Ideal crop marks

Dedicated to the World’s Most Important Resource

®

Get the full report at

www.awwa.org/solutions

2015

AWWA State of the

WATER INDUSTRY

Report

2

© 2015 American Water Works Association

2015 AWWA State of the Water Industry Report

Established in 1881, the American

Water Works Association (AWWA) is

the largest nonprofi t, scientifi c, and

educational association dedicated to

providing solutions to manage the

world’s most important resource—

water. With approximately 50,000

members and 5,000 volunteers, AWWA

provides solutions to improve public

health, protect the environment,

strengthen the econom y, and enhance

our quality of life.

CONTENTS

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3

PART 1—PURPOSE AND

METHODOLOGY . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5

Purpose. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5

Methodology . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5

PART 2—STATE OF THE

WATER INDUSTRY . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10

Background . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10

State of the Water Industry . . . . . . 15

PART 3—ISSUES . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 21

System Stewardship . . . . . . . . . . . . 24

Water Resources Management . . . 32

Value of Water (Resources/

Systems and Services). . . . . . . . . . . 41

Regulations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 43

Workforce Issues . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 46

Other Issues . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 48

PART 4—CONCLUSIONS. . . . . . . . . . . 51

REFERENCES . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 52

APPENDIX A—2015 State of the

Water Industry Survey . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 54

APPENDIX B—2015 SOTWI Survey

Responses by Location . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 60

APPENDIX C—2015 Health of

the Industry Responses by Location . . . 62

© 2015 American Water Works Association

3

2015 AWWA State of the Water Industry Report

Executive Summary

AWWA has been formally tracking issues and

trends in the water industry since 2004 through

the State of the Water Industry (SOTWI) study.

AWWA continues to conduct this annual sur-

vey in order to:

Identify and track significant challenges

facing the water industry

Provide data and analysis to support water

professionals as they develop and commu-

nicate strategies to address current issues

Discover and highlight potential problems

or concerns on the water industry’s horizon

Inform decision makers and the public of

the challenges faced by the industry

In September 2014, emails were randomly sent

to a general list of AWWA members and con-

tacts inviting participation in the 2015 SOTWI

survey. A total of 1,747 respondents completed

a majority of the survey. Because the amount of

self-selection bias is unknown, no estimates of

error have been calculated.

Some of the major findings of this study are:

The current health of the industry as rated

by all respondents was 4.5 on a scale of 1 to

7, down slightly from the 2014 score of 4.6;

this score has fallen into a range of 4.5 to 4.9

since the survey began in 2004.

In looking forward five years, the sound-

ness of the water industry was expect-

ed to decline to 4.4 from the 2014 score of

4.5 (again out of 7.0); this score has fallen

into a range of 4.4 to 5.0 since the survey’s

inception.

The top five most important issues were

identified as follows:

1. Renewal and replacement (R&R) of aging

water and wastewater infrastructure

2. Financing for capital improvements

3. Long-term water supply availability

4. Public understanding of the value of

water systems and services

5. Public understanding of the value of

water resources

There is a gap between the financial needs

of water and wastewater systems and the

means to pay for these services through

rates and fees. Nine percent of all respon-

dents felt that water and wastewater utili-

ties are not at all able to cover the full cost of

providing service, including infrastructure

R&R and expansion needs, through cus-

tomer rates and fees. More striking, sixteen

percent of all respondents are concerned

that utilities will not be able to cover the

full cost of providing service in the future.

Thirty percent of utility employees re-

sponded that their utilities are currently

struggling to implement full-cost pricing,

up from 28 percent in 2014. In addition,

38 percent of respondents think they will

struggle to cover the full cost of service in

the future, up from 35 percent in 2014.

Concerning infrastructure R&R, the most

important issue was establishing and fol-

lowing a financial policy for capital rein-

vestment. Other critical concerns in this

area are prioritizing R&R needs and jus-

tifying R&R programs to ratepayers and

oversight bodies (board, council, etc.)

Forty three percent of utility respondents

reported declining total water sales (ei-

ther a >10 year or <10 year trend) while

29 percent of respondents reported their

total water sales were flat or little changed

in the last 10 years. In all, this means that

three-quarters of utilities are facing the is-

sues associated with low or declining water

demand that can dramatically impact cost

recovery, i.e., pricing water to accurately re-

flect its true cost.

The most reported cost recovery strategies

from utility employees were (1)shifting more

4

© 2015 American Water Works Association

2015 AWWA State of the Water Industry Report

of the cost recovery from consumption-based

fees to fixed fees within the rate structure,

(2)changes in growth- related fees, (3) shift-

ing rate design to increasing block-rate struc-

ture, and (4)increasing financial reserves.

When asked “How prepared do you think

your utility will be to meet its long-term

water supply needs,” 11 percent of utili-

ty personnel indicated their utility will be

challenged to meet anticipated long-term

water supply needs, up from 10 percent in

2014.

Regarding management of groundwater re-

sources, the most important issues identified

through the SOTWI Survey were (1) de-

clining groundwater levels, (2) watershed/

groundwater protection, and (3) ground-

water regulations.

Seventy two percent of respondents felt the

general public has a poor or very poor un-

derstanding of water systems and services

(up from 70 percent in 2014), and 61 percent

felt the general public has a poor or very

poor understanding of water resources (up

from 59 percent in 2014). Similarly, 66 per-

cent of respondents felt residential custom-

ers have a poor or very poor understanding

of water systems and services up (up from

65 percent in 2014), while 59 percent felt the

general public has a poor or very poor un-

derstanding of water resources (up from

56percent in 2014).

The top three current regulatory con-

cerns were identified as (1) chemical spills,

(2)point source pollution, and (3) combined

sewer overflows.

The 2015 SOTWI report provides specific guid-

ance on where the industry feels investments

are most needed and where action would be

most beneficial. Water professionals must work

collectively to develop sound and sustainable

solutions to the issues identified in this report

and to then disseminate and implement them

at the local and regional levels where water-

related decisions are mostly made. Public input

and proactive community involvement are

essential to the success of this process.

AWWA provides a forum for innovation and

leadership in the water industry by not only

identifying and tracking important water issues

but also by focusing the efforts and contribu-

tions of its dedicated volunteers and members

to develop information and guidance to protect

the world’s most important resource—water.

© 2015 American Water Works Association

5

2015 AWWA State of the Water Industry Report

Part 1—Purpose and Methodology

Purpose

AWWA supports the water industry by provid-

ing solutions to effectively manage the world’s

most important resource—water. AWWA first

developed the SOTWI survey and report in

2004 to

Identify and track significant challenges

facing the water industry

Provide data and analysis to support water

professionals as they develop and commu-

nicate strategies to address current issues

Discover and highlight potential problems

or concerns on the water industry’s horizon

Inform decision makers and the public of

the challenges faced by the industry

AWWA’s annual SOTWI survey encourages

reflection on the water industry’s current and

future challenges and priorities, allowing

participants to serve as a voice for their col-

leagues. This industry-wide self-assessment

provides information to support many of the

water community’s common values including

safeguarding public health, supporting and

strengthening communities, and protecting the

environment. Figure 1 highlights these values

and how they are realized.

Methodology

The SOTWI survey population includes all

water professionals, i.e., those with an under-

standing and appreciation of the issues facing

the entire water industry. The SOTWI survey

classifies participants based on which of the

following categories best describes the type of

organization they work:

Drinking water utility

Wastewater utility

Combined water/wastewater utility (may

include other services too)

Water wholesaler reuse/reclamation utility

Stormwater utility

Consulting firm/consultant

Manufacturer of products

Manufacturer’s representative

Distributor

Technical services/contractor

Regulatory authority/regulator

Nonutility government (municipal,

federal, etc.)

University/educational institution

Laboratory

Financial industry (ratings agency, investor/

fund rep., etc.)

Law firm/attorney

Nonprofit organization

Retired

Other

Safeguard Public Health

• Safe drinking water

• Fire protection

• Water pollution control

Support and Strengthen Communities

• Adequate and reliable supplies

• Appropriate water quality

• Appropriate prices (nancial sustainability)

Protect the Environment

• Adequate and reliable supplies

• Appropriate water quality

• Efcient use of supplies for minimum

impacts (environmental sustainability)

Figure 1. Water Industry Values

6

© 2015 American Water Works Association

2015 AWWA State of the Water Industry Report

Throughout the SOTWI study, AWWA made

deliberate efforts to anticipate and minimize

errors due to coverage, sampling, nonresponse,

and measurement. Coverage errors can result

when members of the survey population have

an unknown nonzero chance of being included

in the sample. Sampling errors can result if data

is collected from only a subset instead of all

members of the sampling frame, which is the

list from which a sample is to be drawn in order

to represent the survey population. The 2015

SOTWI sample frame consisted of a general

list of AWWA members and contacts. Because

the bulk of AWWA members reside in North

America, the survey primarily reflects water

industry concerns in the United States, Canada,

and Mexico.

A survey sample consists of all units of a popu-

lation that are drawn from the sample frame for

inclusion in the survey. To minimize coverage

errors, the sample for the 2015 SOTWI Survey

was distributed with the goal to provide uni-

form response from states and provinces. Indi-

viduals from the categories in the following

list were randomly selected from AWWA’s full

contact list using a generic randomization func-

tion, and the survey was sent to them via email.

To avoid bias, AWWA membership was not

considered in the survey distribution, meaning

it was sent to members and nonmembers alike.

1. All North American utilities (water,

wastewater, combined, etc.)

2. All North American service providers

3. All North American partner agencies

and institutions

4. All Canadian individual members

5. All Mexican individual members

6. All International individual members

7. U.S. individual members as by state with

the goal of producing uniform response

rate by state population

In September, 2014 initial email invitations

were sent to 99,354 randomly selected email

addresses, based on the criteria previously

described. On Sept. 23, 2014, a follow-up email

was sent to this same group. After removing

wholly incomplete responses (i.e., surveys sub-

mitted with no responses at all), the total num-

ber of respondents responding to the 2015

SOTWI survey was 1,747. See Appendix A for

the full 2015 SOTWI survey and Appendix B

for a summary of the location specific response

rates.

The data have not been weighted to reflect the

demographic composition of any target popu-

lation. Because the population size (i.e., water

professionals in North America) is not well-

defined and the amount of self-selection bias

is unknown, no estimates of error have been

calculated. For figures summarizing multiple

survey responses, the number of respondents

(n) as reported or shown in headings reflects

the question that returned the lowest number

of respondents of all the questions asked.

Figure 2 shows the total number of respondents

based on their designated current career; all

categories received responses. Approximately

53 percent of respondents (922) indicated they

worked for a utility, while 47 percent (817) were

not directly employed by a utility. The top 5

total responses by career type are as follows:

1. Combined water/wastewater utility:

29% (501)

2. Drinking water utility: 22% (386)

3. Consultant/consulting firm: 18% (312)

4. Government/regulatory agency: 5% (89)

5. Manufacturer of products: 5% (83)

© 2015 American Water Works Association

7

2015 AWWA State of the Water Industry Report

Figure 2. Number of respondents for the 2015 SOTWI survey by career category (n = 1,747)

Figure 3 shows the age distribution of the

2015 SOTWI survey respondents. The largest

response was from the age range 55–64 (30 per-

cent) while the smallest was the age range <25

(2 percent). The age distribution of respondents

was slightly skewed to those who have likely

been water professionals for a longer period of

time, but overall there was reasonable represen-

tation in all age range categories.

The Water Industry Sector. Industry. Community. Profession. These terms

are commonly used interchangeably, but which is the most appropriate?

From an economic perspective, Sectors are top-level descriptors that

divide an economy into a broadly similar functions such as finance and

insurance, manufacturing, construction, or utilities. Within each economic

sector, there is further segmentation into industries. For example, within

the utilities sector, there are electric utilities, gas utilities, and water utili-

ties. Professionals working in the water industry ensure the safe and reli-

able delivery of water, wastewater, reuse, and stormwater services. These

water professionals form a community of leaders that generally shares the

same values of safeguarding public health, supporting and strengthening

communities, and protecting the environment as described in Figure 1.

8

© 2015 American Water Works Association

2015 AWWA State of the Water Industry Report

Figure 3. Number of respondents for the 2015 SOTWI survey by Age (n=1,746)

Figure 4 provides an overview of the number of

water service connections or collection system

connections served by the utility-career partic-

ipants, of which there were 678 total responses.

Those responding for combined systems were

instructed to use the larger between their sys-

tems’ water and wastewater connections. The

population served by a water or wastewater

system can be estimated by multiplying the

number of connections by 3.5, i.e., there are

approximately 3.5 people are served for each

connection.

Utility personnel consist of the following career

categories:

Water utility

Wastewater utility

Combined water/wastewater utility

Water wholesaler

Reuse/reclamation utility

Stormwater utility

The largest group of utility respondents served

more than 150,000 connections (meaning popu-

lations greater than approximately 500,000 peo-

ple), while the smallest number of respondents

served between 100,001 to 150,000 connections.

For this survey, small utilities are those that

serve 3,000 or less connections (service popula-

tions of less than approximately 10,000 people).

Ninety percent of the utility personnel who

responded worked for public utilities, while

10percent worked for private utilities.

© 2015 American Water Works Association

9

2015 AWWA State of the Water Industry Report

Figure 4. Summary of 2015 SOTWI respondents working for a utility by the number of service

connections their utility serves (n= 678)

Any others industry challenges rating at least “very important” but not listed (please

specify):

• Access to external government funding (for small systems in Canada), affordable

insurance, bulk purchasing initiatives, and affordable debt financing.

• Concern that increasingly stringent MCLs (for THMs, for example) will unneces-

sarily elevate costs (and rates).

• Infrastructure condition assessment and remaining life determination.

• We cannot under estimate the effects of drought and the importance of year-

round conservation. We must diversify our industry and attract new workers to

replace retiring ones. We are already competing with the oil & gas industry who

typically pay more than we do.

Excerpt from open-ended questions

10

© 2015 American Water Works Association

2015 AWWA State of the Water Industry Report

Part 2—State of the Water Industry

Background

The results of the 2015 SOTWI survey are bet-

ter understood against the backdrop of the

“waterscape” in North America. As the report

is published, the populations of the Canada,

Mexico, and the United States continue to grow

as shown in Figure 5 although the growth rate

has been leveling off in recent years. For a view

of the current North American population den-

sity, see Figure 6.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency

(USEPA) provides drinking water system infor-

mation through the federal version of its Safe

Drinking Water Information System. Table 1

provides the number of U.S. community water

systems in 2014 based on the size of the service

population. A community water system pro-

vides water for human consumption through

pipes or other constructed conveyances to at

least 15 service connections or serves an aver-

age of at least 25 people year-round.

Figure 5. Populations (in millions) in North America by Year (created from Google Public Data,

http://www.census.gov/popclock/, http://www.statcan.gc.ca/daily-quotidien/140926/

dq140926b-eng.htm?HPA, and http://www.statista.com/statistics/263748/total-

population-of-mexico/ —accessed 12/12/14)

© 2015 American Water Works Association

11

2015 AWWA State of the Water Industry Report

Table 1. U.S. community water system summary (USEPA 2015)

System

Service

Population

Very

Small

<=500

Small

501–3,300

Medium

3,301–

10,000

Large

10,001–

100,000

Very Large

>100,000 Total

Number of

Systems

28,595 13,727 4,936 3,851 426 51,535

% Total

Systems

55 27 10 7 0.8 100

Service

Population

4,738,080 19,688,745 28,758,366 109,769,304 137,250,793 300,205,288

% Total

Population

1.6 6.6 10 37 45.7 100

People/

System

166 1,434 5,826 28,504 322,185 5,825

Figure 6. North American population density (Britannica Online for Kids

2015)

12

© 2015 American Water Works Association

2015 AWWA State of the Water Industry Report

As shown in Figure 7, the total number of com-

munity water systems has decreased over the

last four years by 1,338 or 2.5 percent over this

time period. This change reflects an overall

decrease in the number of smaller systems (Very

Small and Small, see Table 1 for definitions) and

an increase in the number of larger systems

(Large and Very Large). These changes gener-

ally support the understanding that urbaniza-

tion and regionalization are increasing.

In late 2014 the United States Geological Survey

released its summary of water use in the United

States through Circular 1405: Estimated Use of

Water in the United States in 2010 (USGS2014).

Figure 8 shows the amount of water with-

drawals across the U.S. from 1950 to 2010. It is

interesting to note that water use in the United

States in 2010 was 13 percent less than in 2005

and was at the lowest level since before 1970.

Most of this decrease occurred because of lower

fresh surface water withdrawals. Of the water

withdrawals in 2010 (355 billion gallons/day or

BGD), approximately 12 percent was used for

public supply (42 BGD); 32 percent was used for

irrigation (115 BGD); and 45 percent was used

for thermoelectric power (161 BGD). Also the

USGS report stated that the average domestic

per capita water use in 2010 was reported to be

88 gallons/day.

Figure 7. Number of community water systems by year (USEPA 2015)

© 2015 American Water Works Association

13

2015 AWWA State of the Water Industry Report

Figure 8. Water withdrawals in the United States 1950-2010, (USGS 2014)

USEPA tracks the number of operational waste-

water treatment facilities every four years

through its Clean Watersheds Needs Survey

(CWNS). The most recent data available as pub-

lished in 2008 is shown in Table 2, which pro-

vides a summary of the number of wastewater

treatment facilities by flow. USEPA is expected

to deliver the CWNS 2012 Report to Congress

and provides data to the public via the USEPA

website in early 2015.

Statistics Canada provides Canadian system

information through its Human Activity and

the Environment data tracking efforts. Table 3

provides a summary of drinking and waste-

water plants in Canada for public facilities serv-

ing communities of 300 or more people. This

summary does not include federal systems or

facilities administered by Indian and North-

ern Affairs Canada. Table 4 presents the pop-

ulations in Canadian provinces and territories

served by various source waters.

14

© 2015 American Water Works Association

2015 AWWA State of the Water Industry Report

Table 2. U.S. wastewater system summary (USEPA 2008)

1

Existing flow range

(MGD)

Number of

facilities

Total existing

flow (MGD)

Present design

capacity (MGD)

0.000 to 0.100 5,703 257 490

0.101 to 1.000 5,863 2,150 3,685

1.001 to 10.000 2,690 8,538 13,082

10.001 to 100.000 480 12,847 17,267

100.001 and greater 38 8,553 10,344

Other

2

6 - -

TOTAL 14,780 32,345 44,868

1

Alaska, North Dakota, Rhode Island, American Samoa, and the Virgin Islands did not participate in the CWNS 2008

2

Other—Flow data for these facilities were unavailable

Table 3. Canadian drinking water and wastewater system summary (Statistics Canada 2009)

Population served

Number of

drinking water

plants

Number of

sewage treat-

ment plants

300to500 364 390

501to5,000 1,226 1,272

5,001to50,000 337 366

More than50,000 91 85

Total 2,018 2,113

© 2015 American Water Works Association

15

2015 AWWA State of the Water Industry Report

Table 4. Canadian population served by drinking water plants for various water sources

(Statistics Canada 2009)

Provinces and Territories

Population Served by Water Source

Surface

water Groundwater

Groundwater under

the direct influence

of surface water Total

Newfoundland and Labrador 379,755 28,096 — 412,091

Prince Edward Island 0 63,807 0 63,807

Nova Scotia 500,351 71,370 4,500 576,221

New Brunswick 224,393 140,923 15,604 380,920

Quebec 6,165,044 935,925 83,763 7,184,732

Ontario 9,708,702 1,288,678 234,390 11,231,770

Manitoba 841,893 110,680 13,754 966,327

Saskatchewan 658,470 139,162 10,155 807,787

Alberta 3,093,062 98,341 47,322 3,238,725

British Columbia 3,500,600 449,046 25,413 3,975,059

Yukon - 27,096 3,500 30,596

Northwest Territories 40,511 - 0 40,511

Nunavut - - - -

Canada (TOTAL) 25,149,570 3,353,524 442,641 28,945,736

Documentation of the number of Mexican water

and wastewater systems and water use was not

available at the time this report was written.

State of the Water Industry

As has been done since the beginning of the

SOTWI survey, the 2015 version asked partici-

pants for their opinion of the current and future

health of the water industry by responding to

the following questions using a scale of 1 to 7

where 1 = not at all sound and 7 = very sound.

In your opinion, what is the current overall state

of the water industry?

Looking forward, how sound will the overall

water industry be five years from now?

Figure 9 shows the average scores to these two

questions from 2004 to present. The current

health of the water industry as rated by all

respondents was 4.5 out of 7.0, down slightly

from the 2014 score of 4.6. However, this score

falls into the range of 4.5 to 4.9, which has been

observed since the beginning of the survey.

Although the minimum error associated with

these responses cannot be estimated, there is

little difference in the water industry health

scores over the last several years. The consis-

tency of these scores suggests that the water

and wastewater industry is resilient in the face

of the local, national, and external crisis that

often impact other sectors and industries.

16

© 2015 American Water Works Association

2015 AWWA State of the Water Industry Report

Figure 9. Health of the water industry – all respondents (rating scale: 1 to 7)

In five years, the soundness of the water indus-

try is expected to decline to 4.4 from the 2014

score of 4.5 out of 7.0. While leaving aside

potential statistical differences, the current and

forward-looking trends reflect respondent atti-

tudes that the soundness of the water industry

is just a little lower than the historical averages

of 4.7 for the current perception and 4.6 for the

future perception.

In 2008 (during the start of the global recession),

the current and forward-looking assessments

of the water industry’s soundness changed so

that the expectation of future soundness was

less than the current state (i.e., things will be

slightly worse or no better in the future).

In addition to asking about the overall state

of the water industry’s soundness, the 2015

SOTWI survey also posed the following ques-

tions to better capture perspectives on regional

soundness, again using a scale of 1 to 7 where

1= not at all sound and 7 = very sound:

In your opinion, what is the current state of the

water industry in the region where you work

most often?

Looking forward, how sound will the water

industry be five years from now in the region

where you work most often?

Figures 10 and 11 show the soundness of the

overall water industry as reported by those

working in the United States and Canada,

respectively. In terms of the current soundness,

both show small decreases over last year, down

to 4.5 from 4.6 for U.S. respondents and down

to 4.6 from 4.7 for Canadian respondents. The

United States also maintains its trend of a rel-

atively pessimistic future outlook (in compar-

ison to the overall sample) with an expected

average soundness score of 4.4 in 2020. In con-

trast, Canadian participants continued their

relatively optimistic outlook for the future with

an average soundness score of 4.7 for 2020.

© 2015 American Water Works Association

17

2015 AWWA State of the Water Industry Report

Figure 10. Health of the water industry – U.S. respondents (rating scale: 1 to 7)

Figure 11. Health of the water industry – Canadian respondents (rating scale: 1 to 7)

18

© 2015 American Water Works Association

2015 AWWA State of the Water Industry Report

As shown in Table 5, the regional soundness

scores were higher in all cases than the over-

all scores by the same groups. The reasons for

this are not immediately apparent, but one

explanation is that people may have a better

understanding of the water and wastewater

systems in the areas where they work while the

water-related news and information from out-

side of their work region is generally negative,

leading to more negative perceptions regarding

the overall industry.

Table 5. Overall and regional perceptions of the water industry soundness for total, U.S., and

Canadian respondents (rating scale: 1 to 7); present (2015) and in 5 years (2020)

Sample

Overall Regional

Counts

2015 2020 2015 2020

All respondents 4.5 4.4 4.6 4.6 1,740

U.S. respondents 4.4 4.3 4.6 4.5 1,530

Canadian respondents 4.6 4.7 5.0 5.0 173

The average scores for the health of the water

industry on a scale of 1 to 7 for the present year

(2015) and five years from now (2020) are pro-

vided in Table 6 for each career category. Few

respondent groups indicated they thought the

health of the industry would be better in five

years, with most expecting a slight decrease

in the soundness of the future water industry.

Leaving aside issues of statistical differences,

the regional soundness scores for most groups

were higher than the corresponding overall

scores, again most likely reflecting the negative

information delivered on a broader scope from

outside the region they understand the best.

The average scores for the water industry’s

health on a scale of 1 to 7 for the present year

(2015) and in five years (2020) are broken out

by respondent age in Table 7. There is little

difference in these scores, with young profes-

sionals (i.e., those in the categories “Younger

than 25” and “25–34”) indicating a slightly more

optimistic outlook for the future. But again, the

somewhat low number of responses may have

led to errors from coverage, sampling, and/or

nonresponse.

Appendix C presents the average scores for the

health of the water industry on a scale of 1 to 7

for the present year (2015) and in five years (2020)

based on the region where participants work

most often. Montana and Georgia returned the

same average scores as all participants (2015 =

4.6, 2020 = 4.5 as shown in Figure7), so those

with higher scores could be considered more

optimistic while those with lower scores could

be considered more pessimistic.

© 2015 American Water Works Association

19

2015 AWWA State of the Water Industry Report

Table 6. Overall and regional soundness of the water industry by career category (scale: 1 to 7);

present (2015) and in 5 years (2020)

Career Category

Overall Regional

Count

2015 2020 2015 2020

Laboratory 4.8 5.2 5.0 5.4 14

Technical services/contractor 4.8 4.7 4.7 4.9 27

Drinking water utility 4.6 4.5 4.8 4.7 383

Water wholesaler

4.6 4.3 4.8 4.4 22

Regulatory authority/regulator

4.6 4.3

4.8 4.6

89

Retired 4.5 4.4 4.4 4.4 28

Combined water/wastewater utility 4.5 4.4 4.7 4.6 500

Law firm/attorney 4.5 4.5 5.0 5.0 2

Nonutility government 4.5 4.4 4.5 4.4 58

Wastewater utility 4.4 4.4 4.2 4.3 32

Distributor 4.4 4.5 4.5 4.5 15

Manufacturer’s representative 4.4 4.5 4.4 4.4 15

University/educational institution 4.4 4.4 4.4 4.4 54

Nonprofit organization 4.4 4.1 4.9 4.8 25

Consulting firm/consultant 4.3 4.2 4.4 4.4 312

Reuse/reclamation utility 4.3 4.3 4.4 5.0 7

Manufacturer of products 4.2 4.5 4.4 4.5 83

Other (please specify) 4.2 4.0 4.3 4.3 69

Financial industry 4.0 4.3 4.7 5.3 3

Stormwater utility 3.7 3.3 3.0 3.3 3

20

© 2015 American Water Works Association

2015 AWWA State of the Water Industry Report

Table 7. Health of the water industry by age category (scale: 1 to 7); present (2015) and

in 5 years (2020)

Age Range 2015 2020 Count

Younger than 25 4.4 5.0 15

25–4 4.6 4.8 204

35–44 4.5 4.4 308

45–54 4.5 4.4 480

55–64 4.6 4.4 518

65 and older 4.6 4.4 144

Prefer not to answer 4.4 4.4 16

Any others rating at least “very concerned” but not listed (please specify):

• Better regulatory protection against large scale unknown contaminant storage

and spills is critically needed.

• Groundwater quality degradation (i.e. salt movement due to overdraft)

• Copper and heavy metals in stormwater runoff will be a big issue in the next

5years

• The issue of wastewater reuse. It should be required in many instances, yet it is

rarely discussed in certain areas of the country.

Excerpt from open-ended questions

© 2015 American Water Works Association

21

2015 AWWA State of the Water Industry Report

Part 3—Issues

To determine the issues that currently impact

the water industry, respondents were asked to

rate the importance of several challenges on a

scale of 1 (unimportant) to 5 (critically import-

ant). These issues, as ranked by 2015 SOTWI

survey respondents, are shown in Table 8. In

addition to the average scores, the percentage of

respondents who scored the issue as critically

important (i.e., 5 on the scale of 1 to 5) is also

presented in Table 8.

Table 8. Issues facing the water industry as ranked by all respondents (n = 1,641)

Rank Category

Score

(1–5)

% Ranked

Critically

Important

1

Renewal and replacement of aging water and wastewater

infrastructure

4.59

64

2 Financing for capital improvements 4.46 57

3 Long-term water supply availability 4.44 58

4 Public understanding of the value of water systems and services 4.37 52

5 Public understanding of the value of water resources 4.28 46

6 Watershed/source water protection 4.21 45

7 Cost recovery (pricing water to accurately reflect its true cost) 4.11 36

8 Emergency preparedness 4.05 33

9 Water conservation/efficiency 4.03 37

10 Compliance with future regulations 4.00 33

11 Groundwater management and overuse 4.00 33

12 Compliance with current regulations 3.98 31

13 Drought or periodic water shortages 3.95 34

14 Asset management 3.94 26

15 Acceptance of future water and wastewater rate increases 3.93 27

16 Water loss control 3.93 25

17 Talent attraction and retention 3.90 27

18 Energy use/efficiency and cost 3.88 20

19 Data management 3.88 26

20 Aging workforce/anticipated retirements 3.87 33

21 Improving customer, constituent, and community relationships 3.81 24

(continued)

22

© 2015 American Water Works Association

2015 AWWA State of the Water Industry Report

Rank Category

Score

(1–5)

% Ranked

Critically

Important

22 Certification and training 3.80 23

23 Expanding water reuse/reclamation 3.79 31

24 Cyber–security issues 3.77 26

25 Physical security issues 3.61 20

26 Wastewater resource recovery 3.56 16

27 Acceptance of current water and wastewater rates 3.55 14

28 Energy recovery/generation 3.51 14

29 Climate risk and resiliency 3.47 19

30 Price and supply of chemicals 3.44 10

31 Stormwater management and costs 3.41 11

32 Fracking/oil and gas activities 3.34 21

33 Affordability for low-income households 3.24 12

34 Workforce diversity 2.91 7

The most important issue to respondents in

2015, renewal and replacement of aging water and

wastewater infrastructure, is the same top issue

from the last several years of surveys (previ-

ously called the state of water and sewer infrastruc-

ture). A comparison of the top ten issues from

2014 and 2015 is presented in Table 9. New to the

top ten in 2015 were water conservation/efficiency

(current #9, prev. #15) and compliance with future

regulations (current #10, prev. #14). Dropping

out of the top ten from 2014 were groundwater

management and overuse (prev. #6, current #11)

and drought or periodic water shortages (prev. #8,

current #13).

Table 10 shows the most important issues

impacting the water industry as ranked by util-

ity and nonutility employees. There were 909

utility employee respondents and 768 nonutil-

ity employee respondents. The first six issues

are the same for both groups.

Table 8. Issues facing the water industry as ranked by all respondents (n = 1,641) (continued)

© 2015 American Water Works Association

23

2015 AWWA State of the Water Industry Report

Table 9. Top 10 issues facing the water industry as ranked by all respondents in 2014 and 2015

Rank 2015 2014

1 Renewal and replacement of aging water and

wastewater infrastructure

State of water and sewer infrastructure

2 Financing for capital improvements Long-term water supply availability

3 Long-term water supply availability Financing for capital improvements

4 Public understanding of the value of water

systems and services

Public understanding of the value of water

resources

5 Public understanding of the value of water

resources

Public understanding of the value of water

systems and services

6 Watershed/source water protection Groundwater management and overuse

7 Cost recovery Watershed protection

8 Emergency preparedness Drought or periodic water shortages

9 Water conservation/efficiency Emergency preparedness

10 Compliance with future regulations Cost recovery

Table 10. Issues facing the water industry as ranked by utility and nonutility respondents

Rank Utility Employees Nonutility Employees

1 Renewal and replacement of aging water and

wastewater infrastructure

Renewal and replacement of aging water and

wastewater infrastructure

2 Financing for capital improvements Financing for capital improvements

3 Long-term water supply availability Long-term water supply availability

4 Public understanding of the value of water

systems and services

Public understanding of the value of water

systems and services

5 Public understanding of the value of water

resources

Public understanding of the value of water

resources

6 Watershed/source water protection Watershed/source water protection

7 Cost recovery (pricing water to accurately

reflect its true cost)

Water conservation/efficiency

8 Emergency preparedness Groundwater management and overuse

9 Compliance with current regulations Cost recovery (pricing water to accurately

reflect its true cost)

10 Compliance with future regulations Drought or periodic water shortages

24

© 2015 American Water Works Association

2015 AWWA State of the Water Industry Report

System Stewardship

Of the top 10 issues facing the water industry

identified in the 2015 SOTWI survey, half of them

including four of the top five pertain to system

stewardship or how water and wastewater sys-

tems are operated, maintained, and replaced.

Renewing and replacing aging infrastructure,

financing for capital improvements, and cost

recovery (i.e., pricing water to accurately reflect

its true cost) are important financial aspects of

system stewardship and have long been a major

concern in the industry. These issues continue

to be important because many water and waste-

water systems built and financed by previous

generations are approaching or have exceeded

their useful lives. Because of past budgeting

approaches that may have included inadequate

revenues to fully cover costs, some municipal

utilities have deferred necessary maintenance

and replacement. Even systems that have acted

as good stewards by planning for the renewal

or replacement of their assets can sometimes

find it difficult to secure reasonable funding for

capital projects and/or to win public support

for these necessary efforts.

AWWA maintains that the public can best be

provided water services by self-sustaining

enterprises that are adequately financed with

rates and charges based on sound accounting,

engineering, financial, and economic princi-

ples. Revenues from service charges, user rates,

and capital charges (e.g., impact fees and sys-

tem development charges) should be sufficient

to enable utilities to provide for the full cost of

service including:

Annual operation and maintenance

expenses

Capital costs (e.g., debt service and other

capital outlays)

Adequate working capital and required

reserves

Full-cost pricing, i.e., charging rates and fees

that reflect the full cost of providing water and/

or wastewater services, should include renewal

and replacement costs for treatment, storage,

distribution, and collection systems. Some util-

ities have previously kept their rates low by

minimizing or ignoring these costs; however, as

the useful lives of their systems draw to a close,

current managers and the communities they

serve are forced to address these costs, some-

times through painful and unexpected rate

increases. Issues related to equity and afford-

ability must be considered as rates are adjusted,

and each system has its own unique rate- setting

challenges based on location and history.

To understand the current state of full-cost

pricing for utilities, all 2015 SOTWI study par-

ticipants were asked “In general, how able are

water and wastewater utilities to currently

cover the full cost of providing service, includ-

ing infrastructure renewal and replacement

and expansion needs, through customer rates

and fees?” To anticipate how circumstances

may change in the future, participants were

also asked the following question: “Given the

future infrastructure needs for system renewal

and replacement and expansion, how able will

water and wastewater utilities be to meet the

full cost of providing service through customer

rates and fees?” The responses to these ques-

tions are shown in Figure 12.

© 2015 American Water Works Association

25

2015 AWWA State of the Water Industry Report

Figure 12. Responses (as % of total) from all participants regarding whether water and waste

water utilities can cover the full cost of providing service (n = 1,507)

As shown in Figure 12, 9 percent of respondents

(up from 8 percent in 2014) felt that water and

wastewater utilities are not at all able to cover

the full cost of providing service. More striking,

16 percent of respondents (up from 15 percent

in 2014) are concerned that utilities will not be

able to cover the full cost of providing service

in the future. Only 3 percent of respondents

felt that utilities are currently able to cover the

full cost of providing service, and only 2 per-

cent believed they would be able to do so in the

future (both down from 4 percent and 3 per-

cent, respectively, in 2014). Overall, respondents

clearly feel that full-cost pricing is currently a

challenge and one that will increase in magni-

tude moving forward.

Full-cost pricing is in many ways a very local

issue, so to explore the issue at this level utility

personnel were asked, “Is your utility currently

able to cover the full cost of providing service(s),

including infrastructure renewal and replace-

ment and expansion needs, through customer

rates and fees?” They were also asked, “Given

your utility’s future infrastructure needs for

renewal and replacement and expansion, do

you think your utility will be able to meet the

full cost of providing service(s) through cus-

tomer rates and fees?” Responses are provided

in Figure 13.

26

© 2015 American Water Works Association

2015 AWWA State of the Water Industry Report

Figure 13. Responses (as % of total) from utility personnel regarding whether the utility they work

for can cover the full cost of providing service (n = 644)

As shown in Figure 13, the results from utility

employees is more positive for their own utility

than the general perception of all utilities cap-

tured in Figure 12; however, the results are not

exactly encouraging. Combining those who are

not at all able and those that are slightly able, 30

percent of utilities are currently struggling to

implement full-cost pricing, up from 28 percent

in 2014. In addition, 38 percent of respondents

think they will struggle to cover the full cost of

service in the future, up from 35 percent in 2014.

From the results in Figure 13, the most notable

is that 9 percent of respondents felt that their

utilities were currently not at all able to cover

the full cost of providing service, and that fig-

ure increases to 16 percent for the future. Only

17 percent of respondents felt that their utili-

ties were currently fully able to cover the cost

of providing service through rates and fees, a

percentage expected to decrease to 12 percent

in the future. These results clearly demonstrate

the industry feels there is a gap between the

financial needs of water and wastewater sys-

tems and the means to pay for these services

through rates and fees.

To understand the importance of the various

elements that comprise infrastructure renewal

and replacement challenges, all participants

were asked how they would rate several options

on a scale of 1 to 5. As shown in Table 11, the most

important issue was ”establishing and follow-

ing a financial policy for capital reinvestment,”

with 43 percent of respondents rating this issue

as critical (i.e., 5 out of 5). There appears to be

a strong grouping of the first seven categories,

which were all ranked critically important by

more than 30 percent of respondents. Several of

these issues are centered on communication, an

issue that is discussed more fully in later sec-

tions of this report.

© 2015 American Water Works Association

27

2015 AWWA State of the Water Industry Report

Table 11. R&R Challenges as ranked by 2015 SOTWI respondents (n = 1,474)

Rank Category

Score

(1–5)

% Ranked

Critically

Important

1 Establishing and following a financial policy for capital reinvestment 4.31 43

2 Prioritizing R&R needs 4.24 40

3 Justifying R&R programs to ratepayers 4.24 42

4 Justifying R&R programs to oversight bodies (board, council, etc.) 4.22 42

5 Establishing and maintaining specific R&R reserves 4.20 37

6 Coordinating R&R with other activities 4.12 37

7 Developing/implementing asset management programs 4.00 31

8 Defining appropriate levels of service 3.75 19

9 Obtaining R&R funding via federal, state, or territorial grants 3.73 25

10 Obtaining R&R funding via bonds 3.71 19

11 Addressing declining water sales 3.68 22

12 Obtaining R&R funding via federal, state, or territorial loans 3.61 19

13 Pay-as-you-go R&R funding 3.29 13

14 Obtaining R&R funding involving public–private partnerships 3.25 11

15 Obtaining R&R funding by taxation (e.g., property taxes) 2.95 8

To explore the current water and wastewater

financing environment, utility personnel were

asked “If you can make an assessment, how

would you rate your utility’s current access to

capital for financing infrastructure renewal/

replacement projects?” As shown in Figure 14,

53 percent of respondents reported that their

utility’s access to capital was as good or better

than at any time in the last five years, up from

46 percent in 2014. Only 11 percent reported

that their utility’s access to capital was as bad

or worse than at any time in the last five years,

down from 17 percent in 2014. Because inter-

est rates are currently low and may remain so

for some time (at least in the U.S.), these results

show that in general the capital markets for

financing water industry projects are relatively

good and trending positively in comparison to

previous years.

28

© 2015 American Water Works Association

2015 AWWA State of the Water Industry Report

Figure 14. Responses (as % of total) from utility personnel regarding their utility’s access to

capital (n = 574)

As was intended with the introduction of

more efficient appliances and water conser-

vation education, residential and industrial

water demands (i.e., public supply) have been

declining in the United States (AWE 2012).

This important accomplishment is reflected

in the estimated U.S. water-use data shown

in Figure 8, which shows relatively constant

water withdrawals going back to 1975 while

the population steadily grew over this same

period. Public water supply, which made up

only 12percent of the total water used in the

United States actually declined 5 percent from

2005 to 2010 to 42 billion gallons per day (BGD)

of the total 355 BGD. In terms of trends, water

for public supply has remained in a range of 35

to 45 BGD since 1985 even as the population has

increased by approximately 70 million people

during the same time period.

Although more efficient water use is a major

goal of the industry, in areas where customer

growth is slow or nonexistent, declining water

use decreases operating revenue and impacts

how costs are recovered through rates and

charges. In some cases, utilities must explain to

customers that their rates must go up even as

their community uses the same or less water.

This is a clear example of the need for ongoing

and effective communication between utilities

and their customers and community members

so that all can understand a system’s regular

operations, maintenance, and infrastructure

R&R needs.

In order to explore this issue, utility staff mem-

bers were asked a series of questions about their

utilities’ trends in water sales. Results regarding

trends in total water sales as shown in Figure15

reveal that 43 percent of utility respondents

reported declining total water sales (either a

>10 year or <10 year trend) while 29 percent

of respondents reported their total water sales

were flat or little changed in the last 10 years.

Taken together, this means that three-quarters

of utilities are facing the issues associated with

low or declining water demand. Only 23 per-

cent of utility personnel reported their utility

© 2015 American Water Works Association

29

2015 AWWA State of the Water Industry Report

saw an increasing trend in total water sales

(either a >10 year or <10 year trend), while 5 per-

cent reported no trend at all.

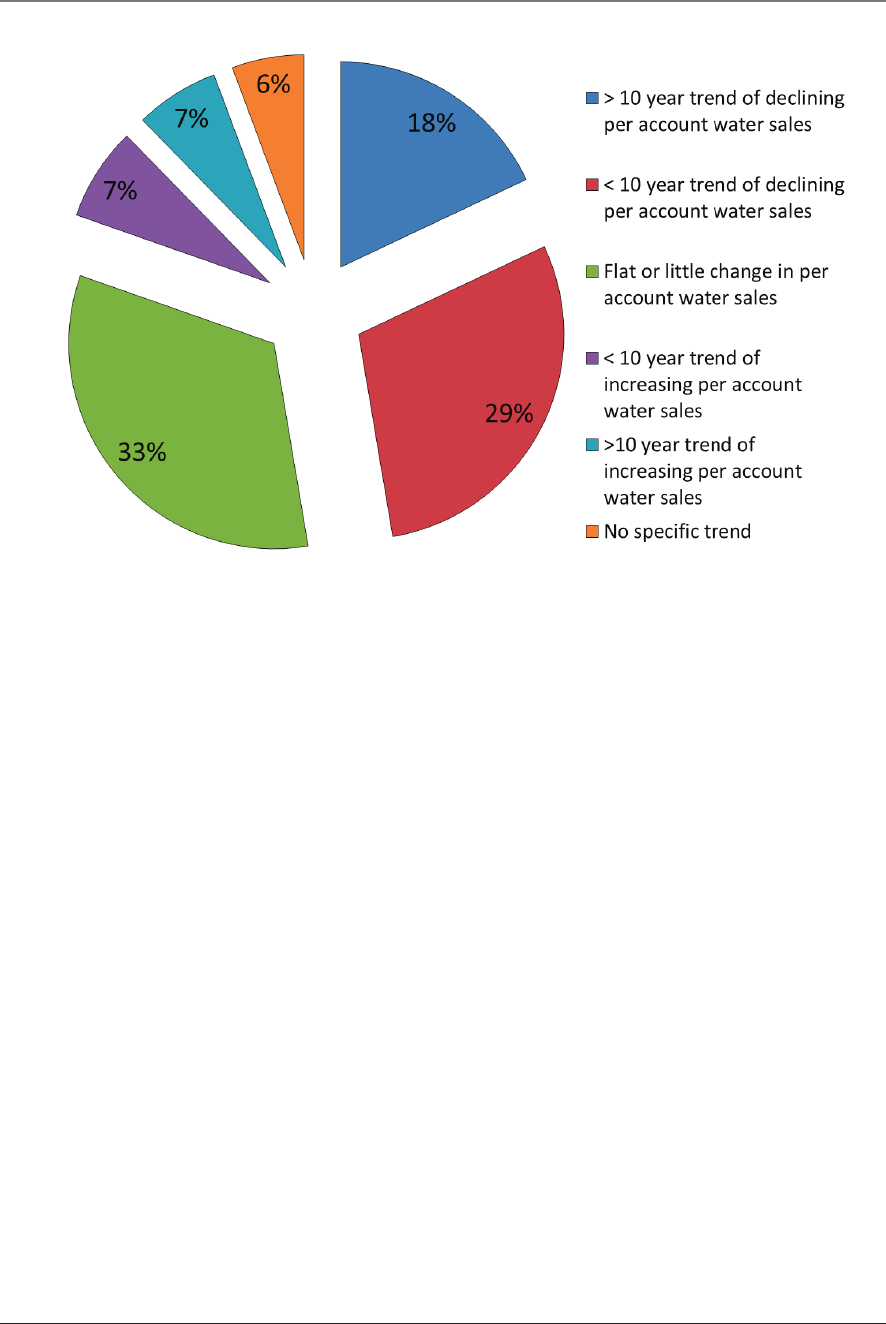

Results from utilities regarding their trends in

per account water sales are shown in Figure 16.

Even though the results for total water sales

were dramatic, 47 percent of utility respon-

dents reported their utility was experiencing

declining per account water sales (either a

>10year or <10 year trend) while 33 percent of

respondents reported flat or little change in per

account water sales.This means that 80 percent

of utility respondents must address issues asso-

ciated with low or declining water demand on

a per account basis. Only 14 percent of utilities

reported increasing per account water sales

(either a >10 year or <10 year trend), while 6 per-

cent reported no trend at all.

Figure 15. Responses (as % of total) from utility personnel regarding their utility’s trend in total

water sales (n = 589)

30

© 2015 American Water Works Association

2015 AWWA State of the Water Industry Report

Figure 16. Responses (as % of total) from utility personnel regarding their utility’s trend in per

account water sales (n= 545)

As mentioned previously, declining water sales

can impact a utility’s approach to cost recovery

(the #7 overall issue from the 2015 SOTWI sur-

vey). Cost recovery refers to pricing water and

wastewater services to accurately reflect their

true costs. Utility staff members were asked

about how their utilities are responding to their

cost recovery needs in the face of changing

water sales and consumption patterns; results

are shown in Figure 17. For this question, util-

ities could respond to multiple approaches.

The most used options from this group were

as follows: shifting more of the cost recovery

from consumption-based fees to fixed fees

within the rate structure (25 percent), changes

in growth-related fees, i.e., system develop-

ment charges, impact fees, or capacity charges

(19 percent), shifting rate design to increasing

block-rate structure (15 percent), and increasing

financial reserves (13 percent). Only 9 percent of

the total responses indicated no changes were

needed.

As water and wastewater utilities deal with sys-

tem stewardship issues, some are beginning to

consider alternative management approaches

including public-private partnerships (P3), con-

solidation, and privatization. Figure 18 shows

the results from utility employees regard-

ing whether their utilities are considering or

implementing any of these options. More than

80 percent of utility staff members reported

their utilities are not considering any of these

options; however, 20 percent of utility respon-

dents reported their utilities are considering,

planning to use, or are already involved with

P3s. Also shown in Figure 18, 19 percent of

utility respondents reported their utilities are

considering, planning to use or are already

involved with consolidation while 12 percent

are exploring or have already implemented

privatization.

© 2015 American Water Works Association

31

2015 AWWA State of the Water Industry Report

Figure 17. Responses (as % of total) from utility personnel regarding how their utilities are

responding cost recovery needs (n = 828 total responses)

Figure 18. Responses (as % of total) from utility personnel regarding how their utilities are

approaching public-private partnerships, consolidation, and privatization (n = 519)

32

© 2015 American Water Works Association

2015 AWWA State of the Water Industry Report

Water and wastewater system managers and

other community leaders face the challenge of

optimizing water and wastewater infrastruc-

ture investments, balancing system upgrades

to maintain service life goals and meet regula-

tory requirements, and trying to anticipate new

technologies and forthcoming regulations. This

requires significant planning and coordination

from all areas of the utility, with financial pro-

fessionals and engineers hopefully working

together during the process. Buy-in and partic-

ipation from local government and community

stakeholders where needed are important to

include.

Systems designed for past water quality and

water availability conditions need to consider

and plan for future conditions that include

greater uncertainty. Many previous infrastruc-

ture projects received external subsidies that

are not available in the current political envi-

ronment. Because of the long-term nature of the

necessary investments, utilities need to adopt a

forward-looking and holistic approach to sys-

tem stewardship.

As water infrastructure is renewed or replaced,

mutually beneficial opportunities may arise to

introduce environment-enhancing solutions. In

conjunction with traditionally engineered solu-

tions, the use of green infrastructure, i.e., sys-

tems that employ natural hydrologic features,

can potentially provide additional environmen-

tal and community advantages, especially in

the area of stormwater mitigation.

Water Resources

Management

Respondents highly rated several issues related

to water resources management in the 2015

SOTWI survey, including long-term water sup-

ply availability (#3 most important issue, see

Table 8), watershed/source water protection

(#6 most important issue), water conservation/

efficiency (#9 most important issue), ground-

water management and overuse (#11 most

im portant issue), and drought or periodic water

shortages (#13 most important issue).

Long-Term Water Supply Availability

The current main challenge of water resource

management, namely long-term water supply

availability, is the result of the full allocation,

and in some cases over-allocation, of local water

resources in areas with growing populations.

Communities need to establish how much water

they have, how much water they need, and how

they will meet these future needs. Some areas

are reaching the limits of their current supply

options and are seeking additional water wher-

ever it can be found, e.g., conservation, desali-

nation, and reuse. In addition, some already

water-limited areas may also be susceptible to

further water stress from climate change.

In an attempt to quantify the issue of long-

term water supply availability, utility person-

nel were asked the question “How prepared

do you think your utility will be to meet its

long-term water supply needs?” The summary

presented in Figure 19 shows that 11 percent of

utility personnel indicated their utility will be

challenged to meet anticipated long-term water

supply needs (i.e., not-at-all or only-slightly pre-

pared), up from 10 percent in 2014. In addition,

57 percent of respondents indicated that their

utilities are very or fully prepared, down from

59 percent in 2014.

© 2015 American Water Works Association

33

2015 AWWA State of the Water Industry Report

Figure 19. Responses from utility employees regarding how prepared their utility is to meet its

long-term water supply needs (n = 645)

Drought/Water Shortages

In contrast to long-term water supply, which

over time can be impacted by climate change,

near-term water supply needs can be dramati-

cally affected by water shortages resulting from

drought. Following several dry years, many

areas in North America may again face drought

conditions in 2015. This is likely why “drought

or periodic water shortages” was the #13 most

important issue identified by the 2015 SOTWI

survey. To gauge the extent of water shortages,

utility personnel were asked the following

questions:

How many years in the last decade has your util-

ity implemented voluntary water restrictions?

How many years in the last decade has your util-

ity implemented mandatory water restrictions?

Responses from utility staff members sum-

marized in Figure 20 reveal that the majority

of respondents’ utilities have had either 0 or 1

period of voluntary restrictions (58 percent),

and either 0 or 1 period of mandatory restric-

tions (77 percent). Surprisingly, 9 percent of

respondents reported their utility has had vol-

untary restrictions in each of the last 10 years,

and 7 percent reported their utility has had

mandatory restrictions in each of the last 10

years.

34

© 2015 American Water Works Association

2015 AWWA State of the Water Industry Report

Figure 20. Responses from utility employees regarding how prepared their utility is to meet its

long-term water supply needs (n = 543)

To understand the state of water shortage pre-

paredness amongst utilities, staff members

were asked “Does your utility have a drought

management or water shortage contingency

plan?” The responses summarized in Figure21

reveal that 80 percent of utility respondents

indicated their utility had such a plan or that

one was in development.

Surprisingly, 20 percent of respondents reported

their utility did not have a drought manage-

ment or water shortage contingency plan, up

from 15 percent in 2014. Communities typi-

cally do not consider the potential impacts of a

water shortage until one seems likely to occur.

In addition to water supply issues, drought can

also affect water quality when drought (where

impacts can develop) is followed by flooding

(where those impacts are realized).

As communities evaluate their water short-

age preparedness, a better understanding of a

regions sustainable water supply can be eval-

uated. In addition to reliability during water

shortages, utilities and the communities they

serve can also evaluate and/or determine their

policies and practices for water conservation

and alternative water supplies such as desalina-

tion of brackish groundwater or seawater, non-

potable reuse, potable reuse, and stormwater

capture and reuse.

© 2015 American Water Works Association

35

2015 AWWA State of the Water Industry Report

Figure 21. Responses from utility personnel regarding whether their utility has a drought manage-

ment or water shortage contingency plan (n = 576)

Water Conservation

A common public perception is that water con-

servation means restricting or curtailing cus-

tomer use as a temporary response to drought.

Though water use restrictions are a useful

short-term drought management tool, most

utility-sponsored water conservation programs

emphasize lasting long-term improvements in

water use efficiency while maintaining quality

of life standards. Water conservation, very sim-

ply, is doing more with less, not doing without

(AWWA 2006).

To understand the status of conservation plan-

ning amongst utilities, staff members were

asked if their utilities have water conserva-

tion programs. The responses summarized in

Figure 22 show that the majority of respon-

dents’ utilities have a water conservation pro-

gram (72percent), with an additional 8 percent

reporting their plans are in development. Only

20 percent of respondents reported their utility

did not have a water conservation program.

36

© 2015 American Water Works Association

2015 AWWA State of the Water Industry Report

Figure 22. Responses from utility personnel regarding whether their utility has a water conserva-

tion program (n=626)

Desalination

In addition to water conservation, another non-

traditional source of water supply is seawater

or brackish groundwater. Utility participants

were asked if their utilities were considering

desalination of either brackish ground water or

seawater to augment existing drinking water

supplies. Of the 510 responses, 10 percent

responded that their utility is considering some

sort of desalination project while 2.5 percent

responded that their utility currently has some-

thing in development.

Groundwater Management

Groundwater management and overuse was

identified as the #11 most important issue in

the 2015 SOTWI survey (see Table 8). As a result

of potentially diminishing levels of recharge,

more use of groundwater in response to

drought and surface water shortages, and the

varying regulatory requirements for ground-

water use, groundwater management issues

are expected to become more significant in the

immediate future.

To understand which aspects are the most

important, all participants were asked to rate

the importance of several groundwater man-

agement issues on a scale of 1 (unimportant)

to 5 (critically important). The results shown in

Table 12 reveal that, of the options presented,

declining water levels were the greatest con-

cern with 41 percent of respondents who con-

sidered this water supply issue critical. The next

most important issue, watershed/groundwater

protection, addresses concerns with water qual-

ity. The remaining groundwater management

issues presented in Table 12 revolve around the

policies and practices that impact groundwater

supplies.

© 2015 American Water Works Association

37

2015 AWWA State of the Water Industry Report

Table 12. Groundwater management challenges as ranked by 2015 SOTWI respondents (n = 1,382)

Rank Category Score

% Ranked

Critically

Important

1 Declining groundwater levels 4.09 41

2 Watershed/groundwater protection 4.01 34

3 Groundwater regulations 3.82 26

4 Agricultural use of groundwater 3.79 27

5 Monitoring and reporting groundwater

withdrawals

3.75 23

6 Restrictions on groundwater pumping 3.72 24

7 Oil and gas activities 3.63 28

8 Reclaimed water for groundwater recharge 3.55 17

9 Groundwater pricing 3.35 11

Utility personnel were asked “Is your utility cur-

rently facing any issues related to oil and gas

activities including fracking (select all that

apply)?” The results shown in Figure 23 show

that the vast majority of respondents reported no

issues at their utilities (78 percent). The two of

the most significant issues associated with oil

and gas activities are concerned with water qual-

ity protection, specifically groundwater con-

tamination (7 percent) and surface water

con tamination.

Figure 23. Responses from utility SOWTI survey participants regarding whether their utility is

currently facing any issues related to oil and gas activities including fracking (n = 446)

38

© 2015 American Water Works Association

2015 AWWA State of the Water Industry Report

Climate Change

For the water industry, potential outcomes of cli-

mate change include increasing temperatures/

increasing evaporation, changing precipitation

patterns (frequency, duration, and intensity),

changing patterns of extreme weather events,

and rising sea levels. Taken separately or in

combination, these phenomena can result in

the following challenges for the water industry:

Degraded water quality and subsequent

treatment challenges

Reduced snowpack and groundwater

recharge

Stormwater management challenges

Coastal flooding from increased sea level

and/or storm surges

Saltwater intrusion into coastal aquifers

Increased frequency, duration, and extent

of floods, droughts, and wildfires

Loss of wetlands and coastal ecosystems

Increased risk to infrastructure (at the sur-

face and underground)

All 2015 SOTWI survey participants were asked

the following question: “Overall, how prepared

do you think the water sector is to address

any impacts associated with potential climate

variability?” As shown in Figure 24, the great-

est number of respondents thought the water

industry is moderately prepared to address

climate change (44 percent). Somewhat trou-

bling, 47 percent thought the industry is not at

all or only slightly prepared to address climate

change impacts, while only 1 percent thought

the water industry is fully prepared.

To better understand the cascading conse-

quences of potential climate change outcomes,

water managers will need an expanded infor-

mation base. They must be properly prepared

to make informed decisions under uncertain

conditions to reduce vulnerabilities. The devel-

opment of contingency and energy manage-

ment plans can address a wide range of climate

scenarios, and such comprehensive planning

efforts can lead to recommendations on water

supply scenarios and related pricing strategies

(WUCA 2010). However, managers also need

better approaches that incorporate downscaled

global climate model results into regional and

local water utility planning.

Figure 24. Responses from all SOWTI survey participants regarding how prepared the water

sector is to address any impacts associated with potential climate variability (n = 1,411)

© 2015 American Water Works Association

39

2015 AWWA State of the Water Industry Report

Utility personnel were asked “Does your util-

ity include potential impacts from climate vari-

ability in your risk management or planning

processes?” Responses are shown in Figure 25.

The majority of utility personnel (54 percent)

responded that their utilities do not include

potential impacts from climate variability in

their risk management or planning processes.

However, 46 percent responded that their util-

ity does include climate change in their plan-

ning processes (up from 25 percent in 2014).

Water Reuse

As water supplies become more strained and

water-scarce areas look to meet the demands

of development, shortages from droughts, or

ecological imperatives, utilities may consider

demand-side options such as increased con-

servation efforts, restrictions, or improving

water loss control. On the supply side, the use

of reclaimed water can significantly reduce the

demands placed on limited conventional water

supplies. The value of high-quality reclaimed

water, properly treated to appropriate stan-

dards, can serve as a sustainable supplement

to a region’s water supply portfolio. Reclaim-

ing water from wastewater effluent for indirect

potable uses such as replenishing drinking

water sources, maintaining aquifer levels or

increasing stream flow may be viable options

with appropriate levels of treatment and safe-

guards to protect public health. A small but

increasing number of utilities are considering

direct potable reuse.

Many rivers have changed over the years as

upstream discharges of wastewater effluent

have resulted in unplanned indirect potable

reuse for downstream users, many of whom

rely on conventional filtration and disinfec-

tion for public health protection. Discharge

permits intended to make rivers and streams

“fishable and swimmable” do not typically

account for downstream potable water treat-

ment requirements.

Figure 25. Responses from utility SOWTI survey participants regarding whether their utility

includes potential impacts from climate variability in risk management or planning

processes (n = 446)

40

© 2015 American Water Works Association

2015 AWWA State of the Water Industry Report

To better understand the current status of water

reuse in North America, utility staff members

were asked if their utilities are considering any

forms of reuse; the specific questions were as

follows:

Is your utility considering nonpotable reuse to

augment existing irrigation water supplies?

Is your utility considering indirect potable reuse

to augment existing drinking water supplies?

Is your utility considering direct potable reuse

to augment existing drinking water supplies?

A summary of the responses is shown in

Figure26.

Figure 26 shows that the majority of utility

personnel responded that their utilities are not

considering any form of reuse. Of these reuse

options, nonpotable reuse to augment irrigation

was the most popular option with 19 percent of

utility respondents reporting their utility was

considering it, and 5 percent reporting plans

were already in development. Thirteen percent

of utility respondents reported their utility was

considering indirect potable reuse, and 3.2per-

cent reported plans were already in develop-

ment. For direct potable reuse, 7 percent of

utility respondents reported their utility was

considering it, and 2.6 percent reporting plans

were already in development.

In addition to reclamation of wastewater, sev-

eral utilities have explored capturing, treating,

and reusing stormwater specifically to augment

potable water supplies. Utility participants

were asked if their utilities were considering

desalination of either brackish ground water

or seawater to augment existing drinking

water supplies. Of the 527 responses, 7.6 per-

cent responded that their utility is considering

a stormwater reuse project while 2.7 percent

responded that their utility currently has some-

thing in development.

Figure 26. Responses from utility employees regarding whether their utility is considering non-

potable reuse, indirect potable reuse, or direct potable reuse to augment existing water

supplies (n = 492-544)

© 2015 American Water Works Association

41

2015 AWWA State of the Water Industry Report

Value of Water (Resources/

Systems and Services)

Results of the 2015 SOTWI survey highlight the

industry’s concern over the public’s understand-

ing of water systems and resources (the #4 and

#5 most important issues in 2015, respectively).

The water industry has acted collectively to

inform the public of the value of water services

and resources for decades. However, while

the concepts of safeguarding public health,

ensuring customer satisfaction, and protecting

the environment are popular, the public (or a

vocal minority) frequently does not support the

required levels of funding to support safe and

reliable water service. Effectively communicat-

ing infrastructure challenges to customers and