, A. (2009). The Practice of Adaptive Leadership: Tools

and Tactics for Changing Your Organization and the World. Harvard Business Press,

2009.

Howlett, M. (2012). The lessons of failure: Learning and blame avoidance in public policy-

making. International Political Science Review, 33(5), 539–555.

International Monetary Fund (2022). Policy Responses to COVID-19. Available at:

https://www.imf.org/en/Topics/imf-and-covid19/Policy-Responses-to-COVID-19

Jamieson, T. (2020). “Go Hard, Go Early”: Preliminary Lessons from New Zealand’s Response

to COVID-19. The American Review of Public Administration, 50(6-7), 598–605.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0275074020941721

Levin, K., Cashore, B., Bernstein, S., & Auld, G. (2012). Overcoming the tragedy of super

wicked problems: constraining our future selves to ameliorate global climate change.

Policy sciences, 45(2), 123-152.

Mallinson, D. J. (2020). Cooperation and Conflict in State and Local Innovation During COVID-

19. The American Review of Public Administration, 50(6-7), 543–550.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0275074020941699

Page 33 of 38 International Journal of Public Leadership

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

International Journal of Public Leadership

27

May (1992) May, P. J. (1992). Policy learning and failure. Journal of Public Policy, 12(4), 331–

354.

Mayring, P. (2014). Qualitative content analysis: Theoretical foundation, basic procedures and

software solution. Klagenfurt.

Mayring, P. (2021). Qualitative content analysis: A step-by-step guide. Qualitative Content

Analysis, 1-100.

McConnell, A. (2011). Success? Failure? Something in-between? A framework for evaluating

crisis management. Policy and Society, 30(2), 63–76.

McConnell, A., & ‘t Hart, P. (2019). Inaction and public policy: Understanding why

policymakers ‘do nothing’. Policy Sciences, 52, 645–661.

Mergel, I., Ganapati, S., & Whitford, A. B. (2021). Agile: A New Way of Governing. Public

Administration Review, 81(1), 161–165. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.13202

Ministry of Finance (2020), Republic of Ghana Ministry of Finance (2020), available at:

http://www.mofep.gov.gh/

Ministry of Gender, Children and Social Protection (2020), Republic of Ghana Ministry of

Gender, Children and Social Protection, available at: http://www.mogcsp.gov.gh/

Ministry of Health (2020), “Republic of Ghana Ministry of Health”, available at:

https://www.moh.gov.gh

Moon, M. J. (2020). Fighting COVID-19 with Agility, Transparency, and Participation: Wicked

Policy Problems and New Governance Challenges. Public Administration Review, 80(4),

651–656. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.13214

O'Donovan, K. (2017). Policy failure and policy learning: Examining the conditions of learning

after disaster. Review of Policy Research, 34(4), 537-558.

Pennington, D. R. (2017). Coding of non-text data. The Sage handbook of social media research

methods, 232-251.

Petridou, E. (2020). Politics and administration in times of crisis: Explaining the Swedish

response to the COVID‐19 crisis. European Policy Analysis, 6(2), 147–158.

https://doi.org/10.1002/epa2.1095

Ramalingam, B., Nabarro, D., Oqubay, A., Carnall, D. R., & Wild, L. (2021, August 31). 5

Principles to Guide Adaptive Leadership. Harvard Business Review. Retrieved August 8,

2022, from https://hbr.org/2020/09/5-principles-to-guide-adaptive-leadership

Richardson, R. (1999). Pesquisa social: métodos e técnicas [Social research: methods and

techniques]. São Paulo: Atlas.

Rittel, H. W., & Webber, M. M. (1973). Dilemmas in a general theory of planning. Policy

sciences, 4(2), 155-169.

Rose, R. (1991). What is lesson-drawing? Journal of Public Policy, 11(1), 3–30.

Schiefloe, P. M. (2021). The Corona crisis: a wicked problem. Scandinavian Journal of Public

Health, 49(1), 5–8. https://doi.org/10.1177/1403494820970767

Schillemans, T. (2013). Moving Beyond the Clash of Interests: On Stewardship Theory and the

Relationships between Central Government Departments and Public Agencies. Public

Management Review, 15(4), 541–562. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2012.691008

Selznick, P. (1957). Leadership in Administration: A Sociological Interpretation. Harper & Row.

Strumińska-Kutra, M., & Askeland, H. (2020). Foxes and Lions: How Institutional Leaders Keep