Big Fashion and Wall Street Cash In on Wage Theft

1

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This report is the product of close collaboration between AFWA and GLJ-ILRF.

Sahiba Gill (GLJ-ILRF) is the primary author. The research for this report was

made possible by the GLJ-ILRF and AFWA teams together with AFWA’s labor

partners in Bangladesh, Cambodia, India, Indonesia, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka.

Big Fashion and Wall Street Cash In on Wage Theft

2

n Spring 2020, at the height of the first lockdowns and economic upheaval

around the globe from COVID-19, the Knight family, the largest shareholder

in Nike, Inc., the world’s second largest fashion company, paid themselves

$74 million in dividends on their Nike, Inc. stock, adding to a $45 billion net

worth that makes them the 25

th

wealthiest family in the world at time of

writing.

At the same time, Diah,

1

who prints the famous Nike swoosh onto hundreds of

gloves a day in an Indonesian factory in Nike’s supply chain, saw her hours and

salary cut in half in Spring 2020, throwing her family into a financial crisis. Nike

has 1.2 million workers in its supply chain, and seven in ten are women.

Working in Nike’s supply chain, Diah could no longer afford meat or fish as she

struggled to make ends meet for her family. She worried about the possibility

of appearing ill at work, because her factory management might require her to

take a COVID swab test, which would have cost Diah half her monthly income

at the time.

Diah was just one of the millions of garment workers in the Global South who

lost their paychecks en masse in Spring 2020. Already working for wages barely

above the poverty line, these workers were laid off by the hundreds of

thousands from factories that supply Nike and other Big Fashion companies

and faced wage theft at an unprecedented scale, from illegal layoffs and

terminations to arbitrary pay cuts, unpaid wages for hours worked, and gender

discrimination. Big fashion companies including Nike triggered this crisis when

they canceled or drastically reduced orders en masse in response to economic

uncertainty during the initial months of the COVID pandemic. According to Asia

Floor Wage Alliance’s (AFWA) 2021 report Money Heist, which reported findings

from its 2020 survey of over 2000 garment workers, Big Fashion’s factory

workers lost roughly three months’ pay on average during the first year of the

pandemic. The impact on workers, families and communities that produce

products for the global giants was profound.

Yet a year into the pandemic in 2021, as garment workers struggled to survive,

Nike announced it had made the largest profits in its history. Nike continues to

thrive — as recently as December 2022, the corporate giant enjoyed its best

quarterly revenue growth in a decade. Nike is not alone. In the fashion industry,

20 giant corporations generate 98% of the industry’s economic value, hence

the name “Big Fashion.” Big Fashion is making its highest profits in over a

decade. As we approach the pandemic’s three-year mark, Big Fashion has more

than recovered from COVID, while workers on their supply chains are still

reeling from the impacts.

In 2022, AFWA, an alliance of garment sector trade unions in South and

Southeast Asia, revisited factories from its 2020 survey to see if garment

1

Diah’s name has been anonymized to protect against retaliation. She is a member of an AFWA-

affiliated union in Indonesia.

I

Big Fashion and Wall Street Cash In on Wage Theft

3

workers have shared in Big Fashion’s pandemic recovery. They have not.

Instead, the AFWA found that workers have been stuck in an ongoing crisis that

keeps getting worse:

● Nine in ten revisited factories have not resolved workers’ COVID wage

claims from 2020, representing $71 million;

● Most revisited factories have new and ongoing wage violations since 2020:

○ More than half (22 of 41 factories) are not paying workers owed

overtime;

○ One in five factories (8 of 41 factories) are not paying workers

minimum wages or owed benefits.

These wage claims are likely just the tip of the iceberg, representing a small

portion of the expansive supply chains that produce clothing for Nike, and

other companies like Levi Strauss & Co. (aka Levi’s) and VF Corporation (aka

VF), which owns North Face, Supreme, Vans, Timberland, SmartWool and more.

In Big Fashion, widespread wage and hour violations have been called an “open

secret”, with Big Fashion companies contributing to the theft by squeezing

down labor costs at the factories in their supply chain.

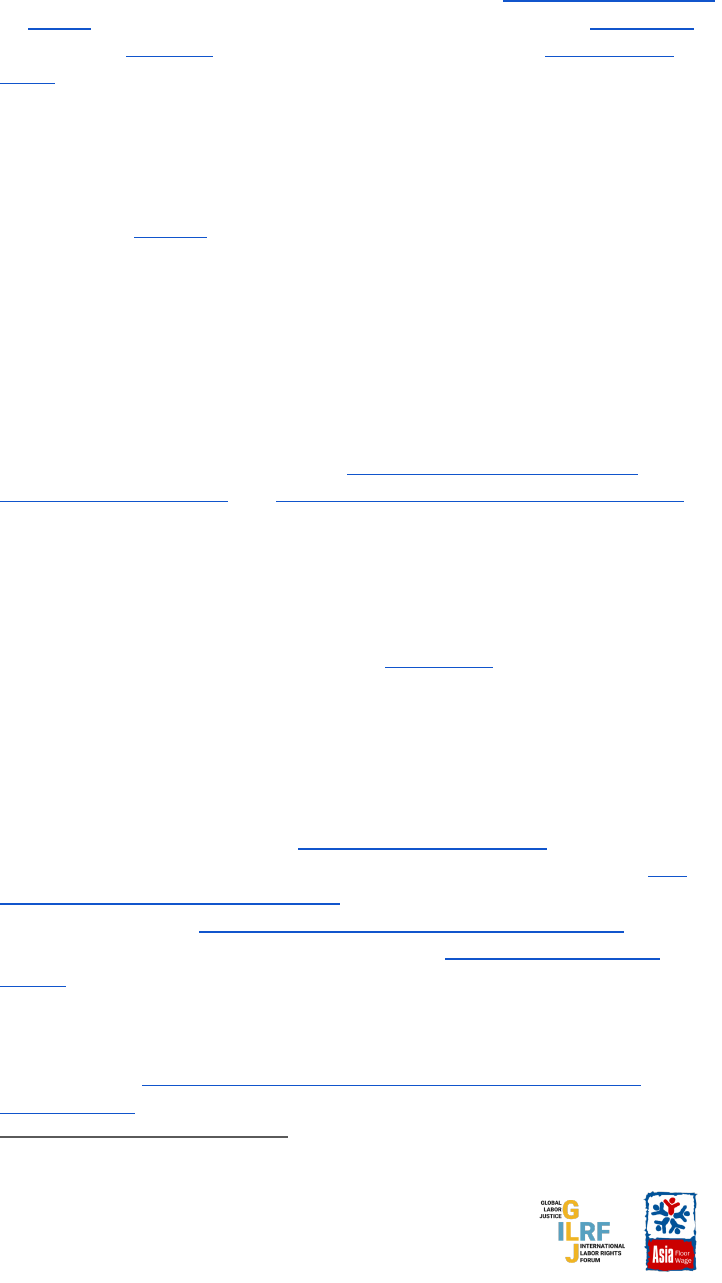

Table 1: COVID wage claims vs. Big Fashion dividends and buybacks

COVID wage claims at AFWA

surveyed factories, 2020

(USD)

Big Fashion dividends paid

to billionaire family

owners, Spring 2020 (USD)

Big Fashion stock

buyback authorizations,

as of January 2023

(USD)

Levi’s

$12.2 million

$19.7 million

$750 million

Nike

$9.3 million

$74 million

$18 billion

VF

$2.5 million

$34.4 million

$7 billion

2

But Nike’s pandemic profits have gone straight to Wall Street and billionaire

fashion company owners – not to workers who are waiting to be paid back for

wage theft. Nike did not only enrich investors through traditional dividends,

but by Spring 2021, a year after the start of the pandemic, Nike spent $650

million towards its $15 billion stock buyback program, a legal form of stock

manipulation that is widely considered bad for the economy and for workers.

Nike authorized a new $18 billion stock buyback program in 2022.

Nike is just one example. In this report, Big Fashion and Wall Street Cash In on

Wage Theft, Global Labor Justice-International Labor Rights Forum (GLJ-ILRF)

and the Asia Floor Wage Alliance (AFWA) detail the choice made by Big Fashion

– and particularly Nike, Levi’s and VF – to use the COVID-19 crisis and recovery

to enrich investors and billionaire family company owners, while leaving

2

VF, VF Corporation Introduces Fiscal Year 2027 Long-Term Strategic Plan and Financial Targets with

Revised Outlook for Fiscal Year 2023, https://www.vfc.com/news/press-release/1796/vf-corporation-

introduces-fiscal-year-2027-long-term. Note VF projects $7 billion in buybacks and dividends and

disaggregated figures are unavailable.

Big Fashion and Wall Street Cash In on Wage Theft

4

hundreds of thousands of garment workers in financial ruin. This was a choice.

As shown in Table 1, with a portion of just their payouts to billionaire family

owners and to investors via buybacks, several of Big Fashion’s giants could have

paid workers back for wage claims in their supplying factories many times over.

AFWA with affiliate garment worker unions have joined forces with GLJ-

ILRF and other international allies to demand that Big Fashion companies:

• Sit down with garment workers and their unions for a systematic

investigation of COVID wage claims, including specific impacts on

women workers.

• Stop billionaire payouts from dividends and stock buybacks until all

garment workers are repaid their lost wages.

• Transform their global supply chains to provide living wages for all

workers.

ORIGINAL “MONEY HEIST” CONTINUES DURING COVID RECOVERY

In 2021, AFWA released the findings of their 2020 survey of over 2000 garment

workers in six countries — Bangladesh, Cambodia, India, Indonesia, Sri Lanka,

and Pakistan — about the economic impact of Big Fashion’s actions during

COVID. At the 189 factories AFWA surveyed, workers lost at least an estimated

$164 million dollars in wages in 2020. In addition, the survey found that in

2020:

3

● One in ten workers lost their job permanently. Eight in ten fired workers

were not paid their severance benefits.

● Seven in ten workers were laid off.

● Seven in ten workers fell into poverty.

● Workers lost approximately three months of pay on average.

● Workers’ debt doubled to $420, roughly two to three months of pay.

● Three in five workers went into debt to pay for food.

● One in five workers went into debt to pay for rent.

● Workers who returned to work earned a quarter less than before COVID.

● Seven in ten workers who returned to work were not paid overtime rates

for overtime worked.

● Women garment workers made 82% of what male coworkers earned – an

increasing gender pay gap compared to earning 88% of male coworkers’

pay before COVID.

● Workers with temporary contracts lost more wages than workers with

permanent jobs.

At the end of 2022, AFWA returned to 41 factories in their original 2020 survey

to learn about the situation of workers two years later. Between August and

November 2022, AFWA and its trade union partners conducted site visits and

worker interviews to understand whether workers’ wage claims were resolved

3

Figures are calculated from original raw data from Money Heist, on file with authors.

Big Fashion and Wall Street Cash In on Wage Theft

5

and if factories were continuing to violate local laws and deny workers their

wages. AFWA also spoke to unions and workers about their efforts to get

remedy for wage violations at a local level.

At the revisited factories, workers’ reports to AFWA show (Table 2):

● Nine in ten factories have not resolved workers’ wage claims from 2020;

● More than half of factories are not paying workers owed overtime,

beginning in 2020 onward;

● One in five factories are not paying workers minimum wages or owed

benefits.

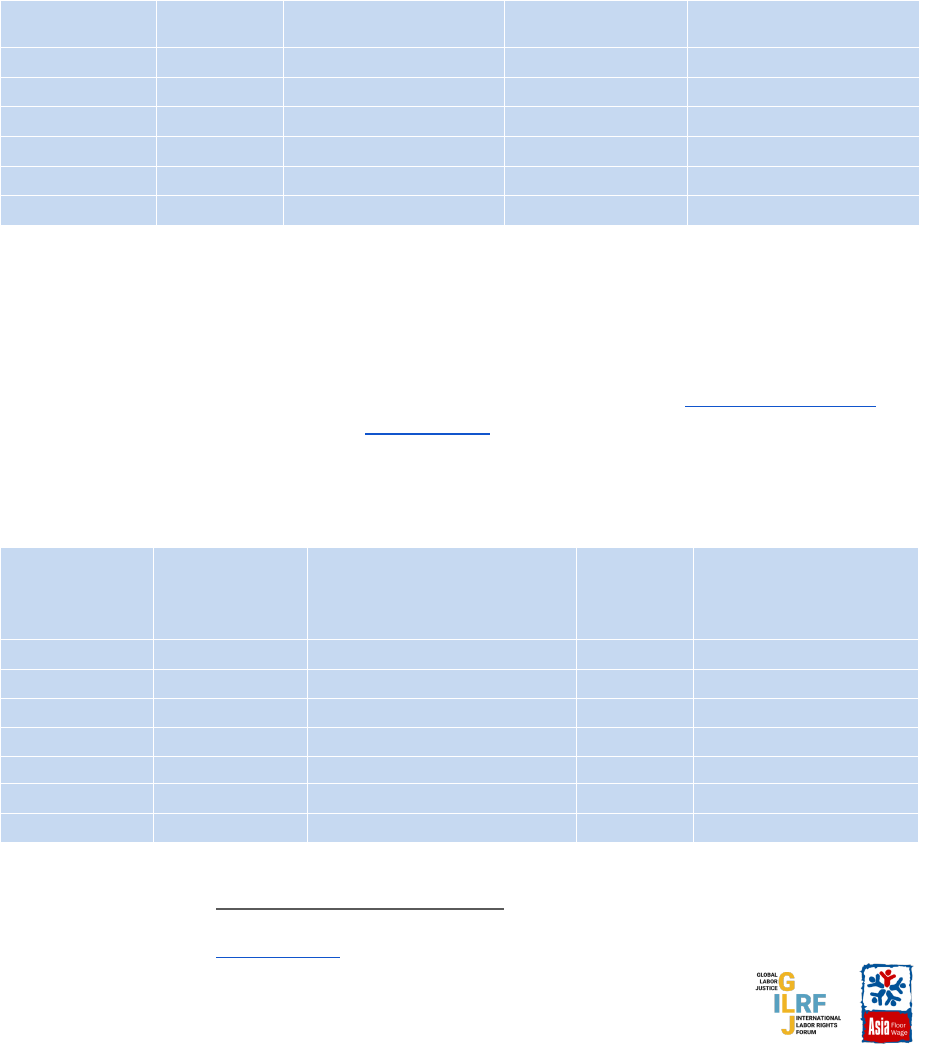

Table 2: Reviewed factories in 2022

Reviewed

factories

COVID wage claims

unresolved

New overtime

violations

New minimum wage or

benefits violations

Cambodia

5

5

0

0

India

10

9

4

4

Indonesia

8

8

0

3

Pakistan

15

13

15

2

Sri Lanka

3

3

3

0

TOTAL

41

38

22

9

Despite our data showing the vast majority of wage claims remain unresolved,

workers have been organizing to fight back. The original AFWA survey showed

one in five workers were part of mutual aid programs for food and rent

coordinated by their trade unions during COVID. Now unions’ efforts are

focused on legal claims, challenging non-payment of wages during COVID.

Their resistance has been especially powerful given anti-union retaliation

against workers during COVID at several of Big Fashion’s supply chain factories.

Table 3: Revisited COVID wage claims as of 2022

Surveyed

Factories

(2020)

4

COVID wage claims at 2020

surveyed factories (USD)

Reviewed

factories

COVID wage claims at

2022 reviewed

factories still unpaid

(USD)

Bangladesh

21

$455,000

0

NA

Cambodia

20

$12.7 million

5

$5 million

India

33

$65.3 million

10

$37.1 million

Indonesia

22

$11.3 million

8

$2.9 million

Pakistan

40

$65.1 million

15

$20 million

Sri Lanka

9

$9.2 million

3

$6.5 million

TOTAL

124 factories

$164 million

41

$71.1 million

4

From original raw data from Money Heist, on file with authors. Table reflects factories verified via

Open Supply Hub and companies’ own public factory lists, among total 189 factories surveyed.

Big Fashion and Wall Street Cash In on Wage Theft

6

But while unions have made important progress factory-by-factory fighting

uphill against fashion goliaths’ suppliers, the unresolved claims show that the

scope of wage losses can only be addressed by the fashion companies at the

top of these supply chains. AFWA’s 2020 survey reached a small but significant

sample of the factories supplying major fashion companies in six Asian

countries. Taking data collected as representative of a likely overall trend, the

total potential COVID wage claims for Nike, Levi’s and North Face parent

company VF Corporation in just the six surveyed countries could be hundreds

of millions of dollars. This estimate, based on the total number of factories in

each company’s supply chain as shown in Table 4, represents life-changing pay

cuts for hundreds of thousands of low-income garment workers and their

families.

Table 4: COVID wage claims by fashion company

No. surveyed

factories (2020)

in supply chain

COVID wage claims at

surveyed factories

(2020) (USD)

Ave. wage claims per

factory in supply

chain in six countries

(USD)

No. company

reported factories

in surveyed

countries

5

Levi’s

8

$12.2 million

$1.25 million

156

Nike

9

$9.3 million

$1.03 million

93

VF

4

$2.5 million

$625,000

218

Big Fashion companies can pay these wage claims back, having made an

incredible, profitable recovery. By March 2022, Levi’s, the world’s largest jeans

company, had its highest revenues in over two decades. In December 2020, VF

Corporation spent $2.1 billion on acquiring viral streetwear brand Supreme.

Despite ongoing challenges in the sector, many companies have come out

stronger from the COVID pandemic. As Nike’s CEO said to investors in

September 2020, “We can thrive in this environment.” Nike may have thrived,

but the data shows garment workers did not.

WORKERS SPEAK OUT

The financial crisis for Big Fashion’s garment workers in the Global South did

not begin in 2020. Supply chain factories have paid sub-poverty and even

subminimum wages for generations. And while brands like Nike, VF and Levi’s

may not count these workers as employees, their cheap labor produces Big

Fashion’s clothing and profits.

Garment workers spend long hours in factories cutting, spinning and sewing

under the enormous pressure of production quotas, just to earn the wages that

5

See supplier lists for Levi’s, Nike, and VF.

Big Fashion and Wall Street Cash In on Wage Theft

7

they need to live — and when they are cheated out of fair pay, the impacts are

devastating for them and for their families.

Netra and Diah, working in Nike’s supply chain in Indonesia

Netra

6

has worked for five years in an Indonesian factory where she sews more

than two thousand pieces of Nike apparel each day and earns a monthly salary

of roughly $270 USD. Like many of her coworkers, Netra migrated from a small

village in central Java to the capital Jakarta, where she moved in with her aunt

and found work in one of hundreds of garment factories in the area. At first,

Netra began to earn enough to send home and support her mother and two

older siblings. Her family made plans to add a room to their home so not all

family members would have to sleep together.

Then the pandemic began, and Netra’s factory rotated workers in two-week

periods to reduce personnel as fashion companies cut their orders. She earned

roughly half of her usual monthly income from April through August of 2020.

Even when her hours returned to normal, pay came late for months more. The

plans to fix the family home came to a halt, and Netra struggled to send

enough back just to keep her brother in school. Netra’s meager savings

evaporated, and more than two years later she has not been able to build it

back.

Diah, introduced at the beginning of this report, who works at the same

Indonesian Nike-sourcing factory, stamps the famous “swoosh” logo onto pairs

of gloves. She recalls how her family’s eating habits changed as her income was

slashed toward the beginning of the pandemic. They cut meat, chicken and fish

from their diet and could only afford vegetables and eggs. Before COVID, Diah

had managed to send a full half of her salary to her hometown to support her

parents. She did everything she could to continue that support, keeping only

what she needed for food and transportation to and from the factory. Diah had

dreamed of saving up to eventually open a small coffee shop, but her savings

disappeared completely in 2020.

Netra and Diah agreed that the employer ignored workers’ needs throughout

the pandemic, offering nothing but hand sanitizer and temperature checks.

Workers also had to buy their own face masks. When she felt ill, Diah was

desperate not to look pale and to avoid coughing at work, terrified she would

be forced to take a swab test – tests that the factory required but that workers

had to pay for themselves. One test would have cost Diah half of her monthly

salary in those most difficult months of 2020.

Netra and Diah have common stories as women workers and internal migrants

who try to use low garment factory wages to cover their own and distant

6

Netra’s name has been anonymized to protect against retaliation. She is a member of an

AFWA-affiliated union in Indonesia.

Big Fashion and Wall Street Cash In on Wage Theft

8

families’ necessities. They both describe stretching low wages to get by when

pay and working hours were “normal,” but sinking into financial crisis as soon as

the pandemic interrupted normal operations – a crisis from which they have not

recovered nearly three years later.

Arham, working in Levi’s supply chain in Pakistan

In Lahore, Pakistan, Arham

7

has worked for seven years as an assistant

supervisor in a factory that supplies Levi Strauss & Co. Before the pandemic, his

salary was just barely enough to support his family of seven, especially as his

daily commute cost a full 20% of his paycheck. However, he was pleased to be

able to pay to put his children in private schools.

When the pandemic began, and the government imposed a two-month

lockdown, half of Arham’s coworkers were laid off without pay while the other

half remained at the factory. The bonuses that made up a significant part of

workers’ regular income, and money from a “workers profit participation fund,”

disappeared for those who kept working. Arham borrowed money and had

trouble providing meals to his family. Even after the lockdowns ended and the

Pakistani government offered tax relief to the garment industry, Arham’s

factory cited decreased orders to cut salaries in December 2020 by 20-25%,

making the crisis permanent for workers.

More than two years later, Arham and his family remain in debt. They have

adjusted their lives to accommodate the decreased income, including moving

their children out of their private schools.

Dilhani, working in Nike’s supply chain in Sri Lanka

In Sri Lanka, Dilhani worked for six years in a factory that sources Nike, piecing

together enough income together with her husband to care for their three

children. COVID did not slow down Dilhani’s factory – the orders continued and

production targets increased at the same time that more people missed work

due to the pandemic. Even as they worked harder than before, Dilhani and her

coworkers found their pay reduced. One month they only received half of their

salaries. They were not paid for many hours of forced overtime. Meanwhile,

food became scarce and more expensive.

As a representative on the factory’s employee council, Dilhani had always been

one of the voices who spoke up about workplace issues. And she did so again in

2020 and 2021, advocating repeatedly for repayment of the subminimum

wages and unpaid overtime. Instead of listening to her demands, the company

called Dilhani into a room in August of 2021. They showed her a resignation

letter to sign and refused to let her leave. They held her for four hours, denying

her access to her belongings or a washroom. In the end, she agreed to sign.

Since this incident, Dilhani has fallen into a cycle of debt and sells fruit by the

7

Arham’s name has been anonymized to protect against retaliation. He is a member of an

AFWA-affiliated union in Pakistan.

Big Fashion and Wall Street Cash In on Wage Theft

9

roadside to try to make ends meet as she pursues her case for justice at the

factory.

These four workers are just a tiny sample of the millions of garment workers in

the region whose financial stability collapsed due to pandemic wage theft and

wage losses. Worse yet, by the beginning of 2023, none of these workers had

recovered. The Big Fashion companies that profit from their labor, on the other

hand, have recovered and thrived – but they have chosen not to address the

massive claims of these workers, instead helping their wealthiest investors

amass larger and larger fortunes.

AT PEAK CRISIS, BIG FASHION COMPANIES GIVE BILLIONAIRES

WINDFALL WHILE ABANDONING WORKERS

In April and May 2020, as millions of garment workers in Big Fashion supply

chains were locked down and being laid off or fired en masse, Big Fashion gave

its billionaire owners a windfall — while workers got nothing. As shown in Table

5, March 2020 alone the Barbey family, owner of VF Corporation, raked in $32.4

million in dividends. In April 2020 alone the Haas family, owner of Levi’s, paid

themselves $19.7 million in dividends. In March and May 2020, the Knight

family, which controls Nike, paid themselves $74 million in dividends, as

mentioned in the introduction of this report.

Table 5: Fashion billionaire dividends, Spring 2020

Family

Total shares as of

Spring 2020

Dividend

Total payout,

Spring 2020

Levi’s

Haas family

8

246,628,690

9

$.08 per share in April 2020

$19,730,295

Nike

Knight family

10

151,207,399

11

$.245 per share in March

and May 2020 ($.49 total)

$74,091,265

VF

Barbey family

12

67,529,185

13

$0.48 per share in March

2020

$32,414,008

Big Fashion profits a few dynastic families like these that have inherited wealth

for decades or centuries since the corporate founding of their family’s

8

Members holding Class B stock and more than 5% of total shares, who are: Mimi Haas,

Margaret Haas, Robert Haas, Peter Haas Jr., Peter Haas Jr. Family Fund, Daniel Haas,

Jennifer Haas. Members and stock holdings as of February 14, 2020.

9

Total shares held by the Haas family as per above, as of February 14, 2020.

10

Phillip K. Knight and Travis A. Knight 2009 Irrevocable Trust II.

11

Held by Knight family as of May 31, 2020.

12

Barbey Family Trust and Todd Barbey.

13

Barbey Family Trust held 39,670,165 and Todd Barbey held 27,859,020 shares as of May

29, 2020.

Big Fashion and Wall Street Cash In on Wage Theft

10

company. The billionaire Haas family has been living off inherited wealth for

over 150 years from Levi Strauss & Co, which they control. The Knight family,

which has owned Nike since Phil Knight founded the company fifty years ago, is

worth $45 billion, making them the 25th wealthiest family in the world. The

$7.3 billion dollar Barbey family is the 50th wealthiest family in America at time

of writing from over a century of inherited wealth from the founding of what is

now VF Corporation.

The payouts during the worst moment of pandemic lockdowns in Spring 2020

are only the beginning of the story of Big Fashion companies creating windfalls

for ownership families and wealthy investors while neglecting workers. In

October 2020, Mimi Haas cashed in a chunk of her Levi’s stock for $7.8 million.

In the first year of the pandemic, Phil Knight’s net worth increased $20.4 billion.

In Fiscal Year 2020 and 2021, Nike spent a total of $3.1 billion on dividends,

which would have returned several million more back to the Knight family.

These families have spent their pandemic windfalls to further enrich

themselves. In 2022, Levi’s Mimi Haas spent $100,000 to defeat a proposal that

would mitigate climate change but raise her taxes. In 2021, Levi’s heir Daniel

Lurie (stepson of Mimi Haas) bought a $15 million dollar house in San Francisco.

Nike’s Phil Knight spent over $7 million to unsuccessfully influence the Oregon

governor’s race towards a pro-corporate candidate. The Barbey Family’s widely

publicized and influential donations of $20 million through their charitable

trust was a fraction of what they earned during the pandemic through

dividends, while workers in VF’s supply chain waited to be paid for hours they

worked making VF products.

SINCE PANDEMIC, BIG FASHION COMMITS BILLIONS TO SHARE

BUYBACKS FOR WALL STREET

Wall Street also cashed out on their holdings of Big Fashion during COVID

through share buybacks.

Share buybacks contribute to an economy that works for Wall Street instead of

working people. Corporations use stock buybacks to inflate their share prices,

making millions for shareholders by repurchasing their own stock, cutting the

number of shares that represent the total value of the company and therefore

making each share worth more. Wall Street benefits from buybacks in large

part because big Wall Street firms Blackrock, State Street and Vanguard —

known as the Big Three— have a controlling stake in companies and drive

buybacks. The substantial corporate profits of Big Fashion could be used as

reinvestment, including for increased production or living wages for workers

throughout supply chains. Instead, corporations are extracting wealth from

companies and from their workers to create shareholder value for the already

Big Fashion and Wall Street Cash In on Wage Theft

11

powerful and wealthy: an increasingly consolidated group of dominant

investors.

While most Big Fashion companies temporarily paused their buybacks in 2020,

Nike and Levi’s not only restarted but increased their share buyback programs

by 2022. Nike authorized a new $18 billion dollar buyback program ($3 billion

more than before), Levi’s approved a $750 million share repurchase program

($650 million more than before). VF Corporation reinstated its existing share

buyback program in 2021, and projects spending $7 billion on share

repurchases and dividends in the next four years. Big Three Wall Street firms

own an average of 15% of these companies and a comparable percentage of

much of the industry.

We compared Big Fashion’s current share buyback authorizations to COVID

wage claims in their supply chains. With their current share buybacks

authorizations, Big Fashion companies can pay back the workers in the

factories that AFWA surveyed on average more than a thousand times over. As

a particularly extreme example, Nike could pay back workers in these factories

almost two thousand times.

Garment workers are among workers around the world who are fighting back

against buybacks that keep them from getting a fair share and decent wages. In

the United States, fast food workers, coal miners, airline workers and retail

workers are taking on major corporations including McDonalds and Walmart to

demand an end to buybacks. Airline workers are demanding airlines — who

have ongoing operational crises and unmet worker demands — commit to “No

Stock Buybacks” moving forward, after the US government required a pause on

buybacks as a condition of COVID relief, thanks in part to pressure from labor.

Workers at Warrior Met Coal who have been on strike for over a year are

challenging buybacks by the company that have enriched its largest

shareholder Blackrock. Studies show that if McDonald’s and Starbucks had

redirected the money they spent on buybacks to workers instead, they could

have paid their several million workers $4,000 more and $7,000 more,

respectively.

Nike, Levi’s, and VF Corporation all celebrated spending billions on Wall Street,

describing share repurchases as a recognition of generating “shareholder

value” — but what about the workers who make any value possible? While

billionaire families and their Wall Street allies raked in millions during COVID, is

anyone in Big Fashion making sure workers and their families stayed afloat?

Big Fashion and Wall Street Cash In on Wage Theft

12

WORKERS VS. BIG FASHION: FIGHTING BACK

The data from AFWA’s Money Heist report and its most recent revisiting of

factories, together with the high levels of dividends and stock buybacks since

the beginning of the COVID pandemic, tell a clear and infuriating story. Big

Fashion companies like Nike, Levi’s and VF used the COVID-19 pandemic to

facilitate an enormous extraction of wealth from hundreds of thousands of

low-wage Asian garment workers to a few of the world’s richest fashion heirs

and investment firms.

Workers who create the clothing and fortunes of Big Fashion’s most

recognizable brands deserve living wages and clear protections to assure that

they are not fleeced again in future global crises. For that reason, workers are

coming together across borders and employers to demand direct bargaining

with Big Fashion companies. They are demanding systemic investigations of all

COVID wage claims, an end to billionaire payouts from dividends and stock

buybacks until all garment workers are repaid their lost wages, and a new

partnership between garment worker unions and fashion companies to create

fair supply chains with living wages.

Big Fashion and Wall Street Cash In on Wage Theft

13

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Asia Floor Wage Alliance (AFWA) The Asia Floor Wage Alliance (AFWA) is an

Asian labor-led global labor and social alliance across garment-producing

countries in Asia and consumer regions of USA and Europe. Founded in 2007,

AFWA aims to build regional unity among Asian garment unions to overcome

the limitations of country-based struggles in global production networks and

holds global fashion brands accountable. AFWA’s historic cross-border living

wage formulation for Asian garment workers is also the only women-centered

formulation of its kind. For more information, please contact AFWA at

Global Labor Justice – International Labor Rights Forum (GLJ – ILRF) is a

new merged organization bringing strategic capacity to cross-sectoral work on

global value chains and labor migration corridors. GLJ-ILRF holds global

corporations accountable for labor rights violations in their supply chains;

advances policies and laws that protect decent work and just migration; and

strengthens freedom of association, new forms of bargaining, and worker

organizations. For more information, please contact Noah Dobin-Bernstein,

GLJ-ILRF at [email protected].

Copyright © 2023

Global Labor Justice - International Labor Rights Forum (GLJ-ILRF)

Asia Floor Wage Alliance (AFWA)

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-

NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. You are free to copy and redistribute

the material in any medium or format pursuant to the following conditions. (1)

Attribution: You must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and

indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but

not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use. (2) Non-

Commercial: You may not use the material for commercial purposes. (3) No

Derivatives: If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you may not

distribute the modified material. To view a complete copy of the license,

visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode.